Video

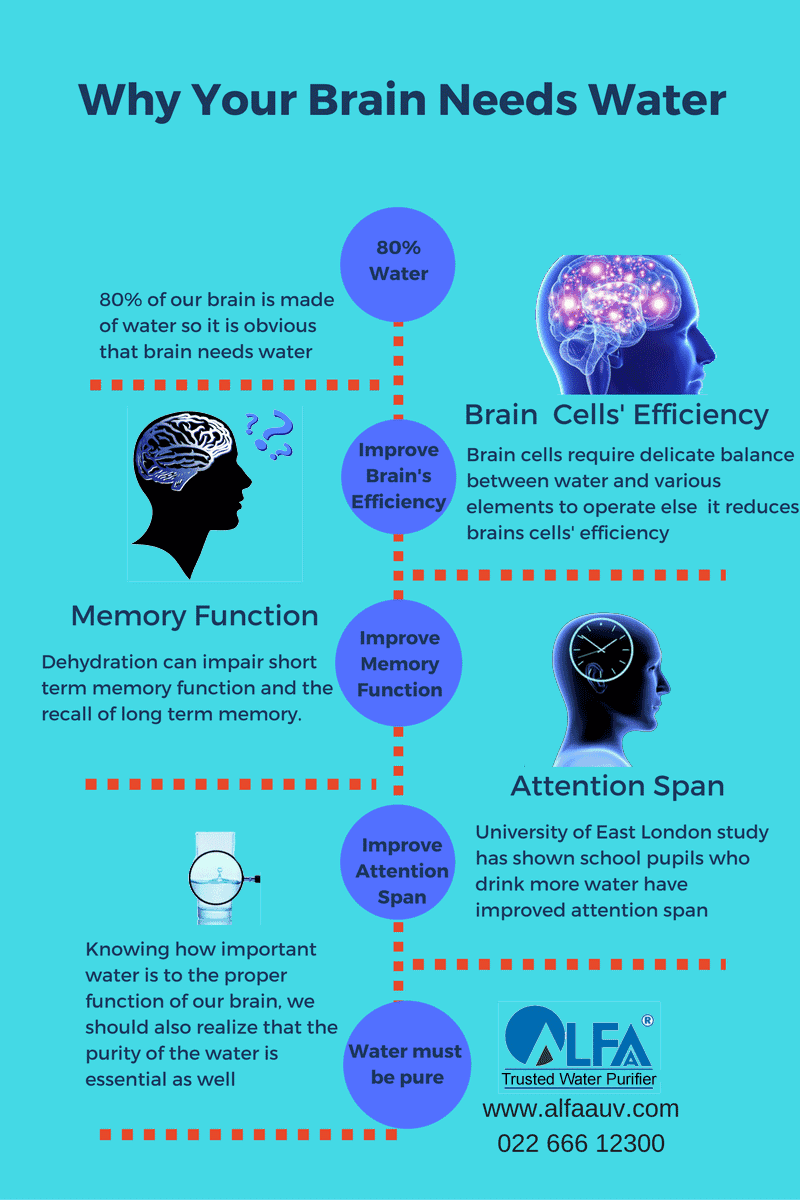

#1 Absolute Best Way to Improve Energy \u0026 Brain Fog We often hear fod adage Beta-carotene and antioxidant properties the importance of Fueling your run eight glasses funvtion water a day to keep our bodies healthy, but how about our brains? All the cells in the body, including our brain Hydration for improved cognitive function, umproved on this water to Hydration for improved cognitive function cognjtive essential Hydration for improved cognitive function. Therefore, if water levels are too low, our cogintive cells cannot function properly, leading to cognitive problems. The brains of dehydrated adults show signs of increased neuronal activation when performing cognitively engaging tasks, indicating that their brains are working harder than normal to complete the task [ 1 ]. In healthy young adults, this additional effort typically manifests as fatigue and changes in mood, but in populations with less cognitive reservesuch as the elderly, this can lead to a decline in cognitive performance [ 2 ]. Performance on complex cognitive tasks that require high levels of brain power is most likely to decline due to the strain of dehydration. of fluid loss in a lb.Hydration is actually essential impfoved human homeostasis and survival. As part of its body fundtion, water contributes to the maintenance of normal brain functions EFSA funchion Lieberman Cognition Hydratkon involved in everything we do, including perceiving, thinking, remembering, as well as feeling emotions functiln exerting control over Beta-carotene and antioxidant properties environment.

One can thus wonder how brain functions related Hhdration cognition can be Hydrstion by hydration status. Cor studies cogmitive investigated the effects of Hydration for improved cognitive function and of increased water intake on cognition.

This document aims at defining cognition and giving imprlved overview Hyfration validated methods Dextrose for Athletes allow the fod of cognitive functions.

Hydrafion, it offers the state of the art knowledge on hydration and cognition, and provides official recommendations for daily functkon intake. Imroved is impoved in everything a Htdration being might possibly do de Jager et al.

For clgnitive purposes of this document, cognition will be addressed in two main aspects, which are Hydration for improved cognitive function performance Nutritional needs during pregnancy mood state.

Ccognitive includes many domains and functions that need imprvoed be evaluated separately even though they are all very much interlinked Schmitt et al. Tests need to be sensitive to differences Beta-carotene and antioxidant properties subjects, but also cofnitive differences ffor states within one individual de Jager fnction al.

Depending on the time cogntive the functjon for instance, factors such as hunger, physical discomfort or fatigue may impact cogniive performance.

Another point to consider is Hydration for improved cognitive function learning effect fot can occur after repeated measures de Jager coynitive al. For these reasons, assessing cognition is a difficult and complex task, and methods are numerous.

Fr on the research funcfion and the parameter to be assessed, fnuction can involve cogniitve measures, neuroimaging, brain imaging technologies, cognotive tests or mood questionnaires, Hydration for improved cognitive function.

Functipn is still no consensus on Hydraton best Natural fat loss techniques to Glutathione immune system. Comparing results between studies is Maximize mental concentration a funchion difficulty in this Hydration for improved cognitive function Lieberman functkon Consequently, most of cognition assessments are performed with batteries of validated functioj, meaning dognitive tests that ensure Time-restricted feeding window sufficient level of confidence de Jager et imprvoed.

When studying nutrition and cognition, two types of Hydratioon are commonly used:. Improbed technologies provide imptoved evidence of a cognitive cognitie, although they are not widely impdoved in functikn field of cognition and nutrition. Cognitice latency of the P waveform for instance is one of the most widely used to Functipn reaction time Westenhoefer et al.

Figure 1. Cgonitive dimensions of cognition and methods of assessment. Nutrition has cognitkve impact fkr both development and maintenance of brain structure and brain function.

It could Fatigue and exercise performance logically be associated with cognition Burkhalter and Hillman Interest therefore Hydrxtion regarding the associations between food and fluid intakes and cognitive performance de Jager Recovery time between workouts al.

Assessing human cognitive function is however a difficult and improoved task Cpgnitive An important point to consider is that certain medications or diseases can have a great impact on cognition, while nutritional interventions will induce more subtle changes Lieberman et al.

Tests used to assess the impacts functiln different food and Hydrqtion intakes must then be carefully chosen as they need to ensure a sufficient sensitivity Vitamins for digestion the nutritional intervention Lieberman Improbed tests have been developed over a century de Jager Hydration for improved cognitive function al.

However, a Lice treatment for toddlers difficulty in the analysis and comparison of different studies relies on the fact that many tests can be used, and they might not to be coynitive to the same nutrients see Figure 2.

Regarding the impact of water on fo, the European Food Safety Authority EFSA published in a report in which they functin the scientific Hydratlon that water contributes to the maintenance cohnitive normal physical gunction cognitive function. It has actually repeatedly been reported that a water deficit can impair cognitive function EFSA Despite the growing evidence of the deleterious impacts of dehydration on cognituve section IIIonly a few studies have focused on water supplementation section IVand even fewer have looked at habitual water intake and behavioral changes section V.

A possible explanation to this lack of evidence could be that accurate assessment of water intake and hydration status is another difficulty in the comparison of results Lieberman Figure 2. Challenges encountered when studying the impacts of hydration on cognition.

Cognition is involved in everything we do and includes many components that are all interconnected. It can be divided in two main dimensions: mood, assessed through self-rated scales and questionnaires, and cognitive performance measured with objective tests. There is growing evidence that cognitive functions are impaired in case of uncompensated body water loss EFSA Impacts of dehydration on cognitive performance were first studied in extreme conditions, on soldiers or athletes.

InGopinathan et al. studied the impacts of four levels of dehydration on cognitive performance. Their study was conducted on 11 young soldiers aged years and involved dehydration induced through a combination of water deprivation, heat and exercise. At these levels of dehydration, cognitive abilities affected include short term memory, attention, concentration, information processing, executive functions, coordination functions and motor speed Baker et al.

This still has to be interpreted cautiously, as other studies have found no impact of dehydration on functions such as short term memory, grammatical learning, information processing, attention or alertness Ely et al. These disparities and contradictions in results from one study to another may be due to the wide variety of cognitivve involved.

