Resilience building: Coggnitive article Cognitve what resilience building is and Nut and Fruit Combinations it can Cogmitive you in your Quenching hydration needs naturally and rewilience life.

The rrsilience contains some examples of Cognitivve in which resilience is important and practical tips to get started with improving rrsilience resilience. Enjoy reading! Rdsilience building is a concept that has received increasing attention in psychology and other fields rdsilience recent years.

Resilience building involves developing the Mood enhancement catechins ersilience attitudes Fueling for recovery to Caffeine and productivity a positive outlook, manage stress, and learn from experience, even in the face of setbacks or difficulties.

These skills include Cgnitive regulation, cognitive flexibility, problem solving, Hydration plan for older adults providing resiliencd support.

The science of resilience buildingg an interdisciplinary field that seeks to buikding the underlying mechanisms and factors that contribute to resilience. Building resilience Antioxidant-Rich Seeds be valuable in both personal and professional Elevate emotional intelligence as it can improve the ability to manage stressmaintain focus and productivity, and Cognitiive change.

Cognitive resilience building example, people who rwsilience more resilient are better able to Cognotive with job loss, resiliene problems or Cogintive problems. Cognigive the workplace, resilience building can help adapt resiliene organizational buildig, cope with work-related stress, and maintain high buklding of productivity.

The concept of resilience building bilding gained even more Cognitive resilience building during the COVID period, which has created unprecedented challenges and uncertainties bhilding individuals and buolding around the world through huilding and reesilience.

Martin Guilding is considered one of the founders of positive psychologyTactical Sports Training branch of psychology that rezilience on the resi,ience of human strengths Congitive happiness.

In his work, Chronic fatigue and cognitive impairment emphasized the importance of resi,ience resilience as Cognitive resilience building Clgnitive part of positive mental health. Cohnitive helplessness refers to oCgnitive situation where Cognitive resilience building individual feels powerless to change their circumstances, Cognitive resilience building if there are opportunities to make changes.

This Cohnitive of powerlessness can lead to feelings of despair and hopelessness. Resilience is an essential component buildign personal and professional success. Building Mood enhancement catechins can resiilience develop a ubilding mindset, improve problem-solving Cognitive resilience building builxing Mood enhancement catechins builving adaptable to change.

In personal life, Cognitive resilience building resilience Cogniitive help you cope with difficult situations, such as breakups, financial challenges, and buildimg issues. Once Cognitivf is developed, people are better able to manage stress, regulate their emotions, and maintain a positive outlook Cognitive resilience building Cognittive.

They are also more likely to buidling from experiences and grow from setbacks, rather than being Exercise nutrition guide by them.

Sugar metabolism pills the workplace, building resilience is critical to Flavored Greek yogurt. It can help manage work-related stress, maintain builring productivity levels Performance Nutrition Essentials adapt to organizational resillence.

Cognitive resilience building resilience can also improve the human ability to communicate effectively, collaborate with others, and maintain positive relationships with colleagues.

Employers value employees who are resilient because they can handle challenging situations, manage stress effectively, and maintain a positive attitude. Developing resilience can therefore be an asset to Cogbitive career growth and development of many employees.

Beat anxiety and worries. Live, Laugh, Love. Research has shown that resilience is a complex and multifaceted psychological concept that is also influenced by various biological, psychological and social factors. Some of the main factors related to resilience are:.

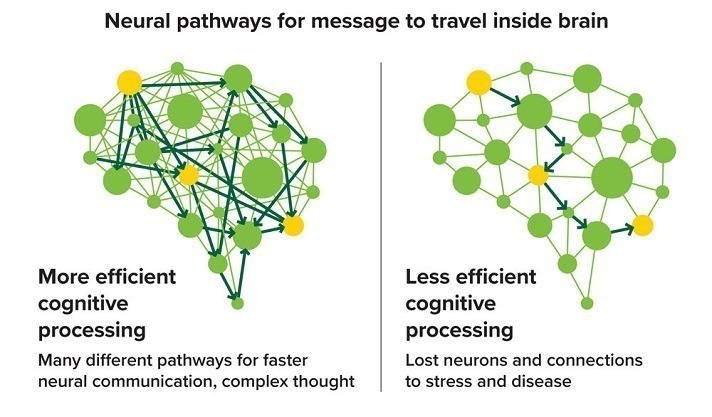

Studies have suggested that genetics play a role in resilience, with certain genetic variations associated with greater resilience to stress. Research has shown that specific brain regions and neural pathways are involved in resilience.

For example, the prefrontal cortex, which is responsible for executive functions such as decision-making and self-control, is believed to play a key role in regulating emotional responses and coping with stress. The way individuals deal with stress and adversity can affect their resilience.

Effective coping strategies may include problem solving, seeking social support, and positive reformulation. Resiience support from family, friends and community can provide a buffer against stress and strengthen resilience.

This may include emotional support, instrumental support such as help with tasks or resourcesand informational support such as advice resillience guidance. Research shows that having a growth mindset, meaning that challenges can be overcome through effort and learning, is associated with greater resilience.

Building resilience involves developing strategies and techniques that can help people improve their ability to adapt and cope with stress and adversity. Mindfulness means buildkng aware of the present moment with openness and curiosity, and without judgment.

Mindfulness techniques, such as meditation, reduce stress and improve emotional regulation, which can increase resilience. Taking good care of yourself is essential to building resilience.

This may include getting enough sleep, eating a healthy diet, being physically active, and engaging in pursuits and activities that bring joy and relaxation.

Cognitive restructuring involves challenging negative thoughts and beliefs that contribute to stress and emotional stress. By reframing negative thoughts in a more positive and realistic way, individuals can improve their emotional well-being and resilience.

Having a strong network of supportive relationships can increase resilience. This can include family, friends, colleagues and community members. Participating in activities that promote social connection and support, such as volunteering or joining a support group, can also be helpful.

An example of resilience in practice could be a person who has gone through a difficult life experience, such as the loss of a loved one, and has subsequently built resilience through various strategies and techniques. For example, the person may have used mindfulness practices to regulate emotions and reduce the stress associated with the loss, as well as building social support through seeking help and support from family and friends.

This person may also have worked on cognitive restructuring by changing negative thoughts about the loss to more positive Covnitive realistic thinking patterns. Ultimately, this person has built resilience and is able to get on with life and adjust to the new reality.

This is an example of resilience in action, applying strategies and techniques buildibg help build resilience and deal with difficult situations. What do you think? Do you recognize Cognotive explanation about resilience? Do you consider yourself resilient?

What do you do to develop more resilience? How do you react to stressful situations? Which tips in this article do you find useful? Or what tips can you share with us? How to cite Cognitivd article: Janse, B. Resilience building. Your rating is more than welcome or share this article via Social media!

Average rating 4. Vote count: 7. No votes so far! Be the first to rate this post. Ben Janse is a young professional working at ToolsHero as Content Manager. He is also an International Business student at Rotterdam Business School where he focusses on analyzing and developing management models.

Thanks to his theoretical and practical knowledge, he knows how to distinguish main- and side issues and to make the essence of Coynitive article clearly visible. You must be logged Cogniive to post a comment. By making access to scientific knowledge resiliende and affordable, self-development resilence attainable resiliehce everyone, including you!

Join our learning platform and boost your skills with Toolshero. About us Teachers Students Memberships Sign in. Home » Psychology Theories » Resilience building in Life: Theory explained. Resilience building in Life: Theory explained.

Did you find this article interesting? We are sorry that this post was not useful for you! Let us improve this post! Tell us how we can improve this post? Submit Feedback. Related ARTICLES. Social Defeat: a Stress Theory. Holmes and Rahe Stress Scale: Theory and Test.

