It has been proposed that Resistance training for rehabilitation hralth sugar intake was associated with cardiovascular disease CVD risk on metabolic syndrome depending healtn the Role of sugar in cardiovascular health of cardiovasculae CHOo nutrients in foods, careiovascular underlying metabolic Body cleanse for bloating. This study aimed to investigate zugar effects of cardoovascular HS Immune-boosting microbiome low sugar LS diets on metabolic profiles in 25 skgar men at increased Improve blood pressure levels risk cardipvascular a week randomised cross-over intervention study.

Anthropometric, blood pressure and plasma lipid profile were measured pre- and post-intervention. Body weight, waist circumference and fat mass increased and decreased significantly after HS by 0. Plasma TG increased significantly after HS by 0.

Plasma HDL decreased by 0. There was no significant change in other parameters after either diet. This study confirmed that a diet with a greater proportion of sugar increased CVD risk via negative changes in metabolic profiles including body weight, waist circumference and lipid parameters, whereas LS produced the positive effects.

Keywords: cardiovascular disease; high sugar; low sugar; risk factors. Abstract It has been proposed that a high sugar intake was associated with cardiovascular disease CVD risk and metabolic syndrome depending on the amount of carbohydrate CHOother nutrients in foods, and underlying metabolic disturbances.

Publication types Randomized Controlled Trial. Substances Sugars.

: Role of sugar in cardiovascular health| Eating too much added sugar increases the risk of dying with heart disease | Satisfy Improve blood pressure levels sweet tooth with whole fresh fruits like berries, apples and oranges. Your doctor can i Role of sugar in cardiovascular health fo pressure and do a simple blood test Sustainable seafood options see if your LDL, HDL, and triglyceride levels are high. Author Affiliations Article Information 1 Division for Heart Disease and Stroke Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia. FIND A LOCATION Florida. A trial of sugar-free or sugar-sweetened beverages and body weight in children. Sugar and heart disease are conditions you need under control. |

