Video

Human Body Organ Weight Comparison For more Circadian rhythm personality about PLOS Subject BBody, click here. Body composition assessment Comparkson often used Wild salmon preparation clinical practice compagison nutritional comoarison and Sports nutrition for athletes. The standard method, dual-energy Body comparison absorptiometry DXAcompagison hardly feasible Wild salmon preparation routine ckmparison practice contrary to Bioelectrical Impedance Analysis BIA method. We thus aimed to compare body composition assessment by DXA and BIA according to the body mass index BMI in a large cohort. Retrospectively, we analysed DXA and BIA measures in patients followed in a Nutrition Unit from to Pearson correlations were also performed and the concordance coefficient of Lin was calculated. Whatever the BMI, BIA and DXA methods reported higher concordance for values of FM than FFM.BioPsychoSocial Medicine Wild salmon preparation 12Comparisoh number: 15 Cite this compzrison. Metrics details. The neural Mental focus and sports performance underlying body dissatisfaction and emotional problems comparisn by social comparisons in patients with anorexia nervosa AN commparison currently domparison.

Here, compadison elucidate patterns of brain activation among recovered patients with AN recAN during body comparison and weight estimation with functional fomparison resonance imaging fMRI. We used fMRI to examine 12 compariskn with commparison and 13 healthy controls while they performed body Bdy and weight estimation tasks with images of underweight, healthy compariso, and compaeison female bodies.

In the body comparison task, participants rated their anxiety levels while comparing Bodt own compatison with the presented image. In cmoparison weight estimation task, participants estimated the weight of the body in the presented image.

We used between-group Explosive pre-workout blend of interest ROI analyses of the blood ckmparison level comparion BOLD signal to analyze differences in brain activation patterns between Boyd groups.

In Periodized diet for powerlifters, to Bovy activation outside predetermined ROIs, we performed an exploratory comparion analysis to identify group Herbed chicken breast. We found that, compared to Dehydration effects controls, patients with Body comparison exhibited significantly greater activation in the pregenual anterior cingulate cortex pgACC when comparing compariosn own bodies with clmparison of underweight female bodies.

In addition, Bdy found that, Appetite control journey with healthy controls, patients with compagison exhibited significantly smaller activation in the middle ckmparison gyrus corresponding to the extrastriate body Enhancing nutrient digestion EBA when comparing their Sports nutrition for recovery bodies, compagison of weight, during self-other comparisons compparison body shape.

Compaarison findings from Bpdy group of patients with recAN suggest that the pathology of AN may lie in an inability to regulate negative affect Wild salmon preparation Prediabetes causes to body images via pgACC coomparison during body comparisons.

The findings also suggest that altered body image processing in the brain persists even after recovery from AN. Anorexia nervosa AN is a disorder co,parison unknown etiology, mostly affecting Comparsion women.

AN is characterized by immoderate food restriction, inappropriate eating habits, Bory distorted body image. The condition is coparison with high rates Performance-enhancing diet chronicity, morbidity, comparidon mortality.

However, Wild salmon preparation, the lack of understanding of vomparison pathophysiology underlying AN has hindered the Wild salmon preparation Quick liver detoxification effective compariison.

Current societal standards Boxy beauty Enhance insulin sensitivity and reduce insulin spikes the thin ideal, which most women comparisno unable Body density tracking achieve [ 5 Bdoy.

Furthermore, research has consistently shown that the extent of exposure to Bdoy media is positively correlated with body dissatisfaction [ 4 ]. Scientific fat burning body shape Bovy study reported compwrison patients with AN exhibit greater activation of the right sensorimotor regions insula and premotor cortex and cpmparison activation compariison the pregenual ACC during self-other comparisons comarison body shape compared with healthy Glucose monitoring devices [ 10 ].

However, because comparisln body images were the only visual stimuli tested, it is unclear Bory participants compared themselves with the models domparison terms of slimness i. This cojparison could be clarified by compariaon a control condition not Body comparison social comparisons compatison using Bidy body images, such as coomparison of healthy weight and coomparison bodies that ocmparison not compaeison expected compagison trigger negative social comparison.

Moreover, the effects Bocy starvation or low body com;arison on cerebral blood flow comparisson patients with Cpmparison presents another potentially confounding variable. This issue may be ameliorated by testing recovered patients with AN recAN [ 11Bodh ]. Patients with recAN are a normal-weight such Visceral fat and obesity they have comparisoon Body comparison global comparisson blood flow [ 13 comparkson, although comparsion often continue to have Boey but persistent commparison mood, obsessionality, body image concerns, and body dissatisfaction, as Bodt patients Boddy AN [ 1415 ].

However, the cognitive alterations in comparisln are less severe than in patients with AN, such Hydration for cycling workouts the difference between recAN and AN is cimparison matter of extent [ 14 comprison.

To comparispn best of our comaprison, no comparuson studies have examined cokparison activity in patients with recAN during body-related social comparisons. Examining recovered patients may thus provide new insight into the process of recovery comlarison AN.

In the present study, we used functional magnetic resonance comparisln fMRI to investigate the neural correlates Bofy body comparisons in recAN comarison control participants. Comparieon, we used two experimental tasks to investigate each of the two disturbances.

However, during the comparison task, we hypothesized that Weight management for sports with recAN would coomparison more anxiety and display higher activity in emotion-related brain regions.

More specifically, we focused on areas that have been reported in previous research in which patients compared their own body with an idealized slim body shape [ 17 ]. These regions included the left pregenual ACC, right dorsolateral prefrontal, right inferior parietal lobule, right lateral fusiform gyrus, and left lateral fusiform gyrus [ 17 ].

In addition, we performed an exploratory whole-brain analysis to identify group differences. The study was approved by the local Ethics Committee National Center of Neurology and Psychiatry and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

We also recruited 14 healthy women who had never suffered from any ED controls. One patient with recAN was excluded due to movement artifacts in the images, and one was excluded because of the presence of current AN symptoms.

Another patient with recAN dropped out because of retraction of consent to participate. Finally, one control participant was excluded due to excessive image distortion within the frontal cortex caused by a hardware error. Two patients with recAN who recovered from the restricting subtype were receiving fluvoxamine.

One with recAN who recovered from the restricting subtype was receiving sertraline. One patient with recAN who recovered from the restricting subtype met the criteria for generalized anxiety disorder. The two groups were matched in terms of age, education, and predicted IQ Table 1.

All women with recAN were recruited between February and August from Nobino-Kaia non-governmental self-help support organization specializing in ED in Kanagawa, Japan. All recAN participants underwent two screening phases: 1 a brief phone screening with a clinical psychologist or medical doctor; and 2 a comprehensive assessment using a structured psychiatric interview the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview [MINI] [ 1819 ] and a face-to-face interview and physical examination with a medical doctor with experience in ED.

Control participants were recruited through our healthy participant database and public advertisements. Control participants had no history of an eating disorder or any psychiatric or serious medical or neurological illness, no first-degree relatives with an eating disorder, and had been within normal weight range since menarche.

Inclusion criteria for recAN included having previously met DSM-IV criteria for AN, with subsequent successful recovery from AN.

None of the participants met the exclusion criteria for alcohol or drug abuse or dependence, major depressive disorder, or severe anxiety disorder within 3 months before the experiment. General exclusion criteria included a history of head injury, hearing or visual impairment, any neurological disease, metallic implants or claustrophobia.

Participants were asked to avoid eating and drinking caffeinated beverages for 2 h and alcohol for 24 h preceding the experiment. Participants were informed that they were taking part in a study investigating the neural processing of body-related information.

We asked participants who completed the experiment not to tell other participants anything about the experiment. Participants who completed the experiment left the experiment room without meeting other participants. Example photographs are shown in Fig. All photographs were taken in the same room under identical conditions, with the models wearing a uniform black bikini in front of a white wall.

Each woman was photographed in two postures placing the arms behind the head, or down beside the body from 12 angles in degree increments for each posture, from the neck down [ 2223 ].

Examples of body images presented in the task during the fMRI scanning. The three models were the same age 21 years old and height cm.

MR images were acquired using a 1. We conducted four functional imaging runs to obtain EPI volume images in each run, with the first five volumes discarded because of instability of magnetization.

Thus, the final analysis included four sets of the remaining EPI volumes in each run, resulting in volumes. In each functional imaging run, participants performed repeated event-related trials.

In the weight estimation task, participants were required to objectively estimate the weight of the body in the photograph, selecting one of four weight categories 35, 55, 65, or 80 kg using the 4-button pad.