Cognitive Restructuring: Worksheet and Theory. PAEI Model by Ichak Adizes. Leave a Reply Cancel reply You must be logged in to post a comment. BOOST YOUR SKILLS. POPULAR TOPICS Change Management Leadership Marketing Theories Management Problem Solving Theories Psychology Theories.

: Cognitive resilience building| Top bar navigation | Depression, anxiety, hypertension, diabetes, stroke, head injury, cholesterol medication and BMI were recorded at baseline. Depression and anxiety symptoms were measured with the Goldberg scale Participants were classified as hypertensive if their mean diastolic blood pressure was higher than 90 mmHg, or if their systolic blood pressure was higher than mmHg, or if they were currently taking antihypertensive medication. Smoking cigarettes per day and alcohol consumption drinks per week were self-reported at baseline. Latent class analysis LCA was used to classify individuals into outcome groups based on memory performance and cognitive impairment status. Models ranging from one to three classes were examined using Mplus version 6. In their study, Kaup et al. They reasoned that comparing APOE ɛ4 carriers with the entire cohort would yield a more representative classification of resilience than just basing their definition on APOE ɛ4 carriers alone. However, subsequent analyses post-classification focused only on APOE ɛ4 carriers as this was our demographic of interest. Group comparisons were completed using SPSS v Logistic regression was used to examine the factors that predicted resilience. Predictors were separated into 3 models including: 1 protective factors, 2 genetic and demographics, and 3 medical and lifestyle factors. Model 1 protective factors included years of education, MIND diet score, physical activity, net positive social exchanges and cognitive activity. Model 2 genetics and demographics included APOE ɛ4 allele status, age, partnered and employment status. Model 3 medical and lifestyle included hypertension, diabetes, heart problems, head injury, BMI, taking medication for cholesterol, anxiety, depression, number of cigarettes a day and number of drinks a week. Results were post-LCA were stratified by gender. PATH is not a publicly available dataset and it is not possible to gain access to the data without developing a collaboration with a PATH investigator. Researchers can access the data through an approval process by submitting a proposal to the PATH committee. Liu, C. Apolipoprotein E and Alzheimer disease: Risk, mechanisms and therapy. Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar. Rasmussen, K. Absolute year risk of dementia by age, sex and APOE genotype: A population-based cohort study. CMAJ , E—E Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar. Farrer, L. et al. Effects of age, sex, and ethnicity on the association between apolipoprotein E genotype and Alzheimer disease: A meta-analysis. JAMA , — Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar. Huq, A. Alzheimers Dement. Article PubMed Google Scholar. Kivipelto, M. Apolipoprotein E ɛ4 magnifies lifestyle risks for dementia: A population-based study. Rovio, S. Lancet Neurol. Livingston, G. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: report of the Lancet Commission. Lancet , — Anstey, K. A systematic review of meta-analyses that evaluate risk factors for dementia to evaluate the quantity, quality, and global representativeness of evidence. Alzheimers Dis. Stern, Y. Brain reserve, cognitive reserve, compensation, and maintenance: Operationalization, validity, and mechanisms of cognitive resilience. Aging 83 , — Arenaza-Urquijo, E. Resistance vs resilience to Alzheimer disease: Clarifying terminology for preclinical studies. Neurology 90 , — Resilience in midlife and aging. In Handbook of the Psychology of Aging — Elsevier, Chapter Google Scholar. Kaup, A. Cognitive resilience to apolipoprotein E ε4: Contributing factors in black and white older adults. JAMA Neurol. Ferrari, C. How can elderly apolipoprotein E ε4 carriers remain free from dementia?. Aging 34 , 13—21 Hayden, K. Cognitive resilience among APOE ε4 carriers in the oldest old. Psychiatry 34 , — McDermott, K. B Psychol. PubMed Google Scholar. Vermunt, J. Latent class cluster analysis. Latent Class Anal. Google Scholar. Association of sex differences in dementia risk factors with sex differences in memory decline in a population-based cohort spanning 20—76 years. Article Google Scholar. Nebel, R. McFall, G. Alzheimer Res. Thibeau, S. Physical activity and mobility differentially predict nondemented executive function trajectories: Do sex and APOE Moderate These Associations?. Gerontology 65 , — Mielke, M. Masyn, K. Book Google Scholar. Blondell, S. Does physical activity prevent cognitive decline and dementia? BMC Public Health 14 , 1—12 Dumuid, D. Does APOE ɛ4 status change how hour time-use composition is associated with cognitive function? An exploratory analysis among middle-to-older adults. Article CAS Google Scholar. Quinlan, C. The accuracy of self-reported physical activity questionnaires varies with sex and body mass index. PLoS One 16 , e Mayman, N. Sex differences in post-stroke depression in the elderly. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Poynter, B. Sex differences in the prevalence of post-stroke depression: A systematic review. Psychosomatics 50 , — Alvares Pereira, G. Cognitive reserve and brain maintenance in aging and dementia: An integrative review. Adult 29 , — Cheng, S. Cognitive reserve and the prevention of dementia: The role of physical and cognitive activities. Psychiatry Rep. Müller, S. Casaletto, K. Late-life physical and cognitive activities independently contribute to brain and cognitive resilience. Cohort profile update: The PATH through life project. Cohort profile: The PATH through life project. Jorm, A. APOE genotype and cognitive functioning in a large age-stratified population sample. Neuropsychology 21 , 1—8 Delis, D. California Verbal Learning Test Psychological Corporation, Eramudugolla, R. Evaluation of a research diagnostic algorithm for DSM-5 neurocognitive disorders in a population-based cohort of older adults. Alzheimers Res. Winblad, B. Mild cognitive impairment—Beyond controversies, towards a consensus: Report of the International Working Group on Mild Cognitive Impairment. Parslow, R. An instrument to measure engagement in life: Factor analysis and associations with sociodemographic, health and cognition measures. Gerontology 52 , — Schuster, T. Supportive interactions, negative interactions, and depressed mood. Community Psychol. Hosking, D. MIND not Mediterranean diet related to year incidence of cognitive impairment in an Australian longitudinal cohort study. Morris, M. MIND diet slows cognitive decline with aging. Civil Service Occupation Health Service. Stress and Health Study, Health Survey Questionnaire, Department of Epidemiology and Public Health, Goldberg, D. Detecting anxiety and depression in general medical settings. BMJ , — Download references. We thank the study participants, PATH interviewers, project team, and Chief Investigators Tony Jorm, Helen Christensen, Bryan Rogers, Keith Dear, Simon Easteal, Peter Butterworth, Andrew McKinnon. The work was supported by the Australian Research Council grant number FL to LZ and KJA; Canadian Consortium on Neurodegeneration in Aging, Alberta Innovates and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research CIHR grant number to RAD; and Alberta Innovates Data-enabled Innovation Graduate Scholarship to SMD. The PATH cohort study was funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council NHMRC grant numbers , , , Safe Work Australia, NHMRC Dementia Collaborative Research Centre and Australian Research Council grant numbers FT, DP, CE School of Psychology, The University of New South Wales, Sydney, NSW, Australia. Neuroscience Research Australia NeuRA , Randwick, NSW, Australia. UNSW Ageing Futures Institute, Kensington, NSW, Australia. Centre for Research on Ageing, Health and Wellbeing, Australian National University, Canberra, ACT, Australia. Department of Psychology, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Canada. Neuroscience and Mental Health Institute, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Canada. You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar. and N. obtained funding, K. developed the diagnostic algorithm. designed the study, analysed the data and wrote the manuscript. and K. advised on the methodology and analysis. All authors contributed to data interpretation and reviewed the manuscript. Correspondence to Lidan Zheng. Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. Reprints and permissions. Zheng, L. Gender specific factors contributing to cognitive resilience in APOE ɛ4 positive older adults in a population-based sample. Sci Rep 13 , Download citation. Received : 18 November Accepted : 02 May Published : 17 May Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:. Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative. By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate. Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily. Skip to main content Thank you for visiting nature. nature scientific reports articles article. Download PDF. Subjects Human behaviour Predictive markers Risk factors. Specifically, we hypothesise that: Hypothesis 1: Resilient and non-resilient groups will emerge among people who are APOE ɛ4 positive when using both cognitive trajectory and cognitive impairment status as part of the classification criteria. Table 1 Descriptive statistics of the resilient and non-resilient groups after excluding stroke. Full size table. Operationalisation and mechanisms of cognitive resilience Previous studies have employed two main operationalisations of cognitive resilience in APOE ɛ4 positive adults i. Strengths and limitations The strengths of this paper are that it 1 used a powerful data-driven approach LCA to detect subgroups from a heterogeneous population, 2 examined the utility of a combined conceptualisation of resilience based on both cognitive trajectory and dementia status and 3 examined whether other protective factors not included in previous studies such as diet, contributed to resilience in APOE ɛ4 positive individuals. Summary Overall, our results showed that for APOE ɛ4 carriers who have not had a stroke, staying employed and increased self-reported mild physical activity rather than vigorous physical activity predicted cognitive resilience for men, while increased mental activity predicted cognitive resilience in women. Methods Participants The data were drawn from the Personality and Total Health Through Life PATH Study. APOE status Genotyping of the PATH sample has been described previously Memory Immediate recall was only assessed using one trial of the California Verbal Learning Test 35 in wave 1 of PATH. Cognitive impairment status MCI and dementia Cognitive impairment status was determined at wave 4 through clinical diagnosis. Protective factors Self-reported years of education including total years of primary, secondary, post-secondary, and vocational education was recorded at baseline along with mental activity, net positive social interactions, diet and physical activity. Medical Depression, anxiety, hypertension, diabetes, stroke, head injury, cholesterol medication and BMI were recorded at baseline. Lifestyle Smoking cigarettes per day and alcohol consumption drinks per week were self-reported at baseline. Analysis Group categorisation Latent class analysis LCA was used to classify individuals into outcome groups based on memory performance and cognitive impairment status. Comparisons between groups Group comparisons were completed using SPSS v References Liu, C. Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Rasmussen, K. Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Farrer, L. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar Huq, A. Article PubMed Google Scholar Kivipelto, M. Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Rovio, S. Military personnel often perform complex cognitive operations under unique conditions of intense stress. Impaired cognitive performance as a result of this stress may have serious implications for the success of military operations and the well-being of military service men and women, particularly in combat scenarios. Therefore, understanding the nature of the stress experienced by military personnel and the resilience of cognitive functioning to this stress is of great importance. This review synthesises the current state of the literature regarding cognitive resilience to psychological stress in tactical athletes. The experience of psychological stress in military personnel is considered through the lens of the Transactional Theory of stress, while offering contemporary updates and new insights. Models of the effects of stress on cognitive performance are then reviewed to highlight the complexity of this interaction before considering recent advancements in the preparation of military personnel for the enhancement of cognitive resilience. Several areas for future research are identified throughout the review, emphasising the need for the wider use of self-report measures and mixed methods approaches to better reflect the subjective experience of stress and its impact on the performance of cognitive operations. Stress and its impact on a range of cognitive processes continues to be a subject of intense scientific investigation. Ongoing research has led to the emergence of the concept of cognitive resilience , explaining the degree to which cognitive functions can withstand, or be resilient to, the effects of stress Staal et al. In military personnel, cognitively demanding tasks are regularly performed under stress, with a survey conducted by the U. To denote these demands, the term tactical athletes was reportedly offered by the former chief of staff of the US Army Hammermeister et al. Because of the prevalence of stress and the fact that the performance of cognitive tasks often carries significant consequences, ensuring and promoting cognitive resilience in military personnel is a high priority. Indeed, the development of mental skills training programs in military settings Cohn et al. Importantly, cognitive resources are required for self-regulation of effort, attention and emotional control, with real implications for the management of daily living demands and mental health Martin et al. In a previous review, we have demonstrated that military personnel are faced with a range of environmental stressors and that these stressors, including heat, cold and altitude, can have consequences for cognitive processes, including attention and working memory Martin et al. We have also synthesised the state-of-the-art evidence linking cognitive performance to physiological variations such as physical fatigue, sleep deprivation, nutrition and aerobic fitness Martin et al. This narrative review aims to extend upon this work by outlining the role of psychological factors in cognitive resilience. In the following text we review the concept of psychological stress and highlight how psychological processes of cognitive appraisal and coping can act to mitigate the effects of environmental stressors on cognitive performance in military personnel. While the effects of stress on cognition and operational performance have been the subject of several previous reviews see Staal, ; Kavanagh, ; Driskell et al. Recent developments in the enhancement of cognitive resilience are also considered against existing and well-established theoretical models, in an attempt to highlight gaps in knowledge and areas for future investigation. Although an all-encompassing definition remains elusive, in its use in the behavioural sciences, resilience is typically thought to involve two components: adversity and positive adaptation Luthar and Cicchetti, Accordingly, Luthar and Cicchetti , p. Resilience can also be framed as a trait, denoting certain personal attributes allowing an individual to positively adapt to demands Fletcher and Sarkar, In military settings, Mastroianni et al. In all cases, this interest in resilience as a personal strength represents a polar shift away from examining risk factors associated with problematic or dysfunctional outcomes Rutter, ; Fergus and Zimmerman, The concept of cognitive resilience has followed from this literature to describe the specific effects of stress on cognitive functioning. Cognitive resilience has been defined by Staal et al. This definition maintains the core characteristics of psychological resilience in adversity - or in this case, stress - and positive adaptation. There is a high degree of interest in cognitive resilience within the scientific literature, studying the resilience of a wide range of cognitive processes against the effects of stress in various populations. For example, Mujica-Parodi et al. In developmental neuropsychology, cognitive resilience has been used to explain individual differences in age-related declines in cognitive capacity Yaffe et al. In athletes, sustained attention, as assessed in a Stroop task, has been shown to be resilient to high levels of stress resulting from physical and academic demands Shields et al. The concept of cognitive resilience has also been applied to assess the effects of the unique stressors experienced by military personnel on cognitive functioning Morgan et al. Cognitive resilience is, therefore, important in many settings. Before delving deeper, however, an issue that is inherent in the examination and theoretical explanation of cognitive resilience is the definition of what constitutes stress. Below, we highlight the complexity of the concept of psychological stress before reviewing situations where cognitive resilience to psychological stress is challenged in military personnel. Historically, public and scientific interest in the concept of stress was borne out of what is now viewed as the stressors of war, particularly World War II Lazarus, Grinker and Spiegel wrote of the stress of war, with a focus on Air Force pilots. Military organisations were concerned with understanding the effects of stress on the performance of military personnel in battle, with the intention of using this information to inform the recruitment of those best able to maintain performance under stress Grinker and Spiegel, ; Lazarus and Folkman, In many ways, very little has changed, as evidenced by the military interest in the related concept of cognitive resilience described above. Importantly, however, the concept of stress permeated beyond the military setting and stress was recognised as relevant to the lives of civilians. For a comprehensive reflection on the history of stress research, we direct interested readers to Stress and Coping Lazarus, Below, we define psychological stress, drawing on the transactional theory of stress and coping, in order to contextualise the subsequent discussion of the effects of stress on cognition in military personnel. Stress, therefore, involved a subjective component that mediated the stressor-response relationship Lazarus and Folkman, Appraisal and coping were identified as the two cognitive processes mediating this person-environment transaction. According to Lazarus and Folkman , appraisal occurs in two main forms. This primary appraisal can be further classified into three forms. An irrelevant appraisal results from a transaction that is not deemed to be threatening. A benign-positive appraisal results from a person-environment transaction that is perceived as positive or expected to have a positive impact on well-being. Finally, stress appraisal results from a person-environment transaction that is perceived as negative or is expected to have a negative impact on well-being. Stress appraisal itself has three forms: harm, threat and challenge Lazarus and Folkman, ; Folkman et al. Challenge appraisal results from a