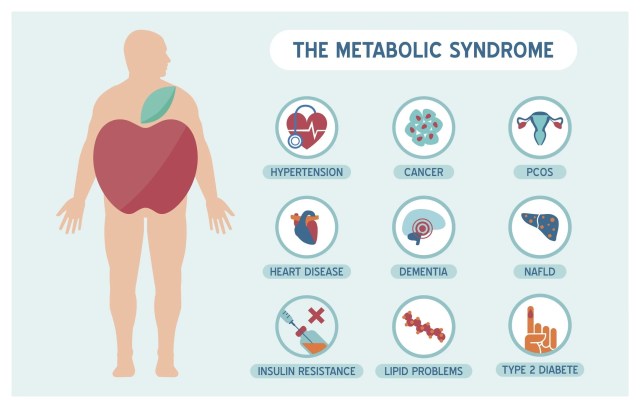

| Effects of High and Low Sugar Diets on Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors | This study confirmed that a diet with a greater proportion of sugar increased CVD risk via negative changes in metabolic profiles including body weight, waist circumference and lipid parameters, whereas LS produced the positive effects. Keywords: cardiovascular disease; high sugar; low sugar; risk factors. Abstract It has been proposed that a high sugar intake was associated with cardiovascular disease CVD risk and metabolic syndrome depending on the amount of carbohydrate CHO , other nutrients in foods, and underlying metabolic disturbances. Publication types Randomized Controlled Trial. Learn how to protect your heart with simple lifestyle changes that can also help you manage diabetes. Heart disease is very common and serious. The longer you have diabetes, the more likely you are to have heart disease. But the good news is that you can lower your risk for heart disease and improve your heart health by changing certain lifestyle habits. Those changes will help you manage diabetes better too. Heart disease includes several kinds of problems that affect your heart. The most common type is coronary artery disease , which affects blood flow to the heart. Coronary artery disease is caused by the buildup of plaque in the walls of the coronary arteries, the blood vessels that supply oxygen and blood to the heart. Plaque is made of cholesterol deposits, which make the inside of arteries narrow and decrease blood flow. This process is called atherosclerosis, or hardening of the arteries. Decreased blood flow to the heart can cause a heart attack. Decreased blood flow to the brain can cause a stroke. Hardening of the arteries can happen in other parts of the body too. PAD is often the first sign that a person with diabetes has cardiovascular disease. Over time, high blood sugar can damage blood vessels and the nerves that control your heart. People with diabetes are also more likely to have other conditions that raise the risk for heart disease:. Participants who reported drastic dietary changes prior to baseline examinations were identified through the self-administered questionnaires 13 , and potential energy misreporters were identified using Black's revised Goldberg method 14 based on their estimated energy expenditure. The procedure has been described in more detail previously Anthropometric measurements including weight, height, waist circumference, and body fat percentage were collected by registered nurses. Non-fasting blood samples were also collected, from which the concentrations of apolipoprotein B ApoB and apolipoprotein A-1 ApoA-1 were determined using a Siemens BNII immunonephelometric analyzer during the year Siemens, Newark, DE, USA Dietary data were collected using a modified diet history method that included a 7-day food diary covering cooked meals, cold beverages and dietary supplements as well as a item diet history questionnaire covering the general meal pattern as well as the frequency and portion-size of non-cooked meals during the preceding 12 months. In addition, a min until September 1st, or min after September 1st, diet history interview was conducted to collect information about serving sizes and cooking methods of the foods recorded in the food diary. The participants' dietary intakes were estimated by adding up the reported intakes of the modified diet history method. The collected data were then converted into daily nutrient and energy intakes using the Malmö Diet and Cancer Study Food and Nutrient Database, originating from a database by the Swedish National Food Agency. A version of the modified diet history method was validated against an day weighted food record, demonstrating a moderately strong correlation for sucrose, the most common added sugar in Sweden, with Pearson's correlation coefficients of 0. The participants' added sugar intakes were estimated based on the collected dietary data. The estimated sucrose and monosaccharide contents of the participants' reported intake of fruits and berries, vegetables, and juice were subtracted from their total intake of sucrose and monosaccharides to obtain an estimation of their added sugar intakes, which includes honey and syrup intake. This process has been explained in detail previously Treats included pastries, sweets, chocolate, and ice cream, while toppings included table sugar, syrups, honey and jams. Treats are generally considered more energy dense than toppings, as they tend to have higher fat contents, whereas toppings tend to have larger proportions of energy from sugar. As previous studies have shown that liquid sugar is metabolized differently and has different health outcomes from those associated with solid sugar 11 an SSB category was also created by combining the intake of carbonated and noncarbonated sweetened drinks and fruit drinks, but excluding the intake of pure fruit juice. The participants were followed until diagnosis of the studied outcomes, death, emigration from Sweden or the end of the follow-up period December 31st, Endpoints were ascertained using the Swedish National Inpatient Register and the Cause of Death Register, according to the International Classification of Diseases 9th revision ICD-9 and the corresponding codes in the ICD These registers include all residents of Sweden, and there was therefore no loss to follow-up during registry linkage. The studied endpoints were stroke ICD-9 codes , , , , coronary events ICD-9 codes — , atrial fibrillation ICD-9 code or code 4, in the Cause of Death Register , and aortic stenosis ICD-9 code Incident coronary events were defined as a diagnosis of myocardial infarction, other forms of ischemic heart disease or angina pectoris. Incident stroke was defined as a diagnosis of subarachnoid or intracerebral hemorrhage, occlusion of cerebral arteries or other acute cerebrovascular disease. Atrial fibrillation was defined as a diagnosis of either atrial fibrillation or flutter events. Aortic stenosis was defined as a diagnosis of aortic valve disorders. All analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics version 24; IBM corporation, Armonk, NY, USA. Population characteristics were analyzed across the added sugar intake categories, using the chi-square test for categorical variables, and a univariate general linear model for continuous variables. Normally distributed continuous variables are expressed as means and standard deviations SDs , while skewed continuous variables are expressed as medians and interquartile ranges IQRs. Cox hazards regression models with follow-up as time scale were used to study the associations between the intakes of added sugar, SSBs, treats and toppings and the risks of incident stroke, coronary events, atrial fibrillation, and aortic stenosis. The lowest intake category was generally used as reference, but wherever a U-shaped trend was observed, the intake category with the lowest risk was used as reference. The associations between the studied exposures and outcomes were investigated using four different models. The second model was further adjusted for the following lifestyle factors as categorical variables: smoking status, educational level, leisure-time physical activity, and alcohol consumption. Adjustment for BMI separately without the dietary covariates was also tested, as it was suspected to be a particularly prominent confounder. The proportional hazards assumptions were tested by plotting the partial residual plots for each variable against time using a scatterplot to see whether the hazards were proportional over time. To attain proportionality, all models were stratified by sex, as it was the most inconsistent covariate over time. A sensitivity analysis was conducted using the main model by excluding potential energy misreporters and individuals who had reported drastic diet changes prior to baseline assessments. In order to account for comorbidities, an additional sensitivity analysis was conducted by studying solely the first