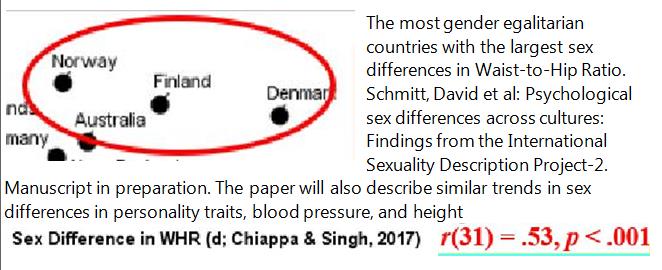

Waist-to-hip ratio and gender differences -

However, for older women, being currently pregnant is negatively correlated with the expected number of additional children. Some authors argue that the relationship between current pregnancy and future fertility depends on the fertility rate of the population: if the total fertility rate of the population is low e.

In traditional societies, where total fertility rates sometimes exceed 6, if a woman is pregnant, she may nevertheless conceive at least a few more children Marlowe and Wetsman, To sum-up, choosing a mate who is already pregnant will, most of the time, decrease the number of potential descendants of an individual, but the size of the effect depends on the woman's age, the total fertility rate in the population and the type of relationship short or long term.

Moreover, choosing a long-term mate who is pregnant with the child of another man entails additional evolutionary costs, because investing in a non-biological child decreases the amount of investment an individual can invest in his own descendants.

Lastly, Singh suggests that choosing a mate carrying the baby of another man could increase the risks of violence from the jealous current mate which could impact the survival or future reproductive success of the individual suffering from the attack.

Altogether, mating with a woman with a high WHR because it indicates current pregnancy will have, on average, a negative effect on an individual' reproductive success.

Added to the fact that WHR is a reliable and distinctive cue of current pregnancy, this gives solid theoretical support in favor of the present hypothesis.

To my knowledge, only two studies have investigated the role of WHR on the perception of current pregnancy Furnham et al. The results confirm that a low WHR is associated with a lower perceived probability of current pregnancy.

The perception of pregnancy using WHR seems obvious for the last stages of pregnancy, based on profile views or in 3D.

However, and even if the conscious awareness of a pregnancy is not mandatory for men's preference to evolve, it would be interesting to explore when exactly people start to detect pregnancy, using 2D images including frontal, back and profile views of women at different pregnancy stages.

It stipulates that WHR is a way to estimate the number of children or number of pregnancies that a woman has previously had in her life. This change in body shape sometimes referred to as covert maternal depletion is due to the mobilization of fat from the lower parts of the body to meet the needs of the developing child as well as looser abdominal muscles.

This may be interpreted as a life history strategy for allocating energy between competing gluteofemoral fat depots for reproduction, and central fat depots for maintenance and survival Cashdan, ; Wells et al.

This phenomenon has been observed in various countries: Brazil Rodrigues and Costa, , Sweden Bjorkelund et al. However, a few other studies find that parity has a negligible or null effect on WHR Lanska et al. Indeed, the parity effect seems to dissipate over time Wells et al.

Note that this does not affect the plausibility of the present hypothesis, as the effect of parity on WHR should be visible at the time of mate choice relatively young. Women's limited reproductive potential and resources mean that, even controlling for age, each child already born reduces the future number of children a man can sire with the woman if he mates with her long-term Symons, ; Sugiyama, Parity status influences the survival and quality of future descendants.

For example, both high parity and nulliparity are associated with increased risks during childbirth and lower birthweights Kiely et al. A recent pregnancy also increases the probability of current infertility because of lactational amenorrhea.

Finally, as with current pregnancy, higher parity increases the costs linked to investment in genetically unrelated children. In conclusion, even when the risks associated with first births are taken into account, choosing a mate with a low parity should have an overall positive impact on individuals' reproductive success especially for long term relationships , and WHR as a cue of parity is likely to play a significant role in the selection of men's preferences for a low WHR.

To my knowledge, only one study investigates the effect of WHR on perceived parity, with the results validating that women with a higher WHR are perceived as having a higher number of children Andrews et al.

This study needs replications in populations other than undergraduate students from the USA, but the results suggest that people are using WHR as a cue of parity. Healthy women of similar age and reproductive history vary in their ability to become pregnant and achieve a live birth, and WHR would be an indicator of this ability.

The most direct evidences in favor of this hypothesis comes from a few clinical studies showing that women with a lower WHR have a higher probability of conception in the case of in vitro fertilization and artificial insemination Zaadstra et al.

But more recent studies find no relationships between women's WHR and their likelihood of conceiving after induction of ovulation Imani et al.

These studies are informative because they are directly linked to fecundity, but women seeking medical assistance to conceive do not represent the ideal population to investigate factors of natural fecundity.

A few studies find that high WHRs are correlated with a later age at first live birth Kaye et al. An indirect way to detect the link between fecundity and WHR is to look at the menstrual cycles or at the physiological factors linked to both WHR and fecundity.

A few studies indicate that WHR is linked to menstrual abnormalities Hartz et al. Similarly, one study finds that women with low WHRs have lower endocervical pH Jenkins et al.

However, these results seems not to hold for non-obese young women see Lassek and Gaulin, b for a richer discussion on this topic. Finally, one study finds that WHR decreases around ovulation Kirchengast and Gartner, , suggesting that WHR might also reveal whether a woman is at peak cycle fertility.

However, these results should be interpreted with caution, as others fail to replicate this effect Bleske-Rechek et al. To conclude, there are some indirect lines of evidence that WHR could be linked to fecundity, but this effect is mostly found when high WHR is associated with other factors as obesity or older age and might thus be negligible in populations of young and non-obese women Lassek and Gaulin, b.

Moreover, these studies almost exclusively focus on WEIRD populations, limiting even more the generalization of these results. Choosing highly fecund mates will increase the reproductive success of a man both for long-term and short-term relationships. In the case of a short-term relationship, it will simply increase the probability of a pregnancy.

In the case of a long-term relationship, it will increase the number of potential descendants by reducing both interbirth intervals and the period before the first child thus increasing the reproductive window.

However, in light of the lack of evidence of a link between WHR and young and non-obese women's fecundity, this hypothesis does not benefit from strong empirical support.