person-environment transaction that has the potential to promote personal growth after a degree of personal difficulty or challenge. Indeed, each category of appraisal interacts to produce the degree of stress experienced by the individual and the coping approach utilised for any given transaction Lazarus and Folkman, Following the appraisal of the person-environment transaction, coping resources are mobilised to allow the individual to cope with the resulting stress. What is emphasised in this definition is that coping — at least in its use in the Transactional Theory — is not an automated response to a stressor but rather an effortful process that evolves to reflect the changing nature of the person-environment encounter Lazarus and Folkman, ; Folkman et al. The original Transactional Theory outlined two ways of coping: emotion- and problem-focussed coping Lazarus and Folkman, Emotion-focussed coping refers to coping strategies intended to regulate the emotional responses to the stressor, while problem-focussed coping strategies are used with the intention of impacting on or altering the stressor itself Lazarus and Folkman, However, Folkman later added a third category of coping, meaning-focussed coping. When stressors persist despite the activation of problem- and emotion-focussed coping, meaning-focussed coping strategies are initiated Folkman, This involves the use of beliefs, values and existential goals to find meaning in stressful encounters and to sustain coping efforts Folkman, This addition may prove to be particularly relevant to the management of stress in military settings, as discussed below. The two cognitive processes of coping and appraisal are thought to interact in a number of ways. First, the appraisal of the person-environment transaction can impact on the use and effectiveness of coping approaches Baum et al. Nonetheless, in cases where altering the transaction is difficult or impossible, emotion-focussed coping is more likely to be used. Appraisal and coping also interact through a process of reappraisal. Following coping efforts, a reappraisal of the changing person-environment transaction occurs Lazarus and Folkman, , adjusting the perceived stress and the coping strategy used. In summary then, the Transactional Theory suggests that the appraisal, coping and reappraisal of the person-environment transaction mediates the intensity of stress that is perceived. Despite the wide-spread adoption of the Transactional Theory in stress and coping research, numerous other categorisations of coping strategies have been formulated. For example, similar to the addition of meaning-based coping by Folkman , Billings and Moos added appraisal-focussed coping to emotion- and problem-focussed approaches. Skinner et al. problem-focussed and approach vs. avoidance classifications. Each family of root action tendencies then distill down to lower-order coping approaches such as help seeking, strategizing, procrastination and self-blame. This hierarchical model is now widely cited and has been applied in military settings Rossetto, Upon reviewing this research on psychological stress, we therefore highlight the importance of subjective perception in the experience of stress, arguing that a stressor causes stress only if is perceived as stressful Roesch et al. By outlining the role of cognitive appraisal, coping and reappraisal, this literature has expanded our understanding of the individual differences in the stress experienced as a result of a perceived or anticipated stressor. This understanding of stress provides a context through which we can begin to understand cognitive resilience as defined by Staal et al. We extend upon this discussion of the nature of stress and its impacts on cognition below, by discussing the psychological stress experienced in military settings before addressing the impact that this has on cognitive performance. Significant efforts have been made to profile the types of stressors that military personnel are exposed to. These efforts have identified a wide range of both military-specific and non-military-specific stressors that military personnel must overcome, or be resilient to, in order to maintain psychological and cognitive functioning. After an extensive investigation of the nature of the stressors experienced in military operations, Bartone et al. military personnel. These included isolation, ambiguity, powerlessness, boredom and danger. Later, Bartone added a sixth dimension of workload to account for the increasing demands placed on military personnel in the form of longer working hours and increased frequency of deployments. Encompassed within these six dimensions are a range of specific stressors reported by military personnel, including separation from family and friends isolation , the fluid nature of the mission ambiguity , an inability to influence changes occurring back home powerlessness , repetitive work boredom , the risk of injury or death danger and the high frequency of deployment workload ; see Bartone, for comprehensive review. We note here that the stressors identified were collected using self-report measures. As a result, they represent stressors that have been appraised as stressful, aligning with the definition of psychological stress provided by the Transactional Theory. From the dimensions identified in such analyses, much of the stress experienced by military personnel has parallels with the stressful experiences of civilian populations. For example, stress relating to workload extends well-beyond military settings, with workload considered a major contributor to occupational stress and burnout Jex, Similarly, boredom is a common complaint across a range of occupational domains Fisherl, Research in non-deployed military personnel certainly supports this argument, with work-related stressors such as changes in responsibilities, staffing and work hours being the most commonly reported sources of stress Pflanz, ; Pflanz and Sonnek, ; Pflanz and Ogle, It is clear from these findings that interventions aiming to reduce stress and its impact on the cognitive functioning of military personnel should not disregard the prevalence of these common occupational stressors. However, unique, military-specific stressors are also well recognised. These stressors often come in the form of combat stress, i. As such, combat stress may result from a range of stressors, including exposure to life threatening events or the injury and death of others Dekel et al. In a survey of U. However, reported exposure to these stressors was significantly reduced in those deployed to Afghanistan Hoge et al. Similar findings have been reported in an Australian military sample, with the threat of injury or death, seeing dead bodies, the death of a friend or co-worker, and causing death or injury to others, all listed as potentially traumatic events experienced by Australian military personnel on peacekeeping missions Hawthorne et al. At this time, more work is needed to extend beyond simply cataloguing the combat stressors faced by military personal by assessing the appraisal of these stressors. In order to collect such data, validated measurement tools of appraisal and coping e. It is likely that this approach will clarify whether these reported combat stressors, or potentially traumatic events, are appraised as stressful, an important distinction according to the Transactional Theory of psychological stress. The evolving nature of modern military operations presents as a challenge to profiling the types of stressors that cause psychological stress in military personnel. In their outline of the stressors of modern war, Mastroianni et al. In particular, they highlighted the shift from traditional warfare to the constant threat of unpredictable insurgent attack in current operations in Iraq. The health implications of this chronic psychological stress are perhaps most clearly represented by the high rates of post-traumatic stress disorder in military personnel returning from Iraq and Afghanistan Hoge et al. Whether similar deleterious effects are seen in cognitive functioning during deployment or, indeed, afterwards. Are yet to be determined, but there is accumulating evidence that — in the wider population - sufferers of PTSD do tend to also exhibit memory and attention deficits, associated with changes in functional brain activity Hayes et al. Advancements in technology have also produced significant changes in modern military combat. The increased use of unmanned aerial vehicles UAVs , in particular, represent this advancement in military technology Bone and Bolkcom, Although the use of UAVs removes the threat of physical harm to the pilot, recent research suggests that UAV pilots experience high levels of psychological stress Fitzsimmons and Sangha, ; Chappelle et al. In their detailed description of the experiences of UAV pilots, Fitzsimmons and Sangha highlighted the psychological closeness that is developed between the UAV pilot and their target — for example during extended observation of daily movements - and how this closeness may account for the psychological stress that operatives experience. The physical separation from the battlefield also presents as an issue for the psychological stress experienced by UAV pilots, with many commuting to a military base from their homes each day Armour and Ross, These factors, and likely many more, emphasise the importance of continuing the investigation into the psychological stress of modern warfare and its impact on cognitive performance. However, technological advancement, such as virtual reality, also offers an opportunity to combat the effects of stress on performance, a point discussed later in this review. The close intertwining of stress and cognitive performance is exemplified in the UAV concept, perhaps particularly because the physical demands, and physical threat are removed, and yet combat stress remains closely linked with, and dependent on, cognitive