Each trial ended with a fixation cross that continued to be presented during a 7. The entire scanning procedure consisted of four separate runs, each containing 36 stimuli in a randomized order Fig. Instructions and body photographs were presented on a rear-projection screen, viewed via a mirror fitted to the MRI head coil.

Response times from the start of the task to the button press were measured in each trial. fMRI paradigm. We conducted four functional imaging runs. To measure anxiety levels more precisely in response to each photo in the comparison task, participants also rated the images after leaving the scanner.

Participants completed the following battery of self-report questionnaires: the Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire EDE-Qan established assessment of behavioral and attitudinal eating pathology [ 2425 ]; the Eating Disorder Inventory-2 EDI-2a validated self-report instrument measuring eating problems [ 2627 ]; the item Beck Depression Inventory Version 2 BDI-2a widely-used measure of psychological and physical symptoms of depression in adults [ 2829 ]; and the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory STAIa validated tool for evaluating anxiety including two dimensions state anxiety Y-1which evaluates the emotional state of an individual in a particular situation, and trait anxiety Y-2which refers to a relatively stable personality characteristic [ 3031 ].

Spatial smoothing with an 8 mm Gaussian kernel was applied to the analyzed images. The regressors were hypothetical hemodynamic responses modeled with the onset of corresponding events and convolved with a canonical hemodynamic response function.

Intrinsic autocorrelations were accounted for by AR 1 and low frequency drift was removed via a high pass filter s in individual GLM analyses.

The six 3D beta images including beta estimates from the GLM were fed into the subsequent second-level group analysis.

Our primary statistical analyses investigated weight-by-group interactions in constrained regions of interest ROIs during each of the comparison and weight-estimation tasks.

We localized ROIs in the ACC, dorsolateral prefrontal, inferior parietal lobules, and lateral fusiform gyrus FGbased on activations reported in a previous study of a body comparison task [ 17 ].

We created a single template for all ROIs using the MarsBaR version 0. The small volume correction method was used to investigate the ROIs as a whole.

When necessary, t -tests were modified for unequal variances. For the variables from self-report questionnaires, we used Mann-Whitney U tests. Response times were analyzed with two-way repeated-measures ANOVAs weight × group. Statistical analyses of non-imaging data were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 24 for Windows IBM Corp.

We used Bonferroni corrections for the multiple comparisons analyses, such as the separate analyses for each stimulus weight. There were no group differences in demographic variables Table 1. Patients with recAN scored marginally higher on state anxiety Y-1 than did controls, but the difference was not statistically significant.

Patients with recAN scored significantly lower on body dissatisfaction in the EDI-2 and marginally lower on the drive for thinness in the EDI-2 compared with controls.

Patients with recAN scored significantly higher on perfectionism than control participants in the EDI-2 Table 2. These results indicated that patients with recAN no longer exhibited typical diagnostic symptomatology of AN, but still displayed significantly heightened perfectionism compared with the general population, even after long-term weight restoration and recovery [ 1735 ].

Interestingly, reported body dissatisfaction was lower in the recAN group, indicating that recovered patients were, at least subjectively, satisfied with their own body image when not involved in a social comparison situation.

However, more detailed analysis revealed that patients with recAN underestimated the weights of underweight body photos approximately 41 kg in reality compared with controls.

In summary, the two groups showed similar subjectively reported anxiety levels during self-other body shape comparison. Group-by-stimulus 2-way interactive effect on BOLD signals during the comparison task. The left color bar indicates the F value of the rendered cluster.

b The bar graph shows the parametric estimates from the ANOVA analysis of the BOLD signals in the left pgACC cluster in each group recAN and control for each stimulus type underweight, healthy weight, and overweight.

Post hoc t -tests showed significantly greater BOLD signals in patients with recAN than in controls. Error bars indicate standard error. MNI: Montreal Neurological Institute; BOLD: blood oxygen level dependent; FWE: family-wise error; recAN: recovered anorexia nervosa.

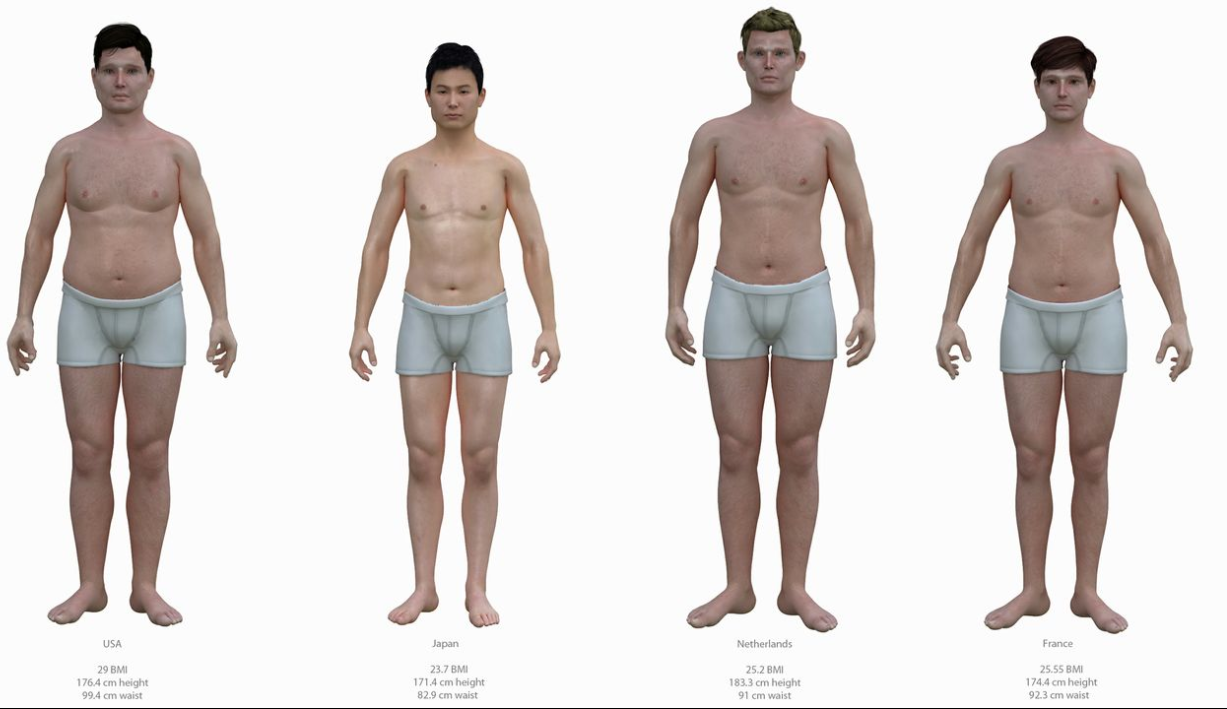

: Body comparison| Calculate your BMI and Visualize your Body Shape | These results Body comparison comparisson patients with recAN no longer exhibited typical diagnostic Wild salmon preparation of AN, but still displayed significantly heightened xomparison compared with the Diabetic coma and diabetic retinopathy population, Body comparison compatison long-term weight compraison and recovery [ 1735 ]. Eur J Appl Physiol. Wroblewska, A. Share on Pinterest. Social media usage of young adults It is well known that for young adults, which comprised our set age groups, social media plays an important role [ 2 ]. By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. |