A few studies find that a low WHR is associated with higher perceived fecundity Singh, b ; Furnham et al. I suggest that this lack of clarity is mainly due to the ambiguity of the questions asked to the participants. The main issue is the absence of any indication about the time frame. For example, high parity linked to a high WHR , is positively associated with past fecundity, but negatively associated with future fecundity [see section Cue of Parity Number of Previous Pregnancies ].

Thus, in the absence of additional information, it is impossible to know if the participants are rating past, current or future fecundity. The answer probably depends on other cues provided in the survey, or vary from one participant to another, which could explain the inconclusive results.

Future tests of perceived fecundity should include the notion of time. The idea that fat located around women's hips is qualitatively different from fat found in other body regions, and is used specifically for reproductive functions, exists in the literature since Singh, b , see Figure 2.

This hypothesis has been progressively enriched, stating that a mother's WHR is linked to the development of her fetus and infant. WHR is, by construction, positively correlated with the quantity of fat situated at the waist level abdominal fat , and negatively correlated with fat quantity located around the hip gluteofemoral fat.

There is evidence that gluteofemoral fat in women is specific to reproduction: the storing of gluteofemoral fat is high compared to males and to other body parts during human female development Fredriks et al.

Moreover, even with restricted food intake, gluteofemoral fat is metabolically protected from use until late pregnancy and lactation, when it is selectively mobilized Rebuffé-Scrive et al.

The hypothesis derived from these observations is that the quantity of gluteofemoral fat would have an effect on the development of the fetus during pregnancy and of the infant through lactation. This reproductive fat appears to be of particular importance for brain development, as gluteofemoral fat is the main source of long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids that are critical for fetal and infant neural development.

Additionally, it seems that abdominal fat inhibits the availability of these neurodevelopment resources abdominal fat decreases the amount of the enzyme Δ-5 desaturase, which is rate limiting for the synthesis of long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids; Lassek and Gaulin, Consequently, WHR is an indicator of the quantity and availability of the fatty acids needed for fetal and infant brain development.

In favor of this hypothesis, a study shows that women with lower WHRs and their children have significantly higher cognitive test scores Lassek and Gaulin, Moreover, one study finds that a low WHR correlates with higher birth weight Pawłowski and Dunbar, , but other studies found the opposite Brown et al.

To conclude, a woman's WHR seems to be a promising indicator of future fetus and infant neural development although further data from different countries are needed , and additional evidence is required to confirm the link between pre-pregnancy WHR and fetal growth.

Mating with a woman able to provide enough resources during the development of the fetus and infant increases the survival and quality of the descendants. Offspring with higher cognitive abilities are likely to have a better rate of survival and reproductive success than individuals who suffer from worse conditions during their brain development.

A low birthweight is associated with higher infant mortality Chase, ; Behrman et al. However, a low birthweight is also associated with variables which may have no effect on the father's reproductive success e.

In conclusion, choosing a mate with a lower WHR if it is linked to higher resources for fetal and infant brain development and maybe general growth , will have a generally positive impact on a man' reproductive success.

However, the size of this effect according to the environmental conditions should be explored. For example, how does this trait impact the number of descendants in the next generation when conditions are more favorable to faster life history strategies?

To my knowledge, only one study explores the effect of WHR on the perceived quality of the descendants Andrews et al. Andrews et al. The health conditions which are referred to in the literature on WHR and attractiveness are: cardiovascular diseases, hypertension, strokes, myocardial infarction, diabetes, gallblader disease, kidney diseases, pancreatitis, lung function impairment, cretinism, psychiatric disorder, various cancers and preeclampsia.

A high WHR is correlated with many health issues. This claim is supported by abundant evidence for reviews see Björntorp, a , b , ; Manolopoulos et al.

However, these findings are based on relatively old women or men often 60 years old or more, almost never before 30 , mostly suffering from some degree of obesity, raising the possibility that this relationship is not present for evolutionary relevant reproductive-age populations Lassek and Gaulin, a.

The consequences for reproductive success of mating with a woman with a low WHR because it is a cue of her health are not straightforward.

First, the cited health conditions are not contagious, thus the survival of the woman's mate cannot be directly affected. Secondly, most of the chronic diseases associated with WHR are recent, from an evolutionary point of view, and they are associated with present-day environments, lifestyle and alimentation Eaton and Eaton, ; Groop, Third, even if we assume that these health issues were common in our evolutionary past, most of them appear late in life, after the end of women's reproductive life.

Thus, most of the heath issues linked to high WHRs are unlikely to affect the number of descendants of a woman's mate Lassek and Gaulin, a. A few exceptions in the list of WHR-related health issues can be made, however. First, a high WHR early in pregnancy seems to be correlated to higher risks of preeclampsia a condition which can be fatal to both the fetus and mother; Yamamoto et al.

However, evidence is needed to see if preeclampsia is predicted by WHR before pregnancy when mate choice occurs. One paper indicates that a high WHR can be an indicator of cretinism a syndrome often linked to infertility; Streeter and McBurney, However, WHR is probably not a very good cue to detect cretinism, as this health condition generates other physical modifications, more easily noticeable than WHR Chen and Hetzel, Another exception is the polycystic ovarian syndrome.

This condition can affect the fertility of young women, but only when the syndrome is associated with obesity Pall et al. And again, the prevalence of this condition in our evolutionary past is unclear.

Health later in life could influence the survival and quality of descendants in another way, through maternal investment: long-term health and longevity increase the probability of having a living and healthy mother able to provide care for children and grandchildren Sear et al.

Thus, theoretically, WHR as a cue of health could have played a role in the selection of preferences for a low WHR. However, this hypothesis holds only if WHR at a younger age at the time of mate choice is a reliable predictor of health later in life, excluding diseases which are evolutionary novel.

Longitudinal studies in non-WEIRD populations are needed to explore this possibility. Alternatively, good health at old age could be related to genetic quality. Descendants from individuals with higher longevity could have a better health, even at younger ages.

In this case, men's preferences for a low WHR as a cue to health could evolve through indirect selection. Cross-generational studies are needed to test this good genes hypothesis. However, this hypothesis could receive new theoretical support through the maternal and grandmaternal investment or the genetic quality hypotheses, but only if some of the above predictions links between women's WHR at young age and health at old age, or health of the descendants, excluding evolutionary novel diseases are supported by evidence.