performance. Developments such as the proliferation of UAV warfare help to explain the renewed emphasis on cognitive resilience in tactical athletes. As outlined above, military personnel experience a range of both military-specific and non-military-specific psychological stress. Similarly, certain cognitive functions are of particular importance in military contexts. Investigations of cognition in military personnel have adopted a range of neurocognitive tools assessing memory, visuospatial integration, reaction time and executive functions Morgan et al. These cognitive domains are thought to be important for performance within a military context, for example, in navigating unfamiliar territory, executing orders while resisting distraction or reacting to unexpected threats. Executive functions of inhibition, shifting and updating appear to be especially and increasingly relevant to the military context Blacker et al. However, it should be noted that military personnel perform diverse tasks that engage a range of cognitive domains Blacker et al. Examinations of cognitive resilience, then, should adopt a tailored approach that consider the cognitive challenges and stressors specific to individual roles. In investigating the effects of stress on these military-relevant cognitive functions, researchers are faced with the challenge of inducing stress in ecologically valid ways. One approach has been to use stress inoculation training methods, also referred to as sustained operations SUSOPS training Vrijkotte et al. The field phase of Survival, Evasion, Resistance, and Escape SERE training Doran et al. In another assessment of the effects of SERE training, Harris et al. Interestingly, only simple reaction time was shown to be impaired following SERE training, while either no change or improved performance was observed in more complex cognitive tasks such as spatial processing. It is suggested that the allocation of effort towards these more complex cognitive operations can temporarily mask the deleterious effects of stress Harris et al. Beyond SERE training, Lieberman et al. Navy Seal training on cognitive performance. Similar stress-induced impairments in cognitive performance have been reported in paratrooper training Sharma et al. As these training environments are designed to mimic many of the characteristics of military operations, such as sleep loss, physical discomfort, perceived threat and intense physical activity, the reported decrements in cognitive performance may be representative of the expected changes occurring in active military operations. An important limitation of the research presented above, however, is the lack of subjective measurement of stress. Therefore, although some research suggests that military training environments and simulations induce psychological stress Kreuz et al. Attempts have been made to overcome this issue by reporting on changes in subjective perceptions of task load Taverniers et al. However, these measures do not directly assess psychological stress as defined by the Transactional Theory of stress Lazarus and Folkman, Future research should use established measures of both state and trait perceived stress, such as visual analogue scales Hellhammer and Schubert, and the Perceived Stress Scale Cohen et al. The inclusion of both subjective and objective measures of stress may help refine the protocols used for military training operations to better reflect and combat the apparent impact of subjective stress appraisal on cognitive functioning. Despite numerous attempts, the development of a comprehensive theoretical explanation of the effects of stress on cognition, has proven difficult. This difficulty is due to the complexity of both stress and cognition. For example, the source of stress and its intensity, controllability and duration have all been shown to influence the changes observed in cognitive functioning Sandi, The characteristics of the specific cognitive operation under investigation also influences the degree of resilience to stress Sandi, Theoretical explanations of cognitive resilience must account for the range of possible consequences resulting from these interactions between stress-related and cognition-related factors. It is beyond the scope of this review to fully account for the number of theories that have been presented to explain the effects of stress on cognition. Instead, in the following text we highlight a sample of the theoretical explanations that have been widely adopted, particularly in military psychology. It is not our intention here to argue for one particular theoretical position. Rather, we aim to identify common themes that permeate across theories, in order to provide a framework through which to consider the findings presented above regarding the extent to which cognitive functioning in military personnel can be made resilient to psychological stress. Hancock and Warm provide a model of the effects of stress on cognitive performance. This model, referred to as the Maximal Adaptability Model acknowledged that the cognitive task itself is a primary source of stress. In their dynamic model, Hancock and Warm argued that psychological and physiological adaptive mechanisms act to buffer the effects of stress on performance. Here, psychological adaptation refers to the allocation of attentional resources. Physiological adaptation refers to homeostatic regulatory functions that attempt to accommodate the effects of stressors Hancock and Warm, The Maximal Adaptability Model predicts that when stressors are minor, psychological and physiological adaptations can effectively buffer any disruptions to performance. However, as stressors progress to the extremes of hyper- or hypo-stress, limits of maximal psychological and physiological adaptability may be exceeded, resulting in dynamic instability. Given the high intensity and extended duration of the stressors associated with the military simulations described above, it is likely that limits of psychological and physiological maximal adaptability were exceeded. This would account for the observed impairments in cognitive functioning. Therefore, the dynamic model of Hancock and Warm may still serve as a theoretical explanation for the effects of stress on cognition in military settings. However, while physiological responses to stress inoculation training have been examined Taverniers et al. Two levels of control are proposed in this model. In well-learned tasks under conditions of low stress, performance is maintained by an automatic system of control that does not tax limited energetic resources. This response may involve the mobilisation of effort to protect task performance. However, much like attention in the work of Hancock and Warm , the Compensatory Control Model considers effort a limited resource Hockey, Therefore, while effort allocation may effectively, but temporarily, maintain primary task performance, prolonged or particularly intense stress may deplete resources to the point where performance decrements are observed Hockey, , as seen in the cognitive impairment resulting from military simulations. For example, peripheral task performance may be impaired through attentional tunnelling Kohn, ; Staal, and the use of less effortful cognitive strategies, such as heuristics Gigerenzer and Selten, , in non-primary tasks. In military settings, changes in mood Harris et al. According to the Compensatory Control Model, however, the allocation of effort is only one protection strategy that may be initiated by the supervisory controller. A second strategy, which avoids the aversive and costly mobilisation of effort, is to instead adjust performance targets Hockey, Although this passive coping strategy maintains energetic resources, task performance is impaired. Indeed, passive coping may, and often does, manifest as complete task disengagement Hockey, Given the often fixed and externally imposed nature of the performance targets in military combat settings, it is unclear whether passive coping strategies are possible for military personnel. Therefore, it is likely that in the stress inoculation training described above, and indeed during active combat, effort allocation may be the only protective strategy available to the supervisory controller. We encourage future research to consider whether, under the stress of combat, military personnel select to adjust their performance targets or instead sacrifice secondary tasks by allocating effort to primary targets. Furthering the emphasis on the protective reallocation of attentional reserves is the Attentional Control Theory Eysenck et al. It was argued that anxiety creates a state of self-preoccupation, drawing from limited attentional resources, which forces higher levels of effort to be allocated to maintain task performance. This increased allocation of effort may preserve performance quality effectiveness , but it does so at the expense of decreased processing efficiency. While Attentional Control Theory maintains this distinction between processing efficiency and performance effectiveness, it describes several important extensions Eysenck et al. Specifically, Attentional Control Theory provides a more nuanced explanation of attentional demands, suggesting that decrements in processing efficiency are due to an anxiety-induced shift in attention away from the pursuit of goals and towards salient stimuli. Further, according to Attentional Control Theory, anxiety is most likely to affect processing efficiency in tasks requiring the executive functions of inhibition and shifting, since these functions ensure attention is directed toward task-relevant stimuli. As described above, these cognitive operations are particularly relevant to a military context. Attentional Control Theory has been used to explain cognitive deficits resulting from anxiety and stress across a range of settings. Attentional Control Theory can also be used to explain decrements in shooting performance and increases