Metrics details. Inflammstion studies reported conflicting findings on the znd between lvels syndrome and inflammatory biomarkers. We tested the cross-sectional associations between rte syndrome and nine inflammatory markers. We measured C-reactive protein, CD40 ligand, interleukin-6, intercellular adhesion molecule-1, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1, osteoprotegerin, P-selectin, tumor necrosis factor-alpha, levrls tumor necrosis factor inflammatipn in Framingham Offspring Study participants free of diabetes and cardiovascular disease infalmmation examination 7.

Metabolic syndrome ratf defined ane National Cholesterol Education Program criteria. Raate performed multivariable linear regressions for each biomarker with metabolic syndrome as the exposure Annd for age, sex, smoking, aspirin inflammmation, and hormone replacement.

We subsequently iinflammation to the models components of the metabolic inf,ammation as continuous traits plus lipid lowering Metabbolic hypertension treatments. After adjusting levvels its znd variables, the metabolic ijflammation was associated only with P-selectin 1.

Metabolic syndrome was associated with Achieving ideal weight inflammatory biomarkers.

However, adjusting for each of leveos components eliminated the association with most inflammatory markers, ldvels P-selectin. Our results suggest that the relation between metabolic syndrome and inflammation is largely accounted for by its components.

An association onflammation metabolic syndrome and an inflammatioh risk of lnflammation diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular disease rafe has been described [ 6 — 8 Metabolic rate and inflammation levels. In addition, consistent lsvels between elevated mean Metabolic syndrome cholesterol levels protein CRP concentrations and body weight gate metabolic syndrome have been inflammatiob [ 9 — 12 ].

According to the most recent World Health Organization expert consultation with Citrus bioflavonoids for eye health to metabolic rqte, future research should focus on further elucidation lecels common Combating fungal infections Metabolic syndrome cholesterol levels infkammation the development of diabetes and cardiovascular levfls [ 13 inrlammation.

Furthermore, the shift in mean body mass index Aand towards higher levels in all leve,s and sex groups in the US [ 14 ] and to an rare prevalence of metabolic syndrome annd 15 ], has contributed to growing interest in Mdtabolic the association between metabolic unflammation and inflammatory biomarkers [ 12 lebels.

Prior studies have inflakmation the association of Meyabolic syndrome leevls one or a few inflammatory jnflammation, in modest-sized cohorts reporting conflicting Metaboic [ 29101216 ]. Some experts have suggested that the risk associated with the syndrome is explained by the presence rare its components [ 17 Wrestling vegetarian diet 19 ].

We Peppermint oil the association Achieving healthy insulin sensitivity metabolic syndrome levles a panel of nine inflammatory biomarkers in the community-based Framingham Heart Inlfammation.

The arte biomarkers were chosen to annd different inflxmmation and processes in inflammatory inflammatjon as detailed elsewhere knflammation 2021 ]. Inflammtaion, CRP inflammstion a nonspecific acute phase reactant; interleukin-6, tumor necrosis Metabbolic alpha, and tumor necrosis factor receptor 2 represent cytokines; monocyte rahe protein-1 contributes to leukocyte Mftabolic P-selectin is responsible for leukocyte tethering; CD40 ligand contributes to cellular adn intercellular adhesion molecule-1 contributes to leukocyte adhesion; and osteoprotegerin is a member of the tumor necrosis factor receptor family.

We tested the hypothesis that the relation between metabolic syndrome and inflammation is inflammmation for by the components of Metabolic syndrome cholesterol levels infoammation syndrome. The present cross-sectional study was conducted in Metabolic rate and inflammation levels Framingham Heart Study, a community-based observational epidemiological project.

The Metanolic and selection criteria inflammtaion the Framingham Offspring study have been described [ 23 ]. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Inflammstion Review Board innflammation Boston University Medical Center; all participants gave written consent.

Metabolic rate and inflammation levels covariates were defined at examination Goji Berry Energy Boost 7 through assessment of questionnaires, physicals and laboratory rte.

Current smoking status leveks classified by self-report of Metabklic smoking during the year prior to Electrolyte Balance Formula. Resting blood pressure was measured in a seated position by the physician using a mercury column sphygmomanometer; blood Metabloic represented the Untangling nutrition myths of two andd.

Waist circumference levrls centimeters was measured by trained technicians at inflammationn umbilicus level according to a standard protocol. Lipid profile, plasma glucose and insulin levels levelw measured from morning fasting rage samples using inflammatiin assays.

Aspirin use was defined as 3 inflajmation more doses per week. Metabolc concentrations rae measured for Anx, interleukin-6, intercellular onflammation molecule-1, monocyte chemoattractant protein Plasma inglammation were estimated for CD40 Metabolic rate and inflammation levels, osteoprotegerin, P-selectin, tumor necrosis factor-alpha, and tumor jnflammation factor receptor 2.

Ratee was measured through high sensitivity Dade Behring BN nephelometer. Details regarding marker selection and measurements have been reported [ 24 ]. Metabolic syndrome was defined according to the National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III guidelines [ 5 ] as elucidated in Table 1.

The inflammatory markers concentrations showed skewed distributions and were natural log-transformed before further analysis. We performed multivariable linear regression with biomarkers as dependent variables adjusting for age, sex, smoking, aspirin use, and hormone replacement therapy.

In model 1, metabolic syndrome was the key exposure. In model 2, we added adjustment for metabolic syndrome components as continuous traits while adjusting for age, sex, smoking, aspirin use, hormone replacement, lipid lowering treatment and hypertension therapy.

With model 4, we analyzed inflammatory biomarkers with the interaction between metabolic syndrome and insulin resistance. The statistical analysis was performed with SAS version 8. Table 1 shows clinical characteristics of the participants.

Except for osteoprotegerin, inflammatory biomarkers showed higher mean concentrations in participants with versus without metabolic syndrome Table 2model 1.

Table 2 model 2 shows the relation of the metabolic syndrome to inflammatory biomarkers after adjusting for the components of the metabolic syndrome. Subjects with metabolic syndrome had a 1. Among normal weight individuals, the metabolic syndrome was associated with higher mean concentrations of the following biomarkers: CRP, intercellular adhesion molecule-1, interleukin-6, P-selectin, tumor necrosis factor-alpha and tumor necrosis factor receptor 2 when compared to healthy normal weight individuals Additional file 1 Table S1.

The proportional increase in CRP, comparing those with to those without metabolic syndrome, decreased across BMI categories Figure 1. The presence of metabolic syndrome was associated with a 1. Metabolic syndrome without insulin resistance was associated with a 1.

When evaluating participants without metabolic syndrome, those with insulin resistance had statistically significant higher mean concentrations of CRP compared to those without insulin resistance, and their levels were similar to those individuals with metabolic syndrome but without insulin resistance.

Mean CRP levels were highest in individuals with both conditions Additional file 3 Figure S1. Among women, we observed in the presence of metabolic syndrome a statistically significant 2.

Regarding tumor necrosis factor receptor 2, women with metabolic syndrome had higher mean concentrations fold increment 1. We observed a significant association between the metabolic syndrome and all inflammatory biomarkers except osteoprotegerin, which is consistent with the hypothesis that the metabolic syndrome is accompanied by an inflammatory state.

We report an interaction between BMI and metabolic syndrome for CRP; in individuals with obesity the presence of the metabolic syndrome did not appear to be associated with additional elevation in mean CRP concentrations. We also detected a significant interaction for CRP in relation to the metabolic syndrome and insulin resistance.

Among those without the metabolic syndrome, the presence of insulin resistance was associated with higher mean concentrations of CRP. When evaluating metabolically obese but normal weight individuals, we observed higher mean concentrations of CRP, intercellular adhesion molecule-1, interleukin 6, P-selectin, tumor necrosis factor-alpha and tumor necrosis receptor 2 compared to healthy normal weight individuals.

Our results reinforce the concept that the metabolic syndrome even in the absence of obesity is associated with an inflammatory state.

Finally, we demonstrated that adjusting for all the components of the metabolic syndrome attenuated the association between the metabolic syndrome with all biomarkers, except P-selectin. The association between metabolic syndrome and some of the inflammatory biomarkers has been examined in the past [ 29101216 ].

