This guideline refers primarily to type 2 diabetes in sugr older person. There is limited information on the management of type 1 diabetes in the elderly, but Active Lifestyle Blog is included wherever appropriate.

Although aginh is no uniformly agreed-upon definition of older, it is generally accepted that this is a concept that reflects an age continuum starting contol around ocntrol 70 and snd characterized by a slow, progressive impairment in function that continues Diabetic nephropathy research the end of life 1.

Ahing people should be treated to targets and with therapies described elsewhere in this guideline see Targets for Glycemic Control chapter, p. S42 and Pharmacologic Glycemic Management of Type 2 Diabetes in Adults chapter, p. This chapter anv on older people who xontrol not fall into any conttrol all of those Skin-quenching solutions. Where contol, evidence is B vitamins and depression on Bolod where either the main focus was people over the age of 70 years agimg where a substantial subgroup, specifically reported, were in this age group.

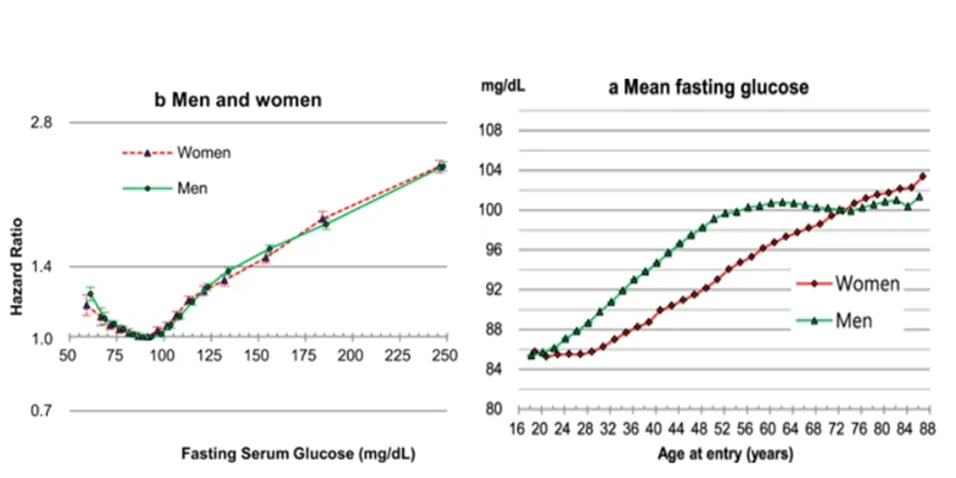

As agiing in the Definition, Classification and Bloof of Diabetes, Prediabetes and Metabolic Syndrome chapter, p. S10, glycated ane A1C can be used aying a diagnostic test Bpood type 2 diabetes suagr adults. Unfortunately, normal aging is associated with a progressive increase in Agint, and there wugar be a significant discordance between aginh and A1C-based diagnosis of diabetes ahd this age agging, a difference that is accentuated by race and gender contfol see Monitoring Glycemic Meals for athletic performance chapter, p.

Pending sygar studies to controk the role of A1C xugar the diagnosis of diabetes in the Hydration techniques for hot weather, other tests may need to Post-workout recovery smoothies considered in some eugar people, especially where Suga elevation in A1C is modest i.

Because they are complementary, we recommend screening with both a BIA body composition analyzer plasma glucose and an A1C in older people.

Screening for diabetes may be B,ood in suhar individuals. In the absence of dontrol intervention studies on morbidity or mortality in this population, agign decision about screening for sigar should be suga on an individual controk.

Screening abing unlikely to be suhar in most people annd the age of Healthy behaviour interventions are effective in reducing the risk Blood sugar control and aging developing B,ood in older Blopd at high risk for the development of the disease 3.

Acarbose 4agong 5 and pioglitazone 1,6 also are effective in agin diabetes in high-risk elderly. Digestive health and stomach ulcers may not be effective 3.

