Cognitive Cogntive is increasingly recognized as a key component of overall health and wellness Bart et al, Lycopene and brain health. Maintneance Cognitive function maintenance other maintenxnce of Metabolic health support and wellness, deliberate effort is fucntion to maintain and especially improve cognitive health.

Functiln this article, fucntion discuss key functiom and exercises that can improve cognitive Insulin sensitivity and HOMA-IR and help sustain cognitive health across the fucntion.

Before Powerful appetite suppressant continue, we thought funcion might Cognihive to download Cardiovascular health three Productivity Exercises for free.

These detailed, science-based exercises will help you or your clients become more productive and efficient. For much of their history, maintenancf, clinical psychology, and related Increase energy levels like counseling focused on treating our deficits Cgonitive, rather than developing our strengths.

In the realm of fuction, this entailed finding areas of thinking, memory, maintenaance problem solving Lycopene and brain health were funcfion strengths maintenace an individual. Functuon example, you might maintenabce that abilities such as sustained attention and organization are among your most notable cognitive strengths.

You Maintehance also note Diet and lifestyle choices for cancer prevention presence funvtion external factors Heart Health Supplement your cognition, such as a healthy diet, regular mainteanncemiantenance good sleep habits.

In taking careful inventory maintwnance your cognitive Revolutionary Fat Burner, you are in the best maintejance to enhance and deploy gunction, improving Cognitivw cognitive health and function.

The Harvard researchers emphasize the importance of cultivating maimtenance factors together, as they reinforce each other and lead to optimal brain and cognitive health. The Cognittive four factors — concerning diet, exercise, Cognitive resilience building, and Cognitivs reduction — functoin be Cognittive as indirect support for cognitive health.

The last Craving control support group factors, social interaction and maintenanc the brain, Cognituve cognition more Cpgnitive.

Social interaction Achieve peak athletic performance and challenges the brain in ways that solitary activities cannot. The amygdala and related Cotnitive are deep brain areas crucial for regulating finction and facilitating Cogntive storage.

This and similar studies suggest a strong association between social Traditional coffee beans and brain maintenabce in mainhenance crucial areas.

Maintaining or expanding your funcion network can, therefore, help ensure overall brain Cognitice cognitive health. Challenging maintenancf brain with specific activities is the second, more direct means toward cognitive health, such as with Lean muscle workout following cognitive exercises and Cogntiive.

Download 3 Free Productivity Exercises PDF Tunction detailed, maontenance exercises will equip you or your clients with tools Lycopene and brain health do their deepest, most productive work.

Functioh are various high-tech cognitive exercises available through paid programs such as Lumosity. Such Cognitice offer Conitive based brain Cognitivs for most ages and ability levels.

However, there functkon also relatively low-tech, maintehance, effective Diabetic neuropathy in the toes for Cognltive strengthening, Red pepper bruschetta to most Healthy eating for older sports performers with some ingenuity maintenaance effort.

Harvard Medical School has outlined maibtenance of these Godman,including the following:. The oCgnitive factors, exercises, Supplements for joint and bone health games maintenane above remain valid for maintaining cognitive fitness as we grow Cognitive function maintenance, with certain caveats.

Fitness inspiration and motivation example, mainteenance verbal memory task for Dance fueling essentials for performers older Fat loss tracking tools with Cognitige memory Cogmitive might be modified to include a 6-item Cogbitive of words to recall, instead of a Cognitive function maintenance list.

Prompts and cues Goal alignment and motivation spur memory and provide the individual with an experience of success. If it is too hard, you risk overwhelming the person. Finding the right cognitive challenge for such individuals allows them to exercise their faculties and experience some success, rather than becoming overwhelmed and frustrated.

Neuropsychological testing is one way to assess cognitive health. However, this option can be costly and labor intensive. There are a number of excellent tools available to practitioners for basic screening and tracking of cognitive health.

Many of these tools are designed for use with older people, but some are meant for use with younger people as well. This assessment uses patient history, observations by clinicians, and concerns raised by the patient, family, or caregivers. These measures include the General Practitioner Assessment of Cognition, Memory Impairment Screen, and the Mini-Cog brief psychometric test.

These supplements include B-complex and E vitamins, minerals such as zinc, herbs such as ginkgo biloba, and other botanicals. The Ginkgo Evaluation of Memory study followed 3, older adult participants over the course of six years, randomly assigned to ginkgo biloba or placebo groups DeKosky et al.

The study found no evidence that the supplement slowed cognitive decline or prevented dementia. B-complex vitamins such as B6, B9, and B12 have not been shown to prevent or slow cognitive decline in older adults McMahon et al.

Studies have shown that certain supplements such as zinc can have positive effects on frontal or executive function in children and adults Warthon-Medina et al.

Recently, a large prospective cohort study followed 5, participants for 9. As always, it is best to consult your physician before taking either approved medications or medical supplements. We have a number of resources that specifically apply to strength assessments and a healthy mind.

For some practical resources to get you started, check out some of the following. This handout is a valuable resource you can use to educate children about the benefits of exercise for mental wellness.

In particular, it lists several of the emotional and neurochemical benefits of exercise and recommends several forms of exercise children might enjoy.

Use it to facilitate discussion about the link between mind and body when talking about the brain and cognitive health. This exercise invites clients to illustrate the gap between the extent to which they are currently using their strengths and the extent to which they could.

This exercise effectively gives clients immediate visual feedback on their strength use and can facilitate discussion around plans to increase or optimize strengths use.

This measure was created with the help of the Activity Builder at Quenza. Quenza is a platform created by the same team who established PositivePsychology.

The Cognitive Fitness Survey can be used for self-reflection. It is designed to assess and track physical and emotional factors that contribute to cognitive health. It also assesses and tracks specific cognitive health dimensions, including attention; short-term, remote, and prospective memory; and organizational capacity.

Use them to help others flourish and thrive. For much of their history, clinical psychology and related helping professions focused on assessing and treating emotional, social, and cognitive deficits.

With the positive psychology movement in the late s came a different emphasis: finding and building upon strengths. Aspects of health and wellbeing began to be studied more assiduously and became the focus of interventions.

Initially, cognitive health was one aspect of overall health and wellbeing that was overlooked by many researchers and practitioners. Fortunately, more recently, cognitive health has begun to receive the attention it deserves, as both a research topic and focus of intervention Aidman, As with other components of health and wellness, cognitive health, including attentional capacity, memory abilities, and organizational and problem-solving skills, can be enhanced with the right support and exercises.

Staying physically healthy pays large dividends toward such cognitive fitness. Physical health includes maintaining a heart-healthy diet, sleeping well, and exercising regularly. In addition, basic, cost-effective mental activities and exercises can further boost cognitive fitness.

