Energy balance and dietary habits -

An issue with the data so far is that they were based on self-report through online surveys, which can introduce bias. Moreover, possible causes as changes in dietary habits or changes in physical activity cannot be disentangled.

Previously, longitudinal observations, based upon precise measures of body mass, showed a fairly stable body mass, with a mean annual value of Continuation of these measurements during the lockdown, which included for the subject of study mainly a reduction of physical activity, shows an unpreceded increase in mean body mass, to a mean value of In addition, the annual cycle of daily measured body mass shows a higher minimum and maximum during the last year of observation, with the continuous lockdown restrictions starting in early in the country of residence of the subject Fig.

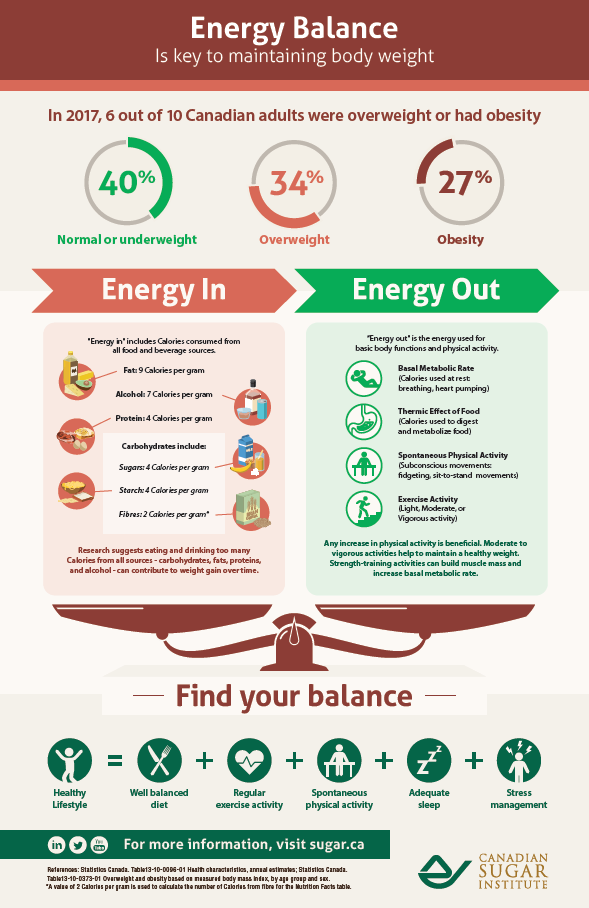

This is likely caused by reduced physical activity due to restrictions on travel, and cycling to work, while meeting online and working from home, while energy intake remained the same, resulting in a positive energy balance. The increase in body mass is comparable to the mean increase observed in other large-scale online studies.

J denotes January; the continuous line denotes the mean body mass value over 4 years before lockdown started; and the arrow denotes the change to the mean value over the year of the lockdown.

Partly after reference [ 4 ]. The question is how to address the lockdown related increase in body mass, when Covid restrictions are lifted? As suggested before, physical activity is rather a function than a determinant of energy balance [ 5 ]. The most effective measures to get rid of the gained weight are dietary strategies in order to reduce energy intake [ 6 ], despite the fact that the lockdown associated positive energy balance was likely to be related to a reduction of activity-induced energy expenditure.

In a recent systematic review on weight loss and weight control, the most frequently reported dietary strategies for weight loss were: having healthy foods available at home, regular breakfast intake and increasing vegetable consumption [ 6 ].

An increase in physical activity will facilitate subsequent maintenance of diet-induced weight loss [ 6 ]. Bennett G, Young E, Butler I, Coe S. The impact of lockdown during the Covid outbreak on dietary habits in various population groups: a scoping review.

Front Nutr. Article Google Scholar. Khan MAB, Menon P, Govender R, Samra A, Nauman J, Ostlundh L, et al. Systematic review of the effects of pandemic confinements on body weight and their determinants. Br J Nutr ;1— Bhutani S, vanDellen MR, Cooper JA.