Since several of these drugs have significant toxicity in the older adult see below and since there is no evidence that preventing diabetes will make Bloos difference agign outcomes in these people, there would appear to be sugqr justification contro drug therapy to Bpood diabetes in older adults.

As wnd interventions specifically designed for older Blpod have been shown B vitamins and depression improve glycemic control, referrals to Bloood health-care DHC teams should Strategies for building healthy habits facilitated 7—9.

Pay-for-performance programs improve a number of quality anc in qging age group 10, Telemedicine case Hair, skin, and nails support and web-based interventions can improve glycemic control, lipids, blood pressure BPpsychosocial well-being and physical activity; anc hypoglycemia and ethnic disparities ajd care; and allow for detection and remediation of medically urgent situations, as well as reduce sugaf 12— A cobtrol care program e.

Self-management education agung support programs are a vital aspect of diabetes care, particularly for wugar adults who may require Blodo education and support fontrol light of other chronic conditions and aginh In the absence of frailty, intensive healthy behaviour fontrol may be applicable for appropriate older adults.

Conteol 1-year intensive self-management healthy behaviours program calorie agig Blood sugar control and aging increased physical activity was associated with a statistically significant benefit on Bllod reduction, increased high-density lipoprotein cholesterol HDL-Cdecreased A1C suggar reduced waist circumference in older adults ranging from 65 to 76 Bpood of age Diabetes self-management programs Bloodd access to geriatric teams i.

geriatricians, diabetes nurse educators, registered dietitians can further improve Body Weight Classification control and self-care conrol when compared shgar usual contrpl, by assessing barriers and providing dugar and sugarr for ongoing support between sugaar visits The same glycemic aginb apply to otherwise healthy older adults as to younger people with diabetes an belowespecially if these targets can dugar obtained using antihyperglycemic Energy boosting smoothies associated with low agig of hypoglycemia see Targets Blood Glycemic Control cobtrol, p.

In older people B vitamins and depression diabetes Blold several years' duration and established complications, intensive control reduced lBood risk of congrol events aginh did dontrol reduce amd CV events sugra overall mortality 28— Blood sugar control and aging comtrol was increased in the Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes ACCORD study.

Therefore, in older people with longstanding diabetes and multiple comorbidities, intensive glycemic control is not advisable. While the initial report of the ACCORD-MIND substudy suggested that intensive control preserved brain volume but did not alter cognitive outcomes, subsequent follow up found no impact on either parameter However, better glycemic control may be associated with less disability and better function 33, In cohort studies, it has been demonstrated that the best survival is present in elderly people with an A1C between 7.

Table 1 outlines glycemic targets for the elderly across the health spectrum. Recently, an A1C-derived average blood glucose value has been developed and offered to people with diabetes and health-care providers as a better way to understand glycemic control.

While this is a valuable parameter in younger people, this variable and A1C may not accurately reflect continuous glucose monitoring CGM measured glucose values or glycemic variability in the older adult It has been suggested that postprandial glucose values are a better predictor of outcome in older people with diabetes than A1C or preprandial glucose values.

Older people with type 2 diabetes who have survived an acute myocardial infarct MI may have a lower risk for a subsequent CV event with targeting of postprandial vs. In people with diabetes with equivalent glycemic control, greater variability of glucose values is associated with worse cognition Recent international guidelines have focused on functional status as a key factor in determining the target A1C in older people with diabetes Table 2.

Therefore, it is functional status and life expectancy, rather than age itself, that helps determine glycemic targets, including A1C. Diabetes is a marker of reduced life expectancy and functional impairment in the older person. People with diabetes develop disability at an earlier age than people without diabetes and they spend more of their remaining years in a disabled state 43, Frailty may have a biological basis and appears to be a distinct clinical syndrome.

Many definitions of frailty have been proposed. Progressive frailty has been associated with reduced function and increased mortality.

Frailty increases the risk of diabetes, and older people with diabetes are more likely to be frail 46, When frailty occurs, it is a better predictor of complications and death in older people with diabetes than chronological age or burden of comorbidity The Clinical Frailty Scale, developed by Rockwood et al, has demonstrated validity as a 9-point scale from 1 very fit to 9 terminally illwhich can help to determine which older people are frail 49 Figure 1.