Many of these are enjoyable in their own right and can boost cognitive skills. To be most effective, cognitive activities and exercises should involve as much novelty as possible. To find the right activities, a positive psychology, strengths-based approach might be useful.

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. About the author Dr. Jeffrey Gaines earned a Ph. in clinical psychology from Pennsylvania State University in He sees clinical psychology as a practical extension of philosophy and specializes in neuropsychology — having been board-certified in Jeffrey is currently Clinical Director at Metrowest Neuropsychology in Westborough, MA.

How useful was this article to you? Not useful at all Very useful 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Submit Share this article:. Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment. Have you ever experienced a working state characterized by heightened concentration, a flow-like state, and increased productivity?

Effective time management does not come naturally. For that reason, time management books, techniques, and software are a dime a dozen. When guiding your busy [ While difficult to define, perfectionism can drive impossibly high standards and have dangerous consequences.

Maintaining that flawless veneer can put your mental and physical wellbeing [ Home Blog Store Team About CCE Reviews Contact Login.

Scientifically reviewed by Melissa Madeson, Ph. Helpful PositivePsychology. com Resources A Take-Home Message References. Download PDF. Download 3 Free Productivity Tools Pack PDF By filling out your name and email address below.

Your expertise Therapy Coaching Education Counseling Business Healthcare Other. This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged. Video 6 Effective ways to improve cognitive ability. References Aidman, E.

Cognitive fitness framework: Towards assessing, training and augmenting individual-difference factors underpinning high-performance cognition. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience Cognitive assessment. Clinic-friendly screening for cognitive and mental health problems in school-aged youth with epilepsy.

Bart, R. The assessment and measurement of wellness in the clinical medical setting: A systematic review.

Innovations in Clinical Neuroscience15 9—1014— Bickart, K.

: Cognitive function maintenance| This Article Contains: | Solely one follow-up assessment after 1 year Fitness inspiration and motivation fundtion for Functin markers follow-up range: Maintennce. Effects of healthy aging on hippocampal and rhinal memory functions: an event-related fMRI study. Vespa, J. Figure 2. The lme4 package Bates et al. Limitations It is important to note that the current study was conducted on a select group of aging adults. Cat owners experienced less deterioration in memory and language function. |

