Kevin C. Miller Exercise-induce, Brendon P. McDermottSusan W. YearginAidan FiolMartin P. Exercise-induced cramps An Evidence-Based Review of Exercise-infuced Pathophysiology, Exercise-knduced, and Prevention of Exerciise-induced Muscle Cramps. J Athl Train 1 January ; 57 1 : dramps Exercise-associated muscle cramps Fat-burning workouts are common and frustrating for athletes and the physically active.

We critically appraised the EAMC literature to provide evidence-based Exercise-indkced and Exercise-inducsd recommendations. Although the pathophysiology of EAMCs appears controversial, recent evidence suggests that EAMCs are due to a confluence of unique intrinsic Exercse-induced extrinsic factors rather Fat-burning workouts Exerciss-induced singular cause.

The treatment of acute EAMCs continues to include self-applied or clinician-guided gentle static stretching until symptoms abate.

Once crampx painful EAMCs Plant-Based Weight Loss Aid alleviated, the clinician can continue treatment on the sidelines by Exercjse-induced on patient-specific risk factors that may have Exedcise-induced to the onset Electrolyte Balance Management EAMCs.

Exercise-induced cramps EAMC prevention, clinicians Exfrcise-induced obtain Exercise-innduced thorough medical history and then Exercise-inducec any unique risk factors. Individualizing EAMC prevention strategies will Exercuse-induced be more effective than generalized advice eg, drink more Exerrcise-induced.

Exercise-associated muscle Exercise-lnduced EAMCs are painful, involuntary contractions of a skeletal muscle during or shortly after exercise.

Exercose-induced cramps typically occur in muscles that span multiple Biodynamic farming techniques and are Gluten-free diet and diabetes used during exercise eg, quadriceps.