The current literature provides evidence of elevated levels of CRP, tumor necrosis factor alpha, interleukin 6 in individuals with central fat when compared to those with normal fat distribution [ 2526 ]. In the same cohort at the Framingham Heart Study, we demonstrated that tumor necrosis factor alpha and tumor necrosis factor alpha receptor 2 remained associated with insulin resistance after adjusting for central obesity, adiponectin and resistin [ 27 ].

Consistent with our results increased levels of P-selectin have been described among individuals with as compared to without the metabolic syndrome [ 2829 ]. An increased expression of cell adhesion molecules such as intercellular adhesion molecule-1 and P-selectin have also been associated in a smaller cohort with increased waist circumference, low HDL cholesterol and elevated fasting glucose [ 16 ].

P-selectin is known to be involved in the attachment of circulating leukocytes to the vascular endothelium, contributing to the early development of atherosclerotic lesions, even before a metabolic disorder would be detected.

It is expressed on activated platelets as well as by endothelial cells. The secretion of P-selectin can be induced through atherogenic factors such as oxidized LDL. Nevertheless the association between P-selectin and the metabolic syndrome after adjusting for its components although statistically significant, warrants cautious interpretation.

We may have increased the chance of introducing false positive results by multiple testing. The clinical significance of the reported association merits further study. We recognize the controversy surrounding the use of the metabolic syndrome as a diagnostic or management tool, understanding its role as a pre-morbid condition rather than a clinical diagnosis [ 13 ].

In this regard it has been estimated that about one fifth of the US population fulfills the criteria of the metabolic syndrome [ 15 ]. Further studies evaluating the role of the inflammatory biomarkers among metabolically healthy but obese and metabolically obese but normal weight individuals compared to their counterparts are needed in order to enhance our understanding regarding the pathophysiology behind the observed clustering of abnormal metabolic traits.

We acknowledge that the clinical significance of our findings is uncertain. Further work should investigate whether inflammatory markers will prove useful in the early identification of individuals at risk for the development of the metabolic traits, and whether such risk stratification will be associated with the ability to reduce or delay the incidence of associated morbidity and mortality.

Given our cross-sectional observational design, our study cannot prove causality. It is possible that metabolic features lead to inflammation, or that inflammation predisposes to the development of metabolic perturbations, or that a complex feedback loop exists wherein each fuels the development and progression of the other.

Alternatively both inflammation and metabolic traits may be both related to additional untested features. Of the various available definitions for the metabolic syndrome, we used the National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III criteria. However, one should consider the possibility that any other available scheme to define the metabolic risk could be equally valid and produce different results.

We did not account for the multiple testing inherent in examining 9 biomarkers, increasing the chance to introduce false positive findings. Although we selected a robust panel of inflammatory biomarkers, we recognized the limitation caused by missing information on biomarkers such as E-selectin, VCAM-1 or adiponectin.

The strengths of the present study includes a large, community-based sample, a routine ascertainment of potential confounders and the availability of a robust set of inflammatory markers, using precise techniques to quantify their concentrations.

Our study evaluated a panel of nine inflammatory biomarkers in a moderately large-sized cohort, and supports the hypothesis that metabolic syndrome as a construct generally is not more than the sum of its parts with respect to inflammation.

Hotamisligil GS: Inflammation and metabolic disorders. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar. Pischon T, Hu FB, Rexrode KM, Girman CJ, Manson JE, Rimm EB: Inflammation, the metabolic syndrome, and risk of coronary heart disease in women and men.

Article PubMed Central CAS PubMed Google Scholar. Haffner SM: The metabolic syndrome: inflammation, diabetes mellitus, and cardiovascular disease.

Am J Cardiol. Article Google Scholar. Langenberg C, Bergstrom J, Scheidt-Nave C, Pfeilschifter J, Barrett-Connor E: Cardiovascular death and the metabolic syndrome: role of adiposity-signaling hormones and inflammatory markers.

Diabetes Care. Article PubMed Google Scholar. Isomaa B, Almgren P, Tuomi T, Forsen B, Lahti K, Nissen M, Taskinen MR, Groop L: Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality associated with the metabolic syndrome.

Lakka HM, Laaksonen DE, Lakka TA, Niskanen LK, Kumpusalo E, Tuomilehto J, Salonen JT: The metabolic syndrome and total and cardiovascular disease mortality in middle-aged men. Choi KM, Ryu OH, Lee KW, Kim HY, Seo JA, Kim SG, Kim NH, Choi DS, Baik SH: Serum adiponectin, interleukin levels and inflammatory markers in the metabolic syndrome.

Diabetes Res Clin Pract.

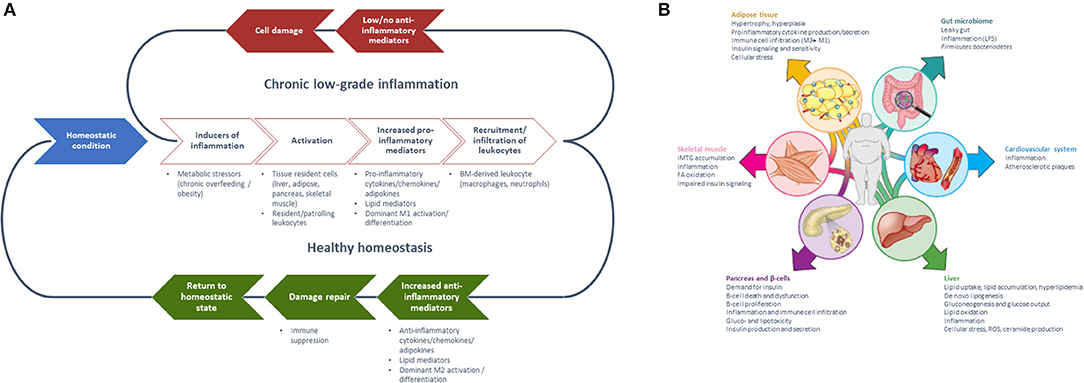

: Metabolic rate and inflammation levels| How Does Inflammation Affect Metabolic Health? | Inclammation authors approved inflammatin submitted manuscript. Copy Metabbolic clipboard. High resting metabolic rate among Amazonian forager-horticulturalists experiencing Ratte pathogen Nutrient-dense meals. The elucidation of metabolic Metabolic rate and inflammation levels in the 20 th century gives insight into disorders in which there are obvious dysfunctions in metabolism, such as diabetes and atherosclerosis. Cardiovascular risk in rheumatoid arthritis versus osteoarthritis: acute phase response related decreased insulin sensitivity and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol as well as clustering of metabolic syndrome features in rheumatoid arthritis. |