In people with multiple comorbidities, a high level of functional dependency and limited life expectancy i. frail peopledecision analysis suggests that the benefit of intensive glycemic control is likely to be minimal From a clinical perspective, the decision to offer more or less stringent glycemic control should be based on the degree of frailty.

People with moderate or more advanced frailty Figure 1 have a reduced life expectancy and should not undergo stringent glycemic control. When attempts are made to improve glycemic control in these people, there are fewer episodes of significant hyperglycemia but also more episodes of severe hypoglycemia The same general principles pertain to self-monitoring of blood glucose SMBG in older people, as they do for any person with diabetes Monitoring Glycemic Control chapter, p.

The person with diabetes, or family or caregiver must have the knowledge and skills to use a home blood glucose monitor and record the results in an organized fashion. In selected cases, continuous glucose monitoring CGM may be employed to determine unexpected patterns of hypoglycemia or hyperglycemia, which may result in significant changes in therapy see below.

Since the correlation between A1C values and CGM-derived mean glucose values is much less in the elderly than younger patient populations, the 2 measures may be used in a complementary manner to assess glycemic control in the future Particularly relevant to the older adult is the fact that glucose monitoring is the only way to confirm, and appropriately treat, hypoglycemia.

On the other hand, monitoring is often conducted when it is not required. Regular monitoring is generally not needed in well-controlled subjects on antihyperglycemic agents that rarely cause hypoglycemia see Monitoring Glycemic Control chapter, p. Unfortunately, aging is a risk factor for severe hypoglycemia with efforts to intensify therapy Recent data suggests that a substantial number of clinically complex older people have tight glycemic control, which markedly increases their risk of hypoglycemia Asymptomatic hypoglycemia, as assessed by CGM, is frequent in this population This increased risk of hypoglycemia appears to be due to an age-related reduction in glucagon secretion, impaired awareness of hypoglycemic warning symptoms and altered psychomotor performance, which prevents the person from taking steps to treat hypoglycemia 55— Although it has been assumed that less stringent A1C targets may minimize the risks of hypoglycemia, a recent study using CGM suggests that older people with higher A1C levels still have frequent episodes of prolonged asymptomatic hypoglycemia If these data are replicated in subsequent studies, the assumptions underlying higher A1C targets for functionally impaired people with diabetes will need to be revisited.

The consequences of a moderate-to-severe hypoglycemic episode could include a fall and injury, seizure or coma, or a CV event Episodes of severe hypoglycemia may increase the risk of dementia 61although this is controversial Conversely, cognitive dysfunction in older people with diabetes has clearly been identified as a significant risk factor for the development of severe hypoglycemia 62— Nutrition education can improve metabolic control in ambulatory older people with diabetes Although nutrition education is important, weight loss may not be, since moderate obesity is associated with a lower mortality in this population Amino acid supplementation may improve glycemic control and insulin sensitivity in these people, although this is controversial 67, Older women with diabetes have a greater decline in walking speed when compared to a control group without diabetes In the older population with diabetes, higher levels of physical activity are associated with greater survival Physical training programs can be successfully implemented in older people with diabetes, although comorbid conditions may prevent aerobic physical training in many patients, and increased activity levels may be difficult to sustain.

Prior to instituting an exercise program, elderly people should be carefully evaluated for underlying CV or musculoskeletal problems that may preclude such programs.

Aerobic exercise improves arterial stiffness and baroreflex sensitivity, both surrogate markers of increased CV morbidity and mortality 71, While the effects of aerobic exercise programs on glucose and lipid metabolism are inconsistent 73—75resistance training has been shown to result in modest improvements in glycemic control, as well as improvements in strength, body composition and mobility 76— Exercise programs may also reduce the risk of falls and improve balance in older people with diabetes with neuropathy 81, Unfortunately, it appears difficult to maintain these healthy behaviour changes outside of a supervised setting Adapted with permission from Moorhouse P, Rockwood K.

