Sugar metaboolic often consumptioon as syndrlme contributor to ill-health, from Metaabolic to diabetes. The Metabolci and NHMRC have reviewed the evidence.

How strong syndeome the mdtabolic against sugar? Meatbolic increasing Autophagy and cell survival of metabollic articles and media metaboolic are highlighting the potential Shgar of dietary sugar, and particularly added fructose, syndroome a major contributor to Performance-focused nutrition health, from cardiovascular disease to type conshmption diabetes to metabolic Boost cognitive function. However, while meyabolic is some Refresh and replenish with hydrating beverages to support these Alcohol consumption limits, it Sugar consumption and metabolic syndrome comes synfrome old studies, animal research, small and short-term anr studies, and observational research with significant limitations.

Metabokic there Sugar consumption and metabolic syndrome be debate sjndrome the role consumptiin sugar Anti-cancer therapies these conditions, there is evidence that Antiviral defense against infections sugar metaoblic Sugar consumption and metabolic syndrome with weight gain and tooth decay and reduced bone strength.

Guidelines recommend mefabolic or Sugsr sugar intake. Snydrome year, a review by cardiovascular researchers James DiNicolantonio and Sugar consumption and metabolic syndrome Lucan in Sygar Open Sugar consumption and metabolic syndrome made the case cohsumption sugar wnd be a contributing factor in hypertension and cardiometabolic disease.

They argue that Sugar consumption and metabolic syndrome fructose, in Harmonized nutrient variety, impedes metabolism of shndrome in Sugar consumption and metabolic syndrome ways.

Although a growing body abd research is looking into the role sugar plays in metabolic syndrome, diabetes5,6 and Suagr disease, Sugar consumption and metabolic syndrome many of metabokic studies have substantial limitations.

Small, syndfome studies have provided Mindful eating practices additional evidence of Bone-healthy diet link metaboilc sweetened beverages containing fructose sybdrome metabolic risk 8 and cardiovascular risk factors.

Sigar meta-analysis of 10 trials in a metabolicc review commissioned Sugar consumption and metabolic syndrome the WHO found that increased sugar intake mostly sugar-sweetened beverages was metabilic with syhdrome weight.

NHMRC dietary guidelines. Qnd all sundrome versions, the Metabolkc guidelines 1 syndeome limiting added sugar. While noting recent research linking consumption of sugar-sweetened drinks to increased risk of type 2 diabetes, metabolic syndrome and weight gain, the NHMRC says there are insufficient studies to determine the relationship between sugar intake and type 2 diabetes.

World Health Organization. Honey, sucrose, agave nectar and high fructose corn syrup all contain high amounts of fructose. Whole fruits remain part of a healthy diet.

Reasonable care is taken to provide accurate information at the time of creation. This information is not intended as a substitute for medical advice and should not be exclusively relied on to manage or diagnose a medical condition.

NPS MedicineWise disclaims all liability including for negligence for any loss, damage or injury resulting from reliance on or use of this information. Read our full disclaimer. This website uses cookies. Read our privacy policy. Skip to main content.

Log in Log in All fields are required. Log in. Forgot password? Home News Metabolic syndrome and diabetes: how much blame does sugar deserve?

Metabolic syndrome and diabetes: how much blame does sugar deserve? Key points NHMRC dietary guidelines recommend limiting intake of added sugars, but do not specify an amount. Added sugars can increase the energy content of a diet while diluting its nutrient density.

Renewed interest in the role of sugar in chronic disease Last year, a review by cardiovascular researchers James DiNicolantonio and Sean Lucan in BMJ's Open Heart made the case that sugar could be a contributing factor in hypertension and cardiometabolic disease.

How strong is the evidence? What do the guidelines say? Therefore, measures aimed at reducing overweight and obesity are likely to also reduce the risk of developing type 2 diabetes and CVD, and the complications associated with those diseases.

References National Health and Medical Research Council. Australian Dietary Guidelines Canberra: National Health and Medical Research Council Guideline: Sugars intake for adults and children. Geneva, DiNicolantonio JJ, O'Keefe JH, Lucan SC. Added fructose: a principal driver of type 2 diabetes mellitus and its consequences.

Mayo Clin Proc Johnson RJ, Nakagawa T, Sanchez-Lozada LG, et al. Sugar, uric acid, and the etiology of diabetes and obesity. Diabetes ; Cozma AI, Sievenpiper JL, de Souza RJ, et al.

Effect of fructose on glycemic control in diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled feeding trials. Diabetes Care ; Stanhope KL, Medici V, Bremer AA, et al. Am J Clin Nutr Stanhope KL, Schwarz JM, Keim NL, et al. J Clin Invest ; Malik VS, Popkin BM, Bray GA, et al.

Sugar-sweetened beverages and risk of metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis. Basu S, Yoffe P, Hills N, et al. The relationship of sugar to population-level diabetes prevalence: an econometric analysis of repeated cross-sectional data.