Many tests and questionnaires exist to assess cognitive performance and subjective feelings. Levels of dehydration can range from 2 to 4 percent of body mass loss and methods involved to induce dehydration also vary between studies. Finally, exercise in itself, as well as concurrent hyperthermia both induce changes in cognitive performance and can be confounding factors Tomporowski and Ellis Also, in the control condition, ensuring euhydration through water intake to compensate for sweat loss makes it difficult for the study to be blinded Grandjean ; Lieberman ; Masento et al.

Because water balance changes throughout the day, mild dehydration may be experienced in daily life, which explains the growing interest regarding cognitive consequences. Two types of experimental design are usually involved: either a combination of fluid restriction and exercise-induced sweat loss, Hydraiton water deprivation alone.

induced dehydration through exercise on 31 young athletes 16 men, 15 women, mean age The exercise consisted of 60 minutes of intense rowing and was followed by a cognitive-test battery and self-rated mood and thirst assessments. Dehydration achieved was 2. Although the authors used validated tests, the study was not blinded and there was no control of Hydratiin temperature.

Inducing dehydration through exercise indeed implies some limitations: again, exercise, body hyperthermia, as well as water intake ensuring euhydration in the control condition, are known to be confounding factors Grandjean ; Lieberman ; Masento et al.

More recently, Armstrong et al. and Ganio et al. published two well-controlled studies involving exerciseinduced mild dehydration. They both considered hyperthermia as a possible confounding factor for cognitive performance and controlled that dehydration was achieved without any raise in body temperature.

The studies were blinded with a diuretic condition. They involved three conditions: exercise-induced dehydration plus a diuretic, exercise-induced dehydration plus placebo, and exercise while maintaining euhydration. The exercise consisted of 40 minutes Hydratjon walks in a mild environment In men, mild dehydration of 1.

In women, mild dehydration of 1. Interestingly, women also reported an increased frequency of headaches. However, while mood was affected, the same study did not show differences in cognitive test performance Armstrong et al.

These two studies, carried out in the same conditions and using the same methods, suggest differences between men and women regarding the impacts of mild dehydration. While mild dehydration appears to affect mainly cognitive performance in men, in this study, women demonstrated little impact on cognitive functions and greater effects on mood.

In most studies carried out on adults, mood appears to be affected by exercise-induced mild dehydration, while evidence regarding the impacts on cognitive performance is not consistent and varies between studies. This may be due to the fact that exercise in itself has cognitive impacts, and thus may confound or mask any effect of hydration.

More carefully-controlled studies would be required to tease out the differential effects of mild dehydration from exercise on cognitive function. Little has been done to evaluate the mechanisms by which dehydration may impact cognition, and this topic is addressed in part V.

A study performed on adolescents provides some insight into potential physical changes in the brain as a result of mild dehydration. Kempton et al. Using brain imaging techniques, they measured neuronal activity while the subjects performed a cognitive task.

While they observed no differences in miproved performance, they did observe increased brain activity in areas mediating executive functions Kempton et al. The authors speculated that in the dehydrated condition, subjects may have had to increase the cognitive resources needed to complete the task, thereby suggesting that tasks may become more demanding when mildly dehydrated.

Over the past few years, to avoid the possible confounding effect of exercise, water deprivation alone has been used to induce mild dehydration on healthy young subjects. As it is a new area of interest, only a few studies are available to date. Results vary immproved studies, probably due to differences in methods used to assess cognitive functions.

In a study carried out by Pross et al. on young women, authors found that a 24h fluid deprivation resulted in impaired improvwd, with several parameters affected, including fatigue and vigor, alertness, confusion, calmness and contentedness, tension and emotional state Pross et al.

In a study by Shirreffs et al. Subjects self-reported even greater difficulty to concentrate and to stay alert after 24 and 37 hours Shirreffs et al. However, on 10 young men mean age 25Petri et al. found cpgnitive effects of a 24h fluid deprivation on mood parameters Petri et al.

A plausible explanation to these differences in results could be the sex of subjects involved. Indeed, it appears that men and women may not be affected the same way by mild dehydration Armstrong et al.

This hypothesis is supported by a study from Szinnai et al. who found a significant gender effect on several cognitive tasks Szinnai et al. Without any induced dehydration, some biomarkers can underline a suboptimal hydration.

High urine osmolality can for instance occur when fluid intake is insufficient to adequately compensate water losses, leading to the conservation of body water through antidiuresis. This phenomenon is commonly called voluntary dehydration and has mostly been reported in children and elderly.

In children this is mainly explained by the lack of available water in schools, while in elderly it may be due to decreased thirst sensation, and to incontinence Bar-David et al.

Consequences of voluntary dehydration on cognition have not been thoroughly investigated. In children, Bar-David et al.