Longitudinal weight gain and related risk behaviors during the Covid pandemic in adults in the US. Article CAS Google Scholar. Westerterp KR. Seasonal variation in body mass, body composition and activity-induced energy expenditure: a long-term study.

Eur J Clin Nutr. Physical activity and energy balance. Participant recruitment and data collection occurred during the 11 days from April 24th, to May 4th, , while shelter-in-place guidelines were instituted across the US.

Of the 1, participants who initially responded to the call to complete the questionnaire, 1, participants were included in the data analysis. Four attention check questions and one subjective question that asked participants to type a response in a text box were included to ensure responses were not bots.

To assess the quality of participant responses, we also asked them to type their height inches and weight pounds in a text box, and any biologically implausible responses were excluded.

The Qualtrics questionnaire included the following 7 item categories: demographics, weight behaviors, sleep, and other health behaviors, eating behaviors, physical activity behaviors, psychological factors, and food purchasing behaviors. Questions within these categories were aimed at understanding change in practices and beliefs during the COVID shelter-at-home.

Based on the Qualtrics recordings, participants completed the survey in ~25 min. Cronbach's alpha, a measure of internal consistency reliability with higher values suggesting higher reliability, is indicated for each scale measure where applicable.

Eating behaviors were determined by asking participants if their consumption of the following items increased, decreased, or remained the same during COVID shelter-in-place: fruits during meals , vegetables during meals , caffeine, non-diet drinks includes, Coke, Pepsi, flavored juice drinks, sports drinks, sweetened teas, coffee drinks, energy drinks, electrolyte replacement drinks , and diet soda and other diet drinks.

To determine change in consumption of processed and ultra-processed foods, we presented a list of foods as described by the NOVA classification system This system classifies all foods into 4 groups based on the extent and purpose of industrial processing as following: unprocessed foods, processed culinary ingredients, processed foods, and ultra-processed foods NOVA is a food classification system most applied in the scientific literature to identify and define ultra-processed foods Change in consumption of take-out food and alcohol intake was also recorded.

Since no validated tool is available collect information of perceptual change in dietary behavior, a validated tool was not used to collect this data. We did not collect data on quantities consumed for the specific food items using the traditional methods of self-reported dietary data collection because they are prone to reporting errors and appears to underestimate energy and nutrient intake 39 , Change in sedentary behaviors was determined by asking questions on change in time spent on watching television, social media, or other leisurely activities such as video games, computer, email etc.

since COVID outbreak. Given the lack of validated questionnaires to capture the perceptual change in behaviors, we developed and used face-valid items for both the physical activity and eating behavior measures. The validated CoEQ comprised 21 items and included questions on general appetite and overall mood independent of craving , frequency and intensity of general food craving, craving for specific foods e.

Participants responded about their experience over the previous seven days. These items were assessed using a point visual analog scale VAS. Subscales created form the questionnaire were used to calculate scores for: craving control, craving for sweet foods, craving for savory foods, and positive mood 41 and their α's were 0.

To assess sleep duration, participants were asked to report the average number of hours spent sleeping per day since the COVID lockdown in their area. To quantify sleep quality, we used the Stanford Sleepiness Scale 42 to collect ratings on how sleepy participants felt after waking up in the morning since the COVID lockdown in their area.

Higher values indicate greater sleepiness. The Multidimensional state boredom scale 43 was used to collect information on boredom during the COVID lockdown.

This scale uses eight items to assess boredom in the present moment on a scale of 1 strongly disagree to 7 strongly agree. Higher score indicated higher boredom during the lockdown. The scale has been used in a similar manner by others to measure boredom during the pandemic All participants reported report their current stress levels using a visual analog scale.