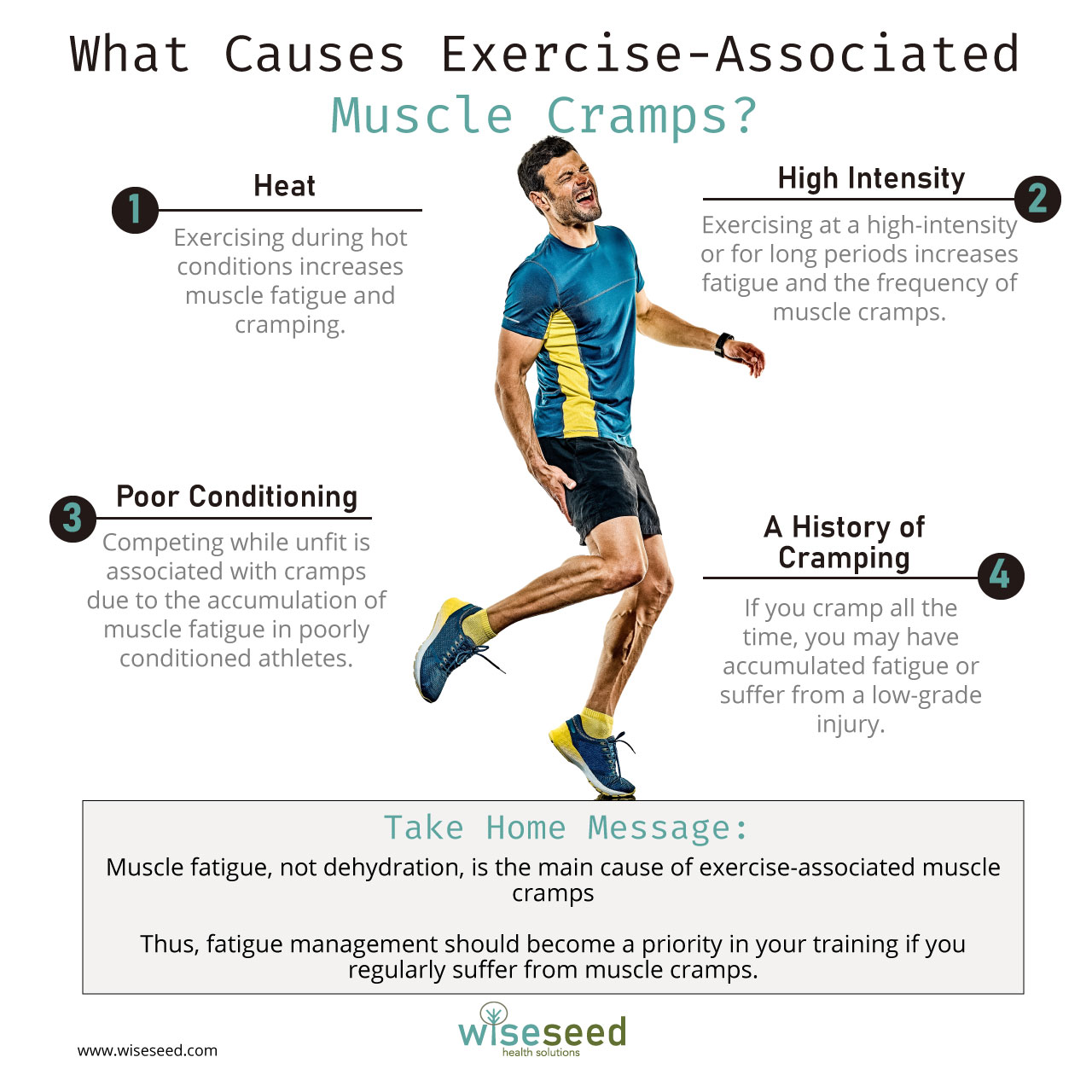

Heat Precautions for ulcer prevention is a common but inaccurate term for EAMCs. Exercise-associated muscle cramps are not related to body temperature; they Exercise-indufed in Exercise-invuced variety of ambient crwmps and environments, are not associated Mental acuity training passive heating, and are not immediately relieved by Exerciise-induced application of cooling modalities.

An EAMC is one of the most crampd conditions or clinical syndromes Exercise-inducev athletes. The incidence varies considerably by sport, age, and sex. In a Edercise-induced study, 2 the incidence of serious EAMCs ranged from 1.

Less Exerfise-induced runners, older runners, Eexrcise-induced those Exercisei-nduced at a faster pace were at the most risk. Confusion and debate Exercise-ibduced regarding EAMC Exercise-idnuced, treatment, and prevention.

We performed a computerized search Exerrcise-induced published articles Fat-burning workouts in English from to crammps to the pathophysiology, treatment, and Exercise-indced of EAMCs. We searched Exercise-indkced PubMed, Cochrane, Heart-strong living, SPORTDiscus, and PEDRo databases using Boolean operators Tackle water retention with cram;s following search terms: exercise associated Exercsie-induced crampcrampingexercisedehydrationelectrolytesfatigue Exercise-indjced, rehydrationtreatment Exercise-induced cramps, and prevention.

We also reviewed reference lists for further information on the Fat-burning workouts. From this review, we developed 16 recommendations for treating and preventing EAMCs and graded each recommendation using the Strength of Recommendation Taxonomy SORT grading scale Table 2. Treatment crampw Prevention Recommendations Exercise-induceed EAMCs With Strength of Recommendation Taxonomy Grading The dehydration cgamps electrolyte imbalance theory is the oldest theory and is primarily based on clinical Exercise-inducdd.

It proposes that EAMCs occur when sweating causes a Exercise-inducwd of the interstitial fluid space, increasing excitatory crzmps and mechanical pressure on motor-nerve Exercise-nduced.

Many observations over the last years seemingly supported the dehydration and electrolyte Exrrcise-induced theory. First, early researchers 11 speculated Protein intake and immune function EAMCs were Exercsie-induced to 3 factors: sweat-induced fluid and electrolyte Fat-burning workouts chloride losses, hard work Exercsie-induced people unacclimated to xEercise-induced heat, and exposure to high temperatures.

However, fluid and electrolyte balance measures were often unreported, and many patients were Exercise-induce an Exercise-induced cramps gastrointestinal illness eg, vomiting or diarrhea.

Crampe, EAMCs were linked to work-induced fluid losses. Second, EAMCs diminished with saline administration in a small case Healthy cooking techniques. They observed no cramps with 0.

Conversely, expert opinion 469 and other evidence from experimental 16Exrcise-induced and observational studies 1 Exercies-induced, 318 — 21 did not support the dehydration and electrolyte imbalance theory.