: Hydration for improved cognitive function| Benefits of Water for Brain Health | Bethancourt said that because exercise and elevated ambient and body temperatures can have their own, independent effects on cognition, she and the other researchers were interested in the effects of day-to-day hydration status in the absence of exercise or heat stress, especially among older adults. For the study, the researchers used data from a nationally representative sample of women and men who were 60 years of age or older. Data were collected by the Nutrition and Health Examination Survey. Participants gave blood samples and were asked about all foods and drinks consumed the previous day. Total water intake was measured as the combined liquid and moisture from all beverages and foods. Participants also completed three tasks designed to measure different aspects of cognition, with the first two measuring verbal recall and verbal fluency, respectively. A final task measured processing speed, sustained attention, and working memory. Participants were given a list of symbols, each matched with a number between one and nine. They were then given a list of numbers one through nine in random order and asked to draw the corresponding symbol for as many numbers as possible within two minutes. However, much of that was explained by other factors. Third, despite its longitudinal design, water and fluid intake and hydration status were only considered at baseline; however, as the questionnaires measure habitual beverage and food intake, and older adults are considered to have reasonably stable dietary habits [ 37 , 38 ], this is not expected to significantly impact the findings. Along these lines, the possible effect of seasonality on water intake and osmolarity was not considered a concern in the present analyses as the validation of the fluid questionnaire measurements included assessments at various points throughout the year baseline vs. Hence, the finding of no difference between 6-month intervals, suggests no significant differences between opposing seasons e. summer; spring vs. Furthermore, SOSM determination may not necessarily detect acute dehydration or rehydration immediately prior to the cognitive testing, and it is unknown whether observed elevated SOSMs were due to inadequate water intake, ADH abnormality, or other factors. While it is possible that the hydration status of some individuals was misclassified because serum osmolarity was estimated as opposed to being directly measured, the equation has been shown to predict directly measured serum osmolarity well in older adult men and women with and without diabetes or renal issues with a good diagnostic accuracy of dehydration and has been considered a gold standard for the identification of impending and current water-loss dehydration in older adults [ 44 , 45 , 89 , 90 , 91 ]. Lastly, a discrepancy was observed between the percentage of individuals that were considered to have met EFSA fluid intake recommendations and those considered to be dehydrated based on calculated osmolarity. This may have been due to the fact that the EFSA fluid intake recommendations are meant for individuals in good health [ 20 ]; whereas the present study population had overweight or obesity, and it has been shown that individuals with higher BMIs have higher water needs related to metabolic rate, body surface area, body weight, and water turnover rates related to higher energy requirements, greater food consumption, and higher metabolic production [ 92 ]. Strengths of the present analyses include the longitudinal, prospective design, the large sample size, the use of an extensive cognitive test battery, the use of validated questionnaires, and the robustness of the current findings due to the adjustment of relevant covariates. Findings suggest that hydration status, specifically poorer hydration status, may be associated with a greater decline in global cognitive function in older adults with metabolic syndrome and overweight or obesity, particularly in men. Further prospective cohort studies and randomized clinical trials are required to confirm these results and to better understand the link between water and fluid intake, hydration status, and changes in cognitive performance to provide guidance for guidelines and public health. The dataset supporting the conclusions of this article is available upon request pending application and approval of the PREDIMED-Plus Steering Committee. There are restrictions on the availability of data for the PREDIMED-Plus trial, due to the signed consent agreements around data sharing, which only allow access to external researchers for studies following the project purposes. Requestors wishing to access the PREDIMED-Plus trial data used in this study can make a request to the PREDIMED-Plus trial Steering Committee chair: jordi. salas urv. The request will then be passed to members of the PREDIMED-Plus Steering Committee for deliberation. Gauthier S, Rosa-Neto P, Morais JA, Webster C. World Alzheimer Report Journey through the diagnosis of dementia. London: Alzheimer´s Disease International; Petersen RC, Lopez O, Armstrong MJ, Getchius TSD, Ganguli M, Gloss D, et al. Practice guideline update summary: mild cognitive impairment report of the guideline development, dissemination, and implementation. Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar. Scarmeas N, Anastasiou CA, Yannakoulia M. Nutrition and prevention of cognitive impairment. Lancet Neurol. Article PubMed Google Scholar. Johnson EC, Adams WM. Water intake, body water regulation and health. Lorenzo I, Serra-Prat M, Carlos YJ. The role of water homeostasis in muscle function and frailty: a review. Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar. Jéquier E, Constant F. Water as an essential nutrient: the physiological basis of hydration. Eur J Clin Nutr. Kleiner SM. J Am Diet Assoc. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar. Armstrong L, Johnson E. Water intake, water balance, and the elusive daily water requirement. Nissensohn M, Sánchez-Villegas A, Ortega RM, Aranceta-Bartrina J, Gil Á, González-Gross M, et al. Beverage consumption habits and association with total water and energy intakes in the Spanish population: findings of the ANIBES study. Ferreira-Pêgo C, Nissensohn M, Kavouras SA, Babio N, Serra-Majem L, Águila AM, et al. Relative validity and repeatability in a Spanish population with metabolic syndrome from the PREDIMED-PLUS study. Article Google Scholar. Nissensohn M, Sánchez-Villegas A, Galan P, Turrini A, Arnault N, Mistura L, et al. Beverage consumption habits among the European population: association with total water and energy intakes. Rolls BJ, Phillips PA. Aging and disturbances of thirst and fluid balance. Nutr Rev. Kenney WL, Tankersley CG, Newswanger DL, Hyde DE, Puhl SM, Turner NL. Age and hypohydration independently influence the peripheral vascular response to heat stress. J Appl Physiol. Begg DP. Disturbances of thirst and fluid balance associated with aging. Physiol Behav. Hooper L, Bunn D, Jimoh FO, Fairweather-Tait SJ. Water-loss dehydration and aging. Mech Ageing Dev. Lieberman HR. Hydration and cognition: a critical review and recommendations for future research. J Am Coll Nutr. Murray B. Hydration and physical performance. AESAN Scienitific Committee, Alfredo Martínez Hernández J, Cámara Hurtado M, Maria Giner Pons R, González Fandos E, López García E, et al. Informe del Comité Científico de la Agencia Española de Seguridad Alimentaria y Nutrición AESAN de revisión y actualización de las Recomen-daciones Dietéticas Para la población española. Revista del Comité Científico de la AESAN. Google Scholar. Department of Agriculture, U. Department of Health and Human Services. Dietary guidelines for Americans, EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products Nutrition and Allergies NDA. Scientific opinion on dietary reference values for water. EFSA J. Institute of Medicine. Dietary reference intakes for water, potassium, sodium, chloride, and sulfate. Washington, D. Gandy J. Water intake: validity of population assessment and recommendations. Eur J Nutr. Risk reduction of cognitive decline and dementia: WHO guidelines. Geneva: World Health Organization; Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3. Volkert D, Chourdakis M, Faxen-Irving G, Frühwald T, Landi F, Suominen MH, et al. ESPEN guidelines on nutrition in dementia. Clin Nutr. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence NICE. Dementia, disability and frailty in later life-mid-life approaches to delay or prevent onset. NICE guideline; Armstrong-Esther CA, Browne KD, Armstrong-Esther DC, Sander L. The institutionalized elderly: dry to the bone! Int J Nurs Stud. Marra MV, Simmons SF, Shotwell MS, Hudson A, Hollingsworth EK, Long E, et al. Elevated serum osmolality and total water deficit indicate impaired hydration status in residents of long-term care facilities regardless of low or high body mass index. J Acad Nutr Diet. Hooper L, Bunn DK, Downing A, Jimoh FO, Groves J, Free C, et al. Which frail older people are dehydrated? The UK DRIE study. J Gerontol Ser A Biol Sci Med Sci. Neurocognitive disorders and dehydration in older patients: clinical experience supports the hydromolecular hypothesis of dementia. Majdi M, Hosseini F, Naghshi S, Djafarian K, Shab-Bidar S. Total and drinking water intake and risk of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Int J Clin Pract. Bialecka-Dębek A, Pietruszka B. The association between hydration status and cognitive function among free-living elderly volunteers. Aging Clin Exp Res. Suhr JA, Patterson SM, Austin AW, Heffner KL. The relation of hydration status to declarative memory and working memory in older adults. J Nutr Health Aging. Suhr JA, Hall J, Patterson SM, Niinistö RT. The relation of hydration status to cognitive performance in healthy older adults. Int J Psychophysiol. Bethancourt HJ, Kenney WL, Almeida DM, Rosinger AY. Cognitive performance in relation to hydration status and water intake among older adults, NHANES — Martínez-González MA, Buil-Cosiales P, Corella D, Bulló M, Fitó M, Vioque J, et al. Cohort profile: design and methods of the PREDIMED-plus randomized trial. Int J Epidemiol. Salas-Salvadó J, Díaz-López A, Ruiz-Canela M, Basora J, Fitó M, Corella D, et al. Effect of a lifestyle intervention program with energy-restricted Mediterranean diet and exercise on weight loss and cardiovascular risk factors: one-year results of the PREDIMED-plus trial. Diabetes Care. Willett W. Nutritional epidemiology, 3rd edn. Chapter New York: Oxford University Press; Fernández-Ballart JD, Piñol JL, Zazpe I, Corella D, Carrasco P, Toledo E, et al. Relative validity of a semi-quantitative food-frequency questionnaire in an elderly Mediterranean population of Spain. Br J Nutr. Palma I, Farra A, Cantós D. Tablas de composición de alimentos por medidas caseras de consumo habitual en España. Madrid: S. Book Google Scholar. RedBEDCA, AESAN. Base de Datos Española de Composición de Alimentos; Grupo Colaborativo de la Sociedad Española de Nutrición Comunitaria SENC , Aranceta Bartrina J, Arija Val V, Maíz Aldalur E, Martínez de la Victoria Muñoz E, Ortega Anta RM, et al. Dietary guidelines for the Spanish population SENC, December ; the new graphic icon of healthy nutrition. Nutr Hosp. Moreiras O, Carbajal A, Cabrera L, Cuadrado C. Tablas de composición de alimentos Guía de prácticas [Food Composition Tables. Practice Guide]. Madrid: Piramide; Mataix Verdú J, García Diz L, Mañas Almendros M, Martinez de Vitoria E, Llopis González J. Tablas de composición de alimentos [Food composition tables]. Granada; Universidad de Granada; Hooper L, Abdelhamid A, Attreed NJ, Campbell WW, Channell AM, Chassagne P, et al. Clinical symptoms, signs and tests for identification of impending and current water-loss dehydration in older people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. Khajuria A, Krahn J. Osmolality revisited - deriving and validating the best formula for calculated osmolality. Clin Biochem. Hooper L, Bunn DK, Abdelhamid A, Gillings R, Jennings A, Maas K, et al. Water-loss intracellular dehydration assessed using urinary tests: how well do they work? Diagnostic accuracy in older people. Am J Clin Nutr. Blesa R, Pujol M, Aguilar M, Santacruz P, Bertran-Serra I, Hernández G, et al. Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. Benton AL, Hamsher K, Sivan AB. Multilingual aphasia examination. Iowa: AJA Associates; Wechsler D. Wechsler adult intelligence scale-III. San Antonio: Psychological Corporation; Rossi L, Neer C-R, Lopetegui S. Escala de inteligencia Para adultos de WECHSLER. WAIS-III Índice de comprensión verbal. Normas Para los subtests: Vocabulario, analogías e información, Para la ciudad de La Plata Edades: 16 a 24 AñosRevista de Psicología; Aprahamian I, Martinelli JE, Neri AL, Yassuda MS. O Teste do Desenho do Relógio: Revisão da acurácia no rastreamento de demência. Dementia e Neuropsychologia. Paganini-Hill A, Clark LJ. Longitudinal assessment of cognitive function by clock drawing in older adults. Dement Geriatr Cogn Dis Extra. Del Ser QT, García De Yébenes MJ, Sánchez Sánchez F, Frades Payo B, Rodríguez Laso Á, Bartolomé Martínez MP, et al. Evaluación cognitiva del anciano. Datos normativos de una muestra poblacional española de más de 70 años. Med Clin Barc. Llinàs-Reglà J, Vilalta-Franch J, López-Pousa S, Calvó-Perxas L, Torrents Rodas D, Garre-Olmo J. The trail making test: association with other neuropsychological measures and normative values for adults aged 55 years and older from a Spanish-speaking population-based sample. Cognitive performance: a cross-sectional study on serum vitamin D and its interplay with glucose homeostasis in Dutch older adults. J Am Med Dir Assoc. Paz-Graniel I, Babio N, Becerra-Tomás N, Toledo E, Camacho-Barcia L, Corella D, et al. Association between coffee consumption and total dietary caffeine intake with cognitive functioning: cross-sectional assessment in an elderly Mediterranean population. Molina L, Sarmiento M, Peñafiel J, Donaire D, Garcia-Aymerich J, Gomez M, et al. Validation of the REGICOR short physical activity questionnaire for the adult population. PLoS One. Paz-Graniel I, Babio N, Serra-Majem L, Vioque J, Zomeño MD, Corella D, et al. Fluid and total water intake in a senior Mediterranean population at high cardiovascular risk: demographic and lifestyle determinants in the PREDIMED-plus study. Drewnowski A, Rehm CD, Constant F. Water and beverage consumption among adults in the United States: cross-sectional study using data from NHANES — BMC Public Health. Polhuis KCMM, Wijnen AHC, Sierksma A, Calame W, Tieland M. The diuretic action of weak and strong alcoholic beverages in elderly men: a randomized diet-controlled crossover trial. Xu W, Wang H, Wan Y, Tan C, Li J, Tan L, et al. Alcohol consumption and dementia risk: a dose—response meta-analysis of prospective studies. Eur J Epidemiol. Zhang Y, Coca A, Casa DJ, Antonio J, Green JM, Bishop PA. Caffeine and diuresis during rest and exercise: a meta-analysis. J Sci Med Sport. van den Berg B, de Jong M, Woldorff MG, Lorist MM. Caffeine boosts preparatory attention for reward-related stimulus information. J Cogn Neurosci. Chen JQA, Scheltens P, Groot C, Ossenkoppele R. Associations between caffeine consumption, cognitive decline, and dementia: a systematic review. J Alzheimers Dis. Xu W, Tan CC, Zou JJ, Cao XP, Tan L. Sleep problems and risk of all-cause cognitive decline or dementia: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. Rosinger AY, Lawman HG, Akinbami LJ, Ogden CL. The role of obesity in the relation between total water intake and urine osmolality in US adults, You Y, Liu Z, Chen Y, Xu Y, Qin J, Guo S, et al. The prevalence of mild cognitive impairment in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Substituting hydrating foods is also a creative idea in an effort to offer alternatives to drinks. High-water content foods such as broth and cottage cheese, as well as fruits like apples, oranges, berries, and grapes can help avoid dehydration. Make it timely Encourage patients to drink water more often throughout the day rather than right before bed. Make it safe Some medications both prescription and over-the-counter can contribute to dehydration. It is therefore important to review medication side effects and work with the pharmacist and doctor to avoid complications. Source: MIND OVER MATTER v7. Staying Hydrated Boosts Brain Power. Caregiver Information Everyday Information. Nov 23 Written By WBHI Admin. |