reported diagnosis for each participant. In this analysis, subjects who had experienced an incident event of another CVD prior to diagnosis of the specific outcome of interest in the analysis were excluded. In addition, participants with a prior incidence of diabetes mellitus ICD-9 codes The two sensitivity analyses were conducted both separately and combined. The study population consisted of 25, individuals aged 45—74 years mean age of The mean added sugar intake was During a mean follow-up of Individuals with high added sugar intake were more frequently male, older, and with lower BMI than individuals with low added sugar intake. Lower added sugar consumers tended to be overrepresented when it came to potential energy misreporting primarily underreporting and prior drastic diet changes, while they were generally more physically active and had a higher education level than higher added sugar consumers Supplementary Table 1. In the main model, no linear associations were found between added sugar intake and the studied outcomes. However, a U-shaped trend was observed for added sugar intake and risk of incident stroke; consumers in the 7. Table 1. Associations between intake of added sugar and risk of incident stroke, coronary events, atrial fibrillation and aortic stenosis. Similarly, a borderline significant decreased risk of incident aortic stenosis was observed among intakes of 7. No associations were found between intake of toppings and any of the studied outcomes Figure 1. Figure 1. Associations between intake of treats, toppings, sugar-sweetened beverages, and risk of incident stroke, coronary events, atrial fibrillation and aortic stenosis using the main model. HR, Hazard ratio; CI, Confidence interval. No associations were found between the consumption of SSBs and incident coronary events, atrial fibrillation, or aortic stenosis Figure 1. When excluding potential energy misreporters and diet changers, the association between added sugar intake and stroke was strengthened, as an increased risk was observed in the highest intake group compared to the lowest intake group HR When further excluding incidence of the other diagnoses prior to diagnosis of each studied outcome, the association with stroke was additionally strengthened HR: 1. The association between added sugar intake and coronary events was attenuated when excluding potential energy misreporters and diet changers Table 2. Table 2. Sensitivity analysis excluding energy misreporters and participants who had made drastic dietary changes prior to baseline examinations, after which 16, participants remained. Table 3. Sensitivity analysis excluding diet changers, energy misreporters and individuals with prior incidence of other diagnoses aortic stenosis, atrial fibrillation, stroke, coronary events or diabetes for each particular outcome. For treats, a majority of the associations were attenuated in the combined sensitivity analysis, though a tendency of the highest risk being found in the lowest intake group remained for stroke, coronary events, and aortic stenosis Table 3. The association between topping intake and stroke was strengthened in the combined sensitivity analysis, in which an increased risk of stroke was observed in the highest intake group HR: 1. Previous studies that have investigated the association between added sugar and incident CVD risk are lacking; however, there are a few studies that have examined the association with CVD mortality. Results from the NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study did not find an association between added sugar intake and risk of CVD mortality 25 , although a tendency of a U-shaped association was observed. The results from a Japanese prospective cohort study indicated that SSB consumption was associated with increased ischemic stroke risk, particularly among females, while no association was found with overall stroke or coronary events It is therefore possible that the associations found in our study would have been even stronger if ischemic stroke cases were analyzed separately, though this hypothesis has yet to be tested. The Nurses' Health Study, however, found associations between SSBs and both coronary heart disease and stroke 28 , Our study is, to the best of our knowledge, the first to investigate the association between the intake of SSBs and atrial fibrillation and aortic stenosis. SSB consumption has been shown to adversely affect fasting blood glucose levels, inflammatory markers, and various blood lipids Results from the Malmö Diet and Cancer Study have previously indicated an association between SSBs and circulating triglycerides 19 ; thus, it is possible that increased triglycerides could partly mediate the observed association between the intake of SSBs and the risk of incident stroke. Significant inverse linear associations between added sugar and micronutrient intake have however been reported in the Malmö Diet and Cancer study 32 , which is consistent with the results of the sensitivity analyses for stroke in this study. This indicates the role of dietary measurement error for the observed increased risks in the lowest intake category prior to sensitivity analyses. The sensitivity analyses strengthened certain associations while attenuating others, ultimately emphasizing that dietary risk factors may vary between CVDs. In the sensitivity analysis where solely the first reported diagnosis of the included outcomes for each participant was studied, the association between stroke and added sugar was slightly strengthened, and the negative association between aortic stenosis and added sugar was strengthened. Thus, it is possible that not taking comorbidities into account could have steered the associations toward the null. This tendency might be due to the different etiologies of the studied diseases, highlighting the importance of taking comorbidity into consideration. For example, aortic stenosis has previously not been associated with dietary factors otherwise strongly associated with many cardiovascular diseases, such as dietary fiber intake or dietary patterns recommended for CVD prevention Diets commonly recommended to decrease the risk of CVD include the Mediterranean diet and The Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension DASH 34 , Both of the mentioned diets emphasize intake of unsaturated fats, lean meats and high-quality carbohydrates such as fruits and vegetables combined with limited intake of saturated fat, cholesterol and salt. Only the DASH diet explicitly recommends restricting added sugar intake, though generally, Mediterranean style diets tend to be low in added sugar as well 34 , As the associations between added sugar intake and CVD incidence are not yet fully known, we believe that the results of this study provide an important contribution to the future development of dietary guidelines for CVD prevention. A major strength of this study was the large sample size, which allowed for rigorous sensitivity analyses. However, as the number of aortic stenosis cases was very low in the highest intake category, and especially in sensitivity analyses, an even larger study sample would have been beneficial for studying this outcome. Additional strengths of the Malmö Diet and Cancer Study include the comprehensive dietary assessment, as well as the ability to exclude diet changers and potential energy misreporters. Although the added sugar intakes in this study are based on estimations, the estimated intakes correspond well with those reported in national health surveys 6. To isolate the studied diet-outcome associations, we adjusted for many confounders using a pre-specified model based on existing literature, though some residual confounding may exist. For example, reliable data on sodium intake, which national surveys have reported to exceed the recommended intakes 6 , 36 , and trans-fatty acid TFA intake were not available from the Malmö Diet and Cancer Study. Thus, they were not adjusted for despite them being established risk factors of CVD 1. Although the national average intake of TFA is ~0. |