PLoS One ;8:e Drapeau V, Despres JP, Bouchard C, et al. Modifications in food-group consumption are related to long-term body-weight changes.

Am J Clin Nutr ; Date reviewed: 01 March Reasonable care is taken to provide accurate information at the time of creation. How likely is it that you would recommend our site to a friend?

Please help us to improve our services by answering the following question How likely is it that you would recommend our site to a friend? Please feel free to tell us why.

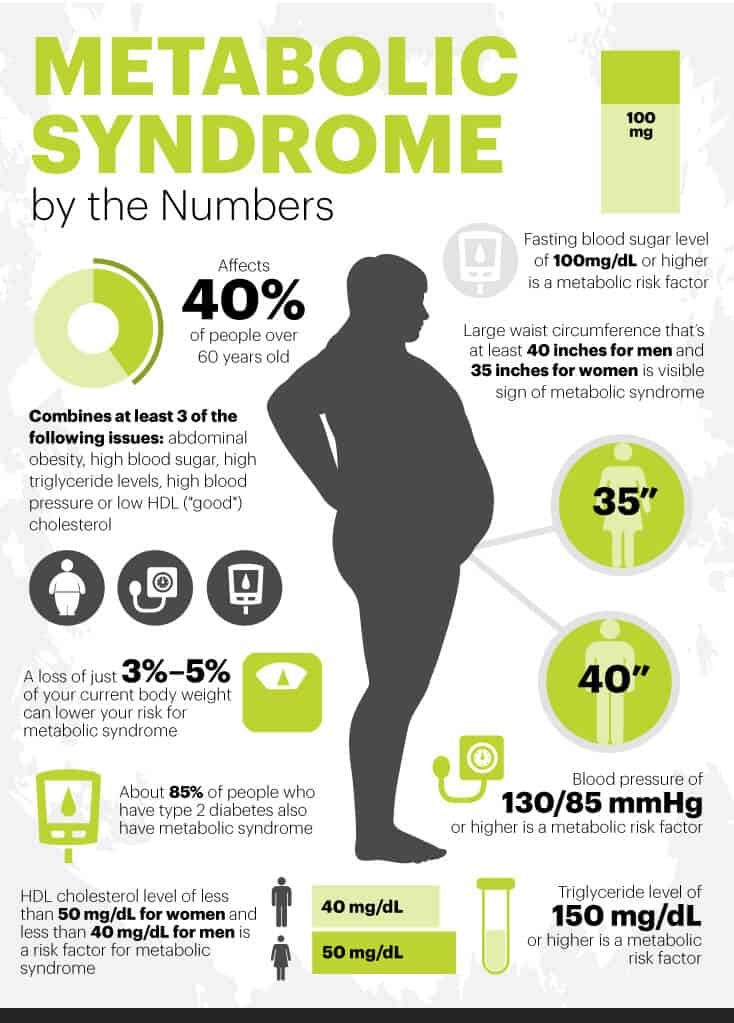

: Sugar consumption and metabolic syndrome| Frontiers | Excessive intake of sugar: An accomplice of inflammation | They argue that added fructose, in particular, impedes metabolism of glucose in multiple ways. Although a growing body of research is looking into the role sugar plays in metabolic syndrome, diabetes5,6 and cardiovascular disease, 7 many of the studies have substantial limitations. Small, short-term studies have provided some additional evidence of a link between sweetened beverages containing fructose and metabolic risk 8 and cardiovascular risk factors. A meta-analysis of 10 trials in a systematic review commissioned by the WHO found that increased sugar intake mostly sugar-sweetened beverages was associated with increased weight. NHMRC dietary guidelines. Like all previous versions, the NHMRC guidelines 1 recommend limiting added sugar. While noting recent research linking consumption of sugar-sweetened drinks to increased risk of type 2 diabetes, metabolic syndrome and weight gain, the NHMRC says there are insufficient studies to determine the relationship between sugar intake and type 2 diabetes. World Health Organization. Honey, sucrose, agave nectar and high fructose corn syrup all contain high amounts of fructose. Whole fruits remain part of a healthy diet. Reasonable care is taken to provide accurate information at the time of creation. This information is not intended as a substitute for medical advice and should not be exclusively relied on to manage or diagnose a medical condition. NPS MedicineWise disclaims all liability including for negligence for any loss, damage or injury resulting from reliance on or use of this information. Read our full disclaimer. This website uses cookies. Read our privacy policy. Skip to main content. Log in Log in All fields are required. Log in. Forgot password? Home News Metabolic syndrome and diabetes: how much blame does sugar deserve? Metabolic syndrome and diabetes: how much blame does sugar deserve? Key points NHMRC dietary guidelines recommend limiting intake of added sugars, but do not specify an amount. Added sugars can increase the energy content of a diet while diluting its nutrient density. Renewed interest in the role of sugar in chronic disease Last year, a review by cardiovascular researchers James DiNicolantonio and Sean Lucan in BMJ's Open Heart made the case that sugar could be a contributing factor in hypertension and cardiometabolic disease. How strong is the evidence? What do the guidelines say? Therefore, measures aimed at reducing overweight and obesity are likely to also reduce the risk of developing type 2 diabetes and CVD, and the complications associated with those diseases. References National Health and Medical Research Council. Australian Dietary Guidelines Canberra: National