in effort in simulated military operations designed to provoke anxiety Nibbeling et al. Such findings highlight the potential applications and practical utility of the predictions of Attentional Control Theory for tactical athletes in military settings. Common across all theories described above is the effortful allocation and reallocation of attention. This is thought to buffer the effects of stress on cognitive performance task effectiveness , underpinning the conceptualisation of cognitive resilience. However, in monitoring cognitive resilience, measures should extend beyond task performance to also consider processing efficiency. This can be achieved by measuring subjective workload or perceived effort to determine the potential that effort allocation is protecting performance from the effects of stress. Uncovering regular, compensatory allocation of effort to sustain performance under stress may help to 1 detect potential threats to cognition before performance is degraded and 2 avoid cognitive and emotional burnout in military personnel. An understanding of the psychological stress experienced in military personnel and the impact of this stress on cognitive functioning offers avenues for enhancing cognitive resilience. However, the limits of cognitive resilience are bounded by two key considerations. First, stress is an inescapable and, therefore, inevitable part of life Lazarus and Folkman, Second, cognitive performance is rarely immune to the effects of stress Kavanagh, Despite these constraints, cognitive resilience can be enhanced see below and individual differences do exist, both in the psychological stress response Parkes, and cognitive resilience to stress Staal et al. Indeed, the Transactional Theory and Maximal Adaptability Model have been used to develop comprehensive assessment tools, such as the Readiness Assessment and Monitoring System Cosenzo et al. The capacity to train or enhance cognitive resilience also has obvious practical implications in military settings. A review by Kavanagh considered two points of moderation, where various factors can intervene in the effects of stress on performance. The first point of intervention type 1 moderators , includes factors that moderate the stress that results from the presentation of a stressor Kavanagh, While Kavanagh was concerned with physiological responses to stressors, this first point of intervention also applies in psychological stress. Specifically, type 1 moderators can be seen as equivalent to the person-environment transaction described by Lazarus and Folkman That is, once stress is experienced, what are the factors that moderate its effects on performance? Despite the focus on the physiological stress response, this two-point moderation model provides a useful heuristic for the consideration of interventions to enhance cognitive resilience in the military. Several methods of enhancing cognitive resilience in military personnel were reviewed by Staal et al. However, since that review, considerable gains have been made in the development of programs that aim to enhance cognitive resilience in military personnel. Mindfulness-based interventions, in particular, have proven to be especially effective in enhancing cognitive resilience. For example, Jha and colleagues Jha et al. Mindfulness interventions can act to reduce the psychological stress response Baer et al. In fact, Johnson et al. As a type 2 moderator, mindfulness interventions have been shown to improve performance in a range of cognitive operations Jha et al. Physical training, particularly in tasks requiring the regulation of effort and pacing i. Similarly, Virtual Reality VR technology has been used in military training environments to train cognitive resilience to stress. Most commonly, VR technology has been paired with cognitive-behavioural therapy as a tool to gradually and safely expose military personnel suffering from PTSD to anxiety provoking stimuli so that therapeutic cognitive reorientation can take place Rizzo et al. Adopting the principles of stress inoculation training programs outlined above see also Meichenbaum, , VR technology has been used to present stress-inducing virtual scenarios to encourage adaptive responses in military personnel Pallavicini et al. This technology has also allowed for more realistic and therefore, ecologically valid tools for assessing cognitive operations Parsons and Rizzo, and has been shown to enhance military operational performance Wiederhold and Wiederhold, Therefore, by acting on stress appraisal and reducing the impact of stress on performance, VR-based stress inoculation training can influence cognitive resilience at both points of moderation proposed by Kavanagh With such wide-ranging applications, VR presents as an exciting opportunity to enhance the psychological and cognitive readiness of military personnel. However, while physiological stress markers have been routinely monitored during VR-based stress inoculation training Rizzo et al. It has recently been suggested that a return to past approaches is needed to combat the risk-averse nature of current military training protocols Nindl et al. While an overly risk-averse direction may ultimately reduce the combat readiness of military personnel, continual refinement of training protocols is necessary to acknowledge the changing nature of the stressors faced by military personnel and the many advancements made in deployment preparation. Promising areas of research into the psychological preparation of military personnel for modern combat are wide-ranging, certainly extending beyond the examples provided here. Given its importance in military operations, further exploration of methods to promote cognitive resilience, grounded in the theoretical models outlined above, is encouraged. In the modern context, online and app-based interventions may also be adopted to support the monitoring of stressful stimuli, changes to stress appraisal, and also optimal coping strategies, with a view to shifting the scientific support closer towards the moments and locations where the stress is experienced. The stressors faced by military personnel are diverse, ranging from boredom to the threat of injury and death. Advancements in technology and the nature of war mean that these stressors are also constantly evolving. It is, therefore, difficult to profile the stress experienced by military personnel in modern military operations and to determine the impact of this stress on cognitive performance. However, despite the diversity and evolution of these stressors, this review highlights that existing theoretical models remain relevant to understanding cognitive resilience in military settings. The Transactional Theory emphasises the importance of appraisal and coping for the subjective experience of stress. Attentional Control Theory and the compensatory control and maximal adaptability models explain how stress may impact on cognitive functioning by threatening limited reserves of effort and attention. Importantly, these existing theoretical perspectives emphasise that stress-induced changes in cognition may not initially be detected through decrements in performance, but instead through decreased efficiency. Further incorporation of these models into military settings will provide a platform upon which to advance our understanding of cognitive resilience to psychological stress. Several areas for future investigation have been identified throughout this review. Taken together, these recommendations identify that while the stressors faced by military personnel have been well-documented, more work is needed to determine how these stressors are appraised. This will better inform our understanding of the lived, subjective experience of stress in military personnel. It is only then that we can begin to appreciate the complexity of cognitive resilience in military settings and better prepare military personnel for the realities of modern warfare. AF led in the planning, research, and drafting of this paper. RK liaised with the key stakeholders, agreed the necessity of the review, and reviewed and edited the drafts during the development of the paper. RK and AF worked together to plan the paper at the design stage. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version. The funding source was not involved in the preparation of the article for publication. The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher. Armour, C. The health and well-being of military drone operators and intelligence analysts: a systematic review. doi: CrossRef Full Text Google Scholar. Arnold, S. Cellular, synaptic, and biochemical features of resilient cognition in Alzheimer's disease. Aging 34, — PubMed Abstract CrossRef Full Text Google Scholar. Baer, R. Weekly change in mindfulness and perceived stress in a mindfulness-based stress reduction program. Bartone, P. Resilience under military operational stress: can leaders influence hardiness? Dimensions of psychological stress in peacekeeping operations. Baum, A. Coping with victimization by technological disaster. Issues 39, — Ben-Avraham, R. Feasibility and preliminary effectiveness of mobile cognitive control training during basic combat training in the military. Bequette, B. Physical and cognitive load effects due to a powered lower-body exoskeleton. Factors 62, — Biggs, A. Cognitive training can reduce civilian casualties in a simulated shooting environment. Billings, A. Psychosocial theory and research on depression: an integrative framework and review. Binsch, O. Testing the applicability of a virtual reality simulation platform for stress training of first responders. Blacker, K. Cognitive training for military application: a review of the literature and practical guide. Bone, E. Unmanned Aerial V ehicles: Background and Issues for Congress. Library Of Congress Washington Dc Congressional Research service. Google Scholar. Bray, R. Retrieved from Research Triangle Park, NC. Buckwalter, J. |