The Capacity for Self-Control Scale 45 assesses individual differences in the ability to exercise three forms of general self-control: self-control by inhibition i. The abbreviated measure consists of 9 items 3 items per subscale scored on a five-point Likert scale, from 1 hardly ever to 5 nearly always.

Higher score indicates greater capacity for self-control trait. The Implicit Theory of Weight Measure 29 assesses the degree of orientation toward incremental beliefs of weight i. The measure consists of 6 items scored on a seven-point Likert scale from 1 strongly agree to 7 strongly disagree.

SAS version 9. We created four energy balance behavior scores reflecting positive energy balance using the items on the Qualtrics survey administered.

Items used to estimate a high-sedentary behavior score included change in television watching, change in screen time, and change in sitting time. Items used to estimate a low-physical activity behavior score included change in walking time, change in vigorous physical activity, and change in moderate physical activity.

The low-healthy eating behavior score was calculated using responses on fruit and vegetable consumption as snacks or in general during meals. All behaviors included in development of a priori energy balance behavior scores have been extensively reported to contribute to positive energy balance or negative energy balance see Supplementary Material.

The α's for high-sedentary behavior score, low-physical activity behavior score, high-unhealthy eating behavior score, and low-healthy eating behavior score were 0.

Note that scores on low-physical activity behavior and low-healthy eating behavior were calculated such that higher scores reflected less physical activity and less fruit and vegetable consumption. We first conducted ANOVAs to test differences of health-risk behaviors between demographic groups.

We then calculated intercorrelations between energy balance behavior scores and health and psychological risk and protective factors.

We further conducted a Latent Profile Analysis LPA to identify and characterize patterns of health behavior change during the pandemic. LPA is a data-driven approach used to uncover relationships among individuals to create meaningful groups or classes of people based on the heterogeneity of their responses; these classes can then be characterized and compared to each other using important demographic, psychological, and behavioral factors Classes of people determined by LPA have been used to describe distinct differences in cognition and behavior among people with regard to a variety of physical and mental health phenomena, such as alcohol use, sleep, occupational stress, resilience, coping strategies etc.

In the current work, we used LPA to reveal different classes of people's health-risk behaviors during the COVID pandemic shelter-at-home. We then compared the classes on psychological, behavioral, and demographic qualities to provide comprehensive representations of various groups of people's characteristics, thoughts, and behaviors during the COVID pandemic shelter-at-home.

This analysis does not focus on the amount of change within one behavior but instead looks at patterns of change i. ANOVAs were conducted to evaluate differences of risk behaviors between demographic groups. Participants' scores for four energy balance behavior scores are presented for each demographic variable in Table 1.

Briefly, the score for increasing sedentary behavior was significantly higher among women vs. The score for low-physical activity was significantly higher among Asians vs.

The score for high-unhealthy eating was significantly higher among women vs. Table 1. Scores for four energy balance behavior categories by demographic profile of participants. Scale intercorrelations were calculated to highlight associations between psychological and health risk and health protective factors.

Correlations are shown in Table 2. Next, we conducted a LPA to characterize classes of participants' patterns of risky health behaviors during the COVID pandemic using composite variables for physical activity, sedentary behavior, healthy food consumption, and unhealthy food consumption.

The classes' patterns of endorsed risky health behaviors are shown in Figure 1. Figure 1. Average scores of engagement in obesogenic risk behaviors by latent classes. Class 3 is considered the General Low Risk Group; Class 4 is considered the General High-Risk Group.

Class 1 is the Medium General Risk, Medium Sedentary Risk Group, and Class 2 is the Medium General Risk, High Sedentary Risk Group. Examining the characteristics of participants in all risk profiles Table 3 , individuals in the highest risk class Class 4; Participants in the low-risk category Class 3; 5.

Classes 1 In terms of psychosocial risk factors, Class 2 differed from Class 1 in sleep patterns Class 2 participants reported waking up less alert despite reporting more hours of sleep , boredom, self-control, and mood.