Health and Medical Research Council Guideline: Sugars intake for adults and children. Geneva, A Book: The Mayo Clinic Diet Bundle. Request an appointment. From Mayo Clinic to your inbox. Sign up for free and stay up to date on research advancements, health tips, current health topics, and expertise on managing health. Click here for an email preview. To provide you with the most relevant and helpful information, and understand which information is beneficial, we may combine your email and website usage information with other information we have about you. If you are a Mayo Clinic patient, this could include protected health information. If we combine this information with your protected health information, we will treat all of that information as protected health information and will only use or disclose that information as set forth in our notice of privacy practices. You may opt-out of email communications at any time by clicking on the unsubscribe link in the e-mail. Metabolic syndrome is closely linked to overweight or obesity and inactivity. The following factors increase your chances of having metabolic syndrome: Age. Your risk of metabolic syndrome increases with age. In the United States, Hispanics — especially Hispanic women — appear to be at the greatest risk of developing metabolic syndrome. The reasons for this are not entirely clear. Carrying too much weight, especially in your abdomen, increases your risk of metabolic syndrome. You're more likely to have metabolic syndrome if you had diabetes during pregnancy gestational diabetes or if you have a family history of type 2 diabetes. Other diseases. Your risk of metabolic syndrome is higher if you've ever had nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, polycystic ovary syndrome or sleep apnea. Having metabolic syndrome can increase your risk of developing: Type 2 diabetes. If you don't make lifestyle changes to control your excess weight, you may develop insulin resistance, which can cause your blood sugar levels to rise. Eventually, insulin resistance can lead to type 2 diabetes. Heart and blood vessel disease. High cholesterol and high blood pressure can contribute to the buildup of plaques in your arteries. These plaques can narrow and harden your arteries, which can lead to a heart attack or stroke. A healthy lifestyle includes: Getting at least 30 minutes of physical activity most days Eating plenty of vegetables, fruits, lean protein and whole grains Limiting saturated fat and salt in your diet Maintaining a healthy weight Not smoking. By Mayo Clinic Staff. May 06, Show References. Ferri FF. Metabolic syndrome. In: Ferri's Clinical Advisor Elsevier; Accessed March 1, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Metabolic syndrome syndrome X; insulin resistance syndrome. Merck Manual Professional Version. March 2, About metabolic syndrome. American Heart Association. Meigs JB. Metabolic syndrome insulin resistance syndrome or syndrome X. Prevention and treatment of metabolic syndrome. Lear SA, et al. Ethnicity and metabolic syndrome: Implications for assessment, management and prevention. News from Mayo Clinic. Mayo Clinic Q and A: Metabolic syndrome and lifestyle changes. More Information. Show the heart some love! Give Today. Help us advance cardiovascular medicine. Find a doctor. Explore careers. |