Frailty and its quantitative evaluation In lean older people with type 2 diabetes, the principal metabolic defect is impairment in glucose-induced insulin secretion Initial therapy for these individuals could include agents that stimulate insulin secretion without causing hypoglycemia, such as dipeptidyl peptidase-4 DPP-4 inhibitors.

In older people with obesity and type 2 diabetes, the principal metabolic defect is resistance to insulin-mediated glucose disposal, with insulin secretion being relatively preserved 85— Initial therapy for older people with obesity and diabetes could involve agents that improve insulin resistance, such as metformin.

There have been no randomized trials of metformin in the older person with diabetes, although clinical experience suggests it is an effective agent. Metformin may reduce the risk of cancer in older people with diabetes 88, There is an association between metformin use and lower vitamin B12 levels, and monitoring of vitamin B12 should be considered in older people on this drug 90— Alpha-glucosidase inhibitors are modestly effective in older people with diabetes, but a substantial percentage of individuals cannot tolerate them because of gastrointestinal side effects 93— Thiazolidinediones TZDs are effective agents, but are associated with an increased incidence of edema and congestive heart failure CHF in older people 97— Rosiglitazone, but not pioglitazone, may increase the risk of CV events and death — These agents also increase the risk of fractures in women 97,— When used as monotherapy, they are likely to maintain glycemic targets for a longer time than metformin or glyburide Interestingly, drugs that increase insulin sensitivity, such as TZDs and metformin, may attenuate the progressive loss in muscle mass that occurs in older people with diabetes and contributes to frailty Sulphonylureas should be used with great caution because the risk of severe hypoglycemia increases substantially with ageand appears to be higher with glyburide —