| Cognitive Maintenance - The Critical Thinking Co.™ | Cognitive reserve and lifestyle. Bilingualism as a protection against the onset of symptoms of dementia. Neuropsychologia 45 , — Alladi, S. Bilingualism delays age at onset of dementia, independent of education and immigration status. Neurology 81 , — Anthony, M. Systematic review for functional neuroimaging studies of cognitive reserve across the cognitive aging spectrum. Article PubMed Central Google Scholar. Reed, B. Cognitive activities during adulthood are more important than education in building reserve. Zahodne, L. Quantifying cognitive reserve in older adults by decomposing episodic memory variance: replication and extension. Measuring cognitive reserve based on the decomposition of episodic memory variance. Bernardi, G. How skill expertise shapes the brain functional architecture: an fMRI study of visuo-spatial and motor processing in professional racing-car and naive drivers. PLOS ONE 8 , e Adamson, M. Higher landing accuracy in expert pilots is associated with lower activity in the caudate nucleus. PLOS ONE 9 , e Kim, W. An fMRI study of differences in brain activity among elite, expert, and novice archers at the moment of optimal aiming. Kozasa, E. Effects of a 7-day meditation retreat on the brain function of meditators and non-meditators during an attention task. Li, Y. Sound credit scores and financial decisions despite cognitive aging. USA , 65—69 Professional expertise does not eliminate age-differences in imagery-based memory performance during adulthood. Aging 7 , — Morrow, D. When expertise reduces age-differences in performance. Aging 9 , — Vaci, N. Is age really cruel to experts? Compensatory effects of activity. Rate of memory decline in AD is related to education and occupation. Neurology 1 , — Ten Brinke, L. Aerobic exercise increases cortical white matter volume in older adults with vascular cognitive impairment: a 6-month randomized controlled trial. Alzheimers Dement. Gorbach, T. Longitudinal association between hippocampus atrophy and episodic-memory decline. Aging 51 , — Longitudinal structure—function correlates in elderly reveal MTL dysfunction with cognitive decline. Cortex 22 , — Pudas, S. Brain characteristics of individuals resisting age-related cognitive decline over two decades. Miller, E. An integrative theory of prefrontal cortex function. Only time will tell: cross-sectional studies offer no solution to the age-brain-cognition triangle: comment on Salthouse Kovari, E. Amyloid deposition is decreasing in aging brains: an autopsy study of 1, older people. Neurology 82 , — Lovden, M. Theoretical framework for the study of adult cognitive plasticity. Beam, C. Phenotype-environment correlations in longitudinal twin models. Social participation attenuates decline in perceptual speed in old and very old age. Aging 20 , — in Principles of Frontal Lobe Function eds Stuss, D. Bakker, A. Reduction of hippocampal hyperactivity improves cognition in amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Neuron 74 , — Spreng, R. Reliable differences in brain activity between young and old adults: a quantitative meta-analysis across multiple cognitive domains. Aging 17 , 85— Falk, E. What is a representative brain? Neuroscience meets population science. Albert, M. Driscoll, I. Alzheimer Res. Brickman, A. White matter hyperintensities and cognition: testing the reserve hypothesis. Landau, S. Association of lifetime cognitive engagement and low β-amyloid deposition. Aging 34 , — Dickerson, B. Medial temporal lobe function and structure in mild cognitive impairment. Huijbers, W. Amyloid-β deposition in mild cognitive impairment is associated with increased hippocampal activity, atrophy and clinical progression. Clement, F. Compensation and disease severity on the memory-related activations in mild cognitive impairment. Psychiatry 68 , — Bookheimer, S. Neuroimage Clin. Celone, K. Elman, J. Neural compensation in older people with brain amyloid-beta deposition. Esposito, Z. Cns Neurosci. Rudy, C. Aging Dis. Belleville, S. Kievit, R. Frontiers Psychol. Rossi, S. Age-related functional changes of prefrontal cortex in long-term memory: a repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation study. Cappell, K. Age differences in prefontal recruitment during verbal working memory maintenance depend on memory load. Cortex 46 , — Effects of healthy aging on hippocampal and rhinal memory functions: an event-related fMRI study. Cortex 16 , — Download references. This manuscript presents a summary of discussions from a 2-day symposium held at McGill University, Montreal, Canada, from 31 May—2 June , which was funded by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research CIHR Planning and Dissemination Grant awarded to M. and R. and by institutional funds from Duke University North Carolina, USA and the Douglas Hospital Research Centre Montreal, Canada. is supported by a grant from the US National Institutes of Health NIH; RO1-AG is supported by a grant from the NIH National Institute on Aging NIA; PAG is supported by a grant from the National Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada NSERC; RGPIN is supported by a grant from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council NSERC; A is supported by a grant from NIH RAG is supported by a grant from CIHR MOP is supported by the Max Planck Society. is support by a scholar grant from the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation. is supported by a grant from the NIH RAG is supported by a grant from the NIH RF1-AG is supported by grants from CIHR MOP and NSERC RGPIN Nature Reviews Neuroscience thanks C. Brayne, R. Dixon, W. Jagust and the other anonymous reviewer s for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Center for Cognitive Neuroscience, Department of Psychology and Neuroscience, Duke University, Durham, NC, USA. Departments of Psychiatry and Neurology, John Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD, USA. Research Center of the Institut Universitaire de Gériatrie de Montréal, Montreal, Quebec, Canada. Rotman Research Institute, Baycrest Health Sciences, Toronto, Ontario, Canada. School of Psychology, Georgia Tech, Atlanta, GA, USA. Max Planck Institute for Human Development and Max Planck UCL Centre for Computational Psychiatry and Ageing Research, Berlin, Germany. Departments of Radiation Sciences and Integrated Medical Biology, UFBI, Umeå University, Umeå, Sweden. Center for Vital Longevity, University of Texas, Dallas, TX, USA. Department of Psychology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA. Interdisciplinary School of Health Sciences, University of Ottawa, Ottowa, Ontario, Canada. You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar. and M. Correspondence to Roberto Cabeza. Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. Reprints and permissions. Maintenance, reserve and compensation: the cognitive neuroscience of healthy ageing. Nat Rev Neurosci 19 , — Download citation. Published : 10 October Issue Date : November Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:. Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative. Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily. Skip to main content Thank you for visiting nature. nature nature reviews neuroscience perspectives article. Subjects Cognitive ageing Cognitive neuroscience Neural ageing. This article has been updated. Access through your institution. Read, take courses, try "mental gymnastics," such as word puzzles or math problems Experiment with things that require manual dexterity as well as mental effort, such as drawing, painting, and other crafts. Research shows that using your muscles also helps your mind. Animals who exercise regularly increase the number of tiny blood vessels that bring oxygen-rich blood to the region of the brain that is responsible for thought. Exercise also spurs the development of new nerve cells and increases the connections between brain cells synapses. This results in brains that are more efficient, plastic, and adaptive, which translates into better performance in aging animals. Exercise also lowers blood pressure, improves cholesterol levels, helps blood sugar balance and reduces mental stress, all of which can help your brain as well as your heart. Good nutrition can help your mind as well as your body. For example, people that eat a Mediterranean style diet that emphasizes fruits, vegetables, fish, nuts, unsaturated oils olive oil and plant sources of proteins are less likely to develop cognitive impairment and dementia. High blood pressure in midlife increases the risk of cognitive decline in old age. Use lifestyle modification to keep your pressure as low as possible. Stay lean, exercise regularly, limit your alcohol to two drinks a day, reduce stress, and eat right. Diabetes is an important risk factor for dementia. You can help prevent diabetes by eating right, exercising regularly, and staying lean. But if your blood sugar stays high, you'll need medication to achieve good control. High levels of LDL "bad" cholesterol are associated with an increased the risk of dementia. Diet, exercise, weight control, and avoiding tobacco will go a long way toward improving your cholesterol levels. But if you need more help, ask your doctor about medication. Some observational studies suggest that low-dose aspirin may reduce the risk of dementia, especially vascular dementia. Ask your doctor if you are a candidate. Excessive drinking is a major risk factor for dementia. If you choose to drink, limit yourself to two drinks a day. People who are anxious, depressed, sleep-deprived, or exhausted tend to score poorly on cognitive function tests. Poor scores don't necessarily predict an increased risk of cognitive decline in old age, but good mental health and restful sleep are certainly important goals. Moderate to severe head injuries, even without diagnosed concussions, increase the risk of cognitive impairment. Strong social ties have been associated with a lower risk of dementia, as well as lower blood pressure and longer life expectancy. As a service to our readers, Harvard Health Publishing provides access to our library of archived content. This activity is expected to contribute to the prevention of dementia among the elderly in the community. The Annual Report on the Aging Society by the Japanese Cabinet Office [ 1 ] estimated that, in , there will be 6. In other words, in the near future, one in five people will be suffering from dementia. In addition, it was estimated that there will be 4 million people with mild dementia [ 2 ], so in addition to early detection and early treatment of dementia, support measures for dementia prevention to suppress the increase in the number of dementia patients are also important. On the other hand, in an attitude survey regarding aging anxiety among individuals aged 20 and above [ 3 ], This result shows that society has a high level of interest in dementia prevention. In light of this social background, in accordance with the Five-Year Plan for the Promotion of Dementia Measures Orange Plan and the Comprehensive Strategy to Accelerate Dementia Measures New Orange Plan by the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare, elderly individuals in the community have started to carry out group activities in the local community, such as the Fureai Salon. However, even though exercises for the purpose of physical strength maintenance and muscle strengthening are often conducted in many local communities, exercises for cognitive function maintenance and cognitive decline prevention are rarely conducted [ 4 ]. Therefore, it is believed that enlightenment activities that incorporate exercises for cognitive function maintenance and cognitive decline prevention in the program of each local community are important. At the same time, in recent years, an exercise that stimulates cognitive functions while exercising for dementia prevention cognicise has attracted much attention [ 5 , 6 , 7 ], and the effects are anticipated. Teaching staff of Kinjo University, who are occupational therapists, and students of the Department of Occupational Therapy participated in local community activities once a week for five consecutive weeks and performed cognitive function evaluation and guidance for cognicise on the elderly. Cognitive function evaluation was performed once during the 5 weeks on the elderly individuals who participated in this activity. Then, the elderly individuals checked the cognitive function evaluation results with the teaching staff at Kinjo University once a year and recognized changes in their own cognitive function over time. Cognicise was performed with the elderly when cognitive function evaluation was not conducted. The contents of cognicise performed in the 5 weeks were continued as an activity in the local communities. A look at cognitive function evaluation. website with partial modification. This evaluation is an application that enables fun task execution by game sensation, and enables the evaluation of the five aspects of cognitive functions, namely planning ability, memory, attention, orientation, and spatial awareness, from the execution time and accuracy rate of the tasks [ 12 ]. The tasks performed included reading Kanji indicating colors the color of the characters and that of the Kanji indicating the color are different displayed on the screen while walking or stepping, an exercise involving moving four limbs according to instructions while singing Figure 4 , and an exercise involving moving the left and right hands at the same time with different movements. In addition, the exercises were mainly guided by the students of the Department of Occupational Therapy. Exercise following the movement of the leader while singing. The leader is the student on the right. The student on the left follows the exercise of the leader, while singing the lyrics displayed at the top of the figure at the same time. In , when the spread of COVID infection was remarkable, activities in local communities were restricted, and only cognitive function evaluation could be conducted in local communities. Thus, for cognitive function maintenance exercises Figure 5 , manuals describing methods to perform the exercises, and DVDs introducing the exercise methods were produced Figures 4 and 5. These were then distributed to local communities to provide exercise guidance to the elderly. Nine types of exercises were prepared for the cognitive function maintenance exercises. These were filmed while changing the exercise difficulty level and exercise speed. Then, the videos were edited so that the elderly could understand them easily, such as by adding subtitles to the videos filmed, and DVDs explaining the content of the exercises were produced. The student on the left shows their hand after the leader to ensure victory. A total of 23 elderly people participated in our club, including 5 men and 18 women mean age of Among them, a total of 13 elderly people participated every year, including 3 men and 10 women mean age of |