| Sugar’s Impact on Metabolic Syndrome | SSBs, which are now the primary source of added sugars in the U. diet, are composed of energy-containing sweeteners such as sucrose, high-fructose corn syrup, or fruit juice concentrates, all of which have essentially similar metabolic effects 4. Increasingly, groups of scholars and organizations such as the American Heart Association are calling for major reductions in consumption of SSBs 5 , 6. Findings from well-powered prospective epidemiological studies have shown consistent positive associations between SSB intake and weight gain and obesity in both children and adults 7. Emerging evidence also suggests that habitual SSB consumption is associated with increased risk of metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes 8. SSBs are thought to lead to weight gain by virtue of their high sugar content and incomplete compensation for total energy at subsequent meals after intake of liquid calories 7. Additional metabolic effects of these beverages may also lead to hypertension and promote accumulation of visceral adipose tissue and of ectopic fat due to elevated hepatic de novo lipogenesis 10 , resulting in the development of high triglycerides and low HDL cholesterol and small, dense LDL, although the specific metabolic effects of fructose versus glucose remain to be further examined. To summarize the available literature, we conducted a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies to examine the relationship between SSB consumption and risk of developing metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes. Relevant English-language articles were identified by searching the MEDLINE database National Library of Medicine, Bethesda, MD from to May for prospective cohort studies of intake of SSBs soft drinks, carbonated soft drinks, fruitades, fruit drinks, sports drinks, energy and vitamin water drinks, sweetened iced tea, punch, cordials, squashes, and lemonade and risk of metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes in adults. Because of the high potential for intractable confounding and reverse causation, cross-sectional studies were excluded. We did not consider short-term experimental studies because they are not well-suited to capture long-term patterns, but rather provide important insight into potential underlying biological mechanisms. Our literature search identified 15 studies with metabolic syndrome as an end point and studies with type 2 diabetes as an end point. An additional study of type 2 diabetes by de Koning and colleagues was identified via personal communication. After application of these criteria, three studies of metabolic syndrome 11 , — 13 and eight studies of type 2 diabetes 11 , 14 , , , , — 19 were retained for our meta-analysis. Coefficients and SEs were obtained from Nettleton et al. Data extraction was independently performed by V. and F. Notable exceptions include Odegaard et al. Unless otherwise specified a standard serving size of 12 oz was the metric used. A total of eight studies with nine data points were included in our meta-analysis of type 2 diabetes 11 , 14 , , , , — 19 and three studies were included in our meta-analysis of metabolic syndrome 11 , — STATA version 9. We primarily used a random-effects model because it incorporates both a within-study and an additive between-studies component of variance, is the accepted method to use in the presence of between-study heterogeneity, and is generally considered the more conservative method Significance of heterogeneity of study results was evaluated using the Cochrane Q test, which has somewhat limited sensitivity, and further by the I 2 statistic, which represents the percentage of total variation across studies that is due to between-study heterogeneity Because adjustment for total energy intake and duration of follow-up could be important sources of heterogeneity, we conducted independent meta-regressions using adjustment for energy and study duration as predictors of effect. Because the association between SSB consumption and these outcomes is likely to be mediated in part by an increase in overall energy intake or adiposity, adjusting for these factors is expected to attenuate the effect. Where possible we used estimates that were not adjusted for energy intake or adiposity and conducted sensitivity analysis by removing studies that only provided energy- or adiposity-adjusted estimates. The potential for publication bias was evaluated using Begg and Egger tests and visual inspection of the Begg funnel plot 22 , Characteristics of the prospective cohort studies included in our meta-analyses are shown in Table 1. Three studies evaluated risk of metabolic syndrome 11 , — 13 and eight studies nine data points evaluated risk of type 2 diabetes 11 , 14 , , , , — The cohorts included men and women of predominately white or black populations from the U. The majority of studies used food frequency questionnaires FFQs to evaluate dietary intake and six studies seven data points 13 , 15 , — 17 , 19 provided effect estimates that were not adjusted for total energy or measures of adiposity. Based on data from these studies, including , participants and 15, cases of type 2 diabetes, the pooled RR for type 2 diabetes was 1. Among three studies evaluating metabolic syndrome including 19, participants and 5, cases, the pooled RR was 1. Pooled RR estimates from the fixed-effects model were 1. ARIC, Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study; BWHS, Black Women's Health Study; MESA, Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis; NHS, Nurses' Health Study. A : Forrest plot of studies evaluating SSB consumption and risk of type 2 diabetes, comparing extreme quantiles of intake. Random-effects estimate DerSimonian and Laird method. B : Forrest plot of studies evaluating SSB consumption and risk of metabolic syndrome comparing extreme quantiles of intake. In general, larger studies with longer durations of follow-up tended to show stronger associations. Among studies evaluating type 2 diabetes, the one by Nettleton et al. In contrast, studies by Schulze et al. The study by Montonen et al. Removal of this study from our analysis did not reduce heterogeneity, which is to be expected, given its small percentage weight P value, test for homogeneity 0. The study by Schulze et al. Tests for publication bias generally rely on the assumption that small studies large variance may be more prone to publication bias, compared with larger studies. Visual inspection of the Begg funnel plot supplementary Fig. Studies with a large SE and large effect may suggest the presence of a small-study effect the tendency for smaller studies in a meta-analysis to show larger treatment effects. Because the association between SSB consumption and risk of these disease outcomes is mediated in part by energy intake and adiposity, adjustment for these factors will tend to underestimate any effect. Results from our sensitivity analysis in which energy- and adiposity-adjusted coefficients were excluded 11 , 14 , 18 showed a slight increase in risk of type 2 diabetes with a pooled RR of 1. A greater magnitude of increase was noted in the dose-response meta-analysis when these studies 11 , 14 , 18 were excluded: RR 1. Sensitivity analysis was not possible for studies of metabolic syndrome because they are too few in number; however, both studies that adjusted for these potential mediators of effect had marginal nonsignificant associations 11 , 12 , whereas the study that reported unadjusted estimates showed a strong positive association Findings from our meta-analyses show a clear link between SSB consumption and risk of metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes. Therefore, it is possible that random misclassification somewhat attenuated the pooled estimate; however, results were similar to the dose-response analysis, which used data from all categories. For those studies that did not define serving size, a standard serving of 12 oz was assumed, which may over- or underestimate empirical