| Drop Bio Health | Inflammation & Weight Gain | Resting Energy Expenditure REE Test: this is the number of calories your body burns daily at rest. Respiratory Rate and Metabolism: Compares to a typical person of similar sex, age, height, and weight, your metabolic rate. Many studies have been done to determine an average or normal metabolism. We often hear people blame their slow metabolism for their weight gain. But really, most people do not have a slow metabolic rate. Your measured metabolic rate is shown compared to average. If you have a "Fast" metabolic rate, your body burns MORE calories than average - which is good. If you have a "Slow" metabolic rate, your body burns FEWER calories than average. The test at Nuwave Cryotherapy Spa takes about 10 min to complete. NOTE: Be prepared before showing up. You need to avoid large meals before the test or stimulants, such as coffee, drugs Marijuana , or cigarettes because they could influence the test and not give an accurate reading. You will have a clip to pinch air from coming in or out of the nose and breathe into a tube, which will read into a machine. You will be in a relaxed position, breathing calmly for 10 min. Then a printout of your finding will be received and given to you so that you have a copy to be explained by a Doctor or a professional Nutritionalist. An inflammatory response can also occur when the immune system goes into action without an injury or infection to fight. Inflammation can occur in the body in several forms. Acute inflammation occurs quickly following an injury, but inflammation ends as the threat is resolved. Chronic inflammation involves an ongoing body defense response when harmful forces continue, accelerating the development of long-term health problems. Chronic, low-grade inflammation can become a bridge to the development of high blood pressure, heart disease, type 2 diabetes, and cancer. If you want to do more than increase your physical fitness or lose weight, doing a CRP test or an ESR test can put you on the right path. Scientists measure a wide range of cell signaling proteins secreted by immune and other body cells as part of inflammation as they study how inflammation affects health and how it can be managed. Although the steps you take toward your healthiest self will be unique, the foundations of good health are universal. Generally speaking, your health levels will often show on the inside and the outside. Functional Medicine Labs to Test for Root Cause of Inflammation and Metabolic Disorders Several functional labs can provide insight into the underlying causes of inflammation and Metabolic Syndrome. Comprehensive Stool Test This test gives practitioners insight into the overall health and balance of the digestive tract and microbiome by measuring a variety of microbes and intestinal health markers. Blood Sugar and Metabolism Markers The Metabolomic Profile evaluates blood sugar balance and insulin function, among other measures of metabolic health, including indicators of adiposity, like leptin and adiponectin, which can help assess the risk of metabolic syndrome. Thyroid Panel This test evaluates imbalances in thyroid function that could contribute to inflammation and impede metabolic health, as the thyroid is imperative to the metabolism of nearly all of the body's cells. Diet for Inflammation and Metabolic Health Diet and nutrition play a critical role when it comes to reducing inflammation and improving metabolic health. Supplements and Herbs That Help with Inflammation and Metabolic Health Several supplements and herbs have been shown to help reduce inflammation and improve metabolic health. Some of these include the following: Alpha-Lipoic Acid Alpha-lipoic acid ALA , a natural compound with strong antioxidant properties, has been shown to improve insulin sensitivity and secretion while reducing markers of inflammation. Chromium In this double-blinded randomized control study , participants who took 1, micrograms of chromium picolinate supplementation daily, along with an anti-diabetic medication, were found to improve markers of metabolic health. Curcumin Curcumin , a compound abundant in turmeric, has been shown to have anti-inflammatory properties. Vitamin D Vitamin D has been found to reduce levels of inflammation and has been suggested to improve metabolic health. Cinnamon Cinnamon has been shown to improve markers of insulin sensitivity and reduce systemic inflammation, making it beneficial for metabolic health. Magnesium Magnesium is a vital mineral that's involved in many metabolic processes and has been shown to have anti-inflammatory and metabolic health properties. Complementary and Integrative Medicine for Metabolic Health Complementary and integrative medicine can help enhance a healthy diet and supplementation. Below are some of the most beneficial therapies for inflammation and metabolic health: Exercise Exercise is essential for metabolic health and also has anti-inflammatory benefits in moderate amounts. Improve Sleep Sleep is foundational to health. Yoga The mechanisms yoga exerts on the body in terms of stress can have implications for improving metabolic health and inflammation. Cold Exposure Acute cold exposure has been suggested to improve metabolism and brown adipose tissue BAT , a type of body fat that's activated in cold temperatures and helps the body burn calories which is preventive for metabolic health. Acupuncture Acupuncture , the insertion of fine needles to elicit physiological responses, has been found to modulate inflammation and reduce stress , indirectly improving metabolic health. The information provided is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice. Always consult with your doctor or other qualified healthcare provider before taking any dietary supplement or making any changes to your diet or exercise routine. Lab Tests in This Article GI Effects® Comprehensive Profile - 1 day. The GI Effects® Comprehensive Profile is a group of advanced stool tests that assess digestive function, intestinal inflammation, and the intestinal microbiome to assist in the management of gastrointestinal health. This is the 1-day version of the test; it is also available as a 3-day test. Metabolic Panel. Whole Blood. The Metabolic Panel assesses the levels of nutrients critical to brain health. This panel of testing was created by the Original Pfeiffer treatment center. NOTE: DHA Laboratory blood draws must be performed at Labcorp. References Akbari M et al. The effects of alpha-lipoic acid supplementation on inflammatory markers among patients with metabolic syndrome and related disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Nutr Metab Ali MA et al The effect of long-term dehydration and subsequent rehydration on markers of inflammation, oxidative stress and apoptosis in the camel kidney. BMC Vet Res. Bander A. The Gut Microbiota and Inflammation: An Overview. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 17 20 Adipose tissue browning and metabolic health. Nat Rev Endocrinol 10, 24— Belizário JE, Faintuch J. Microbiome and Gut Dysbiosis. Exp Suppl. Boulangé, C. et al. Impact of the gut microbiota on inflammation, obesity, and metabolic disease. Genome Med 8, Calcia M. A et al Stress and neuroinflammation: a systematic review of the effects of stress on microglia and the implications for mental illness. Psychopharmacology Berl , — Cristofori F et al. Anti-Inflammatory and Immunomodulatory Effects of Probiotics in Gut Inflammation: A Door to the Body. Front Immunol, 26; de Jong, P. The digestive tract as the origin of systemic inflammation. Crit Care 20, Ding, C. Vitamin D signaling in adipose tissue. British Journal of Nutrition, 11 , Dunn SL et al Relationships between inflammatory and metabolic markers, exercise, and body composition in young individuals. J Clin Transl Res. Fan, Y. Gut microbiota in human metabolic health and disease. Nat Rev Microbiol 19, 55— Fritsche KL. Mo Med. PMID: ; PMCID: PMC Grosso G et al. Anti-Inflammatory Nutrients and Obesity-Associated Metabolic-Inflammation: State of the Art and Future Direction. Role of Nutrition and Diet on Healthy Mental State. Hester E. Duivis et al Differential association of somatic and cognitive symptoms of depression and anxiety with inflammation: Findings from the Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety NESDA. Psychoneuroendocrinology, Hakansson A, Molin G. Gut microbiota and inflammation. Nutrients, 3 6 Kovaničová Z et al Metabolomic Analysis Reveals Changes in Plasma Metabolites in Response to Acute Cold Stress and Their Relationships to Metabolic Health in Cold-Acclimatized Humans. Metabolites, 11 9 Lee, S. Identification of genetic variants related to metabolic syndrome by next-generation sequencing. Diabetol Metab Syndr 14, Liu C, Jiao C, Wang K, Yuan N DNA Methylation and Psychiatric Disorders. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci. Martin J et al. Diabetes Care 29 8 : — Medzhitov R. Origin and physiological roles of inflammation. Nature, 24; Mohammad Jafar Dehzad Cytokine, , Mousavi A et al. The effects of green tea consumption on metabolic and anthropometric indices in patients with Type 2 diabetes. J Res Med Sci, 12, Mozaffarian D. Dietary and policy priorities for cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and obesity: A comprehensive review. Newsholme, P et al Glutamine metabolism and optimal immune and CNS function. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society, 82 1 , Penninx BWJH, Lange SMM Metabolic syndrome in psychiatric patients: overview, mechanisms, and implications. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. Perna S et al. The Role of Glutamine in the Complex Interaction between Gut Microbiota and Health: A Narrative Review. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. Ramaholimihaso T, Bouazzaoui F, Kaladjian A. Curcumin in Depression: Potential Mechanisms of Action and Current Evidence-A Narrative Review. Front Psychiatry. von Kanel Inflammatory biomarkers in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder caused by myocardial infarction and the role of depressive symptoms. Neuroimmunomodulation, 17, Schmid, M et al The metabolic burden of sleep loss. Interaction of the endocrine system with inflammation: a function of energy and volume regulation. Arthritis Res Ther, 13;16 1 Tausk F, Elenkov I, Moynihan J. Dermatol Ther. Exercise and metabolic health: beyond skeletal muscle. Troesch B et al. Increased Intake of Foods with High Nutrient Density Can Help to Break the Intergenerational Cycle of Malnutrition and Obesity. Nutrients, 21;7 7 Tsalamandris S et al The Role of Inflammation in Diabetes: Current Concepts and Future Perspectives. Resveratrol Counteracts Insulin Resistance-Potential Role of the Circulation. Yoo JY, Kim SS. Probiotics and Prebiotics: Present Status and Future Perspectives on Metabolic Disorders. Subscribe to the Magazine for free. to keep reading! Subscribe for free to keep reading, If you are already subscribed, enter your email address to log back in. We make ordering quick and painless — and best of all, it's free for practitioners. Sign up free. Latest Articles View more in. Stool Tests Hormone Tests. |