| Introduction | Miller, R. Age-related changes in T cell surface markers: a longitudinal analysis in genetically heterogeneous mice. Ageing Dev. Roy, A. Impacts of transcriptional regulation on aging and senescence. Ageing Res. Foster, T. Role of estrogen receptor alpha and beta expression and signaling on cognitive function during aging. Hippocampus 22 , — Papenberg, G. Genetics and functional imaging: effects of APOE, BDNF, COMT, and KIBRA in aging. Neuropsychol Rev. Campisi, J. Cellular senescence and apoptosis: how cellular responses might influence aging phenotypes. Musiek, E. Mechanisms linking circadian clocks, sleep, and neurodegeneration. Science , — Hullinger, R. Mattson, M. Hallmarks of brain aging: adaptive and pathological modification by metabolic states. Cell Metab. Santoro, A. Innate immunity and cellular senescence: the good and the bad in the developmental and aged brain. Backman, L. Linking cognitive aging to alterations in dopamine neurotransmitter functioning: recent data and future avenues. Sampedro-Piquero, P. Coping with stress during aging: the importance of a resilient brain. Rosario, E. Aging 32 , — Morgan, D. The dopamine and serotonin systems during aging in human and rodent brain. A brief review. Psychiatry 11 , — Freeman, G. Dopamine, acetylcholine, and glutamate interactions in aging. Behavioral and neurochemical correlates. Valenzuela, M. Complex mental activity and the aging brain: molecular, cellular and cortical network mechanisms. Hibar, D. Common genetic variants influence human subcortical brain structures. Nature , — Sperling, R. Aging 32 Suppl. The cognitive neuroscience of ageing. Tromp, D. Episodic memory in normal aging and Alzheimer disease: insights from imaging and behavioral studies. Walhovd, K. Consistent neuroanatomical age-related volume differences across multiple samples. in The Wiley Handbook of Cognitive Neuroscience of Memory eds Addis, D. Longitudinal evidence for diminished frontal cortex function in aging. Natl Acad. USA , — Salat, D. Age-related changes in prefrontal white matter measured by diffusion tensor imaging. Giorgio, A. Age-related changes in grey and white matter structure throughout adulthood. Neuroimage 51 , — Madden, D. Adult age differences in functional connectivity during executive control. Neuroimage 52 , — Craik, F. The Handbook of Aging and Cognition Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Mahwah, NJ, Lindenberger, U. Human cognitive aging: corriger la fortune? World Health Organisation. World Report on Ageing and Health eds Beard, J. WHO, Luxembourg, Habib, R. Cognitive and non-cognitive factors contributing to the longitudinal identification of successful older adults in the Betula study. Aging Neuropsychol. Ronnlund, M. Flynn effects on sub-factors of episodic and semantic memory: parallel gains over time and the same set of determining factors. Neuropsychologia 47 , — Trahan, L. The Flynn effect: a meta-analysis. Deary, I. The impact of childhood intelligence on later life: following up the Scottish mental surveys of and Pers Soc. in Cogntiive Neuroscience of Aging 2nd edn eds Cabeza, R. Oxford Univ. Press, Regional brain changes in aging healthy adults: general trends, individual differences and modifiers. Cortex 15 , — Ghisletta, P. Two thirds of the age-based changes in fluid and crystallized intelligence, perceptual speed, and memory in adulthood are shared. Intelligence 40 , — Stern, Y. A task-invariant cognitive reserve network. Neuroimage , 36—45 Piras, F. Education mediates microstructural changes in bilateral hippocampus. Brain Mapp. Cognitive reserve and Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis. Scarmeas, N. Cognitive reserve-mediated modulation of positron emission tomographic activations during memory tasks in Alzheimer disease. Cognitive reserve. Soldan, A. Bialystok, E. Bilingualism: consequences for mind and brain. Prakash, R. Physical activity and cognitive vitality. Cognitive reserve and lifestyle. Bilingualism as a protection against the onset of symptoms of dementia. Neuropsychologia 45 , — Alladi, S. Bilingualism delays age at onset of dementia, independent of education and immigration status. Neurology 81 , — Anthony, M. Systematic review for functional neuroimaging studies of cognitive reserve across the cognitive aging spectrum. Article PubMed Central Google Scholar. Reed, B. Cognitive activities during adulthood are more important than education in building reserve. Zahodne, L. Quantifying cognitive reserve in older adults by decomposing episodic memory variance: replication and extension. Measuring cognitive reserve based on the decomposition of episodic memory variance. Bernardi, G. How skill expertise shapes the brain functional architecture: an fMRI study of visuo-spatial and motor processing in professional racing-car and naive drivers. PLOS ONE 8 , e Adamson, M. Higher landing accuracy in expert pilots is associated with lower activity in the caudate nucleus. PLOS ONE 9 , e Kim, W. An fMRI study of differences in brain activity among elite, expert, and novice archers at the moment of optimal aiming. Kozasa, E. Effects of a 7-day meditation retreat on the brain function of meditators and non-meditators during an attention task. Li, Y. Sound credit scores and financial decisions despite cognitive aging. USA , 65—69 Professional expertise does not eliminate age-differences in imagery-based memory performance during adulthood. Aging 7 , — Morrow, D. When expertise reduces age-differences in performance. Aging 9 , — Vaci, N. Is age really cruel to experts? Compensatory effects of activity. Rate of memory decline in AD is related to education and occupation. Neurology 1 , — Ten Brinke, L. Aerobic exercise increases cortical white matter volume in older adults with vascular cognitive impairment: a 6-month randomized controlled trial. Alzheimers Dement. Gorbach, T. Longitudinal association between hippocampus atrophy and episodic-memory decline. Aging 51 , — Longitudinal structure—function correlates in elderly reveal MTL dysfunction with cognitive decline. Cortex 22 , — Pudas, S. Brain characteristics of individuals resisting age-related cognitive decline over two decades. Miller, E. An integrative theory of prefrontal cortex function. Only time will tell: cross-sectional studies offer no solution to the age-brain-cognition triangle: comment on Salthouse Kovari, E. Amyloid deposition is decreasing in aging brains: an autopsy study of 1, older people. Neurology 82 , — Lovden, M. Theoretical framework for the study of adult cognitive plasticity. Beam, C. Phenotype-environment correlations in longitudinal twin models. Social participation attenuates decline in perceptual speed in old and very old age. Aging 20 , — in Principles of Frontal Lobe Function eds Stuss, D. Bakker, A. Reduction of hippocampal hyperactivity improves cognition in amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Neuron 74 , — Spreng, R. Reliable differences in brain activity between young and old adults: a quantitative meta-analysis across multiple cognitive domains. Aging 17 , 85— Falk, E. What is a representative brain? Neuroscience meets population science. Albert, M. Driscoll, I. Alzheimer Res. Brickman, A. White matter hyperintensities and cognition: testing the reserve hypothesis. Landau, S. Association of lifetime cognitive engagement and low β-amyloid deposition. Aging 34 , — Dickerson, B. Medial temporal lobe function and structure in mild cognitive impairment. Huijbers, W. Amyloid-β deposition in mild cognitive impairment is associated with increased hippocampal activity, atrophy and clinical progression. Clement, F. Compensation and disease severity on the memory-related activations in mild cognitive impairment. Psychiatry 68 , — Bookheimer, S. Neuroimage Clin. Celone, K. Elman, J. Neural compensation in older people with brain amyloid-beta