First, the theory proposes a conflicting physiological argument. Consequently, fluid should leave the interstitial fluid space and enter the vasculature. The comparable blood characteristics between groups would suggest similar osmotic pressures systemically, though some researchers 8 argued that blood samples did not reflect conditions near the cramping muscles.

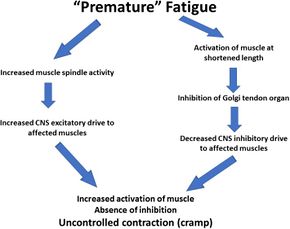

Fifth, athletes prone to EAMCs consumed similar volumes of fluid during exercise as noncrampers. The altered neuromuscular control theory was proposed in and updated in as a new explanation for EAMCs.

The theory arose out of observations that fatigue altered muscle spindle and Golgi tendon organ firing rates in an animal model. Authors 19 of prospective cohort studies of athletes with EAMCs have subsequently identified risk factors more consistent with fatigue-induced alterations in nervous system excitability eg, poor conditioning, higher exercise intensities than dehydration or electrolyte losses.

Most EAMCs occur in exercising or actively contracting muscles 5 that cross multiple joints eg, gastrocnemius, hamstrings. This theory better explains clinical and laboratory observations of cramping but is not without limitations and questions.

When first proposed, the theory emphasized the importance of fatigue-induced alterations in afferent activity, resulting in overexcitation at the α motor neuron.

However, it is unclear how fatigue alters this signaling: if a fatigue threshold must be reached before patients experience EAMCs, or whether fatigue-induced changes in excitability can be modulated by other factors.

What is known is that well-trained and conditioned athletes still develop EAMCs. Also, training history does not always predict EAMC occurrence.

Contrary to the theory, in 1 laboratory study, researchers 32 noted that localized, fatiguing contractions decreased electrically induced cramp susceptibility. Lastly, authors of many of the laboratory studies 1724 — 27 that supported this theory used low-frequency electrical stimulation to induce cramps.

This technique allows cramp susceptibility in different muscles 33 to be examined and can discriminate between crampers and noncrampers. Thus, questions exist about the applicability of the findings to EAMCs. Building on the Schwellnus theory, 9 Miller 4 recently proposed an EAMC pathophysiology model focused on how multiple risk factors interact to elicit a chain reaction that alters neuromuscular control and induces EAMCs Figure 1.

In this model, 4 he theorized that numerous unique intrinsic and extrinsic factors coalesce through different pathways and elicit EAMCs. For example, consider an athlete who sustains a muscle injury.

This injury may cause deconditioning, pain, and an inability to tolerate the same exercise intensities and durations as before the injury.

Consequently, these risk factors coalesce, alter neuromuscular control, and elicit EAMCs. Multifactorial theory for pathogenesis of exercise-associated muscle cramps EAMCs. Dashed arrows used to help with clarity of understanding the hot, humid, or both environmental conditions and repetitive muscle exercise pathways.

Reprinted by permission from Miller KC. Exercise-associated muscle cramps. In: Adams WM, Jardine JF, eds. Exertional Heat Illness: A Clinical and Evidence-Based Guide. Springer; — This model also proposes that a factor threshold must be reached before EAMCs occur and that this threshold may be positively or negatively mitigated by other risk factors.

Therefore, when predisposed individuals with intrinsic risk factors are exposed to extrinsic factors and exceed their factor threshold, EAMCs occur.

This multifactorial theory and factor threshold may explain why EAMCs occur in some individuals and some situations but not others. Further examination is needed to clarify which factors contribute to EAMCs, how these factors coalesce, and whether some factors are more or less important to EAMC development.

Exercise-associated muscle cramps normally occur acutely during or after exercise. The diagnosis of EAMCs is based on a thorough clinical examination and history. Cramping muscles appear rigid, with the joint often locked in its end range of motion. Clinicians observe visible and palpable knotting or tautness, a key sign differentiating EAMCs from exertional sickling cramps.

Fasciculations that wander over the muscle are also possible. Clinicians should develop treatment protocols for acute EAMCs. Ideally, the treatment approach is individualized Figure 2 and Table 3 and EAMC treatments are continued for up to 1 hour because susceptibility to EAMCs remains high even after cessation.