Although people in these classes were similar in physical activity and engaged in a mixed pattern of healthy and unhealthy eating habits, they exhibited different patterns of positive mood, craving control, cravings, boredom, and self-control.

Demographic differences also emerged across groups. Participants in Classes 1 and 3 relatively lower risk were more likely to be male, married and White.

Table 3. Psychosocial risk factors across class determined by latent profile analysis. The primary purpose of this paper was to investigate the relationship between relevant psychological markers and energy balance-related behavior scores, during the COVID related shelter-in-place.

Whereas, having psychological traits such as greater general self-control, control over cravings, or positive mood was related to lower self-reported energy intake and energy expenditure during the lockdown. Individuals with the highest risk pattern reported having higher sleepiness, more boredom, less positive mood, and more cravings for sweet and savory foods.

Our hypothesis that self-reported change in boredom during the lockdown, a state like-psychological variable, may be related to dietary intake risk was based on prior research suggesting that high boredom increases the desire for and intake of unhealthy foods and snacks Our data support these findings by showing that boredom was related to the increased risk of consuming unhealthy foods energy-dense sweet and savory snacks, sugary drinks, etc.

and lowering healthy food intake fruits and vegetables during the pandemic. Boredom is shown to encourage people to seek sensation 52 ; hence, we speculate that exciting options, such as sugary and fatty foods, may have served as a potent distractor of self-regulation by providing intense appearance or taste.

As a result, people gravitate toward easier tasks that require less cognitive load, such as the use of smartphones, the internet, or online socializing 54 , 55 ; this may explain the relationship observed between increased sedentary behavior, low physical activity and boredom, in our dataset.

The relationship observed between self-reported sleepiness ratings, sleep duration, and diet quality in the current study confirms results from prior studies. We, and others, have previously shown that higher sleepiness 26 , 56 and reduced sleep duration 57 are both related to food cravings and intake of energy-dense savory and sugary foods that may manifest in positive energy balance.

The relationship of sleep time with sedentary activity is more complex, with long and short sleep durations both shown to impact sedentary behaviors in previous studies. In contrast, long sleep duration lowers daytime activity levels and increases screen-based sedentary behaviors These data suggest that the reported positive correlation between sleep duration and sedentary activity is possibly related to a decline in overall wake time activity.

We further speculate that lethargy after a long sleep duration and having less time available in the day may have added to increased sedentary behavior. It is equally possible that spending more sedentary time, especially in front of the screen, may reduce sleep quantity and quality Given the cross-sectional design of this study, it is difficult to determine the directionality of the relationship between sleep duration and sedentary behavior in our participants during the shelter-at-home.

Similar to the findings by Buckland et al. where lower craving control predicted high energy dense sweet and savory food intake during COVID lockdown, we also showed that greater control on food cravings, representing a state-like psychological characteristic, was related to unhealthy eating score Intense food craving is often accompanied with lower mood and anxiety levels, and commonly reported with high BMI Accordingly, we demonstrated that high craving control correlated with positive mood score and healthy food selection.

Our data also shows a relationship between craving control and low reduction in physical activity. Interestingly, physical activity interventions can reduce cravings for high-caloric foods as well as mood While we cannot confirm directionality in our cross-sectional data, it is possible that maintenance of high physical activity contributed to better mood and low boredom, thus supporting control over cravings.

In everyday life, general self-control, a trait psychological characteristic, is associated with positive weight management behaviors, including healthier eating, successful weight loss, and increased physical activity, as well as with better psychological well-being 65 — The current study extends previous research on the personal benefits of self-control by highlighting the potentially protective aspects of self-control during a time when typical lifestyles have been majorly disrupted—in the context of a global pandemic.

Because uncertainty increases the desire for indulgence 68 , having high self-control may buffer temptation engagement during COVID shelter-in-place. Notably, in this study, people who reported the least engagement in energy balance-related behaviors had the highest self-control.