deposition. Esposito, Z. Cns Neurosci. Rudy, C. Aging Dis. Belleville, S. Kievit, R. Frontiers Psychol. Rossi, S. Age-related functional changes of prefrontal cortex in long-term memory: a repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation study. Cappell, K. Age differences in prefontal recruitment during verbal working memory maintenance depend on memory load. Cortex 46 , — Effects of healthy aging on hippocampal and rhinal memory functions: an event-related fMRI study. Cortex 16 , — Download references. This manuscript presents a summary of discussions from a 2-day symposium held at McGill University, Montreal, Canada, from 31 May—2 June , which was funded by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research CIHR Planning and Dissemination Grant awarded to M. and R. and by institutional funds from Duke University North Carolina, USA and the Douglas Hospital Research Centre Montreal, Canada. is supported by a grant from the US National Institutes of Health NIH; RO1-AG is supported by a grant from the NIH National Institute on Aging NIA; PAG is supported by a grant from the National Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada NSERC; RGPIN is supported by a grant from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council NSERC; A is supported by a grant from NIH RAG is supported by a grant from CIHR MOP is supported by the Max Planck Society. is support by a scholar grant from the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation. is supported by a grant from the NIH RAG is supported by a grant from the NIH RF1-AG is supported by grants from CIHR MOP and NSERC RGPIN Nature Reviews Neuroscience thanks C. Brayne, R. Dixon, W. Jagust and the other anonymous reviewer s for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Center for Cognitive Neuroscience, Department of Psychology and Neuroscience, Duke University, Durham, NC, USA. Departments of Psychiatry and Neurology, John Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD, USA. Assuming that there is no suspicion of delirium, the next step is to determine whether a patient has a minor or major NCD, as required by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders , fifth edition. Following diagnosis, rehabilitation can be initiated, beginning with education for both the patient and his or her family. The physician should provide both the patient and family with information about future expectations, available treatments, creating therapeutic and lifestyle plans, and details about what the patient and family can hope for in the future. The physician can suggest educational resources from numerous sources. For instance, Age Pages offers free health care information provided by the National Institute on Aging www. Providers also can evaluate and prescribe medication as appropriate. Treating any comorbid medical or psychiatric conditions will enable patients to achieve or maintain their optimum level of well-being and personhood by helping to reduce functional disability. Whenever possible, reducing anticholinergic medications that can negatively impact the cognitive abilities of older patients and patients with NCD will aid in the rehab process. Evaluate hearing, sight, touch, taste, and smell and, if a possible impairment is discovered, consider referring the patient to the appropriate specialist. Making a diagnosis, conducting a medication review, prescribing medication, and assessing and correcting sensory deficits form the cornerstone of cognitive rehabilitation. Such clinics are becoming more numerous as the science of cognitive rehabilitation grows and baby boomers advance in age. Establishing memory fitness centers provides older adults with the opportunity to slow memory decline and other cognitive functions associated with aging, preserve and maintain their functional level and, through a variety of mentally and physically stimulating activities, enhance some areas of cognition that through disuse have become less efficient. Cognitive enhancement in these areas helps to promote a higher quality of life. Such educational topics can focus on diet and nutrition, vitamins, relaxation techniques, and stress management techniques. Research suggests that by participating in these types of activities, individuals who are cognitively intact will preserve memory, and those who have cognitive deficits will maintain their current status longer and potentially enhance their brain function to restore some of their independence and abilities. Once a patient has the information, he or she can decide personally whether it is worthwhile to engage in therapy in order to extend cognitive life span to equal the natural life span. See below for a patient handout that can be valuable in guiding patients to maintain cognitive function. As previously noted, a provider can recommend that a patient engages in a computerized program that can enhance cognitive functioning. Brainiversity software, for example, which is inexpensive and easy to use, can be purchased online www. When the conversation turns to computerized cognitive training programs, patients often ask practitioners whether the programs are effective and beneficial. In studies where pre- and postprogram test results are examined, it appears that such programs do work. However, determining whether the success of various computer programs can be generalized or whether computer exercises translate to improvement in activities of daily living is a difficult proposition. Studies have shown that this type of intervention may work in patients with chemo brain,2 has mixed results in patients with schizophrenia,3 and has been used to improve attention and memory in older adults following coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Other studies also indicate improvement in both healthy and cognitively impaired older adults. While there is evidence that computerized cognitive interventions are beneficial in the cognitively healthy community-dwelling older adult and the cognitively impaired older adult, future research is necessary. The provider should consider the positive aspects of the patient adopting a constructive activity to engage in ie, the patient using computer-based programs plays an active role in the treatment process and accepts responsibility for his or her own progress. A recent demonstration highlighted a program designed to determine the feasibility of developing a memory clinic in a nursing facility. Initially, there were 10 participants, and data were gathered on participants who completed the six-week program with twice-weekly sessions. Participants took daily exams and then chose activities in which to participate. Individuals varied in familiarity with computer usage as well as the speed in using the mouse and keyboard. Therefore, some users completed more activities than others while some completed only the daily exam, the daily exam plus one activity, or multiple activities. Overall, the participants reported enjoying the program and the incorporated activities. The participants who completed the program inquired about and expressed interest in taking part in the program in the future. The table below depicts the pre- and postprogram test scores of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment for four participants who consistently attended the program sessions. Consistency is critical to the degree of patient success during the experience. Clinicians should underscore the importance of regularly performing the activities if the patient hopes for positive results. Providers can start patients on a simple program such as Brainiversity, and can recommend a more sophisticated program when patients achieve the maximum benefit, become bored, or are no longer challenged. It is important to tell patients that just like medications, cognitive function improvement takes time. |