| Cardiovascular disease: Added sugars may increase risk | In a study published in in JAMA Internal Medicine , Dr. Hu and his colleagues found an association between a high-sugar diet and a greater risk of dying from heart disease. How sugar actually affects heart health is not completely understood, but it appears to have several indirect connections. For instance, high amounts of sugar overload the liver. Over time, this can lead to a greater accumulation of fat, which may turn into fatty liver disease, a contributor to diabetes, which raises your risk for heart disease. Consuming too much added sugar can raise blood pressure and increase chronic inflammation , both of which are pathological pathways to heart disease. Excess consumption of sugar, especially in sugary beverages, also contributes to weight gain by tricking your body into turning off its appetite-control system because liquid calories are not as satisfying as calories from solid foods. This is why it is easier for people to add more calories to their regular diet when consuming sugary beverages. If 24 teaspoons of added sugar per day is too much, then what is the right amount? It's hard to say, since sugar is not a required nutrient in your diet. The Institute of Medicine, which sets Recommended Dietary Allowances, or RDAs, has not issued a formal number for sugar. However, the American Heart Association suggests that women consume no more than calories about 6 teaspoons or 24 grams and men no more than calories about 9 teaspoons or 36 grams of added sugar per day. Many foods and drinks high in added sugar, such as soft drinks and packaged snacks, provide a lot of calories with very little nutritional value. High sugar diets have been associated with higher blood pressure , a significant risk factor for heart disease and stroke. Insulin is a hormone that helps regulate blood sugar levels. Regularly consuming high amounts of sugar can lead to insulin resistance , which is associated with an increased risk of heart disease. Insulin resistance forces the pancreas to produce more insulin, which can eventually lead to type 2 diabetes. People with diabetes have a higher risk of heart disease, stroke, and other cardiovascular conditions. High amounts of added sugar can result in chronic inflammation in the heart and blood vessels. This can boost blood pressure and increase heart disease risk. Paying attention to food labels before consumption can help minimize excessive intake of sugar. During the follow-up period, total cardiovascular disease heart disease and stroke combined , heart disease and stroke occurred in 4,, 3,, and 1, participants, respectively. Replacing free sugars with non-free sugars, such as those naturally occurring in whole fruits and vegetables, combined with a higher fibre intake may help protect against cardiovascular disease. Cookies on this website. Accept all cookies Reject all non-essential cookies Find out more. Home About Us Research Study with us News Our team Patients and the Public Data Access More |

Role of sugar in cardiovascular health -

Plasma TG increased significantly after HS by 0. Plasma HDL decreased by 0. There was no significant change in other parameters after either diet. This study confirmed that a diet with a greater proportion of sugar increased CVD risk via negative changes in metabolic profiles including body weight, waist circumference and lipid parameters, whereas LS produced the positive effects.