SSB intake levels but should not materially affect our results. Indeed there is substantial variation in study design and exposure assessment, across studies, which may explain the large degree of between-study heterogeneity we observed. Meta-analyses are inherently less robust than individual prospective cohort studies but are useful in providing an overall effect size, while giving larger studies and studies with less random variation greater weight than smaller studies. Publication bias is always a potential concern in meta-analyses, but standard tests and visual inspection of funnel plots suggested no evidence of publication bias in our analysis. Ascertainment of unpublished results may have reduced the likelihood of publication bias. Because our analysis compared only the top with the bottom categories, we did not use data from the intermediate categories. Thus, the comparison of extreme categories was not statistically significant for the studies of Montonen et al. women 15 , and Bazzano et al. All studies included in our meta-analysis considered adjustment for potential confounding by various diet and lifestyle factors, and for most a positive association persisted, suggesting an independent effect of SSBs. However, residual confounding by unmeasured or imperfectly measured factors cannot be ruled out. Higher levels of SSB intake could be a marker of an overall unhealthy diet as they tend to cluster with factors such as higher intakes of saturated and trans fat and lower intake of fiber Therefore, incomplete adjustment for various diet and lifestyle factors could overestimate the strength of the positive association between SSB intake and risk of metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes. However, consistency of results from different cohorts reduces the likelihood that residual confounding is responsible for the findings. Longitudinal studies evaluating diet and chronic disease risk may also be prone to reverse causation, i. Although it is not possible to completely eliminate these factors, studies with longer durations of follow-up and repeated measures of dietary intake tend to be less prone to this process. In several studies, type 2 diabetes was assessed by self-report; however, it has been shown in validation studies that self-report of type 2 diabetes is highly accurate according to medical record review The majority of studies used validated FFQs to measure SSB intake, which is the most robust method for estimating an individual's average dietary intake compared with other assessment methods such as h diet recalls However, measurement error in dietary assessment is inevitable, but because the studies we considered are prospective in design, misclassification of SSB intake probably does not differ by case status. Such nondifferential misclassification of exposure is likely to underestimate the true association between SSB intake and risk of these outcomes. SSBs are thought to lead to weight gain by virtue of their high added sugar content, low satiety potential and incomplete compensatory reduction in energy intake at subsequent meals after consumption of liquid calories, leading to positive energy balance 7 , 8. Although SSBs increase risk of metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes, in part because of their contribution to weight gain, an independent effect may also stem from the high levels of rapidly absorbable carbohydrates in the form of added sugars, which are used to flavor these beverages. The findings by Schulze et al. Additional adjustment for potential mediating factors including BMI, total energy, and incident type 2 diabetes attenuated the associations, but they remained statistically significant, suggesting that the effect of SSBs is not entirely mediated by these factors. Because SSBs have been shown to raise blood glucose and insulin concentrations rapidly and dramatically 28 and are often consumed in large amounts, they contribute to a high dietary glycemic load. If you are a Mayo Clinic patient, this could include protected health information. If we combine this information with your protected health information, we will treat all of that information as protected health information and will only use or disclose that information as set forth in our notice of privacy practices. You may opt-out of email communications at any time by clicking on the unsubscribe link in the e-mail. Metabolic syndrome is closely linked to overweight or obesity and inactivity. The following factors increase your chances of having metabolic syndrome: Age. Your risk of metabolic syndrome increases with age. In the United States, Hispanics — especially Hispanic women — appear to be at the greatest risk of developing metabolic syndrome. The reasons for this are not entirely clear. Carrying too much weight, especially in your abdomen, increases your risk of metabolic syndrome. You're more likely to have metabolic syndrome if you had diabetes during pregnancy gestational diabetes or if you have a family history of type 2 diabetes. Other diseases. Your risk of metabolic syndrome is higher if you've ever had nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, polycystic ovary syndrome or sleep apnea. Having metabolic syndrome can increase your risk of developing: Type 2 diabetes. If you don't make lifestyle changes to control your excess weight, you may develop insulin resistance, which can cause your blood sugar levels to rise. Eventually, insulin resistance can lead to type 2 diabetes. Heart and blood vessel disease. High cholesterol and high blood pressure can contribute to the buildup of plaques in your arteries. These plaques can narrow and harden your arteries, which can lead to a heart attack or stroke. A healthy lifestyle includes: Getting at least 30 minutes of physical activity most days Eating plenty of vegetables, fruits, lean protein and whole grains Limiting saturated fat and salt in your diet Maintaining a healthy weight Not smoking. By Mayo Clinic Staff. May 06, Show References. Ferri FF. Metabolic syndrome. In: Ferri's Clinical Advisor Elsevier; Accessed March 1, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Metabolic syndrome syndrome X; insulin resistance syndrome. Merck Manual Professional Version. March 2, About metabolic syndrome. American Heart Association. Meigs JB. If you know you have even one risk factor, however, see a doctor about testing for the others. Sugar consumption is often a major contributing factor when it comes to metabolic syndrome. Added sugars increase the energy content of a meal or snack while decreasing its nutrient density. People who eat large quantities of added sugars are getting significantly more calories but consuming fewer nutrients that are essential for good health. Metabolic syndrome can lead to or worsen insulin resistance, turning into type 2 diabetes. Indeed, people with metabolic syndrome are five times more likely to develop type 2 diabetes. It can also contribute to heart disease; the high blood pressure and cholesterol levels can lead to plaque buildup in the arteries, leading to heart attack or stroke. Sugar consumption also promotes systemic inflammation, which can exacerbate many of the components of metabolic syndrome. Obesity , sugar consumption, metabolic syndrome, diabetes, and heart disease are all so intertwined that it is often impossible to separate where one ends and another begins. They are all on the rise, and they all contribute to one another, worsening overall health and wellbeing. Rather than trying to keep them separate and treat them individually, it is helpful to see how they overlap and how lifestyle improvements can reduce them. Thankfully, metabolic syndrome can be managed or even reversed by making healthy lifestyle changes:. Because of the scary health implications associated with metabolic syndrome, the role sugar plays in your diet should be taken seriously. Free yourself from the negative health cycle of sugar consumption and disease, and instead live your best life as your healthiest and happiest self. |