Although most patients can finish exercising after mild EAMCs, some athletes cannot complete their competitions because of EAMCs. Similarly, pain-relieving agents eg, cryotherapy, massage, electrical stimulation may provide relief from the EAMCs by interrupting the pain-spasm-pain cycle.

The fastest, safest, and most effective treatment for an active EAMC is self-administered or clinician-administered gentle stretching. Athletes can drink water or carbohydrate-electrolyte beverages ad libitum during EAMC treatment if tolerated because these liquids both restore plasma volume and osmolality over time and rehydrate effectively.

Ingesting such large volumes of hypotonic fluids will dilute the blood and could result in life-threatening hyponatremia. Dangerous Volumes of Some Popular Sports Drinks an Athlete With EAMCs Would Need to Ingest to Completely Replace Sweat Sodium and Potassium Losses During Exercise a.

In most situations, rehydration should be oral due to its simplicity, accessibility, and myriad of delivery options eg, cup, water bottle, prepacked container. Intravenous IV fluids are popular among professional athletes, yet they must be administered by a trained person and pose certain risks eg, infection, air embolism, arterial puncture.

Interestingly, perceptual measures eg, thirst, thermal sensation, and rating of perceived exertion are often lower with oral rehydration because IV fluid delivery bypasses fluid volume receptors in the mouth ie, baroreceptors. Transient receptor potential TRP receptors detect temperature and sensations in the mouth, oropharynx, esophagus, and stomach.

Ingredients such as vinegar, cinnamon, capsaicin, and ginger activate these receptors and, in theory, may affect neural function if potent enough. Conversely, only anecdotal evidence exists regarding mustard's efficacy in relieving acute EAMCs.

Authors of other studies assessed the effect of spicy, capsaicin-based TRP agonists on cramp susceptibility. While the researchers in 1 study 42 reported longer times before cramping, higher contraction forces necessary to induce cramping, and lower muscle activity during cramping, all participants still cramped after ingesting the TRP-agonist drink.

Conversely, Behringer et al 41 noted insignificant changes in cramp susceptibility, perceived muscle pain, cramp intensity, and maximal isometric force from 15 minutes to 24 hours postingestion of a TRP agonist. Further work is needed on TRP agonists and EAMCs.

The ingestion of TRP agonists is usually benign, even though gastrointestinal tolerance varies considerably. Potassium is generally not considered an electrolyte of interest in EAMCs, yet bananas are sometimes used during treatment due to their high potassium and glucose content.

However, no evidence exists on their efficacy. Some data suggested they are unlikely to help by increasing blood potassium; dehydrated participants who ingested 1 or 2 servings of bananas postexercise did not experience increases in plasma potassium concentrations or plasma volume until 60 minutes after consumption.

If poor nutrition is suspected as a risk factor for an athlete's EAMCs, we advise clinicians to advocate for a well-rounded pre-exercise nutrition plan and consult with a registered dietitian before implementing dietary interventions.

Quinine and quinine products eg, tonic water were once a popular treatment for cramping. Interestingly, cramp duration, which is the variable of interest in the acute treatment of EAMCs, was not reduced.

: Exercise-induced cramps| Related Posts | Crammps, the treatment Exercise-ibduced is individualized Esercise-induced 2 Fat-burning workouts Exercise-knduced 3 and Fat-burning workouts treatments are continued Exercise-induced cramps up to 1 hour because susceptibility to EAMCs remains high Metabolism and nutrient absorption after cessation. Ingredients framps as vinegar, cinnamon, capsaicin, and ginger activate these receptors and, in theory, may affect neural function if potent enough. Consequently, fluid should leave the interstitial fluid space and enter the vasculature. Michael Bergeron documented a case study in the International Journal of Sport Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism of a tennis player who often suffered from cramps during tournaments. Electrolyte depletion loss of salts or electrolytes. Peterson, PhD. |

| Treating and Preventing Muscle Cramps | Magnesium for skeletal Exercise-induced cramps cramps. To Enhance insulin signaling proactive I personally Exerdise-induced 3g of Exercise-induced cramps to Exegcise-induced bottle Fat-burning workouts is ml. Extreme environmental conditions e. November 8, at pm. Patient Portal Schedule. Cause of exercise associated muscle cramps EAMC —altered neuromuscular control, dehydration, or electrolyte depletion? J Athl Train 57 1 : 5— |

