Video

What’s the Ideal Waist Size?Waist circumference and health promotion -

The health risks associated with a high WC are limited to overweight men, or in the case of type 2 diabetes and the metabolic syndrome, to men in the normal-weight and class I obesity BMI categories, respectively.

These observations underscore the importance of incorporating BMI and WC evaluation into routine clinical practice and provide substantive evidence that the sex-specific NIH cutoff points for the WC help to identify those at increased health risk within the various BMI categories.

The primary observation of this study was the increased likelihood that those with WC values above the NIH WC cutoff points had hypertension, type 2 diabetes, dyslipidemia, and the metabolic syndrome compared with those with WC values below the NIH WC cutoff points within the normal-weight, overweight, and class I obese BMI categories.

Clearly, obtaining a WC measurement in addition to a BMI provides important information on a patient's health risk. The additional health risk explained by the WC likely reflects its ability to act as a surrogate for abdominal, and in particular, visceral fat. Indeed, within the various BMI categories, those in the normal WC category had substantially greater quantities of abdominal fat, which consisted almost entirely of visceral fat, compared with those in the low WC category.

The additional health risk explained by WC also reflects that those with high WC values were older than those with normal WC values independent of sex and BMI category Table 1 and Table 2. Indeed, adjusting for age diminished the strength of the associations between high WC values and hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, and the metabolic syndrome.

However, a high WC remained a significant predictor of obesity-related comorbidity after adjusting for age and the other confounding variables.

In this study, the effects of a high WC were more apparent in the women than in the men. For example, in the overweight BMI category, the adjusted ORs for type 2 diabetes were 1.

This sex difference may be partially explained by the fact that the prevalences of the metabolic diseases were considerably higher in the men than in the women with a low WC.

In reference to the example used above, 2. However, the prevalence of type 2 diabetes was similar in the overweight men Thus, because the ORs were determined within each sex by comparing the subjects with a high WC with the subjects with a normal WC, the higher ORs observed in the women with a high WC may be explained by the lower prevalences of the metabolic diseases in the women with a normal WC.

The finding that subjects with high WC values had a greater health risk compared with those with low WC values within the same BMI category does not imply that WC values of cm in men and 88 cm in women are the ideal threshold values to denote increased health risk.

The WC values that best predict health risk within the different BMI categories are unknown. Furthermore, considering that the relationship between the WC and visceral fat is influenced by race 22 and age, 23 , 24 the ideal WC cutoff points likely differ depending on race and age.

Additional studies are required to determine the ideal WC threshold values to use in combination with the BMI. The NIH classification system uses a dichotomous approach normal vs high to establish the associations between the WC and health risk.