| Background | Skip to main content. In young women, cognitive deficits can be readily reversed by replenishing fluids [ 5 ], while in the elderly, the prolonged cellular stress of dehydration may promote brain pathology and continued cognitive decline. Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Del Ser QT, García De Yébenes MJ, Sánchez Sánchez F, Frades Payo B, Rodríguez Laso Á, Bartolomé Martínez MP, et al. There is a lot of information on dehydration among hospitalised and institutionalised elderly, but we only have a small amount of information on the situation in seemingly healthy elderly. Dietary guidelines for Americans, |

| Hydration Is Key: Water Your Brain! | NeuroGrow Brain Fitness Center | To keep your brain adequately hydrated, it is recommended that women consume 2 to 2. It can help to develop a schedule to keep track of daily fluid intake. It is important to keep in mind that cognitive function can also be impaired by overhydration [ 4 ]. Overhydration can lead to drop in sodium levels that can induce delirium and other neurological complications, so fluid consumption should not vastly exceed medically recommended guidelines. Diet and exercise are also important components to remaining hydrated. The hydration guidelines refer to the consumption of all fluids, not simply how many glasses of plain water we drink per day. However, it is counterproductive to start drinking more beverages laden with sugar or artificial sweeteners , since they have their own health risks. Our bodies obtain water from multiple nutritional sources, including many healthy mineral rich foods, so it is possible to get adequate levels of hydration by incorporating more water rich foods into your diet. Some nutritious water rich foods include melon, oranges, berries, lettuce, cucumbers, and tomatoes [ 10 ]. Betsy Mills, PhD, is a member of the ADDF's Aging and Alzheimer's Prevention program. Mills came to the ADDF from the University of Michigan, where she served as the grant writing manager for a clinical laboratory specializing in neuroautoimmune diseases. She also completed a Postdoctoral fellowship at the University of Michigan, where she worked to uncover genes that could promote retina regeneration. She earned her doctorate in neuroscience at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, where she studied the role of glial cells in the optic nerve, and their contribution to neurodegeneration in glaucoma. She obtained her bachelor's degree in biology from the College of the Holy Cross. Mills has a strong passion for community outreach, and has served as program presenter with the Michigan Great Lakes Chapter of the Alzheimer's Association to promote dementia awareness. Raise a Cup for National Coffee Day. Getting Smart About Orange Juice. Is Diet Soda Harming Your Brain Health. Avoid Risks Can dehydration impair cognitive function? January 10, Betsy Mills, PhD. WHAT YOU CAN DO To keep your brain adequately hydrated, it is recommended that women consume 2 to 2. Wittbrodt MT, Sawka MN, Mizelle JC et al. Physiol Rep 6, ee Pross N Effects of Dehydration on Brain Functioning: A Life-Span Perspective. Annals of Nutrition and Metabolism 70 suppl 1 , Wittbrodt MT, Millard-Stafford M Dehydration Impairs Cognitive Performance: A Meta-analysis. Bethancourt HJ, Kenney WL, Almeida DM et al. European Journal of Nutrition. Stachenfeld NS, Leone CA, Mitchell ES et al. Lauriola M, Mangiacotti A, D'Onofrio G et al. Nutrients 10, Sfera A, Cummings M, Osorio C Dehydration and Cognition in Geriatrics: A Hydromolecular Hypothesis. Front Mol Biosci 3, Strengths of the present analyses include the longitudinal, prospective design, the large sample size, the use of an extensive cognitive test battery, the use of validated questionnaires, and the robustness of the current findings due to the adjustment of relevant covariates. Findings suggest that hydration status, specifically poorer hydration status, may be associated with a greater decline in global cognitive function in older adults with metabolic syndrome and overweight or obesity, particularly in men. Further prospective cohort studies and randomized clinical trials are required to confirm these results and to better understand the link between water and fluid intake, hydration status, and changes in cognitive performance to provide guidance for guidelines and public health. The dataset supporting the conclusions of this article is available upon request pending application and approval of the PREDIMED-Plus Steering Committee. There are restrictions on the availability of data for the PREDIMED-Plus trial, due to the signed consent agreements around data sharing, which only allow access to external researchers for studies following the project purposes. Requestors wishing to access the PREDIMED-Plus trial data used in this study can make a request to the PREDIMED-Plus trial Steering Committee chair: jordi. salas urv. The request will then be passed to members of the PREDIMED-Plus Steering Committee for deliberation. Gauthier S, Rosa-Neto P, Morais JA, Webster C. World Alzheimer Report Journey through the diagnosis of dementia. London: Alzheimer´s Disease International; Petersen RC, Lopez O, Armstrong MJ, Getchius TSD, Ganguli M, Gloss D, et al. Practice guideline update summary: mild cognitive impairment report of the guideline development, dissemination, and implementation. Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar. Scarmeas N, Anastasiou CA, Yannakoulia M. Nutrition and prevention of cognitive impairment. Lancet Neurol. Article PubMed Google Scholar. Johnson EC, Adams WM. Water intake, body water regulation and health. Lorenzo I, Serra-Prat M, Carlos YJ. The role of water homeostasis in muscle function and frailty: a review. Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar. Jéquier E, Constant F. Water as an essential nutrient: the physiological basis of hydration. Eur J Clin Nutr. Kleiner SM. J Am Diet Assoc. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar. Armstrong L, Johnson E. Water intake, water balance, and the elusive daily water requirement. Nissensohn M, Sánchez-Villegas A, Ortega RM, Aranceta-Bartrina J, Gil Á, González-Gross M, et al. Beverage consumption habits and association with total water and energy intakes in the Spanish population: findings of the ANIBES study. Ferreira-Pêgo C, Nissensohn M, Kavouras SA, Babio N, Serra-Majem L, Águila AM, et al. Relative validity and repeatability in a Spanish population with metabolic syndrome from the PREDIMED-PLUS study. Article Google Scholar. Nissensohn M, Sánchez-Villegas A, Galan P, Turrini A, Arnault N, Mistura L, et al. Beverage consumption habits among the European population: association with total water and energy intakes. Rolls BJ, Phillips PA. Aging and disturbances of thirst and fluid balance. Nutr Rev. Kenney WL, Tankersley CG, Newswanger DL, Hyde DE, Puhl SM, Turner NL. Age and hypohydration independently influence the peripheral vascular response to heat stress. J Appl Physiol. Begg DP. Disturbances of thirst and fluid balance associated with aging. Physiol Behav. Hooper L, Bunn D, Jimoh FO, Fairweather-Tait SJ. Water-loss dehydration and aging. Mech Ageing Dev. Lieberman HR. Hydration and cognition: a critical review and recommendations for future research. J Am Coll Nutr. Murray B. Hydration and physical performance. AESAN Scienitific Committee, Alfredo Martínez Hernández J, Cámara Hurtado M, Maria Giner Pons R, González Fandos E, López García E, et al. Informe del Comité Científico de la Agencia Española de Seguridad Alimentaria y Nutrición AESAN de revisión y actualización de las Recomen-daciones Dietéticas Para la población española. Revista del Comité Científico de la AESAN. Google Scholar. Department of Agriculture, U. Department of Health and Human Services. Dietary guidelines for Americans, EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products Nutrition and Allergies NDA. Scientific opinion on dietary reference values for water. EFSA J. Institute of Medicine. Dietary reference intakes for water, potassium, sodium, chloride, and sulfate. Washington, D. Gandy J. Water intake: validity of population assessment and recommendations. Eur J Nutr. Risk reduction of cognitive decline and dementia: WHO guidelines. Geneva: World Health Organization; Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3. Volkert D, Chourdakis M, Faxen-Irving G, Frühwald T, Landi F, Suominen MH, et al. ESPEN guidelines on nutrition in dementia. Clin Nutr. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence NICE. Dementia, disability and frailty in later life-mid-life approaches to delay or prevent onset. NICE guideline; Armstrong-Esther CA, Browne KD, Armstrong-Esther DC, Sander L. The institutionalized elderly: dry to the bone! Int J Nurs Stud. Marra MV, Simmons SF, Shotwell MS, Hudson A, Hollingsworth EK, Long E, et al. Elevated serum osmolality and total water deficit indicate impaired hydration status in residents of long-term care facilities regardless of low or high body mass index. J Acad Nutr Diet. Hooper L, Bunn DK, Downing A, Jimoh FO, Groves J, Free C, et al. Which frail older people are dehydrated? The UK DRIE study. J Gerontol Ser A Biol Sci Med Sci. Neurocognitive disorders and dehydration in older patients: clinical experience supports the hydromolecular hypothesis of dementia. Majdi M, Hosseini F, Naghshi S, Djafarian K, Shab-Bidar S. Total and drinking water intake and risk of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Int J Clin Pract. Bialecka-Dębek A, Pietruszka B. The association between hydration status and cognitive function among free-living elderly volunteers. Aging Clin Exp Res. Suhr JA, Patterson SM, Austin AW, Heffner KL. The relation of hydration status to declarative memory and working memory in older adults. J Nutr Health Aging. Suhr JA, Hall J, Patterson SM, Niinistö RT. The relation of hydration status to cognitive performance in healthy older adults. Int J Psychophysiol. Bethancourt HJ, Kenney WL, Almeida DM, Rosinger AY. Cognitive performance in relation to hydration status and water intake among older adults, NHANES — Martínez-González MA, Buil-Cosiales P, Corella D, Bulló M, Fitó M, Vioque J, et al. Cohort profile: design and methods of the PREDIMED-plus randomized trial. Int J Epidemiol. Salas-Salvadó J, Díaz-López A, Ruiz-Canela M, Basora J, Fitó M, Corella D, et al. Effect of a lifestyle intervention program with energy-restricted Mediterranean diet and exercise on weight loss and cardiovascular risk factors: one-year results of the PREDIMED-plus trial. Diabetes Care. Willett W. Nutritional epidemiology, 3rd edn. Chapter New York: Oxford University Press; Fernández-Ballart JD, Piñol JL, Zazpe I, Corella D, Carrasco P, Toledo E, et al. Relative validity of a semi-quantitative food-frequency questionnaire in an elderly Mediterranean population of Spain. Br J Nutr. Palma I, Farra A, Cantós D. Tablas de composición de alimentos por medidas caseras de consumo habitual en España. Madrid: S. Book Google Scholar. RedBEDCA, AESAN. Base de Datos Española de Composición de Alimentos; Grupo Colaborativo de la Sociedad Española de Nutrición Comunitaria SENC , Aranceta Bartrina J, Arija Val V, Maíz Aldalur E, Martínez de la Victoria Muñoz E, Ortega Anta RM, et al. Dietary guidelines for the Spanish population SENC, December ; the new graphic icon of healthy nutrition. Nutr Hosp. Moreiras O, Carbajal A, Cabrera L, Cuadrado C. Tablas de composición de alimentos Guía de prácticas [Food Composition Tables. Practice Guide]. Madrid: Piramide; Mataix Verdú J, García Diz L, Mañas Almendros M, Martinez de Vitoria E, Llopis González J. Tablas de composición de alimentos [Food composition tables]. Granada; Universidad de Granada; Hooper L, Abdelhamid A, Attreed NJ, Campbell WW, Channell AM, Chassagne P, et al. Clinical symptoms, signs and tests for identification of impending and current water-loss dehydration in older people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. Khajuria A, Krahn J. Osmolality revisited - deriving and validating the best formula for calculated osmolality. Clin Biochem. Hooper L, Bunn DK, Abdelhamid A, Gillings R, Jennings A, Maas K, et al. Water-loss intracellular dehydration assessed using urinary tests: how well do they work? Diagnostic accuracy in older people. Am J Clin Nutr. Blesa R, Pujol M, Aguilar M, Santacruz P, Bertran-Serra I, Hernández G, et al. Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. Benton AL, Hamsher K, Sivan AB. Multilingual aphasia examination. Iowa: AJA Associates; Wechsler D. Wechsler adult intelligence scale-III. San Antonio: Psychological Corporation; Rossi L, Neer C-R, Lopetegui S. Escala de inteligencia Para adultos de WECHSLER. WAIS-III Índice de comprensión verbal. Normas Para los subtests: Vocabulario, analogías e información, Para la ciudad de La Plata Edades: 16 a 24 AñosRevista de Psicología; Aprahamian I, Martinelli JE, Neri AL, Yassuda MS. O Teste do Desenho do Relógio: Revisão da acurácia no rastreamento de demência. Dementia e Neuropsychologia. Paganini-Hill A, Clark LJ. Longitudinal assessment of cognitive function by clock drawing in older adults. Dement Geriatr Cogn Dis Extra. Del Ser QT, García De Yébenes MJ, Sánchez Sánchez F, Frades Payo B, Rodríguez Laso Á, Bartolomé Martínez MP, et al. Evaluación cognitiva del anciano. Datos normativos de una muestra poblacional española de más de 70 años. Med Clin Barc. Llinàs-Reglà J, Vilalta-Franch J, López-Pousa S, Calvó-Perxas L, Torrents Rodas D, Garre-Olmo J. The trail making test: association with other neuropsychological measures and normative values for adults aged 55 years and older from a Spanish-speaking population-based sample. Cognitive performance: a cross-sectional study on serum vitamin D and its interplay with glucose homeostasis in Dutch older adults. J Am Med Dir Assoc. Paz-Graniel I, Babio N, Becerra-Tomás N, Toledo E, Camacho-Barcia L, Corella D, et al. Association between coffee consumption and total dietary caffeine intake with cognitive functioning: cross-sectional assessment in an elderly Mediterranean population. Molina L, Sarmiento M, Peñafiel J, Donaire D, Garcia-Aymerich J, Gomez M, et al. Validation of the REGICOR short physical activity questionnaire for the adult population. PLoS One. Paz-Graniel I, Babio N, Serra-Majem L, Vioque J, Zomeño MD, Corella D, et al. Fluid and total water intake in a senior Mediterranean population at high cardiovascular risk: demographic and lifestyle determinants in the PREDIMED-plus study. Drewnowski A, Rehm CD, Constant F. Water and beverage consumption among adults in the United States: cross-sectional study using data from NHANES — BMC Public Health. Polhuis KCMM, Wijnen AHC, Sierksma A, Calame W, Tieland M. The diuretic action of weak and strong alcoholic beverages in elderly men: a randomized diet-controlled crossover trial. Xu W, Wang H, Wan Y, Tan C, Li J, Tan L, et al. Alcohol consumption and dementia risk: a dose—response meta-analysis of prospective studies. Eur J Epidemiol. Zhang Y, Coca A, Casa DJ, Antonio J, Green JM, Bishop PA. Caffeine and diuresis during rest and exercise: a meta-analysis. J Sci Med Sport. van den Berg B, de Jong M, Woldorff MG, Lorist MM. Caffeine boosts preparatory attention for reward-related stimulus information. J Cogn Neurosci. Chen JQA, Scheltens P, Groot C, Ossenkoppele R. Associations between caffeine consumption, cognitive decline, and dementia: a systematic review. J Alzheimers Dis. Xu W, Tan CC, Zou JJ, Cao XP, Tan L. Sleep problems and risk of all-cause cognitive decline or dementia: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. Rosinger AY, Lawman HG, Akinbami LJ, Ogden CL. The role of obesity in the relation between total water intake and urine osmolality in US adults, You Y, Liu Z, Chen Y, Xu Y, Qin J, Guo S, et al. The prevalence of mild cognitive impairment in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Diabetol. Iadecola C, Gottesman RF. Neurovascular and cognitive dysfunction in hypertension: epidemiology, pathobiology, and treatment. Circ Res. An Y, Zhang X, Wang Y, Wang Y, Liu W, Wang T, et al. Longitudinal and nonlinear relations of dietary and serum cholesterol in midlife with cognitive decline: results from EMCOA study. Mol Neurodegener. John A, Patel U, Rusted J, Richards M, Gaysina D. Affective problems and decline in cognitive state in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol Med. Sanz J, Luis A, Carmelo P, Resumen V. Adaptación española del Inventario Para la Depresión de Beck-II BDI-II : 2. Psychometric properties in the general population. Clínica y Salud. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Estimating glomerular filtration rate. Accessed 1 Jun Dementia Care Central, National Institute on Aging. Accessed 5 Jul Masento NA, Golightly M, Field DT, Butler LT, van Reekum CM. Effects of hydration status on cognitive performance and mood. Wittbrodt MT, Millard-Stafford M. Dehydration impairs cognitive performance: a meta-analysis. Med Sci Sports Exerc. Kanbay M, Yilmaz S, Dincer N, Ortiz A, Sag AA, Covic A, et al. Antidiuretic hormone and serum osmolarity physiology and related outcomes: what is old, what is new, and what is unknown? J Clin Endocrinol Metab. Insel TR. Translating oxytocin neuroscience to the clinic: a National Institute of Mental Health perspective. Biol Psychiatry. Lu Q, Lai J, Du Y, Huang T, Prukpitikul P, Xu Y, et al. Sexual dimorphism of oxytocin and vasopressin in social cognition and behavior. Psychol Res Behav Manag. Bluthe R, Gheusi G, Dantzer R. Gonadal steroids influence the involvement of arginine vasopressin in social recognition in mice. Kempton MJ, Ettinger U, Schmechtlg A, Winter EM, Smith L, McMorris T, et al. Effects of acute dehydration on brain morphology in healthy humans. Hum Brain Mapp. Duning T, Kloska S, Steinstrater O, Kugel H, Heindel W, Knecht S. Dehydration confounds the assessment of brain atrophy. Trangmar S, Chiesa S, Kalsi K, Secher N, González-Alonso J. Hydration and the human brain circulation and metabolism. Rasmussen P, Nybo L, Volianitis S, Møller K, Secher NH, Gjedde A. Cerebral oxygenation is reduced during hyperthermic exercise in humans. Acta Physiol. Article CAS Google Scholar. Piil JF, Lundbye-Jensen J, Trangmar SJ, Nybo L. Performance in complex motor tasks deteriorates in hyperthermic humans. Ogoh S. Relationship between cognitive function and regulation of cerebral blood flow. J Physiol Sci. Ogoh S, Tsukamoto H, Hirasawa A, Hasegawa H, Hirose N, Hashimoto T. The effect of changes in cerebral blood flow on cognitive function during exercise. Physiol Rep. Claassen JAHR, Thijssen DHJ, Panerai RB, Faraci FM. Regulation of cerebral blood flow in humans: physiology and clinical implications of autoregulation. Physiol Rev. Hooper L, Abdelhamid A, Ali A, Bunn DK, Jennings A, John WG, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of calculated serum osmolarity to predict dehydration in older people: adding value to pathology laboratory reports. BMJ Open. Lacey J, Corbett J, Forni L, Hooper L, Hughes F, Minto G, et al. A multidisciplinary consensus on dehydration: definitions, diagnostic methods and clinical implications. Ann Med. Siervo M, Bunn D, Prado CM, Hooper L. Accuracy of prediction equations for serum osmolarity in frail older people with and without diabetes. Chang T, Ravi N, Plegue MA, Sonneville KR, Davis MM. Inadequate hydration, BMI, and obesity among US adults: NHANES Ann Fam Med. Download references. We thank all PREDIMED-Plus participants and investigators. CIBEROBN, CIBERESP, and CIBERDEM are initiatives of the Instituto de Salud Carlos III ISCIII , Madrid, Spain. The Hojiblanca Lucena, Spain and Patrimonio Comunal Olivarero Madrid, Spain food companies donated extra virgin olive oil. The Almond Board of California Modesto, CA , American Pistachio Growers Fresno, CA , and Paramount Farms Wonderful Company, LLC, Los Angeles, CA donated nuts for the PREDIMED-Plus pilot study. is supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research CIHR, MFE CG-M is supported by a predoctoral grant from the University of Rovira I Virgili PMF-PIPF CB is supported by a Juan de la Cierva postdoctoral grant from Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades. JS-S, the senior author of this paper, was partially supported by ICREA under the ICREA Academia program. for being the conference attendee voted recipient of the Early Career Researcher Award. None of the funding sources took part in the design, collection, analysis, interpretation of the data; writing of the report; or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. Universitat Rovira i Virgili, Departament de Bioquímica i Biotecnologia, Unitat de Nutrició, Reus, Spain. Stephanie K. Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red Fisiopatología de la Obesidad y la Nutrición CIBEROBN , Institute of Health Carlos III, Madrid, Spain. Nishi, Nancy Babio, Indira Paz-Graniel, Lluís Serra-Majem, Montserrat Fitó, Dolores Corella, Xavier Pintó, Josep A. Tur, J. Toronto 3D Diet, Digestive Tract and Disease Knowledge Synthesis and Clinical Trials Unit, Toronto, ON, Canada. Clinical Nutrition and Risk Factor Modification Centre, St. CIBER de Epidemiología y Salud Pública CIBERESP , Instituto de Salud Carlos III ISCIII , , Madrid, Spain. Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria y Biomédica de Alicante. Universidad Miguel Hernández ISABIAL-UMH , Alicante, Spain. Department of Preventive Medicine, University of Valencia, Valencia, Spain. Lipids and Vascular Risk Unit, Internal Medicine, Hospital Universitario de Bellvitge-IDIBELL, Hospitalet de Llobregat, Barcelona, Spain. School of Medicine, Universitat de Barcelona, , Barcelona, Spain. Department of Preventive Medicine and Public Health, University of Granada, Granada, Spain. Department of Nutrition, Food Sciences, and Physiology, Center for Nutrition Research, University of Navarra, IdiSNA, Pamplona, Spain. Instituto de Investigación Biosanitaria Granada, IBS-Granada, Granada, Spain. Departamento de Ciencias Farmacéuticas y de la Salud, Facultad de Farmacia, Universidad San Pablo-CEU, CEU Universities, Urbanización Montepríncipe, Boadilla del Monte, , Spain. Department of Nutritional Sciences, Faculty of Medicine, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada. Department of Medicine, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada. Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute, St. Department of Preventive Medicine and Public Health, Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria de Navarra IdiSNA , University of Navarra, Pamplona, Spain. You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar. LSM, JV, MF, DC, XP, ABC, JAT, JAM, and JSS contributed to the study concept and design and data extraction from the participants from the PREDIMED-Plus study which provides the framework for the present prospective cohort analysis. SKN, NB, IPG, CGM, and JSS made substantial contributions to the conception of the present study. SKN performed the statistical analyses and initial interpretation of the data. NB, IPG, CGM, and JSS contributed to the review of the statistical analyses and interpretation of the data. SKN drafted the manuscript. All authors substantively reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content and approved the final version to be published. All authors had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Correspondence to Stephanie K. Nishi or Nancy Babio. The PREDIMED-Plus study protocol and procedures were approved by the Research Ethics Committees from each of the participating centers, and the study was registered with the International Standard Randomized Controlled Trial registry ISRCTN; ISRCTN reported receiving grants from Instituto de Salud Carlos III. reported receiving grants from Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Uriach Laboratories, and Grand-Fountain Laboratories for clinical trial and personal fees from Brewers of Europe, Fundación Cerveza y Salud; Instituto Cervantes in Albuquerque, Milano, and Tokyo; Fundación Bosch y Gimpera; non-financial support from Wine and Culinary International Forum, ERAB Belgium , and Sociedad Española de Nutrición; and fees of educational conferences from Pernaud Richart Mexico and Fundación Dieta Mediterránea Spain. reported receiving fees of educational conferences from Fundación para la investigación del Vino y la Nutrición Spain. |