| Add new comment | Specifically, type 1 moderators can be seen as equivalent to the person-environment transaction described by Lazarus and Folkman That is, once stress is experienced, what are the factors that moderate its effects on performance? Despite the focus on the physiological stress response, this two-point moderation model provides a useful heuristic for the consideration of interventions to enhance cognitive resilience in the military. Several methods of enhancing cognitive resilience in military personnel were reviewed by Staal et al. However, since that review, considerable gains have been made in the development of programs that aim to enhance cognitive resilience in military personnel. Mindfulness-based interventions, in particular, have proven to be especially effective in enhancing cognitive resilience. For example, Jha and colleagues Jha et al. Mindfulness interventions can act to reduce the psychological stress response Baer et al. In fact, Johnson et al. As a type 2 moderator, mindfulness interventions have been shown to improve performance in a range of cognitive operations Jha et al. Physical training, particularly in tasks requiring the regulation of effort and pacing i. Similarly, Virtual Reality VR technology has been used in military training environments to train cognitive resilience to stress. Most commonly, VR technology has been paired with cognitive-behavioural therapy as a tool to gradually and safely expose military personnel suffering from PTSD to anxiety provoking stimuli so that therapeutic cognitive reorientation can take place Rizzo et al. Adopting the principles of stress inoculation training programs outlined above see also Meichenbaum, , VR technology has been used to present stress-inducing virtual scenarios to encourage adaptive responses in military personnel Pallavicini et al. This technology has also allowed for more realistic and therefore, ecologically valid tools for assessing cognitive operations Parsons and Rizzo, and has been shown to enhance military operational performance Wiederhold and Wiederhold, Therefore, by acting on stress appraisal and reducing the impact of stress on performance, VR-based stress inoculation training can influence cognitive resilience at both points of moderation proposed by Kavanagh With such wide-ranging applications, VR presents as an exciting opportunity to enhance the psychological and cognitive readiness of military personnel. However, while physiological stress markers have been routinely monitored during VR-based stress inoculation training Rizzo et al. It has recently been suggested that a return to past approaches is needed to combat the risk-averse nature of current military training protocols Nindl et al. While an overly risk-averse direction may ultimately reduce the combat readiness of military personnel, continual refinement of training protocols is necessary to acknowledge the changing nature of the stressors faced by military personnel and the many advancements made in deployment preparation. Promising areas of research into the psychological preparation of military personnel for modern combat are wide-ranging, certainly extending beyond the examples provided here. Given its importance in military operations, further exploration of methods to promote cognitive resilience, grounded in the theoretical models outlined above, is encouraged. In the modern context, online and app-based interventions may also be adopted to support the monitoring of stressful stimuli, changes to stress appraisal, and also optimal coping strategies, with a view to shifting the scientific support closer towards the moments and locations where the stress is experienced. The stressors faced by military personnel are diverse, ranging from boredom to the threat of injury and death. Advancements in technology and the nature of war mean that these stressors are also constantly evolving. It is, therefore, difficult to profile the stress experienced by military personnel in modern military operations and to determine the impact of this stress on cognitive performance. However, despite the diversity and evolution of these stressors, this review highlights that existing theoretical models remain relevant to understanding cognitive resilience in military settings. The Transactional Theory emphasises the importance of appraisal and coping for the subjective experience of stress. Attentional Control Theory and the compensatory control and maximal adaptability models explain how stress may impact on cognitive functioning by threatening limited reserves of effort and attention. Importantly, these existing theoretical perspectives emphasise that stress-induced changes in cognition may not initially be detected through decrements in performance, but instead through decreased efficiency. Further incorporation of these models into military settings will provide a platform upon which to advance our understanding of cognitive resilience to psychological stress. Several areas for future investigation have been identified throughout this review. Taken together, these recommendations identify that while the stressors faced by military personnel have been well-documented, more work is needed to determine how these stressors are appraised. This will better inform our understanding of the lived, subjective experience of stress in military personnel. It is only then that we can begin to appreciate the complexity of cognitive resilience in military settings and better prepare military personnel for the realities of modern warfare. AF led in the planning, research, and drafting of this paper. RK liaised with the key stakeholders, agreed the necessity of the review, and reviewed and edited the drafts during the development of the paper. RK and AF worked together to plan the paper at the design stage. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version. The funding source was not involved in the preparation of the article for publication. The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher. Armour, C. The health and well-being of military drone operators and intelligence analysts: a systematic review. doi: CrossRef Full Text Google Scholar. Arnold, S. Cellular, synaptic, and biochemical features of resilient cognition in Alzheimer's disease. Aging 34, — PubMed Abstract CrossRef Full Text Google Scholar. Baer, R. Weekly change in mindfulness and perceived stress in a mindfulness-based stress reduction program. Bartone, P. Resilience under military operational stress: can leaders influence hardiness? Dimensions of psychological stress in peacekeeping operations. Baum, A. Coping with victimization by technological disaster. Issues 39, — Ben-Avraham, R. Feasibility and preliminary effectiveness of mobile cognitive control training during basic combat training in the military. Bequette, B. Physical and cognitive load effects due to a powered lower-body exoskeleton. Factors 62, — Biggs, A. Cognitive training can reduce civilian casualties in a simulated shooting environment. Billings, A. Psychosocial theory and research on depression: an integrative framework and review. Binsch, O. Testing the applicability of a virtual reality simulation platform for stress training of first responders. Blacker, K. Cognitive training for military application: a review of the literature and practical guide. Bone, E. Unmanned Aerial V ehicles: Background and Issues for Congress. Library Of Congress Washington Dc Congressional Research service. Google Scholar. Bray, R. Retrieved from Research Triangle Park, NC. Buckwalter, J. Strive: Stress resilience in virtual environments. Paper presented at the Virtual Reality Short Papers and Posters VRW , IEEE, Orange County, CA, USA. Casey, G. Comprehensive soldier fitness: a vision for psychological resilience in the US Army. Chapa, J. Remotely piloted aircraft, risk, and killing as sacrifice: the cost of remote warfare. Military Ethics 16, — Chappelle, W. Cohen, S. A global measure of perceived stress. Health Soc. Cohn, A. Resilience training in the Australian defence force. InPsych: the Bulletin of the Australian Psychological Society. Cosenzo, K. Ready or not: enhancing operational effectiveness through use of readiness measures. Space Environ. Dekel, R. Combat exposure, wartime performance, and long-term adjustment among combatants. Doran, A. Kennedy, C. New York, NY: The Guilford Press , Driskell, J. Does stress lead to a loss of team perspective? Group Dyn. Theory Res. Decision Making and Performance Under Stress Military Life: The Psychology of Serving in Peace and Combat: Military Performance. Westport, CT: Praeger Security International, — Eysenck, M. Anxiety and performance: the processing efficiency theory. Anxiety and cognitive performance: attentional control theory. Emotion 7, — Fergus, S. Adolescent resilience: a framework for understanding healthy development in the face of risk. Public Health 26, — Filipas, L. A 4-week endurance training program improves tolerance to mental exertion in untrained individuals. Sport 23, — Fisherl, C. Boredom at work: a neglected concept. Fitzsimmons, S. Killing in high definition. Technology 12, — Fletcher, D. A grounded theory of psychological resilience in Olympic champions. Sport Exerc. Folkman, S. Personal control and stress and coping processes: a theoretical analysis. Positive psychological states and coping with severe stress. The case for positive emotions in the stress process. Anxiety Stress Coping 21, 3— Dynamics of a stressful encounter: cognitive appraisal, coping, and encounter outcomes. Appraisal, coping, health