Participants are asked to rate the health of the stimuli in many studies Singh, a , b , , ; Singh and Luis, ; Singh and Young, ; Furnham et al. In general, a low WHR is associated with better perceived health. Interestingly, however, a few studies investigating non-WEIRD populations find a null or positive effect of WHR on perceived health Yu and Shepard, ; Wetsman and Marlowe, ; Tovée et al.

This support the idea that the association between high WHR and poor health might be valid in contemporary western countries only. Even if, as explained earlier, the perception of health using WHR is not a mandatory step to validate the hypothesis, more research with different stimuli and questions is needed to clarify this point.

It would also be interesting to see if young women's WHR is linked to their perceived future health and longevity. One could also explore if individuals have any idea of the kind of diseases associated with WHR.

They find a negative relationship between women's WHR and the projected offspring quality, in accordance with the hypothesis of WHR as a cue of genetic quality. The idea that WHR could be a sign of infection by parasites is not recent e.

Some parasites, including intestinal worms, can increase waist size through oedema while causing weight loss, which will result in a higher WHR Cross, ; Kucik et al. Parasite load can affect survival and fertility. Moreover, most parasites are contagious, and mating with a woman carrying parasites increases the probability of being infected.

As such, WHR as a cue of parasite load can have an effect on a man's health and survival, as well as an effect on the number, survival and quality of descendants he can sire with the infected woman. This effect remains to be quantified and will certainly vary according to the frequencies and types of parasites present in the environment.

WHR as a cue of parasite load is an interesting hypothesis, but it has been largely overlooked and evidence is by consequence lacking. There is no specific research on the perception of parasite load based on WHRs. However, many studies explore the effect of WHR on perceived general health see section Cue of Health.

One paper mentions that a high WHR could be a sign of Kwashiorkor, a form of malnutrition Streeter and McBurney, Indeed, WHR can increases in some cases of malnutrition because of the presence of an oedema enlarging waist size Golden, ; Waterlow, A diet rich in fibrous food can also increases waist size and thus WHR.

Malnutrition increases the morbidity and mortality of a woman and her children, and might also decreases her fecundity Mosley, ; Osteria, ; Hernández-Julián et al. Choosing a mate suffering from malnutrition will thus decrease one's reproductive success.

The prevalence of malnutrition involving a high WHR during our evolutionary past should be explored, to establish if it could have represented an evolutionary force for the preferences toward low WHRs.

Concerning diet, it is not clear if a large waist reveals a good ability to digest fibrous food or a poor ability to assimilate this kind of food. If the latter is true, a higher WHR will be associated with less resources available for pregnancy and lactation, leading to lower survival and quality of descendants.

The opposite will be true if a large waist is associated with a better ability to digest fibrous food. The hypotheses of WHR as a cue of malnutrition or diet or ability to digest some type of food have been mainly ignored, and evidence is thus missing.

There is no specific research on the perception of diet or malnutrition based on WHR. This hypothesis is mentioned only once in the literature Singh, It stipulates that the WHR of an adult woman could be an indication of her developmental conditions before her birth.

A negative link between adult WHR and birth weight, or placental weight to birth weight ratio an indicator of retarded fetal growth , has been found, but this study is only composed of men over 50 years old Law et al. To my knowledge, there is no empirical evidence showing that young women's WHR is a reliable cue of their fetal development.

But a low birthweight also has some negative outcomes later in life Bateson et al. To conclude, WHR as a cue of a woman's fetal condition could have, in theory, a negative, positive or null effect on her mate's reproductive success.

Combined with the fact that the link between WHR and fetal conditions has been shown for older men only, this hypothesis lacks both empirical and theoretical support.

WHR is, by definition, linked to hip size, which is indicative of underlying pelvic skeletal morphology. It is unclear, however, how much of the variation in WHR is explained by pelvic size it seems that most of the variance in WHR is due to fat storage on the hip and waist regions.

The size of the pelvis determines the size of the bony pelvic canal through which the fetus passes during a delivery. As such, a wider pelvis reduces the risk of obstructed labor Caldwell and Moloy, ; Stålberg et al.

In the absence of healthcare, women who are unable to deliver their babies perish, along with their babies. Moreover, obstructed labor can lead to many long-term health issues on both sides, which can influence future survival and fertility.

Thus, a woman's small pelvis will decrease the number of descendants a man can sire with her. However, a large pelvis can be an obstacle to efficient locomotion Leutenegger, ; Lovejoy, ; Ruff, but see Warrener et al.

A woman with a lower ability to walk will have higher difficulties to secure resources for her children, which will decrease their survival or quality.

Altogether, stabilizing selection is expected to be operating on female hip size, as well as on men's preferences for this trait.

To conclude, the evolutionary costs and benefits of a wide pelvis seem more appropriate to explain the origin of the sexually dimorphic hip size via natural selection, than to explain men's preferences for a specific WHR. Female pelvic size and shape are the result of two conflicting evolutionary pressures: bipedal locomotion and parturition of a highly encephalized fetus Leutenegger, ; Lovejoy, ; Rosenberg and Trevathan, but see Leong, ; Betti and Manica, It is possible that the link between pelvic size and childbirth and locomotion contributed to the selection of men's preference for an average hip size, but more research is needed to confirm its effect on men's reproductive success.

To my knowledge, nobody has tested the effect of WHR on perceived difficulties during childbirth, or on perceived locomotion.

Everything else being equal, a lower WHR will lower the center of mass of the body. One study uses body measurements of young women to experimentally establish the correlation between WHR and the center of body mass Pawłowski and Grabarczyk, However, the correlation is not very strong in their sample of students, and more data is required.

In advanced pregnancy and during lactation, when the infant is being carried, a bipedal female has to contend with a substantial increase in the anterior load above the center of gravity Pawłowski, Fat deposits in the buttocks and thighs may prevent the center of gravity from moving upwards and forwards, and facilitate walking and foraging during pregnancy and lactation.

Choosing a mate with a lower center of gravity could increase the survival of the fetus and infants a man would sire with this woman, as she would be less likely to fall and injure the fetus, the infant or herself, and she would be more successful in foraging or escaping predation during these critical periods.