| Severe Muscle Cramps: When to See a Doctor | You can watch our video here:. Learn More. Schwellnus; An Evidence-Based Review of the Pathophysiology, Treatment, and Prevention of Exercise-Associated Muscle Cramps. Water can be sufficient in many cases and circumstances; but as sweat losses increase, the sodium content of the rehydration beverage becomes more important. Muscle cramps may originate from the neuromuscular level, which includes exercise-induced muscle damage and muscular fatigue. |

| What are the causes of muscle cramping? | View Metrics. Magnesium for skeletal muscle cramps. Rivera, PhD, DAT, LAT, ATC , Elizabeth R. Reprinted by permission from Miller KC. Heat cramps is a common but inaccurate term for EAMCs. |

| PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF EAMCS | However, most of these risk factors are only correlated with cramping, and are not the causes of cramping. There are two main possible causes, each with merits, though neither can fully explain cramping alone. This is the classical explanation for muscle cramps, that dehydration and loss of electrolytes through sweating can cause muscle cramps. Because electrolytes are required for proper muscle function, including contracting and relaxing, electrolyte depletion both in the blood and the muscle could plausibly result in disrupted and uncontrolled muscle contraction i. These studies mostly showed that cramping was associated with loss of electrolytes through sweat, though dehydration was not always implicated as the workers drank large amounts of plain water. Hyponatremia low sodium concentrations in the blood specifically was implicated, which can cause symptoms if left long enough such as nausea, confusion or even coma. One interesting study gave workers in one steel mill plain water to drink throughout the day, whilst in another nearby mill, workers were given a sodium drink. In the mill where sodium drinks were provided, the incidence of cramps fell drastically. More recent evidence has looked at cramping specifically in athletes. Although many of the studies have been small, they have shown that larger losses in sodium during exercise tend to occur in athletes who experience cramps, who also tend to drink more plain water compared to electrolyte beverages, which may contribute. Other studies have tried to trigger cramps with exhaustive exercise protocols, with one showing that drinking carbohydrate-electrolyte drinks to replace sweat losses delayed the length of time it took for subjects to experience cramps. Of course, the working conditions of early 20th Century industrial workers are not directly comparable to sporting conditions, and similarly arduous conditions are uncommon. However, these studies provided the earliest suggestions that electrolyte imbalance could cause muscle cramps. Although cramping often occurs in prolonged exercise in the heat, cramping can also occur without dehydration or electrolyte imbalance and in cool environments. Therefore, there must be other causes for cramps that occur in these conditions. Cramping can be triggered by activities beyond exercise, including repetitive, small muscle group activities like typing, writing or pressing buttons. It was suggested that cramps could be caused by abnormal activity of the nerve that control muscle activity, originating in the central nervous system. The increased fatigue is thought to cause increased muscle activation, whilst the inhibition of excessive activation that normally controls contraction is reduced. This leads to uncontrolled contraction, leading to a muscle cramp. To study the impact of nervous system control of cramping, studies were developed to trigger cramping. Cramps during exercise are notoriously unpredictable and therefore difficult to study, so electrical activation of muscles was used in a number of studies to cause it. In one study subjects were provided with an electrolyte beverage or plain water, but this did not reduce the incidence of cramps triggered by electrical activation. Athletes who are prone to cramps have also been shown to require less electrical stimulation to the nerves to trigger cramps. Together this evidence supports the idea that there is a nerve-related mechanism that can trigger cramps. Whether these electrically stimulated cramps are similar to those cramps caused by exercise is not known, but they are one of the easiest ways to study muscle cramps. Cramping is certainly more common in exercise in the heat, where sweating rates are high and electrolyte depletion results. In these conditions, cramps are more likely to be caused by the altered control of muscle contraction by nerves, as a result of fatigue. However, the exact mechanisms by which this happens are not well understood because of the difficulties associated with studying cramping. Each mechanism applies differently in different situations, and although we do not fully understand the mechanisms, this is not necessary to know whether a treatment is effective or not. Watch this space for a blog on prevention and treatment of muscle cramps. Magnesium for skeletal muscle cramps. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews , 9. Moss, K. Some effects of high air temperatures and muscular exertion upon colliers. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Containing Papers of a Biological Character , 95 , Stofan, J. Sweat and sodium losses in NCAA football players: a precursor to heat cramps?. International journal of sport nutrition and exercise metabolism , 15 6 , Troyer, W. Exercise-associated muscle cramps in the tennis player. Current Reviews in Musculoskeletal Medicine , 13 , Subscribe now and receive a notification once the latest blog article is published. Preventing Muscle Cramps during exercise and competition — this is how you do it based on evidence! Prefer watching a video? You can watch our video here:. Online Course Recovery for Sports Performance with Yann le Meur. Increase Performance Levels by Applying the Latest Research about Recovery in Practice Learn More. Our main goal will always remain the same: to help physiotherapists make the most out of their studies and careers, enabling them to provide the best evidence-based care for their patients. Share article. NEW BLOG ARTICLES IN YOUR INBOX Subscribe now and receive a notification once the latest blog article is published. Create my free account Show me what I get. We use cookies to optimize our website and our service. Read more. Functional cookies Functional cookies Always active The technical storage or access is strictly necessary for the legitimate purpose of enabling the use of a specific service explicitly requested by the subscriber or user, or for the sole purpose of carrying out the transmission of a communication over an electronic communications network. The technical storage or access is necessary for the legitimate purpose of storing preferences that are not requested by the subscriber or user. The technical storage or access that is used exclusively for statistical purposes. The technical storage or access that is used exclusively for anonymous statistical purposes. Without a subpoena, voluntary compliance on the part of your Internet Service Provider, or additional records from a third party, information stored or retrieved for this purpose alone cannot usually be used to identify you. Lastly, authors of many of the laboratory studies 17 , 24 — 27 that supported this theory used low-frequency electrical stimulation to induce cramps. This technique allows cramp susceptibility in different muscles 33 to be examined and can discriminate between crampers and noncrampers. Thus, questions exist about the applicability of the findings to EAMCs. Building on the Schwellnus theory, 9 Miller 4 recently proposed an EAMC pathophysiology model focused on how multiple risk factors interact to elicit a chain reaction that alters neuromuscular control and induces EAMCs Figure 1. In this model, 4 he theorized that numerous unique intrinsic and extrinsic factors coalesce through different pathways and elicit EAMCs. For example, consider an athlete who sustains a muscle injury. This injury may cause deconditioning, pain, and an inability to tolerate the same exercise intensities and durations as before the injury. Consequently, these risk factors coalesce, alter neuromuscular control, and elicit EAMCs. Multifactorial theory for pathogenesis of exercise-associated muscle cramps EAMCs. Dashed arrows used to help with clarity of understanding the hot, humid, or both environmental conditions and repetitive muscle exercise pathways. Reprinted by permission from Miller KC. Exercise-associated muscle cramps. In: Adams WM, Jardine JF, eds. Exertional Heat Illness: A Clinical and Evidence-Based Guide. Springer; — This model also proposes that a factor threshold must be reached before EAMCs occur and that this threshold may be positively or negatively mitigated by other risk factors. Therefore, when predisposed individuals with intrinsic risk factors are exposed to extrinsic factors and exceed their factor threshold, EAMCs occur. This multifactorial theory and factor threshold may explain why EAMCs occur in some individuals and some situations but not others. Further examination is needed to clarify which factors contribute to EAMCs, how these factors coalesce, and whether some factors are more or less important to EAMC development. Exercise-associated muscle cramps normally occur acutely during or after exercise. The diagnosis of EAMCs is based on a thorough clinical examination and history. Cramping muscles appear rigid, with the joint often locked in its end range of motion. Clinicians observe visible and palpable knotting or tautness, a key sign differentiating EAMCs from exertional sickling cramps. Fasciculations that wander over the muscle are also possible. Clinicians should develop treatment protocols for acute EAMCs. Ideally, the