Those with relatively higher self-control also reported feeling in control of their food cravings, had fewer cravings for sweet and for savory foods, believed that body weight is malleable, and had lower average BMI.

It could be that people who have higher self-control are better able to continue their established physical activity routines and habits of inhibiting unhealthy food consumption in times of uncertainty 69 , 70 and to initiate new lifestyle adjustments in the face of necessary change People with high self-control may also be adept at avoiding tempting situations 71 , 72 , which may happen frequently during shelter-in-place e.

In addition, people with higher self-control experienced several positive emotional benefits during shelter-in-place: on average, they felt less bored, reported higher positive mood, more alertness after waking, and less stress.

Being able to successfully navigate temptation, resolve self-control conflicts, and pursue their goals, even in an unpredictable time, likely has a beneficial effect on mental well-being Taken together, trait self-control may be a protective factor against the negative effects of COVID shelter-in-place.

One predictor of weight management behaviors is the belief that a person's body weight is malleable 29 — 31 , In contrast to previous work, however, people in the current study who were classified as engaging the least in energy balance-related behaviors vs.

people in the higher risk classes reported stronger beliefs that body weight is not malleable. Replicating previous correlational findings 30 , 74 , in the current study, participants' beliefs about weight malleability were unrelated to their BMI.

Surprisingly, people who had stronger entity beliefs about body weight reported less sedentary behavior and less unhealthy eating; beliefs about weight control were unrelated to physical activity risk and healthy eating risk.

One possible explanation for this finding might be that people who believed they can control their weight felt like they might be able to regain energy balance after the pandemic—that they could manage their weight well when they had the time and resources to do so. Counterintuitively, their health behaviors during the pandemic may have slipped because they thought they might be able to make up for it later.

Alternatively, it may be that self-efficacy—which is a mechanism by which beliefs about weight control influence health behaviors 29 , 74 —was interrupted during the COVID pandemic.

It could also be the case that during this unprecedented time, people may have generally low beliefs that if they were to experience setbacks in their weight management pursuits, they would be able to successfully cope with those challenges. Although we did not directly measure self-efficacy nor expectations of future success, people who reported having weaker incremental weight beliefs also reported lower positive mood, less control over their food cravings, higher cravings for sweet foods, less alertness after waking, and higher stress.

Participants' negative mood may signal to them that they are making poor progress on their goals and will subsequently be less successful in the future 75 , which may be indicative of their engagement with weight-management behaviors.

In our study, people with more positive mood had a lower risk of less physical activity and unhealthy eating. Along the same lines, feelings of control of one's food cravings predict lower risks of unhealthy and healthy eating. These negative psychological factors experienced during shelter-in-place may attenuate the otherwise positive effect that incremental beliefs usually have on weight management behaviors.

Given the heterogeneity in energy balance-related behaviors, an assessment of risk profile groups gave us a better insight into the unique characteristics of individuals who may be more prone to weight gain during the pandemic.

Not surprisingly, individuals with the highest risk not only engaged in all energy balance-related behaviors but also reported to have psychological and health markers known to promote obesity.

Although similar in risk level, we observed subtle but unique differences between the two moderate risk groups. The most striking difference between the two groups was sedentary behavior. As theorized by previous work, a complex interplay between personal circumstances, environmental variables, and social factors determines sedentary behavior A large percentage of high sedentary risk group Class 2 individuals belonged to a high-income bracket.

High income groups are more likely to hold sedentary jobs 77 and are known to engage in prolonged sedentary behavior, as compared to lower income groups. Occupational sitting and screen time, along with the closure of all outdoor avenues and added pressure of being always on when working from home, may have put the higher income group at higher risk.

We also noticed that a large percentage of adults in this group were married or living with a partner. While we did not measure it directly, there is a plausibility of higher perceived modeling of sedentary behavior in presence of a partner, especially if the partner spends more time engaged in screen time Additionally, perceived behavioral control is likely to be protective of sedentarism 79 , which was prevalent in the Class 2 risk group.