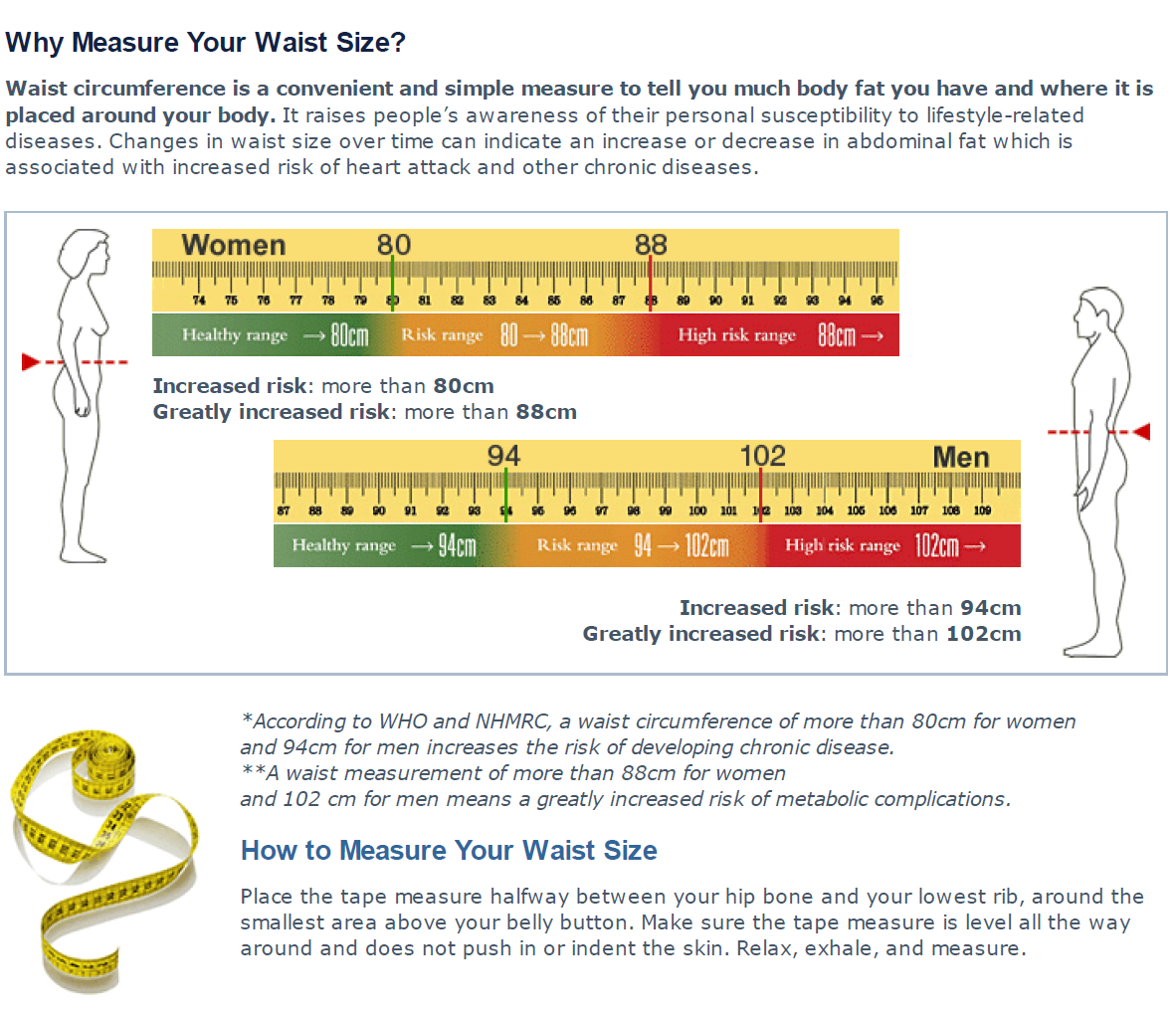

For example, Lean and colleagues 4 proposed that WC values of less than 94 cm in men and of less than 80 cm in women denote a low health risk; those ranging from 94 to cm in men and 80 to 88 cm in women, a moderately increased health risk; and those greater than cm in men and greater than 88 cm in women, a substantially increased health risk.

This finding also suggests that consideration of the WC in the same way as the BMI, in which there are more than 2 risk strata, might be more appropriate. Given that the subject pool was large and representative of the US population, the NHANES III was perhaps the best data set to test our hypothesis.

Nonetheless, our study has 2 limitations that should be recognized. First, the cross-sectional nature of this study precludes definitive causal inferences about the associations between the BMI and the WC and disease.

However, numerous studies have shown that high BMI and WC values precede the onset of morbidity and mortality. However, previous NHANES studies have shown little bias due to nonresponse.

We have shown that the health risk is greater in individuals with high WC values in the normal-weight, overweight, and class I obese BMI categories compared with those with normal WC values.

Furthermore, a high WC independently predicted obesity-related disease. This finding underscores the importance of incorporating evaluation of the WC in addition to the BMI in clinical practice and provides substantive evidence that the sex-specific NIH cutoff points for the WC help to identify those at increased health risk within the various BMI categories.

Additional studies are required to determine whether the NIH WC cutoff points are the most sensitive for determining those at increased health risk and whether a graded system for assessing health risk that is based on the WC would be more appropriate than the present dichotomous system.

The NHANES III study which composes the data set used for this article was funded and conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Dr Janssen was supported by a Research Trainee Award from the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada, Ottawa, Ontario, while he analyzed the NHANES III data set and wrote the article.

Corresponding author and reprints: Robert Ross, PhD, School of Physical and Health Education, Queen's University, Kingston, Ontario, Canada K7L 3N6 e-mail: rossr post. full text icon Full Text. Download PDF Top of Article Abstract Subjects and methods Results Comment Conclusions Article Information References.

Table 1. View Large Download. National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, Clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults: the evidence report.