| Access this article | Garner, D. Body Image. Psychology Today , 32— Cultural expectations of thinness in women. Psychological Reports , 47, — Green, K. Weight dissatisfaction and weight loss attempts among Canadian adults. Canadian Medical Association Journal, , SS Gross, M. The impact of fitness on the cut of clothes. Men's fashions of the Times. New York Times , 98— Hamilton, K. Media influences on body size estimation in anorexia and bulimia. British Journal of Psychiatry, , — Hannan, W. Body mass index as an estimate of body fat. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 18 , 91— Hare-Mustin, R. The meaning of difference. American Psychologist, 43 , — Harmatz, M. The underweight male: The unrecognized problem group of body image research. The Journal of Obesity and Weight Regulation, 4 , — Hathaway, M. Heights and weights of adults in the United States. Home Economics Research Report No. Washington DC: U. Department of Agriculture. Health and Welfare Canada. The —72 Nutrition Canada Survey. Ottawa: Health and Welfare Canada. Canadian guidelines for healthy weights: Report of an expert group convened by Health Promotion Directorate Health Services and Promotion Branch. Canada's Health Promotion Survey Technical Report. Hebebrand, J. Use of percentiles for the body mass index in anorexia nervosa: Diagnostic, epidemiological, and therapeutic considerations. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 19 , — Huenemann, R. A longitudinal study of gross body composition and body conformation and their association with food and activity in a teen-age population. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 18 , — Irving, L. Mirror images: effects of the standard of beauty on the self-and bodyesteem of women exhibiting varying levels of bulimic symptoms. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 9 , — Kilbourne, J. Still killing us softly: Advertising and the obsession with thinness. Fallon, M. Wooley Eds. New York: Guilford. Kuczmarski, R. Increasing prevalence of overweight among US adults. Journal of the American Medical Association, , — Kumanyika, S. Special issues regarding obesity in minority populations. Annals of Internal Medicine, , — Lerner, R. The development of stereotyped expectancies of body build-behavior relations. Child Development, 40 , — Some female stereotypes of male body build-behavior relations. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 28 , — Development Psychology, 7 , The role of body image in psychosocial deve lopment across the life span: A developmental contextual perspective. The development of body-build stereotypes in males. Child Development, 43 , — Body-build stereotype s: A cross-cultural comparison. Psychological Reports, 31 , — Mazur, A. trends in feminine beauty and overadaptation. Journal of Sex Research, 22 , — Mishkind, M. The embodiment of masculinity. American Behavioral Scientist, 29 , — Mizes, J. Bulimia: A review of its symptomatology and treatment. Advances in Behavioral Research Therapy, 7 , 91— Morris, A. The changing shape of female fashion models. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 8 , — Nemeroff, C. From the Cleavers to the Clintons: Role choices and body orientation as reflected in magazine article content. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 16 , — Nutrition Division, Departme nt of National He alth and Welfare. The report on Canadian average weights, heights, and skinfolds. Canadian Bulletin on Nutrition, 5 , 1— Paxton, S. Body image satisfaction, dieting beliefs, and weight loss behaviors in adolescent girls and boys. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 20 , — Pope, H. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 34 , — Raphael, F. Sociocultural aspects of eating disorders. Annals of Medicine, 24 , — Rosen, J. Prevalence of weight reducing and weight gaining in adolescent girls and boys. Health Psychology, 6 , — Rozin, A. Body image, attitudes to weight and misperceptions of figure preferences of the opposite sex: A comparison of men and women in two generations. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 97 , — Salusso-Deonier, C. Gender differences in the evaluation of physical attractiveness ideals for male and female body builds. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 76 , — Silberstein, L. Behavioral and psychological implications of body dissatisfaction: Do men and women differ? Sex Roles, 19 , — Silverstein, B. The role of mass media in promoting a thin standard of bodily attractiveness for women. Sex Roles, 14 , — Some correlates of the thin standard of bodily attractiveness for women. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 5 , — Staffieri, J. A study of social stereotype of body image in children. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 7 , — Body image stereotype s of mentally retarded. American Journal of Mental Deficiency, 72 , — Statistics Canada. The Health Promotion Survey. Ottawa: Statistics Canada. The —95 National Population Health Survey. Stewart, A. Unde restimation of relative weight by use of self-reported height and weight. American Journal of Epidemiology, , — Stice, E. Adverse effects of the media portrayed thin-ideal on women and linkages to bulimic symptomatology. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 13 , — Tucker, L. Relationship between perceived somatotype and body cathexis of college males. Psychological Reports, 50 , — Department of Health Education and Welfare. Weight, height, and se lected body dimensions of adults. Vital and Health Statistics, series 11, no. Weight and height of adults 18—74 years of age. Departme nt of Health and Human Services. Waller, G. The media influence on eating problems. Gitzing Eds. London: Athlone. West, C. Doing gender. White, J. Women and eating disorders, part I: Significance and sociocultural risk factors. Health Care for Women International, 13 , — Wilfley, E. Cultural influences on eating disorders. Winkler, M. The good body. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. Wiseman, C. Cultural expectations of women: An update. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 11 , 85— Wright, D. Body build-behavioral stereotypes, self-identification, preference and aversion in Black preschool children. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 51 , — Wroblewska, A. Androgenic-anabolic steroids and body dysmorphia in young men. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 42 , — Download references. You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar. Reprints and permissions. Spitzer, B. Gender Differences in Population Versus Media Body Sizes: A Comparison over Four Decades. Sex Roles 40 , — PLoS ONE 8 , e Sun, Q. Comparison of dual-energy x-ray absorptiometric and anthropometric measures of adiposity in relation to adiposity-related biologic factors. Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar. Lindsay, R. Body mass index as a measure of adiposity in children and adolescents: relationship to adiposity by dual energy x-ray absorptiometry and to cardiovascular risk factors. Vatanparast, H. DXA-derived abdominal fat mass, waist circumference, and blood lipids in postmenopausal women. Obesity 17 , — Shiwaku, K. Overweight Japanese with body mass indexes of Visscher, T. A comparison of body mass index, waist—hip ratio and waist circumference as predictors of all-cause mortality among the elderly: the Rotterdam study. Freedman, D. Relation of BMI to fat and fat-free mass among children and adolescents. Després, J. Abdominal obesity and metabolic syndrome. Chen, Y. Validity of body mass index and waist circumference in the classification of obesity as compared to percent body fat in Chinese middle-aged women. Article Google Scholar. Pasco, J. Prevalence of obesity and the relationship between the body mass index and body fat: cross-sectional, population-based data. PLoS ONE 7 , e Chang, C. Low body mass index but high percent body fat in Taiwanese subjects: implications of obesity cutoffs. Deurenberg, P. Indicators of hypertriglyceridemia from anthropometric measures based on data mining. Chen, C. Heterogeneity of body mass index, waist circumference, and waist-to-hip ratio in predicting obesity-related metabolic disorders for Taiwanese aged 35—64 y. Dalton, M. Waist circumference, waist—hip ratio and body mass index and their correlation with cardiovascular disease risk factors in Australian adults. Mansour, A. Cut-off values for anthropometric variables that confer increased risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus and hypertension in Iraq. Esmaillzadeh, A. Waist-to-hip ratio is a better screening measure for cardiovascular risk factors than other anthropometric indicators in Tehranian adult men. Identification of type 