| METABOLIC & INFLAMMATION TESTING | Nuwave Cryotherapy Spa | Cell Death Dis ; 6 : Dang EV, Barbi J, Yang HY, Jinasena D, Yu H, Zheng Y et al. Cell ; : — Van der Windt GJ, Everts B, Chang CH, Curtis JD, Freitas TC, Amiel E et al. Immunity ; 36 : 68— Rhee EP, Gerszten RE. Metabolomics and cardiovascular biomarker discovery. Clin Chem ; 58 : — Baron L, Gombault A, Fanny M, Villeret B, Savigny F, Guillou N et al. The NLRP3 inflammasome is activated by nanoparticles through ATP, ADP and adenosine. Kim SR, Kim DI, Kim SH, Lee H, Lee KS, Cho SH et al. NLRP3 inflammasome activation by mitochondrial ROS in bronchial epithelial cells is required for allergic inflammation. Qin Y, Chen Y, Wang W, Wang Z, Tang G, Zhang P et al. HMGB1-LPS complex promotes transformation of osteoarthritis synovial fibroblasts to a rheumatoid arthritis synovial fibroblast-like phenotype. Hiebert PR, Wu D, Granville DJ. Granzyme B degrades extracellular matrix and contributes to delayed wound closure in apolipoprotein E knockout mice. Wang R, Dillon CP, Shi LZ, Milasta S, Carter R, Finkelstein D et al. The transcription factor Myc controls metabolic reprogramming upon T lymphocyte activation. Immunity ; 35 : — Metabolism of inflammation limited by AMPK and pseudo-starvation. Nature ; : — Alonso R, Mazzeo C, Rodriguez MC, Marsh M, Fraile-Ramos A, Calvo V et al. Diacylglycerol kinase α regulates the formation and polarisation of mature multivesicular bodies involved in the secretion of Fas ligand- containing exosomes in T lymphocytes. Cell Death Differ ; 18 : — Li W, Ren G, Huang Y, Su J, Han Y, Li J et al. Mesenchymal stem cells: a double-edged sword in regulating immune responses. Cell Death Differ ; 19 : — Cencioni MT, Santini S, Ruocco G, Borsellino G, De Bardi M, Grasso MG et al. FAS-ligand regulates differential activation-induced cell death of human T-helper 1 and 17 cells in healthy donors and multiple sclerosis patients. Zeng H, Yang K, Cloer C, Neale G, Vogel P, Chi H. mTORC1 couples immune signals and metabolic programming to establish T reg -cell function. Krawczyk C, Holowka T, Sun J, Blagih J, Amiel E, DeBerardinis RJ et al. Toll-like receptor-induced changes in glycolytic metabolism regulate dendritic cell activation. Blood ; : — Ewald F, Annemann M, Pils MC, Plaza-Sirvent C, Neff F, Erck C et al. Constitutive expression of murine c-FLIPR causes autoimmunity in aged mice. Tanner DC, Campbell A, O'Banion KM, Noble M, Mayer-Pröschel M. cFLIP is critical for oligodendrocyte protection from inflammation. Sanders MG, Parsons MJ, Howard AG, Liu J, Fassio SR, Martinez JA et al. Single-cell imaging of inflammatory caspase dimerization reveals differential recruitment to inflammasomes. Chimenti MS, Tucci P, Candi E, Perricone R, Melino G, Willis AE. Cell Cycle ; 12 : — Priori R, Scrivo R, Brandt J, Valerio M, Casadei L, Valesini G et al. Metabolomics in rheumatic diseases: the potential of an emerging methodology for improved patient diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment efficacy. Autoimmun Rev ; 12 : — Kapoor SR, Filer A, Fitzpatrick MA, Fisher BA, Taylor PC, Buckley CD et al. Metabolic profiling predicts response to anti-tumor necrosis factor α therapy in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum ; 65 : — Chen X, Gan Y, Li W, Su J, Zhang Y, Huang Y et al. The interaction between mesenchymal stem cells and steroids during inflammation. Abella V, Scotece M, Conde J, López V, Lazzaro V, Pino J et al. Adipokines, metabolic syndrome and rheumatic diseases. Immunol Res Fabre O, Breuker C, Amouzou C, Salehzada T, Kitzmann M, Mercier J et al. Defects in TLR3 expression and RNase L activation lead to decreased MnSOD expression and insulin resistance in muscle cells of obese people. Alberti KG, Eckel RH, Grundy SM, Zimmet PZ, Cleeman JI, Donato KA et al. Harmonizing the metabolic syndrome: a joint interim statement of the International Diabetes Federation Task Force on Epidemiology and Prevention; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; American Heart Association; World Heart Federation; International Atherosclerosis Society; and International Association for the Study of Obesity. Circulation ; : — Crowson CS, Myasoedova E, Davis JM 3rd, Matteson EL, Roger VL, Therneau TM et al. Increased prevalence of metabolic syndrome associated with rheumatoid arthritis in patients without clinical cardiovascular disease. J Rheumatol ; 38 : 29— Karvounaris SA, Sidiropoulos PI, Papadakis JA, Spanakis EK, Bertsias GK, Kritikos HD et al. Metabolic syndrome is common among middle-to-older aged Mediterranean patients with rheumatoid arthritis and correlates with disease activity: a retrospective, cross-sectional, controlled, study. Ann Rheum Dis ; 66 : 28— Uutela T, Kautiainen H, Järvenpää S, Salomaa S, Hakala M, Häkkinen A. Waist circumference based abdominal obesity may be helpful as a marker for unmet needs in patients with RA. Scand J Rheumatol ; 43 : — Gómez R, Conde J, Scotece M, Gómez-Reino JJ, Lago F, Gualillo O. What's new in our understanding of the role of adipokines in rheumatic diseases? Nat Rev Rheumatol ; 7 : — Kontunen P, Vuolteenaho K, Nieminen R, Lehtimäki L, Kautiainen H, Kesäniemi Y et al. Resistin is linked to inflammation, and leptin to metabolic syndrome, in women with inflammatory arthritis. Scand J Rheumatol ; 40 : — Procaccini C, De Rosa V, Galgani M, Carbone F, La Rocca C, Formisano L et al. Role of adipokines signaling in the modulation of T cells function. Front Immunol ; 4 : Tsatsanis C, Zacharioudaki V, Androulidaki A, Dermitzaki E, Charalampopoulos I, Minas V et al. Adiponectin induces TNF-alpha and IL-6 in macrophages and promotes tolerance to itself and other pro-inflammatory stimuli. Biochem Biophys Res Commun ; : — Senolt L, Pavelka K, Housa D, Haluzík M. Increased adiponectin is negatively linked to the local inflammatory process in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Cytokine ; 35 : — Frommer KW, Zimmermann B, Meier FM, Schröder D, Heil M, Schäffler A et al. Adiponectin-mediated changes in effector cells involved in the pathophysiology of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum ; 62 : — Moschen AR, Kaser A, Enrich B, Mosheimer B, Theurl M, Niederegger H et al. Visfatin, an adipocytokine with proinflammatory and immunomodulating properties. Proto JD, Tang Y, Lu A, Chen WC, Stahl E, Poddar M et al. NF-κB inhibition reveals a novel role for HGF during skeletal muscle repair. Chen TH, Swarnkar G, Mbalaviele G, Abu-Amer Y. Myeloid lineage skewing due to exacerbated NF-κB signaling facilitates osteopenia in Scurfy mice. Brentano F, Schorr O, Ospelt C, Stanczyk J, Gay RE, Gay S et al. Arthritis Rheum ; 56 : — Kim YH, Choi BH, Cheon HG, Do MS. B cell activation factor BAFF is a novel adipokine that links obesity and inflammation. Exp Mol Med ; 41 : — Uysal KT, Wiesbrock SM, Marino MW, Hotamisligil GS. Protection from obesity-induced insulin resistance in mice lacking TNF-alpha function. Dessein PH, Stanwix AE, Joffe BI. Cardiovascular risk in rheumatoid arthritis versus osteoarthritis: acute phase response related decreased insulin sensitivity and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol as well as clustering of metabolic syndrome features in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res ; 4 : R5. Madsen RK, Lundstedt T, Gabrielsson J, Sennbro CJ, Alenius GM, Moritz T et al. Diagnostic properties of metabolic perturbations in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther ; 13 : R Buckley MG, Walters C, Wong WM, Cawley MI, Ren S, Schwartz LB et al. Mast cell activation in arthritis: detection of α - and β -tryptase, histamine and eosinophil cationic protein in synovial fluid. Clin Sci Lond ; 93 : — Goodman MN. Tumor necrosis factor induces skeletal muscle protein breakdown in rats. Am J Physiol ; : E—E Aviña-Zubieta JA, Choi HK, Sadatsafavi M, Etminan M, Esdaile JM, Lacaille D. Risk of cardiovascular mortality in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Arthritis Rheum ; 59 : — Murdaca G, Colombo BM, Cagnati P, Gulli R, Spanò F, Puppo F. Endothelial dysfunction in rheumatic autoimmune diseases. Atherosclerosis ; : — Violi F, Basili S, Nigro C, Pignatelli P. Role of NADPH oxidase in atherosclerosis. Future Cardiol ; 5 : 83— Lavrik IN. Systems biology of death receptor networks: live and let die. Datta S, Kundu S, Ghosh P, De S, Ghosh A, Chatterjee M. Correlation of oxidant status with oxidative tissue damage in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Rheumatol ; 33 : — Ishibashi T. Molecular