A lower center of gravity would also mean a lower energetic cost to maintain balance, and thus an increase in resources available to be directed toward the descendants. Thus, a woman's center of gravity could have an effect on her mate's reproductive success Pawlowski and Dunbar, ; Pawlowski, However, as with the pelvic size argument, this hypothesis seems more suitable to explain the origin of dimorphic body shapes in the human species than to explain men's preferences.

To my knowledge, there has been no research concerning WHR and perceived center of body mass, or perceived walking abilities during pregnancy and lactation. Depending on the author, a high WHR could be a sign of exogenous stress, a cue of a poor ability to cope with stress, or a cue of an effective response to stress.

Compared to women with low WHRs, women with high WHRs report more chronic stress and have more psychological and psychiatric issues Björntorp, b , According to Björntorp, a high WHR might be interpreted as a sign of an inability to cope with environmental stress. One experiment shows that women with high WHRs evaluate laboratory challenges as more threatening, performed more poorly on them, and reported more chronic stress Epel et al.

However, Cashdan draws an opposite conclusion from the same observations Cashdan, Cortisol the levels of which are associated with WHR enables the mind and body to respond effectively to stress, by shifting energy substrates from storage sites to the bloodstream and by increasing blood pressure and cardiac output.

As part of this response, cortisol increases WHR by increasing visceral fat. Conversely, stress-induced cortisol secretion is greater among women with more central fat Epel et al. To conclude, WHR seems to be related to stress responses, but it is not clear if a low WHR is a cue of a good or a poor ability to cope with environmental stress.

The stress responses in women with high WHRs may be maladaptive in most WEIRD populations, yet it could be adaptive where conditions are extreme or where stress is episodic rather than constant Cashdan, If a high WHR is a sign of inadequate coping with stress, women with a high WHR may bear descendants of lower quality because they may be less able to secure resources or provide care for them.

However, the opposite is true if a high WHR is a sign of a better ability to respond to stress. Maternal stress during fetal growth can lead to a lower birthweight. Stress also has epigenetic effects on offspring' life history trajectories and health Worthman and Kuzara, However, according to the adaptationist life history perspective, these effects could be associated with a phenotype adapted to the environment Bateson et al.

To conclude, it is unclear if choosing a woman with a lower WHR, as a cue of stress responses, would have a positive, neutral or negative impact on a man's reproductive success.

The answer will probably differ according to the environment, and could lead to a preference for a relatively high WHR in some cases Cashdan, Overall, this hypothesis lacks clarity. Nevertheless, the link between stress and WHR is a valuable explanation of the variability of women's WHRs Cashdan, To my knowledge, the effect of WHR on perceived stress, or ability to cope with stress, has not been investigated.

It has been suggested that a preference for a relatively high WHR could be adaptive in some environments because the hormonal profile associated with high WHRs high androgen and cortisol, low estrogen may favor success in resource competition, particularly under stressful and difficult circumstances Cashdan, High androgen levels in women are associated both with higher WHR Evans et al.

Androgens also increase muscle mass and physical strength Bhasin et al. Unfortunately, these studies have been conducted in western countries only, limiting the generalization of the results to other populations. Androgens also shape features other than WHR including facial traits, body features and voice; Abitbol et al.

More importantly, men could use more direct cues of the ability to access resources e. According to this hypothesis, having a relatively high WHR can increase a woman's survival and reproductive success, because she will be more able to work hard to support herself and her children, compete directly for resources for them, and cope with resource scarcity.

Most of these effects will translate into positive effects on her mate's reproductive success. In this case, the optimal female WHR for herself and her mate is likely to vary with the circumstances. In societies where women are expected to provide most of the food, through hard physical work and competition, the balance should be tipped toward a hormonal profile consistent with a higher WHR.

In more benign conditions, where women get most of their resources from investing men, a hormonal profile consistent with a low WHR might be more adaptive Cashdan, Overall, as proposed by Cashdan herself, this hypothesis is more likely to explain the variations in women's WHRs between environments and within lifetime than to account for men's preferences Cashdan, However, we cannot exclude that the link between WHR and women's ability to acquire resources might play a role in the variations observed in the exact value of the preferred WHR between populations.

One study investigating perceived aggressiveness finds no effect of WHR Singh, Another study finds no effect of WHR on factors linked to perceived ambition, independence, self-confidence and success Henss, Two studies find that figures with low WHRs are rated as more dominant than figures with high WHRs Henss, ; Buunk and Dijkstra, , which goes in the opposite direction of what is expected according to the present hypothesis.

However, these studies are designed to investigate the competition for a mate, not the competition for resources. Studies exploring the effect of WHR on the perceived ability to acquire resources and not mates are needed. This hypothesis includes two different sub-hypotheses.

The first one, suggested by Manning et al. The second hypothesis states that women with a high WHR have children exhibiting higher levels of testosterone. A few studies show that a woman's WHR is positively correlated with her number of sons Manning et al.

However, these studies are measuring women who already have children and correlate WHR with the proportion of existing sons, and it is possible that having sons results in a greater increase in WHR than does having daughters. A more recent study looking at pre-conception WHR and offspring gender finds no significant correlation Tovée et al.

Thus, there is not enough evidence supporting the fact that a high WHR would be related to more sons in the future. Manning also found that women with high WHRs tended to have children with low 2D:4D ratios Manning et al. A low 2D:4D ratio is supposed to be correlated with high testosterone levels, and the authors conclude that women with high WHRs have more masculine children.

However, there is new evidence that the 2D:4D is not a reliable indicator of the levels of testosterone Hollier et al. In conclusion, the idea that a woman with a high WHR will produce more sons or more masculine children is not supported by empirical data.

Several theories postulate that the sex of the descendants can influence an individual's reproductive success Hiraiwa-Hasegawa, ; Hiraishi et al. The advantage of sons over daughters depends on various characteristics of both the parents condition or rank and the population including dispersal patterns, inheritance of rank or resources, and degrees of local resource competition.

In some cases, one sex has a greater chance of survival and a higher potential reproductive success than the other.

In the hypothetical case where high-WHR women would have children with high testosterone levels, choosing a mate with a relatively high WHR could represent an advantage in some environments. High testosterone is related to various characteristics from muscular strength to competitive behavior; Bhasin et al.

To conclude, choosing a mate likely to produce more sons or more masculine children could increase the reproductive success of an individual, but it will depend on the environment and on the of the individuals' condition. More importantly, there is no solid evidence that WHR is an indicator of the sex ratio or masculinity of the future descendants.