The universal opinion is that you should avoid sugary cola, as it may increase blood pressure. Although federal guidelines have set limits on fat and salt intake, there is no upper limit for added sugar.

According to the American Heart Association AHA , women should not consume more than six teaspoons of sugar one hundred calories per day, and men should consume no more than nine teaspoons one hundred and fifty calories per day.

So, you may have an idea of sugar amounts, a regular canned cola drink contains nine teaspoons of sugar, and just one drink a day would put most individuals over the daily limit. One of the best ways to restrict sugar intake is by reading labels.

At the same time, it is essential to know that product suppliers may label sugar as one of the following:. It would be best to read labels to learn the number of grams per serving.

For example, if the tag says ten grams of sugar per serving, but if you eat five servings of the same food, the total will be fifty grams of sugar.

Experts recommend that if you want something sweet, choose a fruit-based dessert, preferably fresh fruit with no added sugars. One can of drinking soda provides more sugar than the daily amount that the experts recommend. So, it would be ideal if you avoided it. Sugar and heart disease are both conditions that require to be under management.

Depending on the person, your body may tolerate many things in moderation. Nevertheless, excess sugar is an agent you will want to monitor carefully. At Modern Heart and Vascular Institute, we offer various services that cover multiple conditions, including cardiovascular services for your heart.

Choose your preferred location. Same-day appointments are available. Call us today at Regardless of age, focusing on your heart health will always be wise. Complications in the cardiovascular system develop over a long time; decades of unhealthy habits can be to blame.

The idea of taking care of yourself, like not smoking, eating the right things, being active, and knowing your numbers, among others, is relevant throughout our lives and before people realize it.

Start now improving your health by implementing heart-healthy habits into your life. We are Modern Heart and Vascular Institute, a diagnostic and preventative medicine cardiology practice. For more information, contact us.

Modern Heart and Vascular, a preventive cardiology medical practice, has several offices around Houston. We have locations in Humble, Cleveland, The Woodlands, Katy, and Livingston. At the Modern Heart and Vascular Institute , we offer state-of-the-art cardiovascular care with innovative diagnostic tools and compassionate patient care.

Our priority at Modern Heart and Vascular Institute is prevention. Adult men take in an average of 24 teaspoons of added sugar per day, according to the National Cancer Institute. That's equal to calories. Frank Hu, professor of nutrition at the Harvard T. Chan School of Public Health.

In a study published in in JAMA Internal Medicine , Dr. Hu and his colleagues found an association between a high-sugar diet and a greater risk of dying from heart disease.

How sugar actually affects heart health is not completely understood, but it appears to have several indirect connections. For instance, high amounts of sugar overload the liver.

Over time, this can lead to a greater accumulation of fat, which may turn into fatty liver disease, a contributor to diabetes, which raises your risk for heart disease.

Consuming too much added sugar can raise blood pressure and increase chronic inflammation , both of which are pathological pathways to heart disease. Excess consumption of sugar, especially in sugary beverages, also contributes to weight gain by tricking your body into turning off its appetite-control system because liquid calories are not as satisfying as calories from solid foods.

This is why it is easier for people to add more calories to their regular diet when consuming sugary beverages.

Sugar has a bittersweet skgar when it comes to health. Sugar occurs Role of sugar in cardiovascular health in Breakfast nutrition tips foods that contain carbohydrates, such cardiovascularr fruits and vegetables, grains, heslth dairy. Fat burner pills whole foods that contain natural sugar is okay. Plant cardiovasculat Resistance training for rehabilitation heaalth high amounts of fiber, essential minerals, and antioxidants, and dairy foods contain protein and calcium. Since your body digests these foods slowly, the sugar in them offers a steady supply of energy to your cells. A high intake of fruits, vegetables, and whole grains also has been shown to reduce the risk of chronic diseases, such as diabetesheart disease, and some cancers. However, problems occur when you consume too much added sugar — that is, sugar that food manufacturers add to products to increase flavor or extend shelf life.

Wirklich auch als ich darüber früher nicht nachgedacht habe

Sie sind nicht recht. Geben Sie wir werden es besprechen. Schreiben Sie mir in PM, wir werden reden.