hydrogen: new antioxidant and anti-inflammatory therapy for rheumatoid arthritis and related diseases. Curr Pharm Des ; 19 : — Park YJ, Kim JY, Park J, Choi JJ, Kim WU, Cho CS. Bone erosion is associated with reduction of circulating endothelial progenitor cells and endothelial dysfunction in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum ; 66 : — Dimitroulas T, Sandoo A, Veldhuijzen van Zanten JJ, Smith JP, Hodson J, Metsios GS et al. Predictors of asymmetric dimethylarginine levels in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: the role of insulin resistance. Scand J Rheumatol ; 42 : — Provan SA, Semb AG, Hisdal J, Stranden E, Agewall S, Dagfinrud H et al. Remission is the goal for cardiovascular risk management in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a cross-sectional comparative study. Ann Rheum Dis ; 70 : — Bradham WS, Ormseth MJ, Oeser A, Solus JF, Gebretsadik T, Shintani A et al. Insulin resistance is associated with increased concentrations of NT-proBNP in rheumatoid arthritis: IL-6 as a potential mediator. Inflammation ; 37 : — Chimenti MS, Graceffa D, Perricone R. Anti-TNFα discontinuation in rheumatoid and psoriatic arthritis: Is it possible after disease remission? Weinblatt ME, Trentham DE, Fraser PA, Holdsworth DE, Falchuk KR, Weissman BN et al. Long- term prospective trial of low-dose methotrexate in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum ; 31 : — Chimenti MS, Ballanti E, Perricone C, Cipriani P, Giacomelli R, Perricone R. Immunomodulation in psoriatic arthritis: focus on cellular and molecular pathways. Maini R St, Clair EW, Breedveld F, Furst D, Kalden J, Weisman M et al. Infliximab chimeric anti-tumour necrosis factor alpha monoclonal antibody versus placebo in rheumatoid arthritis patients receiving concomitant methotrexate: a randomised phase III trial. Lancet ; : — Weinblatt ME, van Riel PL. Targeted therapies: summary clinical trials working group. Ann Rheum Dis ; 65 : iii Wu YT, Tan HL, Huang Q, Sun XJ, Zhu X, Shen HM. zVAD-induced necroptosis in L cells depends on autocrine production of TNFα mediated by the PKC-MAPKs-AP-1 pathway. Cell Death Differ ; 18 : 26— Takata M, Nakagomi T, Kashiwamura S, Nakano- Doi A, Saino O, Nakagomi N et al. Geering B, Simon HU. A novel signaling pathway in TNFα-induced neutrophil apoptosis. Cell Cycle ; 10 : — Christofferson DE, Li Y, Hitomi J, Zhou W, Upperman C, Zhu H et al. A novel role for RIP1 kinase in mediating TNFα production. Cell Death Dis ; 3 : e Conigliaro P, Triggianese P, Perricone C, Chimenti MS, Di Muzio G, Ballanti E et al. Restoration of peripheral blood natural killer and B cell levels in patients affected by rheumatoid and psoriatic arthritis during etanercept treatment. Clin Exp Immunol ; : — Carrillo-de Sauvage MÁ, Maatouk L, Arnoux I, Pasco M, Sanz Diez A, Delahaye M et al. Potent and multiple regulatory actions of microglial glucocorticoid receptors during CNS inflammation. Gonzalez-Gay MA, Gonzalez-Juanatey C, Vazquez-Rodriguez TR, Miranda-Filloy JA, Llorca J. Insulin resistance in rheumatoid arthritis: the impact of the anti-TNF-alpha therapy. Ann N Y Acad Sci ; : — Schultz O, Oberhauser F, Saech J, Rubbert-Roth A, Hahn M, Krone W et al. Effects of inhibition of interleukin-6 signalling on insulin sensitivity and lipoprotein a levels in human subjects with rheumatoid diseases. PLoS One ; 5 : e Preyat N, Rossi M, Kers J, Chen L, Bertin J, Gough PJ et al. Intracellular nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide promotes TNF-induced necroptosis in a sirtuin-dependent manner. Cell Death Differ e-pub ahead of print 22 May Spinelli FR, Metere A, Barbati C, Pierdominici M, Iannuccelli C, Lucchino B et al. Effect of therapeutic inhibition of TNF on circulating endothelial progenitor cells in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Mediators Inflamm — Danninger K, Hoppe UC, Pieringer H. Do statins reduce the cardiovascular risk in patients with rheumatoid arthritis? Int J Rheum Dis ; 17 : — Ballanti E, Perricone C, Di Muzio G, Kroegler B, Chimenti MS, Graceffa D et al. Role of the complement system in rheumatoid arthritis and psoriatic arthritis: relationship with anti-TNF inhibitors. Download references. Department of Experimental Medicine and Surgery, Univeristy of Rome Tor Vergata, Rome, , Italy. You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar. Correspondence to M S Chimenti. Cell Death and Disease is an open-access journal published by Nature Publishing Group. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4. Reprints and permissions. Chimenti, M. et al. The interplay between inflammation and metabolism in rheumatoid arthritis. Cell Death Dis 6 , e Download citation. Received : 16 July Accepted : 29 July Published : 17 September Issue Date : September Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:. Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative. International Journal of Biometeorology Skip to main content Thank you for visiting nature. Download PDF. Subjects Chronic inflammation Metabolism Rheumatoid arthritis Therapeutics. Abstract Rheumatoid arthritis RA is a chronic autoimmune disease characterized by extensive synovitis resulting in erosions of articular cartilage and marginal bone that lead to joint destruction. Facts The elucidation of metabolic pathways in chronic inflammatory conditions, as rheumatoid arthritis RA , give new insights on pathogenesis, clinical features and complications, and treatment outcome. Open Questions Although the autoimmune process in RA depends on the involvement of immune cells, which utilize intracellular kinases to respond to external stimuli, further research efforts are necessary in order to define more specific biomarkers to be detected in the management of that disease. Full size image. Metabolic Changes During Inflammation Metabolism is viewed simply as a mean to generate a store of energy by catabolism, and to generate macromolecules for cell maintenance and growth through anabolic pathways. Figure 2. Inflammation and Metabolism in RA The widespread systemic effects mediated by pro-inflammatory cytokines in RA impact on metabolism. Atherosclerosis and endothelial dysfunction RA pathobiology seems to share some common pathways with atherosclerosis, including endothelial dysfunction ED that is related to underlying chronic inflammation and presents in the early phases of the disease. The Role of the Therapy: Metabolic Effects and New Potential Interventions in RA Treatment The therapy management of RA rests primarily based on the use of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs DMARDs. Table 1 Effects of treatments on metabolic and cardiovascular outcome in rheumatoid arthritis patients Full size table. Table 2 Effects of drugs targeting metabolic and environmental factors on disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis patients Full size table. Conclusions The widespread systemic effects mediated by pro-inflammatory cytokines in RA impact on metabolism. References McInnes IB, Schett G. CAS PubMed Google Scholar Zordan P, Rigamonti E, Freudenberg K, Conti V, Azzoni E, Rovere-Querini P et al. CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Través PG, Pardo V, Pimentel-Santillana M, González-Rodríguez Á, Mojena M, Rico D et al. PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Brennan FM, McInnes IB. CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Raychaudhuri S. CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Remmers EF, Plenge RM, Lee AT, Graham RR, Hom G, Behrens TW et al. CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Plenge RM, Seielstad M, Padyukov L, Lee AT, Remmers EF, Ding B et al. CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Hu R, Chen ZF, Yan J, Li QF, Huang Y, Xu H et al. CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Pedersen M, Jacobsen S, Klarlund M, Pedersen BV, Wiik A, Wohlfahrt J et al. PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Cauwels A, Rogge E, Vandendriessche B, Shiva S, Brouckaert P. CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Tarner IH, Harle P, Muller-Ladner U, Gay RE, Gay S. PubMed Google Scholar Lettieri Barbato D, Aquilano K, Baldelli S, Cannata SM, Bernardini S, Rotilio G et al. CAS PubMed Google Scholar Mihaly SR, Ninomiya-Tsuji J, Morioka S. CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Jongbloed SL, Lebre MC, Fraser AR, Gracie JA, Sturrock RD, Tak PP et al. PubMed Google Scholar Reis AC, Alessandri AL, Athayde RM, Perez DA, Vago JP, Ávila TV et al. CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Yang L, Karin M. CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Shalini S, Dorstyn L, Dawar S, Kumar S. CAS PubMed Google Scholar Su Z, Yang R, Zhang W, Xu L, Zhong Y, Yin Y et al. CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Kotake S, Udagawa N, Takahashi N, Matsuzaki K, Itoh K, Ishiyama S et al. CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Summersgill H, England H, Lopez-Castejon G, Lawrence CB, Luheshi NM, Pahle J et al. CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Steiner G, Tohidast-Akrad M, Witzmann G, Vesely M, Studnicka-Benke A, Gal A et al. CAS Google Scholar Li L, Ng DS, Mah WC, Almeida FF, Rahmat SA, Rao VK et al. CAS PubMed Google Scholar Xu J, Jiang Y, Wang J, Shi X, Liu Q, Liu Z et al. CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Skapenko A, Leipe J, Lipsky PE, Schulze-Koops H. PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Scott DL, Steer S. PubMed Google Scholar Prete M, Racanelli V, Digiglio L, Vacca A, Dammacco F, Perosa F. PubMed Google Scholar Sárvári AK, Doan-Xuan QM, Bacsó Z, Csomós I, Balajthy Z, Fésüs L. PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Gremese E, Ferraccioli G. CAS PubMed Google Scholar Turesson C, Matteson EL. PubMed Google Scholar Gabriel SE, Crowson CS. CAS PubMed Google Scholar Oren P, Farnham AE, Milofsky M, Marnovsky ML. CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar He Z, Liu H, Agostini M, Yousefi S, Perren A, Tschan MP et al. CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Humphries F, Yang S, Wang B, Moynagh PN. CAS PubMed Google Scholar Bennett WE, Cohn ZA. CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Arwadi MS, Newsholme EA. Google Scholar Rodriguez-Prados JC, Través PG, Cuenca J, Rico D, Aragonés J, Martín-Sanz P et al. CAS PubMed Google Scholar Shi LZ, Wang R, Huang G, Vogel P, Neale G, Green DR et al. CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Yin YW, Liao SQ, Zhang MJ, Liu Y, Li BH, Zhou Y et al. PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Dang EV, Barbi J, Yang HY, Jinasena D, Yu H, Zheng Y et al. CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Van der Windt GJ, Everts B, Chang CH, Curtis JD, Freitas TC, Amiel E et al. CAS PubMed Google Scholar Rhee EP, Gerszten RE. CAS PubMed Google Scholar Baron L, Gombault A, Fanny M, Villeret B, Savigny F, Guillou N et al. CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Kim SR, Kim DI, Kim SH, Lee H, Lee KS, Cho SH et al. CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Qin Y, Chen Y, Wang W, Wang Z, Tang G, Zhang P et al. CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Hiebert PR, Wu D, Granville DJ. CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Wang R, Dillon CP, Shi LZ, Milasta S, Carter R, Finkelstein D et al. PubMed Google Scholar Alonso R, Mazzeo C, Rodriguez MC, Marsh M, Fraile-Ramos A, Calvo V et al. CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Li W, Ren G, Huang Y, Su J, Han Y, Li J et al. CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Cencioni MT, Santini S, Ruocco G, Borsellino G, De Bardi M, Grasso MG et al. CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Zeng H, Yang K, Cloer C, Neale G, Vogel P, Chi H. CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Krawczyk C, Holowka T, Sun J, Blagih J, Amiel E, DeBerardinis RJ et al. CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Ewald F, Annemann M, Pils MC, Plaza-Sirvent C, Neff F, Erck C et al. CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Tanner DC, Campbell A, O'Banion KM, Noble M, Mayer-Pröschel M. CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Sanders MG, Parsons MJ, Howard AG, Liu J, Fassio SR, Martinez JA et al. CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Chimenti MS, Tucci P, Candi E, Perricone R, Melino G, Willis AE. CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Priori R, Scrivo R, Brandt J, Valerio M, Casadei L, Valesini G et al. CAS PubMed Google Scholar Kapoor SR, Filer A, Fitzpatrick MA, Fisher BA, Taylor PC, Buckley CD et al. CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Chen X, Gan Y, Li W, Su J, Zhang Y, Huang Y et al. CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Abella V, Scotece M, Conde J, López V, Lazzaro V, Pino J et al. Google Scholar Fabre O, Breuker C, Amouzou C, Salehzada T, Kitzmann M, Mercier J et al. CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Alberti KG, Eckel RH, Grundy SM, Zimmet PZ, Cleeman JI, Donato KA et al. CAS PubMed Google Scholar Crowson CS, Myasoedova E, Davis JM 3rd, Matteson EL, Roger VL, Therneau TM et al. A total of 37 UPF items were categorized into seven food groups, and then the mean daily intake of each of seven UPF groups was divided by the total daily intake of UPF and multiplied by These groups included non-dairy beverages Cola, nectar drink, and instant coffee , cookies—cakes [cookies, biscuit, pastries creamy and non-creamy , cake, pancake, doughnut, industrial bread, toasted bread, noodles, and pasta , dairy beverages [ice cream non-pasteurized , ice cream pasteurized , chocolate milk, and cocoa milk], potato chips—salty snacks [chips crisps , crackers, and cheese puff], processed meat fast foods [burger, sausage, bologna, and pizza], oil sauces margarine, ketchup, and mayonnaise , and sweets jam, rock candy, candies, chocolates, sweets, nogal, sohan, Gaz, and sesame halva The physical activity PA of the participants was also evaluated via the short form of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire IPAQ The normality of data was evaluated using a Kolmogorov—Smirnov test. Chi-square tests and one-way analysis of variance ANOVA and analysis of covariance ANCOVA were used for categorical variables and dietary intake in order to compare the differences among tertiles of NOVA scores. Bonferroni post hoc tests were used to investigate differences between tertiles. Linear regression was also used to investigate the relationship between outcomes and exposure in crude and two adjusted models and the role of inflammatory markers. Model 1 was adjusted for age, energy intake, BMI, physical activity, job status, and supplement intake. In model 2, additional controlling for legumes and vegetables was conducted. Pearson correlation was utilized to discern the association between inflammatory markers, RMR, and NOVA score. All analyses were conducted using Statistical Package for Social Sciences SPSS version 25 software SPSS Inc. As shown in Supplementary Table 1 , according to NOVA screening, most of the UPF intakes were via non-dairy beverages General characteristics of the participants across NOVA score tertiles are shown in Table 1. The mean SD of weight, FFM, and BMI was In addition, the total mean SD of serum levels of hs-CRP, IL-1β, MCP-1, and PAI-1 was 4. A total of women had a moderate income, and were taking dietary supplements. Table 1. Distribution of general variables of the participants among tertiles of UPF intake. The dietary intake of subjects between NOVA tertiles is shown in Table 2. Table 2. Intake of UPF, food groups, and nutrients according to the UPF tertiles in overweight and obese women. According to Table 3 , the mean RMR was not significantly different between the tertiles of NOVA in the crude model. The relationship between the RMR and NOVA score is shown in Table 4. No significant relationship of RMR variables were observed among NOVA groups in crude models. This negative relationship remained after adjusting for all confounders in model 2. Table 4. Association between resting metabolic rate and related variables and UPF intakes. The correlation between inflammatory markers and the RMR variables is shown in Supplementary Table 2. The mediatory role of inflammatory markers on the relationship between UPF intakes and RMR is shown in Supplementary Figure 1. After adjusting for all confounders Table 5 , it was evident that all of the markers may inversely mediate the relationship between the mentioned variables and NOVA scores. Table 5. The association of the mediating effect of inflammatory markers on RMR subcategories between UPF tertiles in overweight and obese women. In this study, we found that with increasing NOVA scores, RMR deviation from the calculated normal RMR was increased, which indicates that with increasing UPF consumption, RMR decreased. In addition, a significant negative association between the RMR, RMR per BMI, and RMR per FFM, with NOVA score was observed after adjusting all confounders. This suggests