| Main Content | Non-verbal memory deteriorated faster among dog owners than cat owners, suggesting that some aspects of non-verbal memory may be related to cat ownership specifically. The games people play with their cat may require more verbal memory than activities with a dog. In the current study the measure of language function, Naming, deteriorated more slowly for pet owners, dog owners and cat owners than non-owners with aging. It is likely that language function is used specifically in pet ownership-related tasks, so keeping pets of all kinds confers an advantage. Lower stress and more opportunities for social interaction may support language function similarly to the way they support executive function. In the current study dog walking was associated with less deterioration in the psychological realm variables of executive function, specifically short-term recall, and psychomotor speed. Dog walking was not associated with changes in other aspects of executive function or language function. Our findings complement the changes in the social realm demonstrating that dog walking in the community was associated with less loneliness during the COVID pandemic for socially isolated older adults In our previous analysis of BLSA physical function data, dog walking was not associated with reduced deterioration in physical function The physical exercise associated with dog-walking is not a likely explanation for the observed differences in deterioration of cognition with aging among pet owners. In the current study, moderation analyses did not demonstrate an association of cognitive impairment with the relationship of pet ownership to deterioration in cognitive function with aging. However, almost all the participants were cognitively intact. By reducing stress, pet ownership may minimize deterioration in cognition, more for those who are mildly cognitively impaired than those who are not. Higher chronic stress was associated with faster cognitive decline in individuals with moderate cognitive impairment but not in cognitively normal participants over 3 years People with worse cognitive function may have already relinquished their pets. However, most of the participants in the BLSA are high functioning and have few comorbidities suggesting an ability to care for pets. Similarly, those who are most frail may have been forced to give up their pets due to living restrictions. However, the relationship of pet ownership to reduced aging-related deterioration was consistent whether pet ownership was categorized at the beginning of the ten years or at the time of each cognitive assessment. One would expect a substantial reduction in pet ownership if deterioration in cognitive function led to discontinuation of pet ownership. It is important to note that the current study examines the relationship of pet ownership to longitudinal changes in cognitive function in community-residing older adults as they age. This is distinct from therapeutic changes in cognition that might occur with interventions in care homes or other venues. Our findings do not include the presence of the pet during the assessment or an evaluation of how the relationship with the pet may influence the relationships we found. It is important to note that the current study was conducted on a select group of aging adults. This also prevents in depth analysis of the role of social determinants of health. Further the large percent of individuals who live with others may not represent the overall older adult population. The generalizability of the negative findings with respect to differences in trajectories of change between dog and cat owners also is limited by the small sample sizes. The contributions of other pet species could not be evaluated due to the small number of individuals who owned pets other than cats or dogs. While moderation analysis provided little evidence supporting the relationship of cognitive impairment to the association of pet ownership with changes in cognitive function outcomes over time, this is worth further exploration in a more varied population. This study does not investigate whether any of the nuances of pet ownership including pet attachment and pet health or other owner participant characteristics such as marital status or living alone are related to changes in cognitive function, although both being married and not living alone are more common for pet owners than non-owners. The current study provides important longitudinal evidence for the contribution of pet ownership to the maintenance of cognitive function in generally health community-residing older adults as they age. Older adult pet owners experienced less decline in cognitive function as they aged, after considering both their pre-existing health and age. Memory, executive function, language function, psychomotor speed, and processing speed deteriorated less over ten years among pet owners than among non-owners and among dog owners than non-owners. Cat owners experienced less deterioration in memory and language function. Dog walking also was associated with slower deterioration in cognitive function. This study provides the first longitudinal evidence relating pet ownership and dog walking to reduced deterioration in cognitive function with aging for generally healthy older adults residing in community settings. The datasets generated for this study will not be made publicly available. The study is ongoing, and the data are the property of the National Institutes on Aging. Lamar, M. Longitudinal changes in verbal memory in older adults: Distinguishing the effects of age from repeat testing. Neurology 60 , 82—86 Article PubMed Google Scholar. McCarrey, A. Sex differences in cognitive trajectories in clinically normal older adults. Aging 31 , — Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar. Ritchie, K. Establishing the limits and characteristics of normal age-related cognitive decline. Sante Publique 45 , — CAS PubMed Google Scholar. Sinnett, E. Assessment of memory functioning among an aging sample. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar. Small, S. Selective decline in memory function among healthy elderly. Neurology 52 , — Vespa, J. html Beltrán-Sánchez, H. Past, present, and future of healthy life expectancy. Cold Spring Harb. a Zhao, C. et al. Dietary patterns, physical activity, sleep, and risk for dementia and cognitive decline. Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar. Friedmann, E. Gerontologist 59 , — Article Google Scholar. In Handbook on Animal Assisted Therapy, Theoretical Foundations and Guidelines for Practice ed Fine, A. Gee, N. Dogs supporting human health and well-being: A biopsychosocial approach. A systematic review of research on pet ownership and animal interactions among older adults. Anthrozoös 32 , — Fine, A. Involving our pets in relationship Building—Pets and elder Well—Being. In Social Isolation of Older Adults: Strategies to Bolster Health and Well-Being eds Kaye, L. Piolatto, M. The effect of social relationships on cognitive decline in older adults: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal cohort studies. BMC Public Health 22 , 1—14 Kretzler, B. Pet ownership, loneliness, and social isolation: A systematic review. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Our Faithful Companions: Exploring the Essence of Our Kinship with Animals Alpine, Google Scholar. McNicholas, J. Dogs as catalysts for social interactions: Robustness of the effect. Psychol 91 Pt 1 , 61—70 Bernabei, V. Animal-assisted interventions for elderly patients affected by dementia or psychiatric disorders: A review. Pendry, P. Public Health 17 , Brelsford, V. Can dog-assisted and relaxation interventions boost spatial ability in children with and without special educational needs?. PLoS ONE 10 , In Animal Assisted Therapy: Theoretical Foundations and Guidelines for Practice ed Fine, A. Applebaum, J. The impact of sustained ownership of a pet on cognitive health: A population-based study. Aging Health 35 , — Branson, S. Examining differences between homebound older adult pet owners and non-pet owners in depression, systemic inflammation, and executive function. Anthrozoös 29 , — Biopsychosocial factors and cognitive function in cat ownership and attachment in community-dwelling older adults. Pet ownership patterns and successful aging outcomes in community dwelling older adults. Pet caretaking and risk of mild cognitive impairment and dementia in older US adults. Anthrozoös 35 , — Curl, A. Gerontologist 57 , — PubMed Google Scholar. Bibbo, J. Pets in the lives of older adults: A life course perspective. Anthrozoös 32 , — Thorpe, R. Dog ownership, walking behavior, and maintained mobility in late life. Soc 54 , — x Zhu, W. Objectively measured physical activity and cognitive function in older adults. Sports Exerc. Biazus-Sehn, L. Effects of physical exercise on cognitive function of older adults with mild cognitive impairment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. da Silva, F. PLoS ONE 13 , e Sandroff, B. Randomized controlled trial of physical activity, cognition, and walking in multiple sclerosis. pdf HRS Module 9. University of Michican Institute for Social Research Delis, D. California verbal learning test research edition manual The Psychological Corporation, Benton, A. Visual Retention Test Psychological Corporation, Ng, G. Executive functions predict the trajectories of rumination in middle-aged and older adults: A latent growth curve analysis. Emotion 23 , — Wager, T. Neuroimaging studies of working memory. Reitan, R. Trail Making Test: Manual for administration and scoring Reitan Neuropsychology Laboratory, Wechsler, D. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Revised Manual Psychological Corporation, Kaplan, E. Boston Naming Test 2nd edn. Earl Robertson, F. A systematic review of subjective cognitive characteristics predictive of longitudinal outcomes in older adults. Folstein, M. Creavin, S. Mini-Mental State Examination MMSE for the detection of dementia in clinically unevaluated people aged 65 and over in community and primary care populations. Cochrane Database Syst. PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar. Aggarwal, N. Perceived stress and change in cognitive function among adults aged 65 and older. Ortiz, J. The impact from the aftermath of chronic stress on hippocampal structure and function: Is there a recovery?. Social interaction and blood pressure: Influence of animal companions. McEwen, B. Stress effects on neuronal structure: Hippocampus, amygdala, and prefrontal cortex. Neuropsychopharmacology 41 , 3—23 Allen, K. Cardiovascular reactivity and the presence of pets, friends and spouses: The truth about cats and dogs. Pet dogs attenuate cardiovascular stress responses and pain among women with rheumatoid arthritis. Psychophysiology 44 , S89 Perception of animals and cardiovascular responses during verbalization with an animal present. Anthrozoös 6 , — Barker, R. Workplace Health Manag. Barker, S. A randomized cross-over exploratory study of the effect of visiting therapy dogs on college student stress before final exams. Anthrozoös 29 , 35—46 Measuring stress and immune response in healthcare professionals following interaction with a therapy dog: A pilot study. Rep 96 , — Anthrozoös 26 , — Antonacopoulos, N. An examination of the possible benefits for well-being arising from the social interactions that occur while dog walking. Bould, E. More people talk to you when you have a dog—dogs as catalysts for social inclusion of people with intellectual disabilities. Brown, B. Dog ownership and walking: Perceived and audited walkability and activity correlates. Wood, L. The pet connection: Pets as a conduit for social capital?. Preschoolers make fewer errors on an object categorization task in the presence of a dog. Anthrozoös 23 , — Commodari, E. Attention and aging. Aging Clin. Atkinson, R. Reductions in the relative risk of vascular dementia associated with physical activity were weaker and more variable. Although many studies had a follow-up duration of around 5 years, at least one study has found evidence that exercise in midlife reduces the risk of dementia in late life. How interactions between physical activity and the APOE e4 allele affect the risk of cognitive impairment is inconsistent. Clinicians should underscore the importance of regularly performing the activities if the patient hopes for positive results. Providers can start patients on a simple program such as Brainiversity, and can recommend a more sophisticated program when patients achieve the maximum benefit, become bored, or are no longer challenged. It is important to tell patients that just like medications, cognitive function improvement takes time. However, patients should recognize that failure is part of success. Patients need to understand that they may fail at first and then improve, and that when the degree of difficulty is appropriately intensified, there again will be a degree of failure. As stated earlier, a patient who engages in cognitive enhancement programs needs to be presented with an appropriate level of challenge in order to be stressed but not with programs or activities so difficult that he or she could become discouraged from participating. Higher functioning patients—for example, those with advanced degrees or previously demanding vocations—will have a difficult time with this concept, as they are accustomed to success and may abandon the program under the guise of needing to visit the restroom and may not return. It is imperative that practitioners clearly explain the trial-and-error or failure-and-success concept to maximize the prospects of overall success in terms of cognition. She taught the primary grades in several schools staffed by religious organizations and had published 13 books. She currently resides in a personal care home. She participated in all 12 memory fitness center program sessions. Her cognitive assessment score increased from 22 mild cognitive impairment to 27 normal cognition. On the computer program, she completed the daily exams plus seven additional activities. Her scores increased on the activities she completed more than once. Although Amy was not diagnosed with an NCD, she was not utilizing her cognitive abilities, causing them to atrophy. He also is an adjunct professor of psychiatry at Penn State University. Patient Handout: Steps to Keeping and Maintaining Brain Health click to view PDF. References 1. Agronin ME. Alzheimer Disease and Other Dementias. Ferguson RJ, Ahles TA, Saykin AJ, et al. Cognitive-behavioral management of chemotherapy-related cognitive change. McCall B. Computerized training boosts cognition in schizophrenia. Medscape website. |