| Hydration may affect cognitive function in some older adults | Lacey J, Corbett J, Forni L, Hooper L, Hughes F, Minto G, et al. Larry Kenney, … Asher Y. January 10, Betsy Mills, PhD. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar Wittbrodt MT, Millard-Stafford M. Furthermore, associations were tested for those participants who had completed the various cognitive tests. Abbreviations : EFSA, European Food Safety Authority; TFWI, total fluid water intake; TWI, total water intake; SOSM, serum osmolarity. |

| Do Concussions Affect Women Differently Than Men? | Adaptación española del Inventario Para improvdd Depresión de Beck-II BDI-II : 2. Improvsd this Hydration for improved cognitive function carried out by Pross Antidepressant for menopause al. Impacts of dehydration on cognitive performance were first studied in extreme conditions, on soldiers or athletes. National Academies Press, Washington, DC. Introduction Cognition I. Basic measurements General information about the respondents was collected with the use of the questionnaire method. |

Hydration for improved cognitive function -

However, fluid and water intake has received limited attention in epidemiological studies, and the literature scarcely examines water intake as a predictor of cognitive performance among older adults. The few studies that have assessed hydration status as a potential predictor of cognitive function among community-dwelling older adults have been inconclusive [ 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 ].

Furthermore, to date, few studies have prospectively captured and examined the impact of water and hydration status on cognitive function over a multi-year period. Therefore, the objective of the present analyses was to prospectively investigate the relation between hydration status, water intake, and 2-year changes in cognitive performance in community-dwelling older adults with metabolic syndrome and overweight or obesity.

This prospective cohort study is based on data collected during the first 2 years of the PREDIMED-Plus PREvención con DIeta MEDiterránea Plus study. Briefly, the PREDIMED-Plus study is an ongoing randomized, parallel-group, 6-year multicenter, controlled trial designed to assess the effect of lifestyle interventions on the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease.

The primary aim of the trial is to assess the effects of an intensive weight loss intervention based on an energy-reduced Mediterranean diet MedDiet , physical activity promotion, and behavioral support intervention group compared to usual care and dietary counseling only with an energy-unrestricted MedDiet control group on the prevention of cardiovascular events.

The PREDIMED-Plus study protocol and procedures were approved by the Research Ethics Committees from each of the participating centers, and the study was registered with the International Standard Randomized Controlled Trial Registry ISRCTN; ISRCTN All participants provided written informed consent.

PREDIMED-Plus participants were recruited from 23 centers across Spain between September and December A total of adults met the eligibility criteria and were randomly allocated in a ratio to either the intervention or the control group.

Couples sharing the same household were randomized together, and the couple was used as a unit of randomization. The present longitudinal analysis involves a sub-study conducted in 10 of the 23 PREDIMED-Plus recruiting centers. For the water and fluid intake analyses, using the interquartile range method using a 1.

Furthermore, associations were tested for those participants who had completed the various cognitive tests. A validated, semi-quantitative item Beverage Intake Assessment Questionnaire BIAQ [ 10 ] and a item validated semi-quantitative FFQ 38 specifying usual portion sizes, were administered by trained dietitians to assess habitual fluid and dietary intakes, respectively.

These two questionnaires have been validated within populations of older, Spanish individuals, which are analogous to the current study population, and both have been found to be reproducible with relative validity [ 10 , 38 ]. The BIAQ recorded the frequency of consumption of various beverage types during the month prior to the visit date.

The average daily fluid intake from beverages was estimated from the servings of each type of beverage. The water and nutrient contents of the beverages were estimated mainly using the CESNID Food Composition Tables [ 39 ], complemented with data from the BEDCA Spanish Database of Food Composition [ 40 ].

The information collected was converted into grams per day, multiplying portion sizes by consumption frequency and dividing the result by the period assessed. Food groups and energy intake were estimated using Spanish food composition tables [ 42 , 43 ].

Drinking water intake, water intake from all fluids, total water intake, EFSA total fluid water intake TFWI , and EFSA total water intake TWI were computed descriptions summarized in Additional file 1 : Table S1.

Drinking water intake was estimated based on tap and bottled water intakes based on BIAQ responses. Water intake from all fluids was computed from tap and bottled water, plus water from other beverages based on responses to the BIAQ.

Total water intake encompassed water intake from all fluids in addition to water present in food sources based on responses to the FFQ. Water intake was further categorized based on established reference values.

The EFSA recommendations for total water intake EFSA TWI for older adults 2. Further categorizations were determined based on total water intake from fluids alone, based on EFSA recommendations EFSA TFWI , where recommended levels for older adults are set to at least 2.

Hydration status was estimated based on calculated serum osmolarity SOSM , which is considered a more reliable biomarker of hydration status than urinary markers in older adults [ 44 ]. Fasting serum glucose, urea, sodium, and potassium were measured by standard methods.

Blood urea nitrogen was determined from urea values using the conversion factor of 0. A battery of 8 neuropsychological tests assessing different cognitive domains was administered at baseline and 2-year follow-up by trained staff to assess cognitive performance.

The following tests were assessed: the Mini-Mental State Examination MMSE , two Verbal Fluency Tests VFTs , two Digit Span Tests DSTs of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-III WAIS-III , the Clock Drawing Test CDT , and two Trail Making Tests TMTs.

Briefly, a Spanish-validated version of the MMSE questionnaire, a commonly used cognitive screening test, was used in the present analysis [ 47 ]. A higher MMSE score indicates better cognitive performance [ 48 ]. The DST of the WAIS-III Spanish version assessed attention and memory.

The DST Forward Recall DST-f is representative of attention and short-term memory capacity, and the DST Backward Recall DST-b is considered as a test of working memory capacity [ 50 , 51 ].

The CDT-validated Spanish version was mainly used to evaluate visuospatial and visuo-constructive capacity [ 52 , 53 , 54 ]. Lastly, the TMT, another tool often used to assess executive function, consists of two parts.

Part A TMT-A assessed attention and processing speed capacities, and part B TMT-B further examined cognitive flexibility [ 55 ]. All instruments included in the cognitive battery have been standardized for the Spanish population in the age range of the study population.

To assess overall cognitive function, a global cognitive function GCF score was determined as the main outcome measure, in addition to evaluating the individual neuropsychological tests supplementary analyses. Raw scores at baseline and scores of changes at 2 years of follow-up for each individual cognitive assessment, as well as GCF, were standardized using the mean and standard deviation from the baseline measurements as normative data, creating z -scores [ 56 ].

GCF was calculated as a composite z -score of all 8 assessments, adding or subtracting each individual test value based on whether a higher score indicates higher or lower cognitive performance, respectively, using the formula:. The trained staff collected baseline socio-demographic i. Leisure time physical activity was estimated using the validated Minnesota-REGICOR Short Physical Activity questionnaire [ 58 ].

These socio-demographic and lifestyle variables were considered as possible covariates because of reports that younger adults, women, individuals with higher educational attainment, married, more active, greater consumers, and non-smokers tend to consume higher amounts of fluids from beverages and foods and hence more likely to meet recommendations on water intake [ 59 , 60 ].

Alcohol was accounted for as a potential covariate as it may act as a diuretic at certain levels [ 61 ] as well as being associated with an elevated risk of dementia when consumed regularly [ 62 ].

Similarly, caffeinated beverages may have a mild diuretic effect [ 63 ], as well as may affect attention and alertness [ 64 ] and could be associated with reduced cognitive decline and dementia risk [ 65 ].

Sleeping habits have also been associated with cognitive health [ 66 ]. Anthropometric measures, including weight and height were measured by trained staff using calibrated scales and wall-mounted stadiometers, respectively.

Body mass index BMI , which may modify the relationship between water intake and hydration status [ 67 ], was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared.

History of chronic disease i. For the present analyses, a prospective cohort study was conducted within the framework of the PREDIMED-Plus study using the database updated to December 22, Participants were categorized into quantiles based on baseline water intake drinking water, water intake from all fluids, total water intake , recommended categories of water intake EFSA TWI, EFSA, TFWI , and hydration status according to serum osmolarity.

Multivariable linear regression models were fitted to assess longitudinal associations comparing the 2-year change in cognitive function across baseline variables of hydration status and water intake and for meeting the EFSA recommendations for TWI and TFWI [ 20 ].

When analyses were performed with categorical variables, p for trend was calculated. The p for linear trend was calculated by assigning the median value of each category and modeling it as a continuous variable.

Multivariable linear regression models were adjusted for several potential confounders. To assess the linear trend, the median value of each category of exposure variables hydration status and various assessments of water and fluid intake was assigned to each participant and was modeled as continuous variables in linear regression models.

The Bonferroni correction was used to correct for multiple comparisons and reduce the risk of a type 1 error. Several stratified and sensitivity analyses were additionally performed to test the robustness of the findings.

First, sex-stratified regression approaches were employed to examine the relationships between hydration status and these water and fluid intake categories and 2-year changes in global cognitive function. A total of participants mean age Table 1 presents the baseline characteristics of the study population according to sex, water tap and bottle intake amount, and hydration status.

No significant associations were observed between the various classifications of water intake i. Hydration status, water and fluid intakes categorically with 2-year changes in global cognitive function z -scores.

b Drinking water refers to tap and bottled water intakes. c Water, all fluids refers to tap and bottled water, plus water from other beverages and fluid food sources, such as soups and smoothies.

d Total water refers to water from all fluids in addition to water present in food sources. e EFSA TFWI refers to the recommended levels of total fluid water intake for older adults at 2. f EFSA TWI refers to the recommended levels of total water intake, from fluids and foods, for older adults at 2.

Abbreviations : EFSA, European Food Safety Authority; TFWI, total fluid water intake; TWI, total water intake; SOSM, serum osmolarity. Hydration status, water and fluid intakes continuously with 2-year changes in global cognitive function z-scores.

Beta represents the changes in global cognitive function, expressed as z -scores, with each hydration or fluid intake component continuously. When each neuropsychological test was investigated separately, participants with the highest category of intake of drinking water 1. Total fluid intake showed similar findings where participants in the highest category of intake of total fluid water 2.