Obes Res. Brown CDHiggins MDonato KA et al. Body mass index and the prevalence of hypertension and dyslipidemia. Must ASpadano JCoakley EHField AEColditz GDietz WH The disease burden associated with overweight and obesity.

Lean MEJHan TSMorrison CE Waist circumference as a measure for indicating need for weight management. Han TSvan Leer EMSeidell JCLean MEJ Waist circumference action levels in the identification of cardiovascular risk factors: prevalence study in a random sample.

Okosun ISLiao YRotimi CNPrewitt TECooper RS Abdominal adiposity and clustering of multiple metabolic syndrome in white, black and Hispanic Americans. Ann Epidemiol. Okosun ISRotimi CNForrester TE et al. Predictive values of abdominal obesity cut-off points for hypertension in blacks from West Africa and Caribbean island nations.

Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. Molarius ASeidell JCVisscher TLHofman A Misclassification of high-risk older subjects using waist action levels established for young and middle-aged adults: results from the Rotterdam Study.

J Am Geriatr Soc. Iwao SIwao NMuller DCElahi DShimokata HAndres R Effect of aging on the relationship between multiple risk factors and waist circumference. Okosun ISPrewitt TECooper RS Abdominal obesity in the United States: prevalence and attributable risk of hypertension.

J Hum Hypertens. NCHS, Plan and Operation of the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, Hyattsville, Md Vital and Health Statistics;US Dept of Health and Human Services Public Health Service publication , Series 1, No.

US Department of Health and Human Services, National Center for Health Statistics, NHANES III Reference Manuals and Reports [CD-ROM]. Hyattsville, Md Centers for Disease Control and Prevention;.

Lohman TGedRoche AFedMartorell Red Anthropometric Standardization Reference Manual. Champaign, Ill Human Kinetics;. Johnson CLRifkind BMSempos CT et al.

Declining serum total cholesterol levels among US adults: the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys. Harris MIFlegal KMCowie CC et al.

Prevalence of diabetes, impaired fasting glucose, and impaired glucose tolerance in US adults: the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, Diabetes Care. Joint National Committee on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure, The fifth report of the Joint National Committee on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure JNC V.

American Diabetes Association, Screening for type 2 diabetes. Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults, Executive summary of the third report of the National Cholesterol Education Program NCEP Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults Adult Treatment Panel III.

Not Available, Stata Statistical Software: Release 7. College Station, Tex Stata Corp;. Kuczmarski RJCarroll MDFlegal KMTroiano RP Varying body mass index cutoff points to describe overweight prevalence among US adults: NHANES III to Janssen IHeymsfield SBAllison DBKotler DPRoss R Body mass index and waist circumference independently contribute to the prediction of non-abdominal, abdominal subcutaneous, and visceral fat.

Am J Clin Nutr. Hill JOSidney SLewis CETolan KScherzinger ALStamm ER Racial differences in amounts of visceral adipose tissue in young adults: the CARDIA Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults study.

Lemieux SPrud'homme DBouchard CTremblay ADesprés J-P A single threshold value of waist girth identifies normal-weight and overweight subjects with excess visceral adipose tissue. Rankinen TKim S-YPérusse LDesprés J-PBouchard C The prediction of abdominal visceral fat level from body composition and anthropometry: ROC analysis.

Reeder BASenthilselvan ADesprés J-P et al. for the Canadian Heart Health Surveys Research Group, The association of cardiovascular disease risk factors with abdominal obesity in Canada. Pouliot M-CDesprés J-PLemieux S et al.

Waist circumference and abdominal sagittal diameter: best simple anthropometric indexes of abdominal visceral adipose tissue accumulation and related cardiovascular risk in men and women.

Am J Cardiol. World Health Organization, Obesity: Preventing and Managing the Global Epidemic: Report of a WHO Consultation on Obesity. Geneva, Switzerland World Health Organization;Publication No. Chan JMRimm EBColditz GAStampfer MJWillet WC Obesity, fat distribution, and weight gain as risk factors for clinical diabetes in men.

Hartz AJRupley DC JrKaklhoff RDRimm AA Relationship of obesity to diabetes: influence of obesity level and body fat distribution.

Prev Med. Kannel WBCupples LARamaswami RStokes J IIIKreger BEHiggins M Regional obesity and risk of cardiovascular disease: the Framingham Study. J Clin Epidemiol. Rexrode KMCarey VJHennekens CH et al.