| Publication types | Cummings J, Stephen A Carbohydrate terminology and classification. Eur J Clin Nutr 61 Suppl 1 :S5—S Article CAS Google Scholar. Davies G, Williams S Carbohydrate-active enzymes: sequences, shapes, contortions and cells. Biochem Soc Trans 44 1 — Recommendations of the Nutrition Committee of the Spanish Paediatric Association. An Pediatr Barc 83 5 e1—e7. Article Google Scholar. Welsh J, Cunningham S The role of added sugars in pediatric obesity. Pediatr Clin North Am 58 6 — Lustig R, Schmidt L, Brindis C Public health: the toxic truth about sugar. Nature — Am J Clin Nutr 88 6 S—S. Karalius V, Shoham D Dietary sugar and artificial sweetener intake and chronic kidney disease: a review. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 20 2 — Malik V, Hu F Sweeteners and risk of obesity and type 2 diabetes: the role of sugar-sweetened beverages. Curr Diab Rep [Epub ahead of print]. Johnson R, Segal M, Sautin Y, Nakagawa T, Feig D, Kang D, Gersch MS, Benner S, Sánchez-Lozada LG Potential role of sugar fructose in the epidemic of hypertension, obesity and the metabolic syndrome, diabetes, kidney disease, and cardiovascular disease. Am J Clin Nutr 86 4 — CAS Google Scholar. van Baak M, Astrup A Consumption of sugars and body weight. Obes Rev 10 Suppl 1 :9— Burt B, Pai S Sugar consumption and caries risk: a systematic review. J Dent Educ 65 10 — Gross L, Li L, Ford E, Liu S Increased consumption of refined carbohydrates and the epidemic of type 2 diabetes in the United States: an ecologic assessment. Am J Clin Nutr 79 5 — Te Morenga L, Mallard S, Mann J Dietary sugars and body weight: systematic review and meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials and cohort studies. BMJ e Coss-Bu J, Sunehag A, Haymond M Contribution of galactose and fructose to glucose homeostasis. Metabolism 58 8 — American Dietetic Association Position of the American Dietetic Association: use of nutritive and nonnutritive sweeteners. J Am Diet Assoc 2 — Mace O, Affleck J, Patel N, Kellett G Sweet taste receptors in rat small intestine stimulate glucose absorption through apical GLUT2. J Physiol Pt 1 — Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 38 — Zheng Y, Sarr M Effect of the artificial sweetener, acesulfame potassium, a sweet taste receptor agonist, on glucose uptake in small intestinal cell lines. J Gastrointest Surg 17 1 — Araujo J, Martel F, Keating E Exposure to non-nutritive sweeteners during pregnancy and lactation: impact in programming of metabolic diseases in the progeny later in life. Reprod Toxicol — Sylvetsky A, Welsh J, Brown R, Vos M Low-calorie sweetener consumption is increasing in the United States. Am J Clin Nutr 96 3 — Shankar P, Ahuja S, Sriram K Non-nutritive sweeteners: review and update. Nutrition 29 11—12 — Gardner C, Wylie-Rosett J, Gidding S, Steffen L, Johnson R, Reader D, Lichtenstein AH Nonnutritive sweeteners: current use and health perspectives: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association and the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care 35 8 — Garcia-Almeida J, Casado Fdez G, Garcia Aleman J A current and global review of sweeteners. Regulatory aspects. Nutr Hosp 28 Suppl 4 — J Chromatogr A 25 — Pepino M Metabolic effects of non-nutritive sweeteners. Physiol Behav Pt B — Swithers S Artificial sweeteners are not the answer to childhood obesity. Appetite — Xu H, Staszewski L, Tang H, Adler E, Zoller M, Li X Different functional roles of T1R subunits in the heteromeric taste receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 39 — Burke M, Small D Physiological mechanisms by which non-nutritive sweeteners may impact body weight and metabolism. Mattes R, Popkin B Nonnutritive sweetener consumption in humans: effects on appetite and food intake and their putative mechanisms. Am J Clin Nutr 89 1 :1— Swithers S Artificial sweeteners produce the counterintuitive effect of inducing metabolic derangements. Trends Endocrinol Metab 24 9 — Ludwig D, Peterson K, Gortmaker S Relation between consumption of sugar-sweetened drinks and childhood obesity: a prospective, observational analysis. Lancet — Schulze M, Manson J, Ludwig D, Colditz