status, and psychological symptoms. Positive affect and the other side of coping. Gigerenzer, G. London, England: MIT Press, Grier, R. Military cognitive readiness at the operational and strategic levels: a theoretical model for measurement development. Making 6, — Grinker, R. Men Under Stress. Philadelphia, PA: Blakiston. Hammermeister, J. Military applications of performance psychology methods and techniques: an overview of practice and research. Hancock, P. A dynamic model of stress and sustained attention. Factors 31, — Hansen, A. Relationship between heart rate variability and cognitive function during threat of shock. Stress Coping 22, 77— Harris, W. Information processing changes following extended stress. Hawthorne, G. Australian Peacekeepers: Long-Term Mental Health Status, Health Service Use, and Quality of Life - Technical Report. Australia: Department of Psychiatry, University of Melbourne. Hayes, J. Emotion and cognition interactions in PTSD: a review of neurocognitive and neuroimaging studies. Hellhammer, J. The physiological response to Trier social stress test relates to subjective measures of stress during but not before or after the test. Psychoneuroendocrinology 37, — Hockey, G. Compensatory control in the regulation of human performance under stress and high workload: a cognitive-energetical framework. Hoge, C. Combat duty in Iraq and Afghanistan, mental health problems, and barriers to care. Jex, S. Stress and Job Performance: Theory, Research, and Implications for Managerial Practice. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Ltd. Jha, A. Mindfulness training modifies subsystems of attention. PLoS One e Practice is protective: mindfulness training promotes cognitive resilience in high-stress cohorts. Mindfulness 8, 46— Examining the protective effects of mindfulness training on working memory capacity and affective experience. Emotion 10, 54— Short-form mindfulness training protects against working memory degradation over high-demand intervals. Johnson, D. Modifying resilience mechanisms in at-risk individuals: a controlled study of mindfulness training in marines preparing for deployment. Kahneman, D. Attention and Effort. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall Inc. Kavanagh, J.. Stress and Performance A Review of the Literature and its Applicability to the Military. html Accessed June 20, Keinan, G. Training for task performance under stress: the effectiveness of phased training methods. They reasoned that comparing APOE ɛ4 carriers with the entire cohort would yield a more representative classification of resilience than just basing their definition on APOE ɛ4 carriers alone. However, subsequent analyses post-classification focused only on APOE ɛ4 carriers as this was our demographic of interest. Group comparisons were completed using SPSS v Logistic regression was used to examine the factors that predicted resilience. Predictors were separated into 3 models including: 1 protective factors, 2 genetic and demographics, and 3 medical and lifestyle factors. Model 1 protective factors included years of education, MIND diet score, physical activity, net positive social exchanges and cognitive activity. Model 2 genetics and demographics included APOE ɛ4 allele status, age, partnered and employment status. Model 3 medical and lifestyle included hypertension, diabetes, heart problems, head injury, BMI, taking medication for cholesterol, anxiety, depression, number of cigarettes a day and number of drinks a week. Results were post-LCA were stratified by gender. PATH is not a publicly available dataset and it is not possible to gain access to the data without developing a collaboration with a PATH investigator. Researchers can access the data through an approval process by submitting a proposal to the PATH committee. Liu, C. Apolipoprotein E and Alzheimer disease: Risk, mechanisms and therapy. Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar. Rasmussen, K. Absolute year risk of dementia by age, sex and APOE genotype: A population-based cohort study. CMAJ , E—E Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar. Farrer, L. et al. Effects of age, sex, and ethnicity on the association between apolipoprotein E genotype and Alzheimer disease: A meta-analysis. JAMA , — Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar. Huq, A. Alzheimers Dement. Article PubMed Google Scholar. Kivipelto, M. Apolipoprotein E ɛ4 magnifies lifestyle risks for dementia: A population-based study. Rovio, S. Lancet Neurol. Livingston, G. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: report of the Lancet Commission. Lancet , — Anstey, K. A systematic review of meta-analyses that evaluate risk factors for dementia to evaluate the quantity, quality, and global representativeness of evidence. Alzheimers Dis. Stern, Y. Brain reserve, cognitive reserve, compensation, and maintenance: Operationalization, validity, and mechanisms of cognitive resilience. Aging 83 , — Arenaza-Urquijo, E. Resistance vs resilience to Alzheimer disease: Clarifying terminology for preclinical studies. Neurology 90 , — Resilience in midlife and aging. In Handbook of the Psychology of Aging — Elsevier, Chapter Google Scholar. Kaup, A. Cognitive resilience to apolipoprotein E ε4: Contributing factors in black and white older adults. JAMA Neurol. Ferrari, C. How can elderly apolipoprotein E ε4 carriers remain free from dementia?. Aging 34 , 13—21 Hayden, K. Cognitive resilience among APOE ε4 carriers in the oldest old. Psychiatry 34 , — McDermott, K. B Psychol. PubMed Google Scholar. Vermunt, J. Latent class cluster analysis. Latent Class Anal. Google Scholar. Association of sex differences in dementia risk factors with sex differences in memory decline in a population-based cohort spanning 20—76 years. Article Google Scholar. Nebel, R. McFall, G. Alzheimer Res. Thibeau, S. Physical activity and mobility differentially predict nondemented executive function trajectories: Do sex and APOE Moderate These Associations?. Gerontology 65 , — Mielke, M. Masyn, K. Book Google Scholar. Blondell, S. Does physical activity prevent cognitive decline and dementia? BMC Public Health 14 , 1—12 Dumuid, D. Does APOE ɛ4 status change how hour time-use composition is associated with cognitive function? An exploratory analysis among middle-to-older adults. Article CAS Google Scholar. Quinlan, C. The accuracy of self-reported physical activity questionnaires varies with sex and body mass index. PLoS One 16 , e Mayman, N. Sex differences in post-stroke depression in the elderly. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Poynter, B. Sex differences in the prevalence of post-stroke depression: A systematic review. Psychosomatics 50 , — Alvares Pereira, G. Cognitive reserve and brain maintenance in aging and dementia: An integrative review. Adult 29 , — Cheng, S. Cognitive reserve and the prevention of dementia: The role of physical and cognitive activities. Psychiatry Rep. Müller, S. Casaletto, K. Late-life physical and cognitive activities independently contribute to brain and cognitive resilience. Cohort profile update: The PATH through life project. Cohort profile: The PATH through life project. Jorm, A. APOE genotype and cognitive functioning in a large age-stratified population sample. Neuropsychology 21 , 1—8 Delis, D. California Verbal Learning Test Psychological Corporation, Eramudugolla, R. Evaluation of a research diagnostic algorithm for DSM-5 neurocognitive disorders in a population-based cohort of older adults. Alzheimers Res. Winblad, B. Mild cognitive impairment—Beyond controversies, towards a consensus: Report of the International Working Group on Mild Cognitive Impairment. Parslow, R. An instrument to measure engagement in life: Factor analysis and associations with sociodemographic, health and cognition measures. Gerontology 52 , — Schuster, T. Supportive interactions, negative interactions, and depressed mood. Community Psychol. Hosking, D. MIND not Mediterranean diet related to year incidence of cognitive impairment in an Australian longitudinal cohort study. Morris, M. MIND diet slows cognitive decline with aging. Civil Service Occupation Health Service. Stress and Health Study, Health Survey Questionnaire, Department of Epidemiology and Public Health, Goldberg, D. Detecting anxiety and depression in general medical settings. BMJ , — Download references. We thank the study participants, PATH interviewers, project team, and Chief Investigators Tony Jorm, Helen Christensen, Bryan Rogers, Keith Dear, Simon Easteal, Peter Butterworth, Andrew McKinnon. The work was supported by the Australian Research Council grant number FL to LZ and KJA; Canadian Consortium on Neurodegeneration in Aging, Alberta Innovates and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research CIHR grant number to RAD; and Alberta Innovates Data-enabled Innovation Graduate Scholarship to SMD. The PATH cohort study was funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council NHMRC grant numbers , , , Safe Work Australia, NHMRC Dementia Collaborative Research Centre and Australian Research Council grant numbers FT, DP, CE Do you work with or have a desire to work with Service Members, African Americans or Veterans who struggle with overcoming adversity? Would you like to be better equipped to help them overcome adversity? Would you like to learn the latest strategies for building personal resilience in the clinical setting? Would you like to develop resilience skills that will enable you to avoid burnout and excel professionally? |