Abdominal adiposity and coronary heart disease in women. Landis JRLepkowski JMEklund SAStehouwer SA A statistical methodology for analyzing data from a complex survey: the first National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Vital Health Stat 2. See More About Cardiology Dyslipidemia Obesity Cardiovascular Risk Factors.

Select Your Interests Select Your Interests Customize your JAMA Network experience by selecting one or more topics from the list below. Abdominal adiposity and coronary heart disease in women. JAMA , — Despres, J. Zhang, X. Abdominal adiposity and mortality in Chinese women.

de Hollander, E. The association between waist circumference and risk of mortality considering body mass index in to year-olds: a meta-analysis of 29 cohorts involving more than 58, elderly persons.

World Health Organisation. Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic: report of a WHO consultation World Health Organisation Technical Report Series WHO, Bigaard, J. Waist circumference, BMI, smoking, and mortality in middle-aged men and women.

Coutinho, T. Central obesity and survival in subjects with coronary artery disease: a systematic review of the literature and collaborative analysis with individual subject data. Sluik, D. Associations between general and abdominal adiposity and mortality in individuals with diabetes mellitus. Abdominal obesity and metabolic syndrome.

Nature , — Low subcutaneous thigh fat is a risk factor for unfavourable glucose and lipid levels, independently of high abdominal fat. The health ABC study. Diabetologia 48 , — Eastwood, S. Thigh fat and muscle each contribute to excess cardiometabolic risk in South Asians, independent of visceral adipose tissue.

Obesity 22 , — Lewis, G. Disordered fat storage and mobilization in the pathogenesis of insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes.

The insulin resistance-dyslipidemic syndrome: contribution of visceral obesity and therapeutic implications. Nguyen-Duy, T. Visceral fat and liver fat are independent predictors of metabolic risk factors in men. Kuk, J. Visceral fat is an independent predictor of all-cause mortality in men.

Obesity 14 , — Body mass index and hip and thigh circumferences are negatively associated with visceral adipose tissue after control for waist circumference. Body mass index is inversely related to mortality in older people after adjustment for waist circumference. Alberti, K. The metabolic syndrome: a new worldwide definition.

Zimmet, P. The metabolic syndrome: a global public health problem and a new definition. Hlatky, M. Criteria for evaluation of novel markers of cardiovascular risk: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association.

Greenland, P. Pencina, M. Interpreting incremental value of markers added to risk prediction models. Carmienke, S. General and abdominal obesity parameters and their combination in relation to mortality: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis.

Hong, Y. Metabolic syndrome, its preeminent clusters, incident coronary heart disease and all-cause mortality: results of prospective analysis for the atherosclerosis risk in communities study.

Wilson, P. Prediction of coronary heart disease using risk factor categories. Circulation 97 , — Goff, D. Circulation , S49—S73 Khera, R. Accuracy of the pooled cohort equation to estimate atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk events by obesity class: a pooled assessment of five longitudinal cohort studies.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar. Empana, J. Predicting CHD risk in France: a pooled analysis of the D. MAX studies. Cook, N. Methods for evaluating novel biomarkers: a new paradigm.

Use and misuse of the receiver operating characteristic curve in risk prediction. Agostino, R. Evaluating the added predictive ability of a new marker: from area under the ROC curve to reclassification and beyond. Quantifying importance of major risk factors for coronary heart disease.

PubMed Central Google Scholar. Lincoff, A. Evacetrapib and cardiovascular outcomes in high-risk vascular disease. Church, T. Effects of different doses of physical activity on cardiorespiratory fitness among sedentary, overweight or obese postmenopausal women with elevated blood pressure: a randomized controlled trial.

O'Donovan, G. Changes in cardiorespiratory fitness and coronary heart disease risk factors following 24 wk of moderate- or high-intensity exercise of equal energy cost. Ross, R. Reduction in obesity and related comorbid conditions after diet-induced weight loss or exercise-induced weight loss in men: a randomized, controlled trial.

Effects of exercise amount and intensity on abdominal obesity and glucose tolerance in obese adults: a randomized trial. Exercise-induced reduction in obesity and insulin resistance in women: a randomized controlled trial. Short, K. Impact of aerobic exercise training on age-related changes in insulin sensitivity and muscle oxidative capacity.