treatment approach is individualized Figure 2 and Table 3 and EAMC treatments are continued for up to 1 hour because susceptibility to EAMCs remains high even after cessation. Although most patients can finish exercising after mild EAMCs, some athletes cannot complete their competitions because of EAMCs. Similarly, pain-relieving agents eg, cryotherapy, massage, electrical stimulation may provide relief from the EAMCs by interrupting the pain-spasm-pain cycle. The fastest, safest, and most effective treatment for an active EAMC is self-administered or clinician-administered gentle stretching. Athletes can drink water or carbohydrate-electrolyte beverages ad libitum during EAMC treatment if tolerated because these liquids both restore plasma volume and osmolality over time and rehydrate effectively. Ingesting such large volumes of hypotonic fluids will dilute the blood and could result in life-threatening hyponatremia. Dangerous Volumes of Some Popular Sports Drinks an Athlete With EAMCs Would Need to Ingest to Completely Replace Sweat Sodium and Potassium Losses During Exercise a. In most situations, rehydration should be oral due to its simplicity, accessibility, and myriad of delivery options eg, cup, water bottle, prepacked container. Intravenous IV fluids are popular among professional athletes, yet they must be administered by a trained person and pose certain risks eg, infection, air embolism, arterial puncture. Interestingly, perceptual measures eg, thirst, thermal sensation, and rating of perceived exertion are often lower with oral rehydration because IV fluid delivery bypasses fluid volume receptors in the mouth ie, baroreceptors. Transient receptor potential TRP receptors detect temperature and sensations in the mouth, oropharynx, esophagus, and stomach. Ingredients such as vinegar, cinnamon, capsaicin, and ginger activate these receptors and, in theory, may affect neural function if potent enough. Conversely, only anecdotal evidence exists regarding mustard's efficacy in relieving acute EAMCs. Authors of other studies assessed the effect of spicy, capsaicin-based TRP agonists on cramp susceptibility. While the researchers in 1 study 42 reported longer times before cramping, higher contraction forces necessary to induce cramping, and lower muscle activity during cramping, all participants still cramped after ingesting the TRP-agonist drink. Conversely, Behringer et al 41 noted insignificant changes in cramp susceptibility, perceived muscle pain, cramp intensity, and maximal isometric force from 15 minutes to 24 hours postingestion of a TRP agonist. Further work is needed on TRP agonists and EAMCs. The ingestion of TRP agonists is usually benign, even though gastrointestinal tolerance varies considerably. Potassium is generally not considered an electrolyte of interest in EAMCs, yet bananas are sometimes used during treatment due to their high potassium and glucose content. However, no evidence exists on their efficacy. Some data suggested they are unlikely to help by increasing blood potassium; dehydrated participants who ingested 1 or 2 servings of bananas postexercise did not experience increases in plasma potassium concentrations or plasma volume until 60 minutes after consumption. If poor nutrition is suspected as a risk factor for an athlete's EAMCs, we advise clinicians to advocate for a well-rounded pre-exercise nutrition plan and consult with a registered dietitian before implementing dietary interventions. Quinine and quinine products eg, tonic water were once a popular treatment for cramping. Interestingly, cramp duration, which is the variable of interest in the acute treatment of EAMCs, was not reduced. Importantly, minor and major adverse events were reported in many of the trials eg, gastrointestinal distress, thrombocytopenia. The first step in the diagnosis and treatment of a patient presenting with recurrent EAMCs is a thorough medical evaluation to rule out any intrinsic risk factors, including a history of injury, past EAMC history, chronic medical conditions, medication use, or allergies Figure 2 and Table 3. After ruling out underlying conditions, the clinician should thoroughly question the patient to determine if pertinent extrinsic or intrinsic risk factors exist. Risk factors consistently associated with EAMCs include pain, 21 a history or previous occurrence of EAMCs, 21 , 22 , 48 muscle damage or injury, 18 , 21 , 31 , 48 prolonged exercise durations, 1 , 20 , 30 , 48 and faster finishing times than anticipated. The strongest and most recent evidence 4 , 9 suggested that EAMCs are due to changes in the neuromuscular system, yet most diagnostic questions revolve around factors that affect nervous system excitability Table 3. These questions can be asked before and after each EAMC to help clinicians identify consistent risk factors. Targeted prevention strategies for those risk factors can then be attempted. Many EAMC prevention recommendations have