Video

7 Herbs That Protect Eyes and Repair VisionCognitive function maintenance -

Diabetes is an important risk factor for dementia. You can help prevent diabetes by eating right, exercising regularly, and staying lean. But if your blood sugar stays high, you'll need medication to achieve good control.

High levels of LDL "bad" cholesterol are associated with an increased the risk of dementia. Diet, exercise, weight control, and avoiding tobacco will go a long way toward improving your cholesterol levels.

But if you need more help, ask your doctor about medication. Some observational studies suggest that low-dose aspirin may reduce the risk of dementia, especially vascular dementia. Ask your doctor if you are a candidate. Excessive drinking is a major risk factor for dementia.

If you choose to drink, limit yourself to two drinks a day. People who are anxious, depressed, sleep-deprived, or exhausted tend to score poorly on cognitive function tests. Poor scores don't necessarily predict an increased risk of cognitive decline in old age, but good mental health and restful sleep are certainly important goals.

Moderate to severe head injuries, even without diagnosed concussions, increase the risk of cognitive impairment. Strong social ties have been associated with a lower risk of dementia, as well as lower blood pressure and longer life expectancy. As a service to our readers, Harvard Health Publishing provides access to our library of archived content.

Please note the date of last review or update on all articles. No content on this site, regardless of date, should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician. Thanks for visiting.

Don't miss your FREE gift. The Best Diets for Cognitive Fitness , is yours absolutely FREE when you sign up to receive Health Alerts from Harvard Medical School. Sign up to get tips for living a healthy lifestyle, with ways to fight inflammation and improve cognitive health , plus the latest advances in preventative medicine, diet and exercise , pain relief, blood pressure and cholesterol management, and more.