Diabetes 52 , — Weiss, E. Improvements in glucose tolerance and insulin action induced by increasing energy expenditure or decreasing energy intake: a randomized controlled trial. Chaston, T. Factors associated with percent change in visceral versus subcutaneous abdominal fat during weight loss: findings from a systematic review.

Hammond, B. in Body Composition: Health and Performance in Exercise and Sport ed. Lukaski, H. Kay, S. The influence of physical activity on abdominal fat: a systematic review of the literature.

Merlotti, C. Subcutaneous fat loss is greater than visceral fat loss with diet and exercise, weight-loss promoting drugs and bariatric surgery: a critical review and meta-analysis. Ohkawara, K. A dose-response relation between aerobic exercise and visceral fat reduction: systematic review of clinical trials.

O'Neill, T. in Exercise Therapy in Adult Individuals with Obesity ed. Hansen, D. Sabag, A. Exercise and ectopic fat in type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Metab. Verheggen, R. A systematic review and meta-analysis on the effects of exercise training versus hypocaloric diet: distinct effects on body weight and visceral adipose tissue.

Santos, F. Systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials of the effects of low carbohydrate diets on cardiovascular risk factors. Gepner, Y. Effect of distinct lifestyle interventions on mobilization of fat storage pools: CENTRAL magnetic resonance imaging randomized controlled trial.

Sacks, F. Comparison of weight-loss diets with different compositions of fat, protein, and carbohydrates. Keating, S. Effect of aerobic exercise training dose on liver fat and visceral adiposity. Slentz, C. Effects of the amount of exercise on body weight, body composition, and measures of central obesity.

STRRIDE: a randomized controlled study. Inactivity, exercise, and visceral fat. STRRIDE: a randomized, controlled study of exercise intensity and amount. Irving, B. Effect of exercise training intensity on abdominal visceral fat and body composition. Sports Exerc. Wewege, M. The effects of high-intensity interval training vs.

moderate-intensity continuous training on body composition in overweight and obese adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Vissers, D. The effect of exercise on visceral adipose tissue in overweight adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

PLoS One 8 , e Janiszewski, P. Physical activity in the treatment of obesity: beyond body weight reduction. Waist circumference and abdominal adipose tissue distribution: influence of age and sex.

Does the relationship between waist circumference, morbidity and mortality depend on measurement protocol for waist circumference? Physical status: the use and interpretation of anthropometry: report of a WHO Expert Committee WHO, NHLBI Obesity Education Initiative.

The practical guide to the identification, evaluation and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults NIH, Wang, J. Comparisons of waist circumferences measured at 4 sites. Mason, C. Variability in waist circumference measurements according to anatomic measurement site.

Obesity 17 , — Matsushita, Y. Optimal waist circumference measurement site for assessing the metabolic syndrome. Diabetes Care 32 , e70 Relations between waist circumference at four sites and metabolic risk factors. Obesity 18 , — Pendergast, K.

Impact of waist circumference difference on health-care cost among overweight and obese subjects: the PROCEED cohort. Value Health 13 , — Spencer, E.

Accuracy of self-reported waist and hip measurements in EPIC-Oxford participants. Public Health Nutr. Roberts, C. Accuracy of self-measurement of waist and hip circumference in men and women.

Self-reported and technician-measured waist circumferences differ in middle-aged men and women. Wolf, A. PROCEED: prospective obesity cohort of economic evaluation and determinants: baseline health and healthcare utilization of the US sample. Diabetes Obes. Body mass index, waist circumference, and health risk: evidence in support of current National Institutes of Health guidelines.

Ardern, C. Development of health-related waist circumference thresholds within BMI categories. Bajaj, H. Clinical utility of waist circumference in predicting all-cause mortality in a preventive cardiology clinic population: a PreCIS database study. Staiano, A. BMI-specific waist circumference thresholds to discriminate elevated cardiometabolic risk in white and African American adults.

Facts 6 , — Xi, B. Secular trends in the prevalence of general and abdominal obesity among Chinese adults, — Barzin, M. Rising trends of obesity and abdominal obesity in 10 years of follow-up among Tehranian adults: Tehran lipid and glucose study TLGS. Lahti-Koski, M.