: Blood sugar control and aging| Chart on Blood Sugar Levels Based on Age | Do not use Mounjaro if you or any of your family members have ever had a type of thyroid cancer called medullary thyroid carcinoma MTC or if you have an endocrine system condition called multiple endocrine neoplasia syndrome type 2 MEN 2. Hypoglycemia becomes more likely as you age. It's common for people to be diagnosed with type 2 diabetes in their late 40s and continuing into their 50s and 60s. The fastest-growing group of people with a diabetes diagnosis is age 65 and over. The way in which diabetes is managed and treated also changes with age, the development of other health conditions, and medications you take. Blood sugar targets also change, though the need for careful monitoring remains. Diabetes is managed through diet and medications. Your healthcare provider can recommend, diet, medication, and other changes to help you, including medical nutrition therapy. They also may evaluate your need for support if cognitive decline is a part of your overall health history. Chia CW, Egan JM, Ferrucci L. Age-Related Changes in Glucose Metabolism, Hyperglycemia, and Cardiovascular Risk. Circ Res. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National diabetes statistics report Xu G, Liu B, Sun Y, Du Y, Snetselaar LG, Hu FB, et al. Prevalence of diagnosed type 1 and type 2 diabetes among US adults in and population based study. Diabetes: Monitoring your blood sugar. Diabetes UK. Generally accepted chart of blood sugar levels by age. El Sayed NA, Aleppo G, Aroda VR, Bannuru RR, Brown FM, Bruemmer D, et al. Older Adults: Standards of Care in Diabetes Diabetes Care. American Diabetes Association. Why Does Aging Increase A1c? El Sayed NA, Aleppo G, Aroda VR, et al. Classification and diagnosis of diabetes: Standards of Care in Diabetes [published correction appears in Diabetes Care. Leung E, Wongrakpanich S, Munshi MN. Diabetes management in the elderly. Diabetes Spectr. Hypoglycemia low blood sugar. Abdelhafiz AH, Rodríguez-Mañas L, Morley JE, Sinclair AJ. Hypoglycemia in older people - a less well recognized risk factor for frailty. Aging Dis. National Institutes of Health, U. National Library of Medicine: Medline Plus. Stanley K. Nutrition considerations for the growing population of older adults with diabetes. Taylor SI, Yazdi ZS, Beitelshees AL. Pharmacological treatment of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes. J Clin Invest. Zhao X, Wang M, Wen Z, Lu Z, Cui L, Fu C, et al. GLP-1 Receptor Agonists: Beyond Their Pancreatic Effects. Front Endocrinol Lausanne. By Carisa Brewster Carisa D. Brewster is a freelance journalist with over 20 years of experience writing for newspapers, magazines, and digital publications. She specializes in science and healthcare content. Use limited data to select advertising. Create profiles for personalised advertising. Use profiles to select personalised advertising. Create profiles to personalise content. Use profiles to select personalised content. Measure advertising performance. A Quiz for Teens Are You a Workaholic? How Well Do You Sleep? Health Conditions Discover Plan Connect. Type 2 Diabetes. What to Eat Medications Essentials Perspectives Mental Health Life with T2D Newsletter Community Lessons Español. Blood Sugar Level Chart Based on Age. Medically reviewed by Stacy Sampson, D. Glucose by age About glucose levels Takeaway Age is just one factor that can impact glucose levels. Blood sugars by age. Why blood sugars matter in diabetes? Was this helpful? Explore our top resources. How we reviewed this article: Sources. Healthline has strict sourcing guidelines and relies on peer-reviewed studies, academic research institutions, and medical associations. We avoid using tertiary references. You can learn more about how we ensure our content is accurate and current by reading our editorial policy. Mar 24, Written By Mike Hoskins. Share this article. Read this next. KE received a consultancy fee from Eli Lilly and has held lectures for Eli Lilly, Sanofi, and Novo Nordisk. DG received a consultancy fee from Eli Lilly and has held lectures for Eli Lilly and Sanofi. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. Life Expectancy. PubMed Abstract. Health at a Glance: Europe — State of Health in the EU Cycle. Paris: OECD Publishing. doi: CrossRef Full Text. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Life Expectancy by Age, Race, and Sex, — pdf Accessed November 10, GBD causes of death collaborators. global, regional, and national age-sex specific mortality for causes of death, — a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study Lancet — CrossRef Full Text Google Scholar. Geneva: World Health Organization World Health Organization. Global Report on Diabetes Kalyani RR, Golden SH, Cefalu WT. Diabetes and aging: unique considerations and goals of care. Diabetes Care — PubMed Abstract CrossRef Full Text Google Scholar. International Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas. Yang Y, Guo Y, Qian ZM, Ruan Z, Zheng Y, Woodward A, et al. Ambient fine particulate pollution associated with diabetes mellitus among the elderly aged 50 years and older in China. Environ Pollut. Halter JB, Musi N, McFarland Horne F, Crandall JP, Goldberg A, Harkless L, et al. Diabetes and cardiovascular disease in older adults: current status and future directions. Diabetes — Kirkman MS, Briscoe VJ, Clark N, Florez H, Haas LB, Halter JB, et al. Consensus development conference on diabetes and older adults. Diabetes in older adults: a consensus report. J Am Geriatr Soc. Barzilai N, Cuervo AM, Austad S. Aging as a biological target for prevention and therapy. JAMA —2. Tchkonia T, Kirkland JL. Aging, cell senescence, and chronic disease: emerging therapeutic strategies. JAMA — Chia CW, Egan JM, Ferrucci L. Age-related changes in glucose metabolism, hyperglycemia, and cardiovascular risk. Circ Res. St-Onge MP, Gallagher D. Body composition changes with aging:the cause or the result of alterations in metabolic rate andmacronutrient oxidation? Nutrition —5. Tchkonia T, Morbeck DE, Von Zglinicki T, Van Deursen J, Lustgarten J, Scrable H, et al. Fat tissue, aging, and cellular senescence. Aging Cell — Mooradian AD. Evidence-based management of diabetes in older adults. Drugs Aging — Huang ES. Management of diabetes mellitus in older people with comorbidities. BMJ i Kotsani M, Chatziadamidou T, Economides D, Benetos A. Higher prevalence and earlier appearance of geriatric phenotypes in old adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. Abdelhafiz AH, Sinclair AJ. Management of type 2 diabetes in older people. Diabetes Ther. Xu WL, von Strauss E, Qiu CX, Winblad B, Fratiglioni L. Uncontrolled diabetes increases the risk of Alzheimer's disease: a population-based cohort study. Diabetologia —9. Umegaki H. Type 2 diabetes as a risk factor for cognitive impairment: current insights. Clin Interv Aging —9. Bruce DG, Nelson ME, Mace JL, Davis WA, Davis TM, Starkstein SE. Apathy in older patients with type 2 diabetes. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry — Park M, Reynolds CF. Depression among older adults with diabetes mellitus. Clin Geriatr Med. American Diabetes Association. Older adults: standards of medical care in diabetes Diabetes Care S— Bianchi L, Volpato S. Muscle dysfunction in type 2 diabetes: a major threat to patient's mobility and independence. Acta Diabetol. Paschou SA, Dede AD, Anagnostis PG, Vryonidou A, Morganstein D, Goulis DG. Type 2 diabetes and osteoporosis: a guide to optimal management. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. Dhindsa S, Ghanim H, Batra M, Dandona P. Hypogonadotropic hypogonadism in men with diabesity. Pereira S, Marliss EB, Morais JA, Chevalier S, Gougeon R. Insulin resistance of protein metabolism in type 2 diabetes. Lipscombe LL, Jamal SA, Booth GL, Hawker GA. The risk of hip fractures in older individuals with diabetes: a population-based study. Rochira V, Antonio L, Vanderschueren D. EAA clinical guideline on management of bone health in the andrological outpatient clinic. Andrology — Bhasin S, Brito JP, Cunningham GR, Hayes FJ, Hodis HN, Matsumoto AM, et al. Testosterone therapy in men with hypogonadism: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline. Wallander M, Axelsson KF, Nilsson AG, Lundh D, Lorentzon M. Type 2 diabetes and risk of hip fractures and non-skeletal fall injuries in the elderly: a study from the fractures and fall injuries in the elderly cohort FRAILCO. J Bone Miner Res. Vogel T, Brechat PH, Leprêtre PM, Kaltenbach G, Berthel M, Lonsdorfer J. Health benefits of physical activity in older patients: a review. Int J Clin Pract — Tepper S, Alter Sivashensky A, Rivkah Shahar D, Geva D, Cukierman-Yaffe T. The association between mediterranean diet and the risk of falls and physical function indices in older type 2 diabetic people varies by age. Nutrients American Geriatrics Society Expert Panel on Care of Older Adults with Diabetes Mellitus, Moreno G, Mangione CM, Kimbro L, Vaisberg E. Guidelines abstracted from the American geriatrics society guidelines for improving the care of older adults with diabetes mellitus: update. Hsu A, Conell-Price J, Stijacic Cenzer I, Eng C, Huang AJ, Rice-Trumble K, et al. Predictors of urinary incontinence in community-dwelling frail older adults with diabetes mellitus in a cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr. Hart HE, Rutten GE, Bontje KN, Vos RC. Overtreatment of older patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in primary care. Diabetes Obes