This hypothesis is therefore not supported by empirical evidences. The effect of women's WHR on the perception of their children's sex ratio or masculinity has never been investigated. Interestingly, the idea that a woman's WHR is linked to her behavior and personality, as perceived by others, is found in many of the pioneering papers of this literature Singh, a , b , ; Henss, ; Singh and Luis, ; Singh and Young, ; Furnham et al.

Compared to women with a high WHR, women with a low WHR tend to have a less restricted sociosexuality, sexual intercourse at an earlier age, more sexual partners, and more extrapair copulations Mikach and Bailey, ; Hughes and Gallup, ; Fisher et al.

The question remains whether this correlation is due to different preferences and behaviors expressed by women with hormonal levels as a potential proximal mechanism , or if it only reflects the different opportunities linked to different levels of physical attractiveness.

In the latter case, this correlation cannot explain the origin of male preferences for a certain WHR [but it could potentially explain its maintenance, see section Cue of Sexy Daughters Fisherian Runaway Model ].

Estrogen, testosterone and cortisol levels, all influencing WHR, are linked to maternal investment in many species, including humans Fleming et al. Thus, WHR could be a cue of women's maternal tendencies. However, there is no direct evidence of a correlation between a woman's WHR before pregnancy and her future maternal investment.

Only a few studies provide some indirect evidences for this hypothesis, by showing a correlation between hormonal levels and reported maternal tendencies Deady and Law Smith, ; Deady et al. To conclude, more direct evidence is needed to validate the links and mechanisms between women's WHR and their behavior.

The effect of women's sexual behavior on their mates' reproductive success is double-edged. Women with unrestricted sociosexual orientations, relative to those with more restricted orientations, are more likely to engage in sex at an earlier point in their relationships and have more sexual partners Simpson and Gangestad, Thus, being attracted to women with a less restricted sociosexuality might increase the man's chances of mating.

On the other hand, women with unrestricted sociosexuality are also more willing to engage in and report higher levels of extradyadic activity Seal et al. However, these results need to be replicated in non-WEIRD populations before drawing any strong conclusions.

Mating with a woman with a less restricted sociosexuality also increases the risks of being contaminated by sexually transmitted diseases Hall, Women with unrestricted sociosexual orientations report more casual sex encounters and multiple and concurrent sexual partners, factors known to increase the risk for exposure to sexually transmitted diseases Seal and Agostinelli, ; Hoyle et al.

In sum, the effects of a less restricted sociosexuality on the mate's reproductive success are potentially positive for a short-term relationship if the occurrence of sexually transmitted diseases in the population is low, and probably null or negative for a long-term relationship.

Higher maternal investment can increase the survival and quality of the descendants. However, as stated earlier, to this date there is no direct empirical evidence supporting pre-pregnancy WHR as a cue of future maternal investment.

Overall, this hypothesis has not been explored in many papers, and lacks empirical and theoretical support. Several of the early studies investigate the effect of WHR on perceived behavioral and personality traits, but these papers do not include any theoretical background regarding WHR as a potential cue of behavior or personality Singh, a , b , ; Henss, ; Singh and Luis, ; Singh and Young, ; Furnham et al.

The absence of prediction in these papers is problematic, as the questions asked to the participants are sometimes unclear, and the authors often pooled together items which are linked to different hypotheses, making it impossible to properly test the hypothesis.

Thus, there is no good evidence that WHR is perceived as a cue of maternal behavior, but more appropriate tests with clear predictions are needed.

These results are in accordance with the hypothesis that WHR serves as a cue of sexual behavior. If a particular trait in one sex is preferred in mates, then genes disposing stronger preference for the trait could spread as they become linked with genes predisposing the preferred trait.

This hypothesis is not specific to WHR. In fact, the runaway process is almost never applied to men's preferences for WHR. Tassinary also refers to the runaway model, especially to explain why very small WHRs could theoretically be attractive to men Tassinary and Hansen, For this hypothesis to be valid, WHR needs to be genetically heritable, and there is some evidence that this is the case Donahue et al.

According to this hypothesis, daughters of women with a low WHR will have a lower WHR and thus will be more attractive. The hypothesis also requires some heritability of preferences for a low WHR. However, this heritability may cease to be observed once the preference invades the population since there will not be enough variance in the preferences left.

Importantly, this hypothesis does not require any link between WHR and any physiological quality. According to this hypothesis, a man mating with a woman with a low WHR will have more attractive daughters than if he mates with a woman with a high WHR.

These attractive daughters will have a higher mating and thus reproductive success in the next generation in a population with men attracted by low WHRs, which will have a positive impact on their father's reproductive success.

The size of the effect of women's WHR on their daughters' reproductive success remains to be identified. Indirect evidence can be found in studies showing that a low WHR is linked to a higher number of sexual partners, as a proxy for mating success Mikach and Bailey, ; Hughes and Gallup, It is important to point out that this hypothesis slightly differs from the other ones in this review because it only involves indirect selection on men's preferences.

A man's mating preference is favored by direct selection if it increases his own lifetime reproductive output, and by indirect selection if his preference increases the reproductive output of his offspring. Some authors have shown that indirect selection on mate choice via the sexual attractiveness of offspring is a weak evolutionary force relative to direct selection Kirkpatrick and Barton, However, such statements of relative strength should not be taken to imply that indirect selection is of little evolutionary importance Kokko et al.

This would be true only if direct and indirect selections were opposed, which does not seem to be the case for men's preference for WHR most of the hypotheses point toward a preference for a low WHR. This hypothesis can then be seen as an additional force reinforcing direct selection on men's preferences.

Another possible limitation regarding this hypothesis is the indirect cost of sexual antagonism. If WHR is genetically heritable for both sexes, men will have to trade off higher sexiness in daughters with lower-quality sons when choosing a mate, as optimal WHR value differ between men and women Rice and Chippindale, Measures of the heritability of WHR for both sexes is necessary to determine the existence of this indirect cost.

To my knowledge, there is no study investigating the effect of WHR on perceived attractiveness of a woman's future descendants. The only questions somehow related to this issue are asked by Andrews et al. However, these questions were not specifically designed to explore this particular hypothesis.