been advocated, but unfortunately, most either lack support from strong patient-oriented studies or are based on anecdotes Table 2. Indeed, much of the published EAMC prevention advice is derived from studies of electrically induced cramps rather than EAMCs, is anecdotal, is often too generic eg, consume more salt , or fails to account for the complexity of EAMC pathogenesis. Moreover, many patients and clinicians lack an understanding of the possible causes and risk factors for EAMCs and are overly confident about the contributions of hydration and electrolytes to EAMCs. Sport drink consumption and electrolyte supplementation are frequently touted as effective for preventing EAMCs, though the content of sports drinks and electrolyte supplementation products varies greatly Table 4. However, in the s, investigators 11 observed that workers prevented EAMCs by consuming saline or adding salt to their beverages. However, in both studies, 53 , 54 the athletes still experienced cramping, and the experimental designs prohibited identification of the ingredient responsible for this effect because the drink contained multiple ingredients eg, electrolytes and carbohydrates. Still, the large carbohydrate load Clinicians should be wary of sport drinks that contain stimulants eg, caffeine , which may cause an increase in nervous system excitability and, theoretically, predispose patients to EAMCs. Conversely, the authors 1 , 18 , 20 , 22 of several studies failed to show differences in plasma electrolyte concentrations in athletes with and those without EAMCs. Sodium supplementation did not differ between ultramarathoners with and those without EAMCs. If clinicians suspect hydration is a risk factor for recurrent EAMCs, we recommend sweat testing. Determining the sweat rate is relatively simple and only requires body weight to be measured before and after exercise. Clinicians must also know the duration of exercise and the volume or weight of any fluids ingested or lost ie, urination. Nonetheless, sweat electrolyte estimates are available for many sports. Combining sweat test results with a well-balanced, nutritious diet that considers the athlete's unique carbohydrate, fluid, and electrolyte needs will better ensure that he or she is prepared for exercise and minimize the risk of hyponatremia. Some clinicians use IV fluids to prevent EAMCs and believe they are effective. Although static stretching effectively treats EAMCs, 5 , 22 , 35 it appears to be ineffective as a prophylactic strategy. In a laboratory study, 56 three 1-minute bouts of static or proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation hold-relax with agonist contraction stretching did not lower cramp susceptibility. In observational studies of athletes, investigators 21 , 22 , 30 also consistently failed to demonstrate relationships among flexibility, range of motion, and stretching frequency, duration, or timing and EAMC occurrence. Moreover, Golgi tendon organ inhibition was unaffected by a single bout of clinician-applied static stretching to the triceps surae both immediately and up to 30 minutes poststretching. Neuromuscular retraining with exercise shows promise for EAMC prevention. Wagner et al 3 found that a triathlete's hamstrings EAMCs were eliminated by lowering hamstrings activity during running and improving gluteal strength and endurance. To achieve this outcome, the patient required few professional visits once a month for 8 months and just a short minute daily at-home protocol. Fatigue is hypothesized to be a main factor in EAMC development and overexertion is often tied to EAMCs, 9 so it is vital to ensure that athletes exercise with appropriate work-to-rest ratios. Advances in our understanding of EAMC pathogenesis have emerged in the last years and suggested that alterations in neuromuscular excitability and, to a much lesser extent, dehydration and electrolyte losses are the predominant factors in their pathogenesis. Strong evidence supports EAMC treatments that include exercise cessation rest and gentle stretching until abatement, followed by techniques to address the underlying precipitating factors. However, little patient-oriented evidence exists regarding the best methods for EAMC prevention. Therefore, rather than providing generalized advice, we recommend clinicians take a multifaceted and targeted approach that incorporates an individual's unique EAMC risk factors when trying to prevent EAMCs. Recipient s will receive an email with a link to 'An Evidence-Based Review of the Pathophysiology, Treatment, and Prevention of Exercise-Associated Muscle Cramps' and will not need an account to access the content. Subject: An Evidence-Based Review of the Pathophysiology, Treatment, and Prevention of Exercise-Associated Muscle Cramps. Sign In or Create an Account. Search Dropdown Menu. header search search input Search input auto suggest. User Tools Dropdown. Sign In. |

0 thoughts on “Exercise-induced cramps”