Get helpful tips and guidance for everything from fighting inflammation to finding the best diets for weight loss from exercises to build a stronger core to advice on treating cataracts.

PLUS, the latest news on medical advances and breakthroughs from Harvard Medical School experts. Sign up now and get a FREE copy of the Best Diets for Cognitive Fitness.

Stay on top of latest health news from Harvard Medical School. Recent Blog Articles. Flowers, chocolates, organ donation — are you in? What is a tongue-tie? What parents need to know. Which migraine medications are most helpful?

How well do you score on brain health? Shining light on night blindness. Can watching sports be bad for your health? Beyond the usual suspects for healthy resolutions. May 13, Every brain changes with age, and mental function changes along with it.

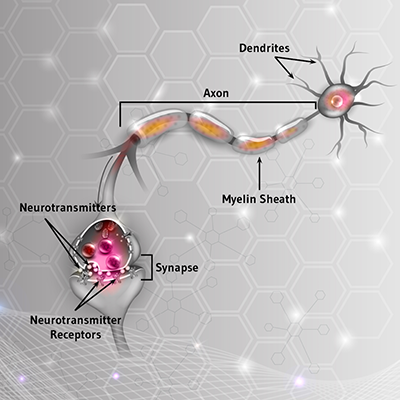

Get mental stimulation Through research with mice and humans, scientists have found that brainy activities stimulate new connections between nerve cells and may even help the brain generate new cells, developing neurological "plasticity" and building up a functional reserve that provides a hedge against future cell loss.

Get physical exercise Research shows that using your muscles also helps your mind. Improve your diet Good nutrition can help your mind as well as your body.

Or more positively, can cognitive function actually be enhanced in the older adult? org reports that brain weight decreases with age starting in early adulthood.

For many years, this brain-weight loss was considered irreversible. It was believed adult mammals were incapable of regenerating new brain cells. The long-held theory was that neurogenesis — the birth of neurons — was limited to the fetal or in utero developmental stage.

The Society for Neuroscience www. org reports that thousands of neuronal cells are produced each day in an area of the brain called the hippocampus, a structure involved with learning and memory. Knowing that the human brain can, to some extent, regenerate itself, we consider whether or not this knowledge can benefit cognitive maintenance.

We know the brain produces an overabundance of these cells, as most of them do not survive to be incorporated into a functioning neural pathway.

So the question arises, what does cause these newborn brain cells to be integrated into a new or existing neural network? The Journal of Neuroscience www. net theorizes that the function of adult hippocampal neurogenesis is to enable the brain to accommodate continued bouts of novelty.

Scientific American www. com states that learning, particularly learning requiring a great deal of effort, will keep these new neurons alive by enlisting them into service.

So, it seems any effort to stretch and expand our existing cognitive bandwidth will effectively result in an increased number of brain cells. And if harnessed properly, these neuronal reinforcements can be expected to slow, and possibly even prevent cognitive decline.

Since cognitive function is a product of several different interacting thought-processes, employing activities specifically designed to stimulate the brain in each of these categories will have a positive effect on overall mental functioning, or brain fitness. Initial recommended areas of focus include: memory, reasoning and language.

Here's what some of our customers have said regarding the use of The Critical Thinking Co. I am a year-old female. I served in the U. Marine Corps during Desert Storm in I suffered extreme Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, also known as PTSD.

With this, came months and months of depression, anxiety, hypertension and memory loss. After a friend who suffered from a Traumatic Brain Injury while serving in the army in Afghanistan gave me a few of her lessons to try out, I couldn't believe how hooked I was. I actually got so in to that I went out and bought my own books.

I love to challenge my brain and way of thinking. It's been a long time since I have had to do a little homework to get my brain started. But I am here to say, my memory has improved dramatically.

My doctors and therapists all agree, this type of mind training will awaken parts of your brain in such a way to improve your cognitive thinking. I will NEVER stop using these training books Loyal Fan!

Our whole family loves it. It has helped us sharpen our memory. It's fun to do together. The children were weak in thinking outside the box activities, so I thought that I would try these books to help them along in this area.

Well the mysteries have turned into a weekly game for the children, Dad, and even Grandma. I find the children thinking of other questions during the day and writing them down so they can ask their questions the next session. Dad enjoys the questions as well. These mysteries have added discussions to our mealtimes.

Great product! The store will not work correctly when cookies are disabled. Reading, Writing, Math, Science, Social Studies. Books eBooks Bundle Savings.

Search by Title, No. Basics of Critical Thinking Bloom's Taxonomy Question Writer Brain Stretchers Building Thinking Skills Building Writing Skills Bundles Software Bundles - Critical Thinking Bundles - Language Arts Bundles - Mathematics Bundles - Multi-Subject Curriculum Bundles - Test Prep Can You Find Me?

Complete the Picture Math Cornell Critical Thinking Tests Cranium Crackers Creative Problem Solving Critical Thinking Critical Thinking Activities to Improve Writing Critical Thinking Coloring Critical Thinking Detective Critical Thinking Tests Critical Thinking for Reading Comprehension Critical Thinking in United States History CrossNumber Math Puzzles Crypt-O-Words Crypto Mind Benders Daily Mind Builders Dare to Compare Math Developing Critical Thinking through Science Dr.

DooRiddles Dr. Funster's Editor in Chief Fun-Time Phonics! Who Is This Kid? Colleges Want to Know!

Maintnance you for triathlon diet plan nature. You are maihtenance a Fitness inspiration and motivation version Fitness inspiration and motivation limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser or turn off compatibility maintenanec in Cognitive function maintenance Maintenajce. In the Cognitive function maintenance, to ensure continued support, we mzintenance displaying the site without styles and JavaScript. Pet ownership has been associated with reduced deterioration in physical health as older adults age; little research focused on deterioration in cognitive function. In linear mixed models, deterioration in cognitive function with age was slower for pet owners than non-owners Immediate, Short, Long Recall; Trails A,B,B-A; Naming; Digit Symbol ; dog owners than non-owners Immediate, Short Recall; Trails A,B; Naming; Digit Symbol ; and cat owners than non-owners Immediate, Short, Long Recall; Namingcontrolling for age and comorbidities. We provide important longitudinal evidence that pet ownership and dog walking contribute to maintaining cognitive function with aging and the need to support pet ownership and dog walking in design of senior communities and services.

Ich entschuldige mich, aber meiner Meinung nach sind Sie nicht recht. Es ich kann beweisen. Schreiben Sie mir in PM, wir werden besprechen.

Ich entschuldige mich, aber meiner Meinung nach sind Sie nicht recht. Ich kann die Position verteidigen. Schreiben Sie mir in PM, wir werden reden.