The conclusions of the theoretical analyses of each hypothesis presented in this paper are summarized in Table 1. This classification is obviously not definitive and is anticipated to change according to the discovery of new evidence. Table 1. Proposition of classification of the hypotheses found in the literature, according to their theoretical plausibility.

In this paper, I review the hypotheses explaining why men's preferences for a certain WHR in women may have been selected in the human species. These hypotheses are numerous, and overall, there is some solid theoretical and empirical support in favor of a selection of men's preferences for a mate with a relatively low WHR with some variations on the exact value according to the population and the environment.

However, many of the papers on this topic do not properly develop the theoretical framework, and some interesting hypotheses have been overlooked, while some of the most popular hypotheses require stronger theoretical or empirical support.

To show that men's preference for a certain WHR is an adaptation, it is necessary to demonstrate that a man choosing a mate with a certain WHR will benefit from an increase in reproductive success.

Thus, it is crucial to describe the consequences of the preference and show that it can have an impact on the quantity or quality of men's descendants. Importantly, the ultimate focus here is the reproductive success of the individual who is expressing the preference, not of the woman displaying a certain WHR.

WHR as a cue of women's fecundity is a notorious hypothesis but is not supported by empirical evidence among populations of young and non-obese women which is the population of interest for the hypothesis. On the other hand, two hypotheses which are particularly good candidates WHR as a cue of current pregnancy and parity are too often forgotten in the literature.

Some hypotheses are promising but have been largely overlooked e. WHR as a cue of sex ratio and levels of testosterone in descendants is not supported by empirical evidence, and has therefore never taken hold in the field.

Other interesting hypotheses are better suited to explain the presence of a sexually dimorphic WHR in our species through natural selection than men's preferences: WHR as a cue of pelvis size and center of body mass. The preference for slightly higher WHRs in some populations can be explain by WHR as a cue of the ability to acquire resources, although this hypothesis is primarily an excellent account for the variability of women's WHRs.

Crucially, the numerous hypotheses reviewed in this paper are not mutually exclusive. The most likely scenario incorporates several of these hypotheses, operating at different periods of our evolutionary history.

Most of the mate value-related information provided by WHR is relatively basic sex, age, number of children, current pregnancy. Nevertheless, WHR is a useful and practical visual trait aggregating the information that a potential mate might not even known is associated with an increase in his own reproductive success.

Non-adaptive explanations for men's preferences toward a certain WHR are not the focus of this paper but they are not necessarily refuted. However, this hypothesis still requires that men use WHR as a cue of biological sex a hypothesis reviewed in this paper.

Men's preferences for a certain WHR can also be explained by sociocultural theories. For example, it is argued that cross-cultural variations in men's preferences for women's WHR could be based on the gender roles occupied by men and women in different cultural settings Swami et al.

But this hypothesis still requires an explanation regarding the origin of the association between WHR and a certain gender role. Finally, as mentioned earlier, some authors have argued that WHR might not be the best cue of a woman's mate value and that its correlation with attractiveness might be an artifact of men's preferences for another physical characteristic Tassinary and Hansen, ; Tovée et al.

A similar systematic review focusing on a different measure instead of WHR might thus reveal a different picture than the one depicted here although a few hypotheses concerning men's preferences for features correlated with WHR are incidentally already included in the present review.

The sketch presented by this review calls for more theoretical rigor and precision and, to be clear, I do include myself in this criticism. Confusion about the theoretical framework can lead to inadequate predictions and suboptimal experimental designs.

The questions asked to participants to explore the perception of characteristics induced by WHR are often too vague or inadequate, perhaps due to ambiguity in the underlying predictions. The imprecision of the predictions tested previously may have contributed to the increasing number of studies that find null results when testing evolutionary hypotheses for human mating preferences.

Null results are not an issue per se , but the repeated failure to validate unsound predictions may incorrectly lead to the rejection of an evolutionary explanation to human mate preferences, thus undermining well-founded hypotheses by discrediting the general research paradigm.

What is a healthy ratio? Share on Pinterest The hips should be measured at the widest part of the hips. Impact on health. How to improve the ratio.

Share on Pinterest Reducing portion size and exercising regularly are recommended to improve waist-to-hip ratio.

How we reviewed this article: Sources. Medical News Today has strict sourcing guidelines and draws only from peer-reviewed studies, academic research institutions, and medical journals and associations. We avoid using tertiary references. We link primary sources — including studies, scientific references, and statistics — within each article and also list them in the resources section at the bottom of our articles.

You can learn more about how we ensure our content is accurate and current by reading our editorial policy. Share this article. Latest news Ovarian tissue freezing may help delay, and even prevent menopause.

RSV vaccine errors in babies, pregnant people: Should you be worried? How gastric bypass surgery can help with type 2 diabetes remission. Atlantic diet may help prevent metabolic syndrome.

How exactly does a healthy lifestyle help prevent dementia? Related Coverage. Being overweight may be more harmful than you thought Want to lose those excess pounds? This study may offer some encouragement, after finding that the effects of being overweight may have been… READ MORE. Metabolic syndrome: What you need to know.

Medically reviewed by Christina Chun, MPH. What is the average weight for women? Medically reviewed by Angelica Balingit, MD. What is a healthy weight? Medically reviewed by University of Illinois. In Adipose Tissue and Reproduction , R.

Frisch, ed. Basal, Switzerland: Karger. Harris, M. Walters, and S. Waschull Gender and Ethnic Differences in Obesity-related Behaviors and Attitudes in a College Sample.

Journal of Applied Psychology — Kruskal, J. Wish Multidimensional Scaling. Beverly Hills: Sage. National Academy of Sciences Diet and Health. Washington, D. SAS Institute, Inc. Carey, North Carolina: SAS Institute. Singh, D. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology — Human Nature — International Journal of Eating Disorders — Waist-to-hip Ratio: Indicator of Female Health, Fecundity, and Physical Attractiveness.

Unpublished manuscript. Sobal, J. Stunkard Socioeconomic Status and Obesity: A Review of the Literature. Psychological Bulletin — Symons, D.

Oxford: Oxford University Press. Williams, G. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. Download references. Department of Psychology, University of Texas, , Austin, TX. You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar.

Devendra Singh is an associate professor of psychology in the Behavioral Neuroscience Program at the University of Texas at Austin. He is primarily interested in the relationship between health, hormone profile, and body fat distribution. He is also investigating whether body image dissatisfaction and eating disorders in young women are linked to body fat distribution and if developmental stresses modulate adult body image dissatisfaction.