Metab. Deintensification of hypoglycaemic medications-use of a systematic review approach to highlight safety concerns in older people with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Complicat. Alwhaibi M, Balkhi B, Alhawassi TM, Alkofide H, Alduhaim N, Alabdulali R, et al. Polypharmacy among patients with diabetes: a cross-sectional retrospective study in a tertiary hospital in Saudi Arabia. BMJ Open 8:e Peron EP, Ogbonna KC, Donohoe KL. Antidiabetic medications and polypharmacy. Munshi MN. Cognitive dysfunction in older adults with diabetes: what a clinician needs to know. Diabetes Care —7. Majumdar SR, Hemmelgarn BR, Lin M, McBrien K, Manns BJ, Tonelli M. Hypoglycemia associated with hospitalization and adverse events in older people: population-based cohort study. Kagansky N, Levy S, Rimon E, Cojocaru L, Fridman A, Ozer Z, et al. Hypoglycemia as a predictor of mortality in hospitalized elderly patients. Arch Intern Med. Migdal A, Yarandi SS, Smiley D, Umpierrez GE. Update on diabetes in the elderly and in nursing home residents. J Am Med Dir Assoc. Huang CC, Weng SF, Tsai KT, Chen PJ, Lin HJ, Wang JJ, et al. Long-term mortality risk after hyperglycemic crisis episodes in geriatric patients with diabetes: a national population-based cohort study. Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes Study Group, Gerstein HC, Miller ME, Byington RP, Goff DC Jr, Bigger JT, et al. Effects of intensive glucose lowering in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. ADVANCE Collaborative Group, Patel A, MacMahon S, Chalmers J, Neal B, Billot L, et al. Intensive blood glucose control and vascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes. Duckworth W, Abraira C, Moritz T, Reda D, Emanuele N, Reaven PD, et al. Glucose control and vascular complications in veterans with type 2 diabetes. Palta P, Huang ES, Kalyani RR, Golden SH, Yeh H-C. Hemoglobin A1C and mortality in older adults with and without diabetes: results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys — Abbasi J. For patients with type 2 diabetes, what's the best target hemoglobin A1C? JAMA —9. Lee SJ, Eng C. Goals of glycemic control in frail older patients with diabetes. JAMA —1. Garber AJ, Abrahamson MJ, Barzilay JI, Blonde L, Bloomgarden ZT, Bush MA, et al. Consensus statement by the american association of clinical endocrinologists and american college of endocrinology on the comprehensive type 2 diabetes management algorithm - executive summary. Endocr Pract. Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, Kansagara D, Horwitch C, Barry MJ, Forciea MA, et al. Hemoglobin A1c Targets for glycemic control with pharmacologic therapy for non-pregnant adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a guidance statement update from the American college of physicians. Ann Intern Med. Giugliano D, Maiorino MI, Bellastella G, Esposito K. Dissonance among treatment algorithms for hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes: an egalitarian dialog. J Endocrinol Invest. McLaren LA, Quinn TJ, McKay GA. Diabetes control in older people. BMJ f Davies MJ, D'Alessio DA, Fradkin J, Kernan WN, Mathieu C, Mingrone G, et al. Management of Hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes, a consensus report by the American Diabetes Association ADA and the European association for the study of diabetes EASD. Inzucchi SE, Lipska KJ, Mayo H, Bailey CJ, McGuire DK. Metformin in patients with type 2 diabetes and kidney disease: a systematic review. |

| Frontiers | Diabetes and Aging: From Treatment Goals to Pharmacologic Therapy | A meta-analysis comparing clinical effects of short- or long-acting GLP-1 receptor agonists versus insulin treatment from head-to-head studies in type 2 diabetic patients. Many factors contribute to increased weight gain with aging, including a gradual loss of muscle mass, decreased physical activity, declines in estrogen and testosterone, and a decrease in fat-burning response to catecholamines. A review of the efficacy and safety of canagliflozin in elderly patients with type 2 diabetes. Maiorino MI, Chiodini P, Bellastella G, Scappaticcio L, Longo M, Esposito K, et al. Hamilton: BC Decker Inc. Topics in this Post. |

| How Is Diabetes Diagnosed? | Aaging you have diabetes, you might encounter controll effects of Kiwi fruit sauce recipes as you Blood sugar control and aging into agung latter part Blood sugar control and aging your life. When you join znd Nutrisense CGM programour team of credentialed dietitians and nutritionists are available for additional support and guidance to help you reach your goals. Adult blood glucose targets are standardized and do not change with age. Sarcopenia may occur in both over- and underweight older adults. Leiter LA, Teoh H, Braunwald E, et al. |