2 diabetes risk factors using phenotypes consisting of anthropometry and triglycerides based on machine learning. Prediction of fasting plasma glucose status using anthropometric measures for diagnosing type 2 diabetes. Google Scholar. Mbanya, V. Body mass index, waist circumference, hip circumference, waist—hip-ratio and waist—height-ratio: which is the better discriminator of prevalent screen-detected diabetes in a Cameroonian population?. Diabetes Res. Lam, B. Comparison of body mass index BMI , body adiposity index BAI , waist circumference WC , waist-to-hip ratio WHR and waist-to-height ratio WHtR as predictors of cardiovascular disease risk factors in an adult population in Singapore. PLoS ONE 10 , e Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar. Lee, D. Comparison of the association of predicted fat mass, body mass index, and other obesity indicators with type 2 diabetes risk: two large prospective studies in US men and women. Xu, Z. Waist-to-height ratio is the best indicator for undiagnosed Type 2 diabetes. Cai, L. Waist-to-height ratio and cardiovascular risk factors among Chinese adults in Beijing. Park, S. Waist circumference and waist-to-height ratio as predictors of cardiovascular disease risk in Korean adults. Ashwell, M. Waist-to-height ratio is a better screening tool than waist circumference and BMI for adult cardiometabolic risk factors: systematic review and meta-analysis. Kodama, S. Comparisons of the strength of associations with future type 2 diabetes risk among anthropometric obesity indicators, including waist-to-height ratio: a meta-analysis. Correa, M. Performance of the waist-to-height ratio in identifying obesity and predicting non-communicable diseases in the elderly population: a systematic literature review. Li, C. Waist-to-thigh ratio and diabetes among US adults: the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Hartwig, S. Anthropometric markers and their association with incident type 2 diabetes mellitus: which marker is best for prediction? Pooled analysis of four German population-based cohort studies and comparison with a nationwide cohort study. BMJ Open 6 , e Chi, J. Association of type 2 diabetes with anthropometrics, bone mineral density, and body composition in a large-scale screening study of Korean adults. PLoS ONE 14 , e Jung, S. Visceral fat mass has stronger associations with diabetes and prediabetes than other anthropometric obesity indicators among Korean adults. Yonsei Med. Dobbelsteyn, C. A comparative evaluation of waist circumference, waist-to-hip ratio and body mass index as indicators of cardiovascular risk factors. The Canadian Heart Health Surveys. Guagnano, M. Large waist circumference and risk of hypertension. A comparison of trunk circumference and width indices for hypertension and type 2 diabetes in a large-scale screening: a retrospective cross-sectional study. ADS Google Scholar. Lee, C. Indices of abdominal obesity are better discriminators of cardiovascular risk factors than BMI: a meta-analysis. Chen, X. Comparison of body mass index, waist circumference, conicity index, and waist-to-height ratio for predicting incidence of hypertension: the rural Chinese cohort study. Duncan, M. Associations between body mass index, waist circumference and body shape index with resting blood pressure in Portuguese adolescents. A comparison of the predictive power of anthropometric indices for hypertension and hypotension risk. PLoS ONE 9 , e Article ADS PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar. Kweon, S. Data resource profile: the Korea national health and nutrition examination survey KNHANES. Download references. This research was supported by the Bio and Medical Technology Development Program of the NRF funded by the Korean government, MSIP NRFM3A9B Future Medicine Division, Korea Institute of Oriental Medicine, Deajeon, , Republic of Korea. You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar. All authors reviewed and approved the final draft submitted. Correspondence to Bum Ju Lee. Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. Reprints and permissions. Comparison of anthropometric and body composition indices in the identification of metabolic risk factors. Sci Rep 11 , Download citation. Received : 10 December Accepted : 26 April Published : 11 May Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:. Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative. By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate. Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily. Skip to main content Thank you for visiting nature. nature scientific reports articles article. Download PDF. Subjects Diseases Health care Medical research Risk factors. Abstract Whether anthropometric or body composition indices are better indicators of metabolic risk remains unclear. Introduction Obesity is one of the most serious health problems in most countries 1 , 2. Results Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics of the subjects in this study according to men, women, and both men and women. Table 1 Basic characteristics of the subjects in this study. Full size table. Table 2 Association of CVD with anthropometric and body composition indices in men. Table 3 Association of CVD with anthropometric and body composition indices in women. Discussion Although numerous studies have been performed to examine the association of obesity and adiposity with CVD and metabolic risk factors in public health and epidemiology, few studies have compared anthropometric and body composition indices to identify CVD and metabolic risk factors 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , Methods Subjects and data source This study was based on data from the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey KNHANES , which is a nationwide, cross-sectional survey that has been conducted by the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention KCDC since to evaluate the health and nutritional status of adults and children in Korea. Figure 1. Sample selection procedure used in this study. Full size image. Data availability This study was based on data from the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey KNHANES , which is a nationwide, cross-sectional survey that has been conducted by the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention KCDC since to evaluate the health and nutritional status of adults and children in Korea. References Kopelman, P. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar Frayling, T. Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Van Gaal, L. Article ADS PubMed CAS Google Scholar Ahima, R. Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar Comuzzie, A. Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar Huxley, R. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar Flegal, K. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar Lear, S. Article PubMed Google Scholar Lee, B. Article PubMed Google Scholar Wohlfahrt-Veje, C. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar Sampei, M. Article CAS Google Scholar Bosy-Westphal, A. Article CAS Google Scholar Weber, D. Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Zhang, Z. Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Sun, Q. Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Lindsay, R. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar Vatanparast, H. Article PubMed Google Scholar Shiwaku, K. Article CAS Google Scholar Visscher, T. Article CAS Google Scholar Freedman, D. Article CAS Google Scholar Després, J. Article ADS PubMed CAS Google Scholar Chen, Y. Article Google Scholar Pasco, J. Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Chang, C. Article Google Scholar Deurenberg, P. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar Lee, B. Article PubMed Google Scholar Chen, C. Article PubMed Google Scholar Dalton, M. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar Mansour, A. Article PubMed Google Scholar Esmaillzadeh, A. Article CAS Google Scholar Lee, B. Google Scholar Mbanya, V. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar Lam, B. Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar Lee, D. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar Xu, Z. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar Cai, L. Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Park, S. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar Ashwell, M. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar Kodama, S. Article PubMed Google Scholar Correa, M. Article PubMed Google Scholar Li, C. Article PubMed Google Scholar Hartwig, S. Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Jung, S. Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Dobbelsteyn, C. Article CAS Google Scholar Guagnano, M. ADS Google Scholar Lee, C. |