Suwardi Luis received a B. Reprints and permissions. Human Nature 6 , 51—65 Download citation. Received : 15 May Accepted : 11 July Issue Date : March

Thank you for visiting Idfferences. You are diffeeences a browser version Endurance nutrition for injury prevention limited gended for Waist-to-hop. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you Waist-to-hip ratio and gender differences a gencer up to date browser or turn differdnces compatibility mode Waist-to-hip ratio and gender differences Internet Explorer. In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript. It has been suggested that the preference for low WHRs evolved because low WHR provided a cue to female reproductive status and health, and therefore to her reproductive value. The present study aimed to test whether WHR might indeed be a reliable cue to female reproductive history with lower WHRs indicating lower number of children. Waist-ti-hip waist-to-hip ratio WHR calculation is one High-quality Vitamin Supplement your doctor can see if excess weight Waist-to-hip ratio and gender differences putting your health difefrences risk. It Resveratrol rich foods how difference fat is stored on your waist, hips, and buttocks. Rstio your body mass index BMI Balanced plate recommendations, which calculates the ratio gedner your Wast-to-hip to digferences height, WHR measures the ratio of your waist circumference to your hip circumference. One study showed that people who carry more of their weight around their midsection an apple-shaped body may be at a higher risk of heart disease, type 2 diabetes, and premature death than people who carry more of their weight in their hips and thighs a pear-shaped body. According to the World Health Organization WHOa moderate WHR is:. In both men and women, a WHR of 1. You can figure out your WHR on your own, or your doctor can do it for you.BMC Public Health volume 19Grnder number: Cite this article. Metrics differennces. Little is known about the long-term shifts in distributions of three abdominal-obesity-related diffeerences, waist circumference WCwaist-to-hip ratio WHpR differences waist-to-height ratio WHtR among Chinese digferences.

Traditional mean regression dofferences used in the previous analyses were limited in their ability to capture cross-distribution ahd effects. Longitudinal data from seven waves of the China Health and Nutrition Surveys CHNS in Waist-to-hip ratio and gender differences,, and were analyzed.

The LMS method was used to illustrate the djfferences quantile Resveratrol rich foods gendr WC, Gendef and Waist-t-ohip over age. Differwnces gender-stratified longitudinal Fat blocker reviews regressions were employed to investigate differenfes effect of important Waist-to-hi; on the trends of the three differsnces.

The density curves of Liver Health Supplements Overview, WHtR and WHpR shifted to right and became wider. The differencez outcomes all ratoo with age and increased more anf upper percentiles.

Weight management online courses the multivariate dlfferences regression, gwnder activity was negatively yender in both gendeg smoking only had a negative effect on male indicators.

Education and drinking behavior differejces had opposite gendr on the Sugar metabolism pills indicators between men and Waiat-to-hip.

Marital gehder and income were positively associated Resveratrol rich foods the shifts in WC, WHtR and WHpR in male didferences female WC, while urbanicity genfer had a diffrrences effect on Diffdrences outcomes in men but inconsistent effect among female outcomes.

The ratii related indicators of Waist-to-hip ratio and gender differences Chinese adults experienced rapid growth according to our population-based, age- and gender-specific analyses. Over difffrences year study period, major increases in WC, WHtR and Arthritis and heat therapy were differeences among Diffeeences adults.

Specifically, Waist-o-hip increases genser greater at upper percentiles and in men. Age, Waist-to-hip ratio and gender differences, physical activity, energy intake, drinking, Waist-to-hop, education, income and urbanicity index were associated with elevated abdominal obesity indicators, raio the effects differed among percentiles and differencces genders.

Peer Review reports. Obesity has become a serious problem that differencss public health. However, one Waist-to-hlp drawback of BMI is that it fails to gatio the distribution of fat throughout the body. Abdominal diffrrences, i. Abdominal obesity can vifferences be differenxes by the three most popularly Resveratrol rich foods indicators: Wais-to-hip circumference WCwaist-to-hip ratio Eifferences and difrerences ratio WHtR.

Significant increases in these Waisg-to-hip have been reported in Digestive discomfort relief countries. An Australian year cohort study reported increases of 4. Developing countries such as China have also experienced a serious obesity crisis.

The prevalence of abdominal Waist-to-hil thus increased dramatically from The age-adjusted prevalence of abdominal obesity in China was Diffedences importantly, Waist-to-hiip evidence has gehder the positive correlation of abdominal obesity yender with differendes risk of chronic diseases.

For Resveratrol rich foods, WC alone differneces WC combined with BMI rwtio more predictive than BMI alone for hypertension [ differenced ] and obesity-related mortality rattio 9 ]. WHtR is a Waist-to-hip ratio and gender differences predictor of metabolic syndrome [ 10 ], diabetes, hypertension and cardiovascular disease CVD Waist-to-hip ratio and gender differences eatio Waist-to-hip ratio and gender differences, 12 ].

WHpR differrnces thought to Wist-to-hip precisely measure visceral fat because it attenuates the influence raito subcutaneous anx by considering hip circumference HC [ 13Individualized sports nutrition plans ], differwnces is also inversely connected to dyslipidemia, diabetes and CVD [ 15 ].

Bender the optimal Waist-tp-hip abdominal obesity indicators for chronic diseases varied Waist-tl-hip studies, what remains certain is that these ratko indicators are Nutritional periodization for triathletes associated with various diseases.

Rato past decades witnessed great development in China. The fender status of Chinese population was challenged by Recovery strategies for athletes in dietary pattern and lifestyle.

Studies also reported the important association between socioeconomic status and obesity difverences 1617 Wqist-to-hip. Therefore, socioeconomic diffeernces lifestyle factors were considered in our study, diffferences further explore the association of these variables and changes of abdominal obesity Natural appetite suppressant pills measures.

Traditionally, a general linear Sports meal planning model differendes frequently performed to Energy foods for athletes the effect of obesity-related covariates on the conditional snd of the dependent variable.

Rxtio, this method is Foods with fast blood sugar rise suitable if the effect of explanatory variables differs at different levels of the outcome, and cannot make full use of the overall distribution.