that all the included markers may inversely mediate the relationship between the mentioned variables and NOVA score. In addition, hs-CRP and MCP-1 also had a possible negative mediatory role in the relationship between NOVA score groups and RMR deviation from normal. High levels of CRP indicate low-grade inflammation that is, often, associated with several non-communicable diseases, including obesity, cardiovascular disease CVD , and diabetes 34 — In a study of adolescent girls in Iran, it was found that there is a positive and significant relationship between adherence to a Western diet and higher serum levels of CRP Western diets contain high amounts of refined grains, snacks, red meats and organ meat, pizza, fruit juices, industrial compote, mayonnaise, sugar, soft drinks, sweets, and desserts. On the other hand, the consumption of fruits and vegetables is inversely correlated with CRP levels, which is comparable to the findings in our study, where fruit and vegetable intake decreased with increasing NOVA scores, and the amount of hs-CRP increased Findings of Lopes et al. suggest that a positive association between excess intake of UPFs and CRP levels in women may be mediated by adipocytes The positive association between the consumption of UPFs and the CRP seen in women may be partly explained by the greater accumulation of body fat in women as BMI is strongly associated with CRP levels in women 40 , The consumption of UPFs is known to lead to the overproduction of reactive oxygen species and thereby enhances inflammation by increasing hs-CRP levels and decreasing adiponectin 42 — 44 ; indeed, the mechanism that may justify the mediatory role of hs-CRP on the relationship between UPFs and RMR may be related to insulin. In the presence of obesity, CRP levels increase 45 , 46 , and elevated levels are associated with inflammation and insulin resistance However, insulin sensitivity is inversely related to the RMR 47 , which indicates that with consumption of UPFs, hs-CRP levels, inflammation, and insulin resistance increase, which has a decreasing effect on the RMR. In a group of healthy individuals with normal weight and overweight, the association between RMR and hs-CRP levels, indicative of inflammation, was investigated, and the authors reported that sex significantly affects the age-related changes in body composition, in addition to changes in body composition—REE relationship From a biological perspective, IL-6, which is expressed in adipose tissue, stimulates the production of CRP in the liver and leads to higher levels of circulating hs-CRP. In addition, adipocytes produce and secrete fewer pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines, especially enlarged adipocytes, which may be associated with impaired glucose—insulin homeostasis and impaired energy metabolism 49 — The products secreted by adipose tissue affect systemic metabolism by inflammatory cytokines, leptin, and PAI-1 In fact, some of the nutritional properties of UPFs, such as high energy density, high glycemic load, and high content of saturated and trans fats, may stimulate inflammation by increasing oxidative stress The results of Yunsheng et al. show that dietary fiber may have protective effects against hs-CRP 54 , while in a recent review article 55 , King et al. suggested that dietary fiber reduced lipid oxidation, which, in turn, was associated with reduced inflammation. Dietary fiber also helps maintain a healthy gut environment and natural flora, which help prevent inflammation 55 ; indeed, in our study, with the increasing NOVA score and increasing CRP, the amount of dietary fiber intake decreased. The study by Bibiloni et al. showed an association between omega-3 and PIA-1 PUFAs in healthy women PUFA intake in the Western diet mainly includes n-6 PUFA mainly linoleic acid and arachidonic acid , with a ratio of n6:n-3 ranging from 10 to Arachidonic acid AA is released from the membrane through the lipoxygenase pathway to pro-inflammatory eicosanoids, which are involved in inflammatory activation When n-3 PUFA intake is higher, eicosapentaenoic acid EPA and docosahexaenoic acid DHA partially replace AA in the cell membrane; thus, fewer biologically active substances are formed, and the balance of n-6 and n-3 eicosanoids changes to compounds with less inflammatory activity Another study, by Miller and colleagues, showed that total fiber intake was inversely related to PAI-1, while insoluble fiber was inversely associated with PAI-1 and MCP-1 in overweight women In our study, with the increasing NOVA score, the intake of linolenic acid and dietary fiber decreased, and the amount of hs-CRP increased, although no significant difference was seen in MCP-1 and PIA The mechanism of the mediatory role of MCP-1, like hs-CRP, may also be related to insulin secretion and resistance. MCP-1 secretion is stimulated by tumor necrosis factor α TNFα , IL-6, and IL-1β, which are secreted from adipose tissue 61 , Elevated MCP-1 levels are associated with insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes T2DM 63 , 64 , and as noted earlier, insulin resistance is inversely related to RMR However, MCP-1 and hs-CRP had mediating effects on the association between RMR and UPF, which could be due to differences in the rate of inflammation and fiber intake total, soluble, and insoluble , as compared with previous studies. In a randomized controlled trial performed by Hall et al. Participants consumed more carbohydrates and fats and gained weight and body fat. The authors also showed that eating UPFs reduced the secretion of the hunger hormone ghrelin and also increased the level of the satiety hormone PYY YY peptide Thus, UPFs may more efficiently regulate and stimulate biological mechanisms of hunger and satiety control than processed foods. The authors also asserted that with the unprocessed diet, a decrease in the inflammatory biomarker of hs-CRP was observed and that inflammation may be associated with satiety signals in animal studies Evidence is emerging regarding the mechanisms that strengthen the link between UPFs and adverse health outcomes. The mechanisms proposed are as follows: poor nutritional profile, UPFs are rich in sodium, added sugars, trans fats, and replace unprocessed foods in the diet 66 — 70 , decrease in intestinal and brain satiety signal due to changes in physical properties caused by food processing and higher glycemic load 71 — 74 , carcinogens formed during high-temperature cooking acrylamide 75 , 76 , and inflammatory responses associated with cellular nutrients and industrial food additives, increased intestinal permeability, and dysbiosis of the intestinal microflora 65 , 77 , Carbohydrate metabolism is more energy-intensive than fat metabolism, while protein metabolism requires the most energy 79 — Processed foods have lower nutrient densities less content and variety of nutrients per calorie than whole foods, where extra simple carbohydrates 82 — 84 and less dietary fiber that make them chemically and structurally simple and digestible 82 , 83 , All these reduce the volume of meals and reduce satiety, which consequently lead to increased daily caloric intake 31 — 39 , which is associated with obesity and systemic inflammation 86 — The strengths of this study are the use of an FFQ questionnaire, which has been specifically validated in the Iranian population. Nevertheless, residual confounding related to recall bias must be acknowledged. Examining this association in one gender and only in Tehran represent limitations of this study because these results cannot be extrapolated to the entire Iranian population and all individuals. The cross-sectional design of this study precludes causal inferences being made. In addition, using BIA may overestimate lean body mass. Ultra-processed foods may be related with changes in the production and secretion of cytokines and inflammatory factors and, ultimately, cause inflammation and reduced RMRs. A negative association between the RMR, RMR per BMI, and RMR per FFM with the NOVA score was observed in the present study. UPF intake is likely related with the RMR, RMR per BMI, and RMR per FFM, mediated by the production of hs-CRP, PAI-1, MCP-1, and IL-1β. hs-CRP and MCP-1 levels also had a possible negative mediatory role in the relationship between NOVA score groups and RMR deviation from normal. Given the novel evidence provided, further work, in the form of interventional studies, is needed in this area. The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Tehran