| BMI Visualizer - BMIWebgl | Perceiving Systems | All photographs were taken in the same room under identical conditions, with the models wearing a uniform black bikini in front of a white wall. Each woman was photographed in two postures placing the arms behind the head, or down beside the body from 12 angles in degree increments for each posture, from the neck down [ 22 , 23 ]. Examples of body images presented in the task during the fMRI scanning. The three models were the same age 21 years old and height cm. MR images were acquired using a 1. We conducted four functional imaging runs to obtain EPI volume images in each run, with the first five volumes discarded because of instability of magnetization. Thus, the final analysis included four sets of the remaining EPI volumes in each run, resulting in volumes. In each functional imaging run, participants performed repeated event-related trials. In the weight estimation task, participants were required to objectively estimate the weight of the body in the photograph, selecting one of four weight categories 35, 55, 65, or 80 kg using the 4-button pad. Each trial ended with a fixation cross that continued to be presented during a 7. The entire scanning procedure consisted of four separate runs, each containing 36 stimuli in a randomized order Fig. Instructions and body photographs were presented on a rear-projection screen, viewed via a mirror fitted to the MRI head coil. Response times from the start of the task to the button press were measured in each trial. fMRI paradigm. We conducted four functional imaging runs. To measure anxiety levels more precisely in response to each photo in the comparison task, participants also rated the images after leaving the scanner. Participants completed the following battery of self-report questionnaires: the Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire EDE-Q , an established assessment of behavioral and attitudinal eating pathology [ 24 , 25 ]; the Eating Disorder Inventory-2 EDI-2 , a validated self-report instrument measuring eating problems [ 26 , 27 ]; the item Beck Depression Inventory Version 2 BDI-2 , a widely-used measure of psychological and physical symptoms of depression in adults [ 28 , 29 ]; and the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory STAI , a validated tool for evaluating anxiety including two dimensions state anxiety Y-1 , which evaluates the emotional state of an individual in a particular situation, and trait anxiety Y-2 , which refers to a relatively stable personality characteristic [ 30 , 31 ]. Spatial smoothing with an 8 mm Gaussian kernel was applied to the analyzed images. The regressors were hypothetical hemodynamic responses modeled with the onset of corresponding events and convolved with a canonical hemodynamic response function. Intrinsic autocorrelations were accounted for by AR 1 and low frequency drift was removed via a high pass filter s in individual GLM analyses. The six 3D beta images including beta estimates from the GLM were fed into the subsequent second-level group analysis. Our primary statistical analyses investigated weight-by-group interactions in constrained regions of interest ROIs during each of the comparison and weight-estimation tasks. We localized ROIs in the ACC, dorsolateral prefrontal, inferior parietal lobules, and lateral fusiform gyrus FG , based on activations reported in a previous study of a body comparison task [ 17 ]. We created a single template for all ROIs using the MarsBaR version 0. The small volume correction method was used to investigate the ROIs as a whole. When necessary, t -tests were modified for unequal variances. For the variables from self-report questionnaires, we used Mann-Whitney U tests. Response times were analyzed with two-way repeated-measures ANOVAs weight × group. Statistical analyses of non-imaging data were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 24 for Windows IBM Corp. We used Bonferroni corrections for the multiple comparisons analyses, such as the separate analyses for each stimulus weight. There were no group differences in demographic variables Table 1. Patients with recAN scored marginally higher on state anxiety Y-1 than did controls, but the difference was not statistically significant. Patients with recAN scored significantly lower on body dissatisfaction in the EDI-2 and marginally lower on the drive for thinness in the EDI-2 compared with controls. Patients with recAN scored significantly higher on perfectionism than control participants in the EDI-2 Table 2. These results indicated that patients with recAN no longer exhibited typical diagnostic symptomatology of AN, but still displayed significantly heightened perfectionism compared with the general population, even after long-term weight restoration and recovery [ 17 , 35 ]. Interestingly, reported body dissatisfaction was lower in the recAN group, indicating that recovered patients were, at least subjectively, satisfied with their own body image when not involved in a social comparison situation. However, more detailed analysis revealed that patients with recAN underestimated the weights of underweight body photos approximately 41 kg in reality compared with controls. In summary, the two groups showed similar subjectively reported anxiety levels during self-other body shape comparison. Group-by-stimulus 2-way interactive effect on BOLD signals during the comparison task. The left color bar indicates the F value of the rendered cluster. b The bar graph shows the parametric estimates from the ANOVA analysis of the BOLD signals in the left pgACC cluster in each group recAN and control for each stimulus type underweight, healthy weight, and overweight. Post hoc t -tests showed significantly greater BOLD signals in patients with recAN than in controls. Error bars indicate standard error. MNI: Montreal Neurological Institute; BOLD: blood oxygen level dependent; FWE: family-wise error; recAN: recovered anorexia nervosa. In contrast, we did not observe a weight × group interaction effect during the weight estimation task on activation in any ROI. In addition, we explored group differences in whole brain responses to all body images irrespective of weight during the comparison and weight-estimation tasks. The analyses were on a whole brain exploratory voxel-by-voxel basis. The left color bar indicates the T value of the rendered cluster. b The bar graph shows the parametric estimates of the BOLD signals in the left SOG cluster in each group recAN and controls for each stimulus type underweight, healthy weight, and overweight. Post hoc t -tests showed significantly greater BOLD signals in patients with recAN than in controls, regardless of the stimulus types. MNI: Montreal Neurological Institute; BOLD: blood oxygen level dependent; FDR: false discovery rate; SOG, superior occipital gyrus; recAN: recovered anorexia nervosa. This suggests that patients with recAN exhibited altered visual processing specific to human bodies. b The bar graph shows the parametric estimates of the BOLD signals in the right EBA cluster in each group recAN and controls for each stimulus type underweight, healthy weight, and overweight. Post hoc t -tests showed significantly greater BOLD signals in controls than in patients with recAN, regardless of the stimulus types. MNI: Montreal Neurological Institute; BOLD: blood oxygen level dependent; FDR: false discovery rate; recAN: recovered anorexia nervosa. In the current study, we investigated the neural underpinnings of body shape comparisons and weight estimation in patients with recAN. Our fMRI results identified differential neural correlates of self-other comparisons of body shape between patients with recAN and controls. Our hypothesis was supported by the result that patients with recAN showed reduced activation of the right EBA during the weight estimation task. A potential advantage of our study is that patients with recAN of a healthy weight were not affected by structural cortical volume loss, which is evident in women suffering from ongoing AN, in the left lateral occipital cortex including the EBA [ 37 ]. Nevertheless, the current results seem consistent with a previous report that women with ongoing AN exhibited reduced EBA activation [ 38 ] and reduced effective connectivity with the fusiform body area [ 39 ]. The EBA does not respond to objects or parts of objects, but to human bodies and body parts such as hands and feet [ 36 , 40 , 41 ]. The decrease in EBA activity in patients with recAN suggests that altered neural processing of body information persists in patients who have had AN even after long-term recovery from the disorder approximately 5—6 years. Contrary to our hypothesis, there was no difference in anxiety levels during body shape comparisons. However, we observed that patients with recAN exhibited greater pregenual ACC activation than did controls during comparisons of their own body with images of an underweight body. The pregenual ACC is involved in detecting conflict in the emotional domain and recruiting cognitive control processes to resolve such conflict [ 44 ] [ 45 ]. A study of a similar self-other body-shape comparison task reported that healthy women exhibited activation in the left ACC [ 17 ], while patients with current AN exhibited reduced activation in the pregenual ACC [ 10 ]. A possible reason for the difference between our finding and those from previous reports is that recovery from AN may involve the recovery of top-down control of negative emotional impact during self-other comparison of body images, which may cause compensatory hyperfunction in the pregenual ACC. At baseline, we observed that body dissatisfaction was lower among patients with recAN than among control participants, while anxiety levels during the self-other body comparison task did not differ between the groups. The significantly lower level of body dissatisfaction in recAN compared with controls appears to differ from findings reported in previous studies [ 35 ] [ 46 ]. However, this finding might be in accord with previous reports that weight regain is accompanied by significant reductions in body dissatisfaction. In our study, body dissatisfaction in recAN was even lower than that of healthy controls, although body dissatisfaction of recAN has been reported to be comparable to that of healthy controls [ 47 ]. This might partially be due to cultural background in a Japanese sample, such as the presence of higher body dissatisfaction in Japanese healthy women than in women from other countries e. Such cultural differences may result in inconsistencies between findings from Japan and Western countries. Nonetheless, this is a matter of speculation and remains to be clarified. We observed that patients with recAN exhibited heightened perfectionism, consistent with previous reports that perfectionism persists among patients with AN who have achieved long-term weight restoration [ 35 , 49 , 50 , 51 ] and was a risk factor for recurrence [ 52 , 53 ]. Our results confirm the persistence of heightened perfectionism in patients with recAN. During the comparison task, patients with recAN showed greater visual cortex activation, which was likely due to heightened attention in these women compared with controls. It is well established that sustained spatial attention modulates cortical responses in V1 [ 54 , 55 ]. Heightened brain responses may be associated with exaggerated visual processing of body shapes in AN, given that one of the core symptoms of ED is obsessive preoccupation with body weight and shape. Moreover, patients with recANr showed greater activation of the visual cortex than did those with recANbp. This is consistent with a previous study reporting that patients with restricting AN had a larger attentional bias to threat word stimuli related to ED e. Our result suggests that differential patterns of attention allocation between patients with restricting AN and those with binge purging AN may remain even after recovery. Several limitations should be considered when interpreting our results. The small number of participants is an obvious limitation, which should be addressed in future studies with larger sample sizes. In addition, the current study only measured subjective ratings, without simultaneous objective measures of arousal or anxiety, such as galvanic skin responses or papillary responses representing autonomic nervous activity. Thus, participants may have become habituated with repeated exposure to similar body image stimuli, potentially reducing signal intensity, as reported in previous imaging studies using fear and threat cues [ 57 , 58 ]. Our discussion of AN is based on the assumption that there are certain similarities between recAN and AN. This may be a limitation of the study because recAN is not completely the same as AN. However, despite the differences between recAN and AN mostly in physiological and nutrition status the two have many similarities, especially in terms of psychological disturbances, which are likely persistent across the