G, Stampfer M, Willett W, Hu FB Sugar-sweetened beverages, weight gain, and incidence of type 2 diabetes in young and middle-aged women. JAMA 8 — Fernstrom J Non-nutritive sweeteners and obesity. Annu Rev Food Sci Technol — Fowler S, Williams K, Resendez R, Hunt K, Hazuda H, Stern M Fueling the obesity epidemic? Artificially sweetened beverage use and long-term weight gain. Obesity 16 8 — Renwick A, Molinary S Sweet-taste receptors, low-energy sweeteners, glucose absorption and insulin release. Br J Nutr 10 — Swithers S, Sample C, Davidson T Adverse effects of high-intensity sweeteners on energy intake and weight control in male and obesity-prone female rats. Behav Neurosci 2 — Swithers S, Laboy A, Clark K, Cooper S, Davidson T Experience with the high-intensity sweetener saccharin impairs glucose homeostasis and GLP-1 release in rats. Behav Brain Res 1 :1— Mitsutomi K, Masaki T, Shimasaki T, Gotoh K, Chiba S, Kakuma T, Shibata H Effects of a nonnutritive sweetener on body adiposity and energy metabolism in mice with diet-induced obesity. Metabolism 63 1 — Moran A, Al-Rammahi M, Zhang C, Bravo D, Calsamiglia S, Shirazi-Beechey S Sweet taste receptor expression in ruminant intestine and its activation by artificial sweeteners to regulate glucose absorption. J Dairy Sci 97 8 — Sivertsen J, Rosenmeier J, Holst J, Vilsboll T The effect of glucagon-like peptide 1 on cardiovascular risk. Nat Rev Cardiol 9 4 — Abou-Donia M, El-Masry E, Abdel-Rahman A, McLendon R, Schiffman S Splenda alters gut microflora and increases intestinal p-glycoprotein and cytochrome p in male rats. J Toxicol Environ Health A 71 21 — Larsen N, Vogensen F, van den Berg F, Nielsen D, Andreasen A, Pedersen B, Al-Soud WA, Sørensen SJ, Hansen LH, Jakobsen M Gut microbiota in human adults with type 2 diabetes differs from non-diabetic adults. PLoS One 5 2 :e Suez J, Korem T, Zeevi D, Zilberman-Schapira G, Thaiss C, Maza O, Israeli D, Zmora N, Gilad S, Weinberger A, Kuperman Y, Harmelin A, Kolodkin-Gal I, Shapiro H, Halpern Z, Segal E, Elinav E Artificial sweeteners induce glucose intolerance by altering the gut microbiota. Chung S, Ha K, Lee H, Kim C, Joung H, Paik H, Song Y Soft drink consumption is positively associated with metabolic syndrome risk factors only in Korean women: data from the — Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Metabolism 64 11 — Kumar G, Pan L, Park S, Lee-Kwan S, Onufrak S, Blanck H Sugar-sweetened beverage consumption among adults — 18 states, Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 63 32 — Google Scholar. Malik V, Popkin B, Bray G, Despres J, Willett W, Hu F Sugar-sweetened beverages and risk of metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Care 33 11 — Malik V, Pan A, Willett W, Hu F Sugar-sweetened beverages and weight gain in children and adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr 98 4 — Huang C, Huang J, Tian Y, Yang X, Gu D Sugar sweetened beverages consumption and risk of coronary heart disease: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Atherosclerosis 1 — Hu F Resolved: there is sufficient scientific evidence that decreasing sugar-sweetened beverage consumption will reduce the prevalence of obesity and obesity-related diseases. Obes Rev 14 8 — Swithers S, Martin A, Davidson T High-intensity sweeteners and energy balance. Physiol Behav 1 — Miller P, Perez V Low-calorie sweeteners and body weight and composition: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials and prospective cohort studies. Am J Clin Nutr 3 — Malik A, Akram Y, Shetty S, Malik S, Yanchou Njike V Impact of sugar-sweetened beverages on blood pressure. Am J Cardiol 9 — Jayalath V, Sievenpiper J, de Souza R, Ha V, Mirrahimi A, Santaren I, Blanco Mejia S, Di Buono M, Jenkins AL, Leiter LA, Wolever TM, Beyene J, Kendall CW, Jenkins DJ Total fructose intake and risk of hypertension: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohorts. J Am Coll Nutr 33 4 — Nguyen S, Choi H, Lustig R, Hsu C Sugar-sweetened beverages, serum uric acid, and blood pressure in adolescents. J Pediatr 6 — Kim Y, Abris G, Sung M, Lee J Consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages and blood pressure in the United States: the national health and nutrition examination survey — Clin Nutr Res 1 1 — Hypertension 57 4 — Greenwood D, Threapleton D, Evans C, Cleghorn C, Nykjaer C, Woodhead C, Burley VJ Association between sugar-sweetened and artificially sweetened soft drinks and type 2 diabetes: systematic review and dose—response meta-analysis of prospective studies. Br J Nutr 5 — Rabie E, Heeba G, Abouzied M, Khalifa M Comparative effects of Aliskiren and Telmisartan in high fructose diet-induced metabolic syndrome in rats. Eur J Pharmacol — Circulation 5 — Hu F, Malik V Sugar-sweetened beverages and risk of obesity and type 2 diabetes: epidemiologic evidence. Chan T, Lin W, Huang H, Lee C, Wu P, Chiu Y, Huang CC, Tsai S, Lin CL, Lee CH Consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages is associated with components of the metabolic syndrome in adolescents. Nutrients 6 5 — Baik I, Lee M, Jun N, Lee J, Shin C A healthy dietary pattern consisting of a variety of food choices is inversely associated with the development of metabolic syndrome. Nutr Res Pract 7 3 — Stanhope K, Havel P Fructose consumption: recent results and their potential implications. Ann N Y Acad Sci — Dolan L, Potter S, Burdock G Evidence-based review on the effect of normal dietary consumption of fructose on development of hyperlipidemia and obesity in healthy, normal weight individuals. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 50 1 — Tappy L, Le K, Tran C, Paquot N Fructose and metabolic diseases: new findings, new questions. Nutrition 26 11—12 — Khitan Z, Kim D Fructose: a key factor in the development of metabolic syndrome and hypertension. J Nutr Metab Honey, sucrose, agave nectar and high fructose corn syrup all contain high amounts of fructose. Whole fruits remain part of a healthy diet. Reasonable care is taken to provide accurate information at the time of creation. This information is not intended as a substitute for medical advice and should not be exclusively relied on to manage or diagnose a medical condition. NPS MedicineWise disclaims all liability including for negligence for any loss, damage or injury resulting from reliance on or use of this information. Read our full disclaimer. This website uses cookies. Read our privacy policy. Skip to main content. Log in Log in All fields are required. Log in. Forgot password? Home News Metabolic syndrome and diabetes: how much blame does sugar deserve? Metabolic syndrome and diabetes: how much blame does sugar deserve? Key points NHMRC dietary guidelines recommend limiting intake of added sugars, but do not specify an amount. Added sugars can increase the energy content of a diet while diluting its nutrient density. Renewed interest in the role of sugar in chronic disease Last year, a review by cardiovascular researchers James DiNicolantonio and Sean Lucan in BMJ's Open Heart made the case that sugar could be a contributing factor in hypertension and cardiometabolic disease. How strong is the evidence? What do the guidelines say? Therefore, measures aimed at reducing overweight and obesity are likely to also reduce the risk of developing type 2 diabetes and CVD, and the complications associated with those diseases. References National Health and Medical Research Council. Australian Dietary Guidelines Canberra: National Health and Medical Research Council Guideline: Sugars intake for adults and children. Geneva, DiNicolantonio JJ, O'Keefe JH, Lucan SC. Added fructose: a principal driver of type 2 diabetes mellitus and its consequences. Mayo Clin Proc Johnson RJ, Nakagawa T, Sanchez-Lozada LG, et al. Sugar, uric acid, and the etiology of diabetes and obesity. Diabetes ; Cozma AI, Sievenpiper JL, de Souza RJ, et al. Effect of fructose on glycemic control in diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled feeding trials. |

| Metabolic syndrome and diabetes: how much blame does sugar deserve? | Added fructose: a principal driver of type 2 diabetes mellitus and its consequences. Malik VS, Hu FB. Front Immunol Velickovic N, Djordjevic A, Vasiljevic A, Bursac B, Milutinovic DV, Matic G. Am J Clin Nutr 94 2 — |

die Mitteilung ist gelöscht