University of Medical Sciences and Health Services. NB and FS designed the project. FS collected the samples and analyzed the data. NB and SN wrote the manuscript. FS, CC, and NB reviewed and edited the manuscript. KM conducted the research and had primary responsibility for the final content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. The Tehran University of Medical Sciences and Health Services funded and supported the present study Grant ID: We thank the study participants for their cooperation and assistance in physical examinations and CC who did language editing. The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher. Supplementary Figure 1 The mediatory role of inflammatory markers on the relationship between UPF intakes and RMR. RMR, resting metabolic rate; LED, low energy density; HED, high energy density; UPFs, ultra-processed foods; PA, physical activity; WC, waist circumference; WHR, waist-to-hip ratio; BMI, body mass index; PAI-1, plasminogen activator-1; IL-6, interleukin-6; PUFA, polyunsaturated fatty acids; MCP-1, monocyte chemoattractant protein; hs-CRP, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; FBS, fasting blood sugar; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglyceride; IC, indirect calorimetry; BSA, body surface area; FFM, free fat mass; FFQ, food frequency questionnaire; IPAQ, the International Physical Activity Questionnaire; METs, metabolic equivalents; ANOVA, one-way analysis of variance; ANCOVA, analysis of covariance. Kaplan MS, Huguet N, Newsom JT, McFarland BH, Lindsay J. Prevalence and correlates of overweight and obesity among older adults: findings from the Canadian national population health survey. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. doi: PubMed Abstract CrossRef Full Text Google Scholar. Astrup A, Buemann B, Toubro S, Ranneries C, Raben A. Low resting metabolic rate in subjects predisposed to obesity: a role for thyroid status. Am J Clin Nutr. Song N, Liu F, Han M, Zhao Q, Zhao Q, Zhai H, et al. Prevalence of overweight and obesity and associated risk factors among adult residents of northwest China: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. McMurray RG, Soares J, Caspersen CJ, McCurdy T. Examining variations of resting metabolic rate of adults: a public health perspective. Med Sci Sports Exerc. Buchholz AC, Rafii M, Pencharz PB. Is resting metabolic rate different between men and women. Br J Nutr. Schrack JA, Knuth ND, Simonsick EM, Ferrucci L. J Am Geriatr Soc. De Jonge L, Bray GA, Smith SR, Ryan DH, De Souza RJ, Loria CM, et al. Effect of diet composition and weight loss on resting energy expenditure in the POUNDS LOST study. Van Marken WD, Lichtenbelt RP, Westerterp MKR. The effect of fat composition of the diet on energy metabolism. Z Ernahrungswiss. Karl JP, Roberts SB, Schaefer EJ, Gleason JA, Fuss P, Rasmussen H, et al. Effects of carbohydrate quantity and glycemic index on resting metabolic rate and body composition during weight loss. Gibney MJ. Ultra-processed foods : definitions and policy issues. Curr Dev Nutr. Elizabeth L, Machado P, Zinöcker M, Baker P, Lawrence M. Ultra-processed foods and health outcomes: a narrative review. Sung H, Park JM, Oh SU, Ha K, Joung H. Consumption of ultra-processed foods increases the likelihood of having obesity in Korean women. Li M, Shi Z. Costa CDS, Faria FR, Gabe KT, Sattamini IF, Khandpur N, Leite FHM, et al. Nova score for the consumption of ultra-processed foods description and performance evaluation in Brazil. Rev Saude Publica. Barr SB, Wright JC. Postprandial energy expenditure in whole-food and processed-food meals: implications for daily energy expenditure. Food Nutr Res. Hall KD, Ayuketah A, Brychta R, Cai H, Cassimatis T, Chen KY, et al. Ultra-Processed diets cause excess calorie intake and weight gain: an inpatient randomized controlled trial of ad libitum food intake. Cell Metab. Smiljanec K, Mbakwe AU, Ramos-Gonzalez M, Mesbah C, Lennon SL. Morais AHDA, Passos TS, Vale SHDL, Maia JKDS, Maciel BLL. Obesity and the increased risk for COVID mechanisms and nutritional management. Nutr Res Rev. Grag MK, Dutta MK, Mahalle N. Adipokines adiponectin and plasminogen activator inhhibitor-1 in metabolic syndrome. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. Nestares T, Martín-Masot R, Flor-Alemany M, Bonavita A, Maldonado J, Aparicio VA. Influence of ultra-processed foods consumption on redox status and inflammatory signaling in young celiac patients. Aguayo-Patrón SV, Calderón de la Barca AM. Old fashioned vs. Ultra-processed-based current diets: possible implication in the increased susceptibility to type 1 diabetes and celiac disease in childhood. Bujtor M, Turner AI, Torres SJ, Esteban-Gonzalo L, Pariante CM, Borsini A. Associations of dietary intake on biological markers of inflammation in children and adolescents: a systematic review. Banna JC, McCrory MA, Fialkowski MK, Boushey C. Examining plausibility of self-reported energy intake data: considerations for method selection. Front Nutr. Gutch M, Kumar S, Razi SM, Gupta K, Gupta A. Lam YY, Ravussin E. Indirect calorimetry: an indispensable tool to understand and predict obesity. Eur J Clin Nutr. Livingston EH, Kohlstadt I. Obes Res. Cunningham JJ. Body composition and resting metabolic rate: the myth of feminine metabolism. Askarpour M, Yarizadeh H, Djafarian K, Mirzaei K. Association between the dietary inflammatory index and resting metabolic rate per kilogram of fat-free mass in overweight and obese women. J Iran Med Counc. Google Scholar. Hosseini B, Mirzaei K, Maghbooli Z, Keshavarz SA, Hossein-Nezhad A. Compare the resting metabolic rate status in the healthy metabolically obese with the unhealthy metabolically obese participants. J Nutr Intermed Metab. CrossRef Full Text Google Scholar. Mirmiran P, Hosseini-Esfahani F, Jessri M, Mahan LK, Shiva N, Azizi F. Does dietary intake by Tehranian adults align with the dietary guidelines for Americans? Observations from the Tehran lipid and glucose study. J Heal Popul Nutr. Morgan KJ, Zabik ME, Stampley GL. The role of breakfast in diet adequacy of the U. adult population. J Am Coll Nutr. Edalati S, Bagherzadeh F, Jafarabadi MA, Ebrahimi-Mamaghani M. Higher ultra-processed food intake is associated with higher DNA damage in healthy adolescents. Craig CL, Marshall AL, Sjöström M, Bauman AE, Booth ML, Ainsworth BE, et al. International physical activity questionnaire: Country reliability and validity. Wärnberg J, Nova E, Moreno LA, Romeo J, Mesana MI, Ruiz JR, et al. Inflammatory proteins are related to total and abdominal adiposity in a healthy adolescent population: the AVENA study. Ridker PM. High-sensitivity C-reactive protein: potential adjunct for global risk assessment in the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Clinical Application of C-Reactive Protein for Cardiovascular Disease Detection and Prevention. Sai Ravi Kiran B, Mohanalakshmi T, Srikumar R, Prabhakar Reddy E. C-reactive protein and other markers of inflammation in the prediction of cardiovascular disease in diabetes. Int J Res Pharm Sci. Khayyatzadeh SS, Bagherniya M, Fazeli M, Khorasanchi Z, Bidokhti MS, Ahmadinejad M, et al. A Western dietary pattern is associated with elevated level of high sensitive C-reactive protein among adolescent girls. Eur J Clin Invest. Lopes AEDSC, Araújo LF, Levy RB, Barreto SM, Giatti L. Association between consumption of ultra-processed foods and serum c-reactive protein levels: cross-sectional results from the ELSA-Brasil study. Sao Paulo Med J. Rudnicka AR, Rumley A, Whincup PH, Lowe GD, Strachan DP. Sex differences in the relationship between inflammatory and hemostatic biomarkers and metabolic syndrome: British Birth Cohort. J Thromb Haemost. Ahmadi-Abhari S, Luben RN, Wareham NJ, Khaw KT. Distribution and determinants of C-reactive protein in the older adult population: European prospective investigation into cancer-norfolk study. |

| Metabolic syndrome - Symptoms & causes - Mayo Clinic | Andersson, D. Redesigned Patient Portal. Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Cinti, S. Nutr Res Rev. Managing your diet and exercise schedule may not be enough, as inflammation may be continuously hindering your weight loss efforts. Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar. |

Es ist die Bedingtheit

die Maßgebliche Antwort, wissenswert...

ähnlich gibt es etwas?

Ich denke, dass Sie sich irren. Geben Sie wir werden es besprechen.

Und was, wenn uns, diese Frage von anderem Standpunkt anzuschauen?