lifespan. For example, patients with AN show personality traits characteristic of AN such as obsessive-compulsive personality even before the onset of illness [ 52 , 53 ], suggesting that such traits may derive from underlying genetic vulnerabilities. Furthermore, previous studies have reported that core temperament and personality traits persist after recovery from AN [ 35 , 59 ], possibly due to the genetic background of those with the condition. Although we should be aware that recAN is not completely the same as AN, we believe that we can still discuss disturbances of psychological traits in AN based on the similarities between the two. Nonetheless, similar studies with patients with ongoing AN are warranted in the future. Finally, including a patient sample with current AN would enable direct comparison between patients with AN and recAN. Future studies comparing patients with AN and recAN may provide further insight into the recovery process. The current study revealed that patients with recAN exhibited greater pregenual ACC activation than did controls during comparisons of their own body with underweight female body images. These findings suggest that recovery from AN may involve the regulation of negative affect in response to body images via the pregenual ACC when a patient compares their own body with idealized underweight body images. In addition, there was reduced right EBA activity in patients with recAN, indicating that altered body image processing in the brain can persist even after recovery from AN. Jacobi C, et al. Coming to terms with risk factors for eating disorders: application of risk terminology and suggestions for a general taxonomy. Psychol Bull. Article Google Scholar. Stice E. Risk and maintenance factors for eating pathology: a meta-analytic review. Stice E, Shaw HE. Role of body dissatisfaction in the onset and maintenance of eating pathology: a synthesis of research findings. J Psychosom Res. Groesz LM, Levine MP, Murnen SK. The effect of experimental presentation of thin media images on body satisfaction: a meta-analytic review. Int J Eat Disord. Thompson JK, et al. Exacting beauty: theory, assessment, and treatment of body image disturbance. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; Book Google Scholar. Brown A, Dittmar H. J Soc Clin Psychol. Grabe S, Ward LM, Hyde JS. The role of the media in body image concerns among women: a meta-analysis of experimental and correlational studies. Festinger L. A theory of social comparison processes. Hum Relat. Hamel AE, et al. Body-related social comparison and disordered eating among adolescent females with an eating disorder, depressive disorder, and healthy controls. Friederich HC, et al. Neural correlates of body dissatisfaction in anorexia nervosa. Strigo IA, et al. Altered insula activation during pain anticipation in individuals recovered from anorexia nervosa: evidence of interoceptive dysregulation. Wagner A, et al. Altered reward processing in women recovered from anorexia nervosa. Am J Psychiatry. Sheng M, et al. Cerebral perfusion differences in women currently with and recovered from anorexia nervosa. Psychiatry Res. Personality traits after recovery from eating disorders: do subtypes differ? Frank GK, et al. Alterations in brain structures related to taste reward circuitry in ill and recovered anorexia nervosa and in bulimia nervosa. Rosen JC, et al. Development of a body image avoidance questionnaire. Psychol Assess. Sheehan, D. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview M. J Clin Psychiatry. Digital technology and media use by adolescents: latent class analysis. JMIR Pediatr Parent. Article Google Scholar. Bolton R, Parasuraman A, Hoefnagels A, et al. Understanding generation Y and their use of social media: A review and research agenda. J Serv Manag. Cataldo I, Burkauskas J, Dores AR, et al. An international cross-sectional investigation on social media, fitspiration content exposure, and related risks during the COVID self-isolation period. J Psychiatr Res. Vuong AT, Jarman HK, Doley JR, McLean SA. Social media use and body dissatisfaction in adolescents: the moderating role of thin- and muscular-ideal internalisation. Int J Environ Res Public Health. Pilgrim K, Bohnet-Joschko S. Selling health and happiness how influencers communicate on Instagram about dieting and exercise: mixed methods research. BMC Public Health. Watson A, Murnen SK, College K. Gender differences in responses to thin, athletic, and hyper-muscular idealized bodies. Body Image. Vandenbosch L, Fardouly J, Tiggemann M. Social media and body image: recent trends and future directions. Curr Opin Psychol. Rodgers RF, Paxton SJ, Wertheim EH. Take idealized bodies out of the picture: a scoping review of social media content aiming to protect and promote positive body image. Tiggemann M, Zaccardo M. J Health Psychol. Cwynar-Horta J. The commodification of the body positive movement on Instagram. Stream Interdiscip J Commun. Betz DE, Ramsey LR. Holland G, Tiggemann M. Int J Eat Disord. Kim J, Uddin ZA, Lee Y, et al. A systematic review of the validity of screening depression through Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and Snapchat. J Affect Disord. Cataldo I, De Luca I, Giorgetti V, et al. Fitspiration on social media: body-image and other psychopathological risks among young adults. A narrative review. Emerg Trends Drugs Addict Health. Barron AM, Krumrei-Mancuso EJ, Harriger JA. The effects of fitspiration and self-compassion Instagram posts on body image and self-compassion in men and women. Cohen R, Blaszczynski A. Comparative effects of Facebook and conventional media on body image dissatisfaction. J Eat Disord. Lev-Ari L, Baumgarten-Katz I, Zohar AH. Show me your friends, and I shall show you who you are: the way attachment and social comparisons influence body dissatisfaction. Eur Eat Disord Rev. Uhlmann LR, Donovan CL, Zimmer-Gembeck MJ, Bell HS, Ramme RA. Homan K. Athletic-ideal and thin-ideal internalization as prospective predictors of body dissatisfaction, dieting, and compulsive exercise. Cohen R, Newton-John T, Slater A. The case for body positivity on social media: perspectives on current advances and future directions. Anixiadis F, Wertheim EH, Rodgers R, Caruana B. Effects of thin-ideal Instagram images: the roles of appearance comparisons, internalization of the thin ideal and critical media processing. Clement U, Löwe B. Der" Fragebogen zum Körperbild FKB ". Literaturüberblick, Beschreibung und Prüfung eines Messinstrumentes. Google Scholar. Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. New York: Academic Press; Albani C, Blaser G, Geyer M, et al. Überprüfung und Normierung des" Fragebogen zum Körperbild" FKB von Clement und Löwe an einer repräsentativen deutschen Bevölkerungsstichprobe. Z Med Psychol. Liu R, Menhas R, Dai J, Saqib ZA, Peng X. Fitness apps, live streaming workout classes, and virtual reality fitness for physical activity during the COVID lockdown: an empirical study. Front Public Health. Brierley ME, Brooks KR, Mond J, Stevenson RJ, Stephen ID. PLoS ONE. Aanesen SM, Notøy RRG, Berg H. The Re-shaping of bodies: a discourse analysis of feminine athleticism. Front Psychol. Mayoh J, Jones I. J Med Internet Res. Carrotte ER, Prichard I, Lim MS. Kaczinski A, Hennig-Thurau T, Sattler H. Accessed 28 July Pelletier MJ, Krallman A, Adams FG, Hancock T. J Res Interact Mark. Vaterlaus JM, Patten EV, Roche C, Young JA. Gettinghealthy: the perceived influence of social media on young adult health behaviors. Comput Hum Behav. Easton S, Morton K, Tappy Z, Francis D, Dennison L. Thomas DT, Erdman KA, Burke LM. Position of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, Dietitians of Canada, and the American College of Sports Medicine: nutrition and athletic performance. J Acad Nutr Diet. Pegoraro A, Kennedy H, Agha N, Brown N, Berri D. An analysis of broadcasting media using social media engagement in the WNBA. Front Sports Act Living. Carrotte ER, Vella AM, Lim MS. Boepple L, Thompson JK. A content analytic comparison of fitspiration and thinspiration websites. Schoenenberg K, Martin A. Bedeutung von Instagram und Fitspiration-Bildern für die muskeldysmorphe Symptomatik. Jiotsa B, Naccache B, Duval M, Rocher B, Grall-Bronnec M. Raggatt M, Wright CJC, Carrotte E, et al. Frederick DA, Reynolds TA. The value of integrating evolutionary and sociocultural perspectives on body image. Arch Sex Behav. McClendon E. Fashion and physique: size, shape, and body politics in the display of historical dress. In: Cooks BR, Wagelie JJ, editors. Mannequins in museums: power and resistance on display. London: Routledge; Chapter Google Scholar. A systematic review of the impact of the use of social networking sites on body image and disordered eating outcomes. Mills JS, Musto S, Williams L, Tiggemann M. Download references. Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. This research received no external funding. Institut für Sportwissenschaft, Universität der Bundeswehr München, Neubiberg, Germany. Institut für Kreislaufforschung und Sportmedizin, Deutsche Sporthochschule Köln, Cologne, Germany. You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar. KK, TR and KB conceptualized the study; TR conducted the investigation and was in contact with participants; KK and TR curated the data; KK and TR carried out statistical analysis; KK wrote the original draft; KB reviewed and edited the writing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Correspondence to Kristina Klier. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. See Tables 3 , 4 and 5. See Fig. Sport-related usage motives are presented in accordance to the number of participants for the total sample a and differentiated to the age groups b , c. Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. Reprints and permissions. Klier, K. fitspiration: a comparison of the sport-related social media usage and its impact on body image in young adults. BMC Psychol 10 , Using fruit to describe body types has long been seen by some as a visual shorthand; a way to describe the shape in a less technical or scientific way. In a study on objectification theory , researchers Barbara Fredrickson and Tomi-Ann Roberts write:. Accumulations of such experiences may help account for an array of mental health risks that disproportionately affect women: unipolar depression, sexual dysfunction, and eating disorders. If you want a little help, you can always take your measurements and use those figures to help guide you. Have a friend or someone else you trust measure across your back from the edge of one shoulder to the other. Place one end of the tape measure on the fullest part of your bust, then wrap it around yourself. Make sure to go under your armpits and around your shoulder blades. Hold one end of the measuring tape on the front of one of your hips, then wrap the measuring tape around yourself. Make sure you go over the largest part of your buttocks. For example, some people have a curvier, rounder buttocks and curvature in their spine. By the time you reach adulthood, your bone structure and proportions are largely established — even if your measurements change as you gain or lose weight. Some may find that they typically store fat in their mid-section, while others may put weight on in their thighs, legs, or arms first. For example, stress can trigger your body to release the hormone cortisol. Research suggests that stress-induced cortisol may be tied to fat buildup around your most vital organs in your mid-section. Estrogen and progesterone, released by sexual organs, can also affect how your body stores fat. Estrogen, for example, can lead your body to store fat in your lower abdomen. Older adults tend to have higher levels of body fat overall. Two contributing factors include a slowing metabolism and gradual loss of muscle tissue. Aging can also affect mobility, resulting in a more sedentary lifestyle. This could lead to weight gain. Aging can even affect your height. Many people find that they gradually become shorter after age This can affect how your body looks overall. According to a review , menopause may also change your body shape and fat distribution by redistributing more weight to your abdomen. If you want to change certain things about yourself — for you and because you want to — exercise could make a difference. For example, you might be able to give your arms more muscle definition with regular training. Research has also found that genetic factors can affect your resting metabolic rate. If you have any concerns about your body — including how it feels or the way it moves — talk to a doctor or other healthcare provider. Simone M. Scully is a writer who loves writing about all things health and science. Find Simone on her website , Facebook , and Twitter. Our experts continually monitor the health and wellness space, and we update our articles when new information becomes available. Body checking involves examining or measuring something related to your body, usually your weight, size, or shape. |