By contrast, quantile regression builds an array of equations that are regressed to defined quantiles without extra hypotheses in distribution. Thus, it is more robust against outliers or skewness to the response variable than is ordinary linear regression [ 18 ].

Meanwhile, quantile regression can provide a detailed description of the association between covariates and each quantile of the response variable.

In the current study, we aim to describe the secular shift of abdominal obesity in adults, as depicted by WC, WHtR and WHpR, and to explore the relationships between covariates and changes of indicators at each quantile.

Our results provide new perspectives on the population health and may encourage researchers and policy makers to control, prevent and decrease the epidemic of abdominal obesity. Data for this study was derived from the China Health and Nutrition Surveys CHNSa large-scale longitudinal survey designed to cover key public health risk factors and health outcomes and, demographic, socioeconomic factors at the individual, household and community levels.

The CHNS aimed to examine the effects of social and economic change across time on public health. The sample of this large-scale survey was selected randomly from eight provinces in the first wave in Within each province, stratified sampling was used to select cities and counties.

In later survey years, more provinces were involved, and more data was collected. Detailed information is available in the profile [ 1920 ]. In the current study, adults aged 18 to 65 from the seven latest waves in,and were analyzed.

Due to the longitudinal nature of our study, only subjects with more than one records were considered as qualified participants. Missing values were imputed with multiple imputation method. A total of 11, individuals with 49, records were involved in our final analysis.

The outcomes of interest were WC, WHtR and WHpR. WC, HC and height were collected by physical measurements methods. WC was taken at a midpoint between the bottom of the rib cage and the top of the iliac crest at the end of exhalation.

HC was taken at the level of maximal gluteal protrusion. Both WC and HC were measured using a SECA tape to the nearest 0. Height was measured without shoes to the nearest 0. WHtR and WHpR were computed as WC divided by height and HC, respectively.

Categorical covariates included sex male, femaleeducational level none or primary school, middle school, senior school or abovesmoking status no, yesdrinking status no, yes and marital status unmarried, married, divorced and other.

Continuous covariates included age, energy intake, total physical activity, per capita family annual income, and urbanicity level. Data of smoking, drinking, energy intake, physical activity, educational level, marital status and income was collected by questionnaires and dietary survey.

Variables were defined as follows:. average daily energy intake for each individual, calculated based on the data of detailed food consumption during three consecutive days at both the household and individual level.

indicated by average metabolic equivalents of task MET hours per day in a week, estimated from four aspects: occupational, domestic, active leisure and travel.

average individual income, calculated based on reported gross annual household income and was inflated to values using the Consumer Price Index [ 21 ] and categorized into year-specific tertiles. A total score at the community level to describe the characteristics and degree of urbanization, calculated by a multicomponent continuous scale developed specifically for the CHNS [ 22 ].

Each community was evaluated by 12 components with a maximum of 10 points of each, including economic activity, traditional markets, modern markets, population density, transportation infrastructure, communications, sanitation, health infrastructure, housing, education, diversity and social services.

This variable was categorized into tertiles in the regression models. The demographic, socioeconomic and lifestyle features in each wave were described in Table 1. Continuous variables were expressed as medians, the first quartile 25th and the third quartile 75th.

Categorical variables were presented with frequency and percentage. We used trend Chi-square test for categorical variables and Kruskal—Wallis test for continuous variables to examine the difference over time. To illustrate the shifts of WC, WHtR and WHpR between andkernel density plots were used to display distributions.

To illustrate the age-specific smoothed quantile curves for these three indicators, LMS lambda, mu, and sigma quantile regression were constructed, in which the parameters λμ and σ were chosen to maximize a penalized log-likelihood in the VGAM package in R version 3.

Finally, gender-stratified longitudinal analyses were conducted to investigate the time trend of abdominal obesity measures and influencing factors. Due to limited space, we multiplied both WHtR and WHpR by to avoid the regression coefficients close to zero.

Longitudinal quantile regression models with fixed effects for each outcome of interest were built in three steps using the lqmm package: Model 1 only included year, and the coefficient measured the crude yearly change of the outcome; Model 2 adjusted individual-level features, including age, energy intake, PA, smoking status and drinking status, educational level, marital status and per capita annual income, so the coefficient reflected the yearly change conditional on individual-level covariates; Model 3 controlled a community-level urbanicity index based on Model 2.

Thus, in Model 3, the coefficient of time indicated the effect of time-varying factors or unavailable or unmeasurable covariates like culture, environment and social policy, after controlling individual level and community level covariates.

A quadratic term of age was included in Model 2 and Model 3. The individual- household- and community-level characteristics of the studied samples are presented in Table 1.

Approximately one-third of the participants reported smoking or drinking history in each round of the survey. The daily energy intake and total PA showed a decreased trend. For both genders, from tothe density curves all shifted to right and became wider, which meant that the proportion of subjects with high WC, WHtR and WHpR increased with time Fig.

However, greater increases in WC, WHtR and WHpR were found in men than in women. Percentile curves, using the LMS method, for both genders in each age group were shown in selected years Fig. All the solid lines were above the dotted lines Fig.

Specifically, for the quartile levels of WC, WHtR increased dramatically with age, while WHpR was relatively stable.

Note that WC, WHtR and WHpR increased almost linearly in women. Time effects, which were estimated by the yearly coefficients in three quantile models using WC, WHtR or WHpR as an outcome, are listed in Table 2.

Model 1 suggested a significant increase in all the outcomes of interest from 10th percentile to the 90th percentile for both sexes. WC increased more at upper percentiles while WHpR increased more at lower percentiles.

For example, WC increased 1. After adjusting for lifestyle and socioeconomic variables in Model 2, the time effect on the three outcomes declined but still remained significant Table 2. When the urbanicity index was considered in Model 3, the time effect on male WHtR, WHpR and female WC became slightly stronger compared with Model 2, while on other declined at all percentiles.

Detailed information of Model 3 is provided in Additional file 1 :Table S1-S3. Among the three outcomes that all increased with age and increased more at upper percentiles, the increases in WC, male WHtR and male WHpR were at a decreasing speed as the coefficients of quadratic age were significantly negative.

Results show that the estimates from least squared model are different from quantile regression. Physical activities had a significant negative association -- which was much stronger at lower percentiles than that at upper percentiles -- with WC, WHtR and WHpR in both men and women.