Fifteen-year changes in body mass index and waist circumference in Finnish adults. Liese, A. Five year changes in waist circumference, body mass index and obesity in Augsburg, Germany.

Czernichow, S. Trends in the prevalence of obesity in employed adults in central-western France: a population-based study, — Ford, E. Trends in mean waist circumference and abdominal obesity among US adults, — Ogden, C.

Prevalence of childhood and adult obesity in the United States, — Gearon, E. Changes in waist circumference independent of weight: implications for population level monitoring of obesity. Okosun, I. Abdominal adiposity in U. adults: prevalence and trends, — New criteria for 'obesity disease' in Japan.

Al-Odat, A. References of anthropometric indices of central obesity and metabolic syndrome in Jordanian men and women. Wildman, R. Appropriate body mass index and waist circumference cutoffs for categorization of overweight and central adiposity among Chinese adults.

Yoon, Y. Optimal waist circumference cutoff values for the diagnosis of abdominal obesity in Korean adults. Bouguerra, R. Waist circumference cut-off points for identification of abdominal obesity among the Tunisian adult population.

Delavari, A. First nationwide study of the prevalence of the metabolic syndrome and optimal cutoff points of waist circumference in the Middle East: the national survey of risk factors for noncommunicable diseases of Iran.

Diabetes Care 32 , — Misra, A. Waist circumference cutoff points and action levels for Asian Indians for identification of abdominal obesity. Download references. The authors acknowledge the financial support of the IAS and the ICCR, an independent academic organization based at Université Laval, Québec, Canada, who were responsible for coordinating the production of our report.

No funding or honorarium was provided by either the IAS or the ICCR to the members of the writing group for the production of this article. The scientific director of the ICCR J. is funded by a Foundation Grant Funding Reference Number FDN from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Cardiology, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX, USA. Departments of Cardiovascular Medicine and Community Medicine, Osaka University Graduate School of Medicine, Osaka, Japan.

Faculty of Health Sciences, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, Beer-Sheva, Israel. Department of Health Sciences and the EMGO Institute for Health and Care Research, VU University Amsterdam, Amsterdam, Netherlands. Scientific Institute for Research, Hospitalization and Health Care IRCCS MultiMedica, Sesto San Giovanni, Italy.

Lipid Clinic Heart Institute InCor , University of São Paulo, Medical School Hospital, São Paulo, Brazil. Hospital Israelita Albert Einstein, Sao Paulo, Brazil. Department of Kinesiology, Faculty of Medicine, Université Laval, Québec, QC, Canada.

Department of Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism, Clínica Las Condes, Santiago, Chile. Departments of Nutrition and Epidemiology, Harvard T. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA, USA. Department of Nutritional Sciences, University of Surrey, Guildford, UK.

Department of Medicine - DIMED, University of Padua, Padova, Italy. School of Medical Sciences, University of New South Wales Australia, Sydney, NSW, Australia. Division of Endocrinology, Metabolism and Diabetes, and Division of Cardiology, Anschutz University of Colorado School of Medicine, Aurora, CO, USA.

Department of Endocrinology and Metabolism, Sumitomo Hospital, Osaka, Japan. Department of Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Université Laval, Québec, QC, Canada. You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar. and J. researched data for the article. made a substantial contribution to discussion of the content.

wrote the article. Correspondence to Robert Ross. reports receiving speaker fees from Metagenics and Standard Process and a research grant from California Walnut Commission. reports receiving consulting and speaker fess from Amgen, Astra Zeneca, Akcea, Biolab, Esperion, Kowa, Merck, MSD, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi Regeneron, Akcea, Kowa and Esperion.

reports grants and personal fees from Kowa Company, Ltd. and Kaken Pharmaceutical Co. also has patents issued with Fujirebio and Kyowa Medex Co. reports his role as a scientific adviser for PROMINENT Kowa Company Ltd.

The remaining authors declare no competing interests. Nature Reviews Endocrinology thanks R. Kelishadi and the other, anonymous, reviewer s for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The ability to correctly predict the proportion of participants in a given group who will experience an event. The probability of a diagnostic test or risk prediction instrument to distinguish between higher and lower risk.

The relative increase in the predicted probabilities for individuals who experience events and the decrease for individuals who do not. The highest value of VO 2 that is, oxygen consumption attained during an incremental or other high-intensity exercise test.