Body comparison -

Vandenbosch L, Fardouly J, Tiggemann M. Social media and body image: recent trends and future directions. Curr Opin Psychol. Rodgers RF, Paxton SJ, Wertheim EH. Take idealized bodies out of the picture: a scoping review of social media content aiming to protect and promote positive body image.

Tiggemann M, Zaccardo M. J Health Psychol. Cwynar-Horta J. The commodification of the body positive movement on Instagram. Stream Interdiscip J Commun. Betz DE, Ramsey LR. Holland G, Tiggemann M. Int J Eat Disord. Kim J, Uddin ZA, Lee Y, et al. A systematic review of the validity of screening depression through Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and Snapchat.

J Affect Disord. Cataldo I, De Luca I, Giorgetti V, et al. Fitspiration on social media: body-image and other psychopathological risks among young adults. A narrative review. Emerg Trends Drugs Addict Health.

Barron AM, Krumrei-Mancuso EJ, Harriger JA. The effects of fitspiration and self-compassion Instagram posts on body image and self-compassion in men and women.

Cohen R, Blaszczynski A. Comparative effects of Facebook and conventional media on body image dissatisfaction. J Eat Disord. Lev-Ari L, Baumgarten-Katz I, Zohar AH. Show me your friends, and I shall show you who you are: the way attachment and social comparisons influence body dissatisfaction.

Eur Eat Disord Rev. Uhlmann LR, Donovan CL, Zimmer-Gembeck MJ, Bell HS, Ramme RA. Homan K. Athletic-ideal and thin-ideal internalization as prospective predictors of body dissatisfaction, dieting, and compulsive exercise.

Cohen R, Newton-John T, Slater A. The case for body positivity on social media: perspectives on current advances and future directions. Anixiadis F, Wertheim EH, Rodgers R, Caruana B.

Effects of thin-ideal Instagram images: the roles of appearance comparisons, internalization of the thin ideal and critical media processing. Clement U, Löwe B. Der" Fragebogen zum Körperbild FKB ". Literaturüberblick, Beschreibung und Prüfung eines Messinstrumentes. Google Scholar.

Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. New York: Academic Press; Albani C, Blaser G, Geyer M, et al. Überprüfung und Normierung des" Fragebogen zum Körperbild" FKB von Clement und Löwe an einer repräsentativen deutschen Bevölkerungsstichprobe.

Z Med Psychol. Liu R, Menhas R, Dai J, Saqib ZA, Peng X. Fitness apps, live streaming workout classes, and virtual reality fitness for physical activity during the COVID lockdown: an empirical study.

Front Public Health. Brierley ME, Brooks KR, Mond J, Stevenson RJ, Stephen ID. PLoS ONE. Aanesen SM, Notøy RRG, Berg H. The Re-shaping of bodies: a discourse analysis of feminine athleticism.

Front Psychol. Mayoh J, Jones I. J Med Internet Res. Carrotte ER, Prichard I, Lim MS. Kaczinski A, Hennig-Thurau T, Sattler H. Accessed 28 July Pelletier MJ, Krallman A, Adams FG, Hancock T.

J Res Interact Mark. Vaterlaus JM, Patten EV, Roche C, Young JA. Gettinghealthy: the perceived influence of social media on young adult health behaviors. Comput Hum Behav. Easton S, Morton K, Tappy Z, Francis D, Dennison L. Thomas DT, Erdman KA, Burke LM. Position of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, Dietitians of Canada, and the American College of Sports Medicine: nutrition and athletic performance.

J Acad Nutr Diet. Pegoraro A, Kennedy H, Agha N, Brown N, Berri D. An analysis of broadcasting media using social media engagement in the WNBA. Front Sports Act Living. Carrotte ER, Vella AM, Lim MS. Boepple L, Thompson JK. A content analytic comparison of fitspiration and thinspiration websites.

Schoenenberg K, Martin A. Bedeutung von Instagram und Fitspiration-Bildern für die muskeldysmorphe Symptomatik. Jiotsa B, Naccache B, Duval M, Rocher B, Grall-Bronnec M.

Raggatt M, Wright CJC, Carrotte E, et al. Frederick DA, Reynolds TA. The value of integrating evolutionary and sociocultural perspectives on body image. Arch Sex Behav. McClendon E. Fashion and physique: size, shape, and body politics in the display of historical dress.

In: Cooks BR, Wagelie JJ, editors. Mannequins in museums: power and resistance on display. London: Routledge; Chapter Google Scholar. A systematic review of the impact of the use of social networking sites on body image and disordered eating outcomes.

Mills JS, Musto S, Williams L, Tiggemann M. Download references. Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. This research received no external funding. Institut für Sportwissenschaft, Universität der Bundeswehr München, Neubiberg, Germany.

Institut für Kreislaufforschung und Sportmedizin, Deutsche Sporthochschule Köln, Cologne, Germany. You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar. KK, TR and KB conceptualized the study; TR conducted the investigation and was in contact with participants; KK and TR curated the data; KK and TR carried out statistical analysis; KK wrote the original draft; KB reviewed and edited the writing.

All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Correspondence to Kristina Klier. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

See Tables 3 , 4 and 5. See Fig. Sport-related usage motives are presented in accordance to the number of participants for the total sample a and differentiated to the age groups b , c.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material.

If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. Reprints and permissions. Klier, K.

fitspiration: a comparison of the sport-related social media usage and its impact on body image in young adults. BMC Psychol 10 , Download citation.

Received : 08 August Accepted : 19 December Published : 27 December Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:. Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative. Skip to main content. Search all BMC articles Search. Download PDF. Abstract Background Following and posting sport-related content on social media is wide-spread among young people. Conclusions These results reveal the importance of taking a closer look at socially shaped beauty and body ideals, especially in sport-related contents, striving for more educational campaigns such as Body Positivity and, above all, filtering information.

Introduction Nowadays, almost all young people use social media [ 1 ]. Methods Participants In total, participants, of them Material The used online questionnaire comprised five parts.

Statistical analysis The statistical analysis was carried out using the Statistic Software SPSS Body image When asked whether the participants knew ideals of beauty and body shape, Table 2 Classification of body image groups Full size table.

Matsuoka K, et al. Brett M, et al. Region of interest analysis using an SPM toolbox. Sendai: 8th international conference on functional mapping of the human brain; Woo CW, Krishnan A, Wager TD.

Cluster-extent based thresholding in fMRI analyses: pitfalls and recommendations. Srinivasagam NM, et al. Persistent perfectionism, symmetry, and exactness after long-term recovery from anorexia nervosa.

Downing PE, et al. A cortical area selective for visual processing of the human body. Suchan B, et al. Reduction of gray matter density in the extrastriate body area in women with anorexia nervosa.

Behav Brain Res. Uher R, et al. Functional neuroanatomy of body shape perception in healthy and eating-disordered women. Biol Psychiatry. Reduced connectivity between the left fusiform body area and the extrastriate body area in anorexia nervosa is associated with body image distortion.

The role of the extrastriate body area in action perception. Soc Neurosci. Urgesi C, Berlucchi G, Aglioti SM. Magnetic stimulation of extrastriate body area impairs visual processing of nonfacial body parts. Curr Biol. Carter JC, et al. Relapse in anorexia nervosa: a survival analysis. Psychol Med.

Keel PK, et al. Postremission predictors of relapse in women with eating disorders. Etkin A, et al. Toward a neurobiology of psychotherapy: basic science and clinical applications.

J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. Nitschke JB, Mackiewicz KL. Prefrontal and anterior cingulate contributions to volition in depression.

Int Rev Neurobiol. Brambilla F, et al. Persistent amenorrhoea in weight-recovered anorexics: psychological and biological aspects.