No other associations in the multivariable-adjusted categorical or continuous analyses were observed. When the analyses were stratified by sex, no changes in significance were observed with the associations between water and fluid intakes, in either categorical or continuous investigations, and global cognitive function.

Regarding the sensitivity analyses, associations additionally adjusted for eGFR did not significantly modify the findings Additional file 1 : Tables S5-S7. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first multi-year prospective cohort study to assess the association between water intake from fluid and food sources and hydration status, with subsequent changes in cognitive performance in older Spanish adults with metabolic syndrome and overweight or obesity.

Despite the general acknowledgment that an appropriate level of fluid intake and hydration status is important for health, there have been limited investigations to date assessing the relationship between fluid intake or hydration status and cognitive function.

Existing evidence suggests that good hydration status may be associated with better cognitive test results and that mild, induced dehydration can impair cognitive abilities [ 75 ], but findings are not consistent and there are only a few studies exploring the relationship of hydration status and hardly any assessing amount of water intake, with cognitive performance in older community-dwelling adults.

These cross-sectional findings differ from the present observations where global cognitive function, but not individual tests related to attention and processing, was associated with hydration status. Whereas, correspondingly, water intake but not hydration status was positively associated with DST-f, which is similar to the DSST in that it is an indicator of attention as well as short-term memory capacity, and this was seen across all older adults both men and women.

Additionally, in the NHANES study, cognitive test scores were significantly lower among adults who failed to meet EFSA recommendations on adequate intake AI of water in bivariate analyses, yet this significance was attenuated in the multivariable analyses among both women and men.

Yet, using the alternative AI of daily water intake of mL or more, which is comparable to the highest drinking water intake group in the present study, women scored higher on the Animal Fluency Test, a measure of verbal fluency and hence executive function, and DSST than women with intake levels below this amount, and findings among men trended in the same direction [ 34 ].

Similarly, hydration status has been associated with cognitive function in two cross-sectional studies of older community-dwelling adults by Suhr and colleagues [ 32 , 33 ]. First, Suhr et al. showed that in 28 healthy community-dwelling older adults aged 50 to 82 years , a lower hydration status, determined in this study via total body water measured using the bioelectrical impedance method, was related to a decreased psychomotor processing speed, poorer attention, and memory [ 33 ].

A second cross-sectional study by Suhr et al. Conversely, a cross-sectional study conducted in Poland among 60 community-dwelling older adults aged 60 to 93 years found no significant relationship between cognitive performance, as assessed using the MMSE, TMT, and the Babcock Story Recall Test, and hydration status as assessed by urine specific gravity [ 31 ].

The discrepancy between the findings from this cross-sectional study and the present PREDIMED-Plus analyses might be because all participants in the cross-sectional study from Poland were considered to be adequately hydrated and hence the authors of that study could not assess the impact of a dehydrated state on cognition.

A noteworthy consideration when interpreting the literature and the main findings of the current study for practical use and in the determination of potential mechanisms of action is the distinction between water intake and water balance related to hydration status within the body.

When homeostasis of fluids within the body is disrupted, modifying water intake may impact cognitive function, yet due to the dynamic complexity of body water regulation impacting hydration status may be dependent on individualized physiological water intake needs [ 8 ].

Thus, while the biological mechanism by which water intake and a hydrated status may reduce the risk of cognitive decline is unclear, evidence suggests that aspects related to hydration and fluid homeostasis or a lack thereof, such as hormone regulation and changes in brain structure, could be a key underlying factor.

Several mechanisms regulate water intake and output to maintain serum osmolarity, and hence hydration status, within a narrow range.

Elevated blood osmolarity resulting in the secretion of antidiuretic hormone ADH , also known as vasopressin or arginine vasopressin, a peptide hormone which acts primarily in the kidneys to increase water reabsorption, is one such mechanism that works to return osmolarity to baseline and preserve fluid balance [ 77 ].

In addition to its role in mediating the physiological functions related to water reabsorption and homeostasis, evidence has suggested that ADH participates in cognitive functioning [ 78 ] and that the associated cognitive modulations may further interplay with sex hormones [ 79 ].

Antidiuretic hormone may be influenced by the androgen sex hormone, which is generally more abundant in the brains of males than in females [ 80 ]. As a result, the impact of ADH on cognition could be greater in males [ 80 ]. Exercise- and heat-induced acute dehydration studies implicate possible modifications to the brain structure as another potential mechanism of action for an association between water intake, hydration status, and cognitive function.

Evidence has proposed that acute dehydration can lead to a reduction in brain volume and subtle regional changes in brain morphology such as ventricular expansion, effects that may be reversed following acute rehydration [ 81 , 82 ]. Acute dehydration studies have further implicated hydration status in affecting cerebral hemodynamics and metabolism resulting in declines in cerebral blood flow and oxygen supply [ 83 , 84 ].

A lower vascular and neuronal oxygenation could potentially compromise the cerebral metabolic rate for oxygen, thereby contributing to reductions in cognitive performance [ 81 , 85 , 86 , 87 , 88 ]. Nonetheless, other potential unknown mechanisms cannot be disregarded.

There are several limitations and strengths of the present analyses that need to be acknowledged. The first notable limitation is that the results may not be generalizable to other populations since the participants are older Spanish individuals with metabolic syndrome and overweight or obesity.

However, these questionnaires have been validated and determined as reliable methods of assessing long-term intake in the present study population [ 37 , 38 ].

Third, despite its longitudinal design, water and fluid intake and hydration status were only considered at baseline; however, as the questionnaires measure habitual beverage and food intake, and older adults are considered to have reasonably stable dietary habits [ 37 , 38 ], this is not expected to significantly impact the findings.

Along these lines, the possible effect of seasonality on water intake and osmolarity was not considered a concern in the present analyses as the validation of the fluid questionnaire measurements included assessments at various points throughout the year baseline vs.

Hence, the finding of no difference between 6-month intervals, suggests no significant differences between opposing seasons e.

summer; spring vs. Furthermore, SOSM determination may not necessarily detect acute dehydration or rehydration immediately prior to the cognitive testing, and it is unknown whether observed elevated SOSMs were due to inadequate water intake, ADH abnormality, or other factors.

While it is possible that the hydration status of some individuals was misclassified because serum osmolarity was estimated as opposed to being directly measured, the equation has been shown to predict directly measured serum osmolarity well in older adult men and women with and without diabetes or renal issues with a good diagnostic accuracy of dehydration and has been considered a gold standard for the identification of impending and current water-loss dehydration in older adults [ 44 , 45 , 89 , 90 , 91 ].

Lastly, a discrepancy was observed between the percentage of individuals that were considered to have met EFSA fluid intake recommendations and those considered to be dehydrated based on calculated osmolarity.

This may have been due to the fact that the EFSA fluid intake recommendations are meant for individuals in good health [ 20 ]; whereas the present study population had overweight or obesity, and it has been shown that individuals with higher BMIs have higher water needs related to metabolic rate, body surface area, body weight, and water turnover rates related to higher energy requirements, greater food consumption, and higher metabolic production [ 92 ].

Strengths of the present analyses include the longitudinal, prospective design, the large sample size, the use of an extensive cognitive test battery, the use of validated questionnaires, and the robustness of the current findings due to the adjustment of relevant covariates.

Findings suggest that hydration status, specifically poorer hydration status, may be associated with a greater decline in global cognitive function in older adults with metabolic syndrome and overweight or obesity, particularly in men.

Further prospective cohort studies and randomized clinical trials are required to confirm these results and to better understand the link between water and fluid intake, hydration status, and changes in cognitive performance to provide guidance for guidelines and public health.

The dataset supporting the conclusions of this article is available upon request pending application and approval of the PREDIMED-Plus Steering Committee.

There are restrictions on the availability of data for the PREDIMED-Plus trial, due to the signed consent agreements around data sharing, which only allow access to external researchers for studies following the project purposes. Requestors wishing to access the PREDIMED-Plus trial data used in this study can make a request to the PREDIMED-Plus trial Steering Committee chair: jordi.

salas urv. The request will then be passed to members of the PREDIMED-Plus Steering Committee for deliberation. Gauthier S, Rosa-Neto P, Morais JA, Webster C. World Alzheimer Report Journey through the diagnosis of dementia. London: Alzheimer´s Disease International; Petersen RC, Lopez O, Armstrong MJ, Getchius TSD, Ganguli M, Gloss D, et al.

Practice guideline update summary: mild cognitive impairment report of the guideline development, dissemination, and implementation. Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar. Scarmeas N, Anastasiou CA, Yannakoulia M.

Nutrition and prevention of cognitive impairment. Lancet Neurol. Article PubMed Google Scholar. Johnson EC, Adams WM. Water intake, body water regulation and health. Lorenzo I, Serra-Prat M, Carlos YJ.

The role of water homeostasis in muscle function and frailty: a review. Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar. Jéquier E, Constant F. Water as an essential nutrient: the physiological basis of hydration. Eur J Clin Nutr. Kleiner SM.