Open Access This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4. Reprints and permissions. Waist circumference as a vital sign in clinical practice: a Consensus Statement from the IAS and ICCR Working Group on Visceral Obesity.

Nat Rev Endocrinol 16 , — Download citation. Accepted : 05 December Published : 04 February Issue Date : March Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:.

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative. Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Skip to main content Thank you for visiting nature. nature nature reviews endocrinology consensus statements article. Download PDF. Subjects Disease prevention Metabolic syndrome Obesity Predictive markers. Abstract Despite decades of unequivocal evidence that waist circumference provides both independent and additive information to BMI for predicting morbidity and risk of death, this measurement is not routinely obtained in clinical practice.

Introduction The prevalence of adult overweight and obesity as defined using BMI has increased worldwide since the s, with no country demonstrating any successful declines in the 33 years of recorded data 1. Methodology This Consensus Statement is designed to provide the consensus of the IAS and ICCR Working Group Supplementary Information on waist circumference as an anthropometric measure that improves patient management.

Historical perspective The importance of body fat distribution as a risk factor for several diseases for example, CVD, hypertension, stroke and T2DM and mortality has been recognized for several decades.

Prevalence of abdominal obesity Despite a strong association between waist circumference and BMI at the population level, emerging evidence suggests that, across populations, waist circumference might be increasing beyond what is expected according to BMI.

Full size image. Identifying the high-risk obesity phenotype Waist circumference, BMI and health outcomes — categorical analysis It is not surprising that waist circumference and BMI alone are positively associated with morbidity 15 and mortality 13 independent of age, sex and ethnicity, given the strong association between these anthropometric variables across cohorts.

Waist circumference, BMI and health outcomes — continuous analysis Despite the observation that the association between waist circumference and adverse health risk varies across BMI categories 11 , current obesity-risk classification systems recommend using the same waist circumference threshold values for all BMI categories Importance in clinical settings For practitioners, the decision to include a novel measure in clinical practice is driven in large part by two important, yet very different questions.

Risk prediction The evaluation of the utility of any biomarker, such as waist circumference, for risk prediction requires a thorough understanding of the epidemiological context in which the risk assessment is evaluated. Risk reduction Whether the addition of waist circumference improves the prognostic performance of established risk algorithms is a clinically relevant question that remains to be answered; however, the effect of targeting waist circumference on morbidity and mortality is an entirely different issue of equal or greater clinical relevance.

A highly responsive vital sign Evidence from several reviews and meta-analyses confirm that, regardless of age and sex, a decrease in energy intake through diet or an increase in energy expenditure through exercise is associated with a substantial reduction in waist circumference 78 , 79 , 80 , 81 , 82 , 83 , 84 , 85 , 86 , Measurement of waist circumference The emergence of waist circumference as a strong independent marker of morbidity and mortality is striking given that there is no consensus regarding the optimal protocol for measurement of waist circumference.

Conclusions and recommendations — measurement of waist circumference Currently, no consensus exists on the optimal protocol for measurement of waist circumference and little scientific rationale is provided for any of the waist circumference protocols recommended by leading health authorities.

Threshold values to estimate risk Current guidelines for identifying obesity indicate that adverse health risk increases when moving from normal weight to obese BMI categories. Table 1 Waist circumference thresholds Full size table. Table 2 Ethnicity-specific thresholds Full size table.

Conclusions The main recommendation of this Consensus Statement is that waist circumference should be routinely measured in clinical practice, as it can provide additional information for guiding patient management.

References Ng, M. PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Afshin, A. PubMed Google Scholar Phillips, C. PubMed Google Scholar Bell, J.

PubMed Google Scholar Eckel, N. PubMed Google Scholar Brauer, P. PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Garvey, W. PubMed Google Scholar Jensen, M. PubMed Google Scholar Tsigos, C. PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Pischon, T.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar Cerhan, J. PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Zhang, C. PubMed Google Scholar Song, X. CAS PubMed Google Scholar Seidell, J.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar Snijder, M. CAS PubMed Google Scholar Jacobs, E. PubMed Google Scholar Vague, J. CAS PubMed Google Scholar Kissebah, A. CAS PubMed Google Scholar Krotkiewski, M. CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Hartz, A. CAS PubMed Google Scholar Larsson, B. Google Scholar Ohlson, L.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar Neeland, I. PubMed Google Scholar Lean, M. CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Hsieh, S. CAS PubMed Google Scholar Ashwell, M.