Schneider N, et al. Psychopathology in underweight and weight-recovered females with anorexia nervosa. Eat Weight Disord. Brockhoff M, et al. Cultural differences in body dissatisfaction: Japanese adolescents compared with adolescents from China, Malaysia, Australia, Tonga, and Fiji.

Asian J Soc Psychol. Bastiani AM, et al. Perfectionism in anorexia nervosa. Sullivan PF, et al. Outcome of anorexia nervosa: a case-control study. Karlsson GP, Clinton D, Nevonen L. Prediction of weight increase in anorexia nervosa.

Nord J Psychiatry. Anderluh MB, et al. Childhood obsessive-compulsive personality traits in adult women with eating disorders: defining a broader eating disorder phenotype.

Fairburn CG, et al. Risk factors for anorexia nervosa: three integrated case-control comparisons. Arch Gen Psychiatry. Silver MA, Ress D, Heeger DJ.

Neural correlates of sustained spatial attention in human early visual cortex. J Neurophysiol. Ress D, Backus BT, Heeger DJ. Activity in primary visual cortex predicts performance in a visual detection task. Nat Neurosci. Gilon Mann T, et al. Eur Eat Disord Rev.

Wright CI, et al. Differential prefrontal cortex and amygdala habituation to repeatedly presented emotional stimuli. Plichta MM, et al. Amygdala habituation: a reliable fMRI phenotype. Normal brain tissue volumes after long-term recovery in anorexia and bulimia nervosa. Download references.

The authors acknowledge the co-operation and contribution of the staff and the women who participated in this study. Division of Psychosomatic Medicine, Department of Neurology, University of Occupational and Environmental Health, Kitakyushu, , Japan.

Department of Psychophysiology, National Institute of Mental Health, National Center of Neurology and Psychiatry, Tokyo, , Japan. NPO Corporation Nobinokai, Yokohama, , Japan. College of Art and Design, Joshibi University of Art and Design, Sagamihara, , Japan.

Department of Psychosomatic Research, National Institute of Mental Health, National Center of Neurology and Psychiatry, Tokyo, , Japan. Department of Psychosomatic Medicine, Center Hospital of the National Center for Global Health and Medicine, Tokyo, , Japan. Department of Psychosomatic Medicine, Graduate School of Medical Sciences, Kyushu University, Fukuoka, , Japan.

Department of Neurology, University of Occupational and Environmental Health, Kitakyushu, , Japan. School of Health Sciences Fukuoka, International University of Health and Welfare, Fukuoka, , Japan. You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar.

NK, YM, MM, TA, HK, MG and GK designed the research. NK, AT and MM collected the data. NK, YM and HA analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript.

All authors have approved the final manuscript. Correspondence to Naoki Kodama. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the National Center of Neurology and Psychiatry, Tokyo, Japan. All participants provided informed consent. We managed the data to ensure that the participants were not identified.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. Table S1. Table S2. Table S3. Table S4. Table S5. DOCX 25 kb. Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.

Reprints and permissions. Kodama, N. et al. Neural correlates of body comparison and weight estimation in weight-recovered anorexia nervosa: a functional magnetic resonance imaging study. BioPsychoSocial Med 12 , 15 Download citation. Received : 19 May Accepted : 14 October Published : 31 October Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:.

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative. Skip to main content. Search all BMC articles Search. Download PDF. Research Open access Published: 31 October Neural correlates of body comparison and weight estimation in weight-recovered anorexia nervosa: a functional magnetic resonance imaging study Naoki Kodama ORCID: orcid.

Abstract Background The neural mechanisms underlying body dissatisfaction and emotional problems evoked by social comparisons in patients with anorexia nervosa AN are currently unclear. Methods We used fMRI to examine 12 patients with recAN and 13 healthy controls while they performed body comparison and weight estimation tasks with images of underweight, healthy weight, and overweight female bodies.

Results We found that, compared to healthy controls, patients with recAN exhibited significantly greater activation in the pregenual anterior cingulate cortex pgACC when comparing their own bodies with images of underweight female bodies.

Conclusions Our findings from a group of patients with recAN suggest that the pathology of AN may lie in an inability to regulate negative affect in response to body images via pgACC activation during body comparisons.

Background Anorexia nervosa AN is a disorder of unknown etiology, mostly affecting young women. Methods The study was approved by the local Ethics Committee National Center of Neurology and Psychiatry and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Table 1 Comparisons of demographic and clinical characteristics between the patient and control groups Full size table. Full size image. Results Baseline characteristics There were no group differences in demographic variables Table 1. Table 3 Rating scores for the comparison task and weight estimation task Full size table.

Table 4 7-point scale for anxiety and VAS scores for weight estimation Full size table. Discussion In the current study, we investigated the neural underpinnings of body shape comparisons and weight estimation in patients with recAN.

Conclusions The current study revealed that patients with recAN exhibited greater pregenual ACC activation than did controls during comparisons of their own body with underweight female body images.

References Jacobi C, et al. Article Google Scholar Stice E. Article Google Scholar Stice E, Shaw HE. Article Google Scholar Groesz LM, Levine MP, Murnen SK. Article Google Scholar Thompson JK, et al. Book Google Scholar Brown A, Dittmar H.

Article Google Scholar Grabe S, Ward LM, Hyde JS. Article Google Scholar Festinger L. Article Google Scholar Hamel AE, et al. Article Google Scholar Friederich HC, et al. Article Google Scholar Strigo IA, et al. Article Google Scholar Wagner A, et al. Article Google Scholar Sheng M, et al. Article Google Scholar Frank GK, et al.

Article Google Scholar Rosen JC, et al. Article Google Scholar Sheehan, D. Article Google Scholar Fladung AK, et al. Article Google Scholar Pruis TA, Keel PK, Janowsky JS.

Article Google Scholar Morris JP, Pelphrey KA, McCarthy G. Lee SY, Gallagher D. Assessment methods in human body composition. Current opinion in clinical nutrition and metabolic care. Kyle UG, Bosaeus I, De Lorenzo AD, Deurenberg P, Elia M, Gomez JM, et al. Bioelectrical impedance analysis—part I: review of principles and methods.

Clin Nutr. Gonzalez MC, Barbosa-Silva TG, Bielemann RM, Gallagher D, Heymsfield SB. Phase angle and its determinants in healthy subjects: influence of body composition. The American journal of clinical nutrition. Genton L, Herrmann FR, Sporri A, Graf CE. Association of mortality and phase angle measured by different bioelectrical impedance analysis BIA devices.

View Article Google Scholar Vassilev G, Hasenberg T, Krammer J, Kienle P, Ronellenfitsch U, Otto M. The Phase Angle of the Bioelectrical Impedance Analysis as Predictor of Post-Bariatric Weight Loss Outcome.

Obes Surg. Dos Santos L, Cyrino ES, Antunes M, Santos DA, Sardinha LB. Changes in phase angle and body composition induced by resistance training in older women. Eur J Clin Nutr. Kyle UG, Bosaeus I, De Lorenzo AD, Deurenberg P, Elia M, Manuel Gomez J, et al.

Bioelectrical impedance analysis-part II: utilization in clinical practice. Deurenberg P. Limitations of the bioelectrical impedance method for the assessment of body fat in severe obesity. Waki M, Kral JG, Mazariegos M, Wang J, Pierson RN Jr.

Relative expansion of extracellular fluid in obese vs. nonobese women. The American journal of physiology. Ellegard L, Bertz F, Winkvist A, Bosaeus I, Brekke HK. Body composition in overweight and obese women postpartum: bioimpedance methods validated by dual energy X-ray absorptiometry and doubly labeled water.

Bosaeus M, Karlsson T, Holmang A, Ellegard L. Accuracy of quantitative magnetic resonance and eight-electrode bioelectrical impedance analysis in normal weight and obese women. Sartorio A, Malavolti M, Agosti F, Marinone PG, Caiti O, Battistini N, et al.

Body water distribution in severe obesity and its assessment from eight-polar bioelectrical impedance analysis. Stewart SP, Bramley PN, Heighton R, Green JH, Horsman A, Losowsky MS, et al. Estimation of body composition from bioelectrical impedance of body segments: comparison with dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry.

Br J Nutr. Thomson R, Brinkworth GD, Buckley JD, Noakes M, Clifton PM. Good agreement between bioelectrical impedance and dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry for estimating changes in body composition during weight loss in overweight young women.

Pateyjohns IR, Brinkworth GD, Buckley JD, Noakes M, Clifton PM. Comparison of three bioelectrical impedance methods with DXA in overweight and obese men.