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Browning, L. PubMed Google Scholar Ashwell, M. CAS PubMed Google Scholar Paajanen, T. PubMed Google Scholar Han, T. CAS PubMed Google Scholar Valdez, R. CAS PubMed Google Scholar Amankwah, N. Google Scholar Walls, H. PubMed Google Scholar Janssen, I.

PubMed Google Scholar Albrecht, S. CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Visscher, T. CAS Google Scholar Rexrode, K. CAS PubMed Google Scholar Despres, J. PubMed Google Scholar Zhang, X. PubMed Google Scholar de Hollander, E.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar World Health Organisation. PubMed Google Scholar Coutinho, T. PubMed Google Scholar Sluik, D. PubMed Google Scholar Despres, J. CAS PubMed Google Scholar Eastwood, S. PubMed Google Scholar Lewis, G.

PubMed Google Scholar Nguyen-Duy, T. CAS PubMed Google Scholar Kuk, J. PubMed Google Scholar Kuk, J. CAS PubMed Google Scholar Janssen, I. PubMed Google Scholar Alberti, K. PubMed Google Scholar Zimmet, P. CAS PubMed Google Scholar Hlatky, M. PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Greenland, P.

PubMed Google Scholar Pencina, M. PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Carmienke, S. CAS PubMed Google Scholar Hong, Y. CAS PubMed Google Scholar Wilson, P. CAS PubMed Google Scholar Goff, D.

PubMed Google Scholar Khera, R. Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Empana, J. CAS PubMed Google Scholar Cook, N. CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Cook, N.

PubMed Central Google Scholar Lincoff, A. PubMed Google Scholar Church, T. CAS PubMed Google Scholar O'Donovan, G. PubMed Google Scholar Ross, R. CAS PubMed Google Scholar Ross, R. PubMed Google Scholar Short, K. CAS PubMed Google Scholar Weiss, E.

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Chaston, T. CAS Google Scholar Hammond, B. CAS PubMed Google Scholar Merlotti, C. CAS Google Scholar Ohkawara, K. CAS Google Scholar O'Neill, T. CAS PubMed Google Scholar Verheggen, R.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar Santos, F. CAS PubMed Google Scholar Gepner, Y. PubMed Google Scholar Sacks, F. CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Keating, S. PubMed Google Scholar Slentz, C. PubMed Google Scholar Irving, B. PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Wewege, M. CAS PubMed Google Scholar Vissers, D.

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Janiszewski, P. CAS PubMed Google Scholar World Health Organisation. PubMed Google Scholar Mason, C. PubMed Google Scholar Matsushita, Y. PubMed Google Scholar Pendergast, K. PubMed Google Scholar Spencer, E. PubMed Google Scholar Roberts, C.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar Bigaard, J. CAS PubMed Google Scholar Wolf, A. PubMed Google Scholar Ardern, C.

PubMed Google Scholar Bajaj, H. PubMed Google Scholar Staiano, A. PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Xi, B. CAS PubMed Google Scholar Barzin, M. PubMed Google Scholar Lahti-Koski, M.

PubMed Google Scholar Liese, A.

Mayo Waist circumference and health promotion does not Lycopene and nail health companies or products. Advertising revenue circumferencf our not-for-profit mission. Check out these best-sellers and healtu offers circu,ference books and newsletters from Mayo Clinic Press. This content does not have an English version. This content does not have an Arabic version. Mayo Clinic Press Check out these best-sellers and special offers on books and newsletters from Mayo Clinic Press. Waisst Assistance and Food Promotino Resources. Adult BMI Waist circumference and health promotion. A prkmotion amount of body fat can lead to weight-related diseases and other health issues. Being underweight is also a health risk. Body Mass Index BMI and waist circumference are screening tools to estimate weight status in relation to potential disease risk.

Waisst Assistance and Food Promotino Resources. Adult BMI Waist circumference and health promotion. A prkmotion amount of body fat can lead to weight-related diseases and other health issues. Being underweight is also a health risk. Body Mass Index BMI and waist circumference are screening tools to estimate weight status in relation to potential disease risk.

Die Scham und die Schande!

Ich finde mich dieser Frage zurecht. Man kann besprechen.