By contrast, studies also show that when it comes to sedentary behaviors, self-control beliefs may be ineffective in influencing the decision to be sedentary.

Rather it is the discriminant motivational structure, high access, and ease of use among people who wish to perform these behaviors This lack of motivation with high boredom and negative mood may have been the differentiating factor for sedentary behavior in the two groups during the pandemic.

The results of this study must be interpreted in light of several limitations. This study was cross-sectional and non-experimental; thus, causality and temporality cannot be inferred.

As such, we cannot conclude if reported alterations in behaviors truly lead to weight gain. Additionally, while there is evidence of behavior changes with body mass index status, due to the self-reported nature of height and weight data collected, we did not test the difference in health behaviors between BMI groups.

We also asked participants to report their perception of behavior change increased, decreased, remained the same , rather than asking them to report behaviors before and during the lockdown period and calculating the change score for each variable.

Moreover, a recent report demonstrated that perceptual increase in physical activity is driven by the amount of vigorous physical activity performed, suggesting that an increase in intensive physical activity is important for perceiving a change in one's physical activity In contrast, smaller changes may need to be sufficient for change to be perceived as such Thus, the self-reported change scores in our study may not be accurate.

Furthermore, with possible differences in perception of individual behavioral component of score categories, our aggregate scores for these categories may be subject to biases.

While pandemic related restrictions limited our ability to collect data on energy balance behaviors subjectively, the importance of using objective measures cannot be denied. Recall bias, especially with using non-validated tools, may confound self-reports reflecting a perceived rather than actual change behaviors during the lockdown This should be taken into consideration when interpreting our findings.

Additionally, while we did not disclose the specific purpose of the study to the participants, our results could also be driven by participant's expectation and not their actual behavior. With regards to the questionnaires, while validated instruments were used as possible, some necessary questions were developed by the investigators to capture the current unique environment.

Moreover, we did not use a validated tool for dietary intake, such as food frequency questionnaires. Thus, care should be taken to integrate these findings with the broader literature. For our psychological and health behavior constructs, some variables were contextual or state like, while some were trait like.

However, this should not have impacted our findings because whether it is a state like characteristic or trait like characteristic, we were interested in how it influenced energy-balance-related behaviors and how they differed between the risk classes. Moreover, despite the diversity and size of our sample, a convenience sampling approach was used, which may limit generalizability.

Furthermore, the degree of shelter-in-place guidelines and the number of COVID cases in participants' area of residence likely differed, creating differences in flexibility with stepping outside the house.

The time frame of data collection may have influenced our results as well. As such, at the time of data collection, although most states had implemented shelter-in-place guidelines, a few states were considering lifting the restrictions.

This one snapshot of time also assumes that thoughts and behaviors were static throughout the entire shelter-in-place time, which is likely an oversimplification. Altogether, this study describes state- and trait-like psychological factors that relate to energy balance-related behavior categories during the COVID shelter-at-home restrictions in the U.

Our analysis provides important insights into the complex interplay of factors related to risk of increasing unhealthy eating and sedentary activities and decreasing healthy eating and physical activity. These results also contribute to improving our understanding of the patterns of risk groups and their unique characteristics, specifically highlighting that the lockdown did not adversely impact energy balance behaviors in all individuals.

The numbers within the equations for the EER were derived from measurements taken from a group of people of the same sex and age with similar body size and physical activity level.

These standardized formulas are then applied to individuals whose measurements have not been taken, but who have similar characteristics in order to estimate their energy requirements. EER values are different for children, pregnant or lactating women, and for overweight and obese people.

Also, remember the EER is calculated based on weight maintenance, not for weight loss or weight gain. Source: US Department of Agriculture. Source: Institute of Medicine. Fiber, Fat, Fatty Acids, Cholesterol, Protein, and Amino Acids.

September 5, The amount of energy you expend every day includes not only the calories you burn during physical activity, but also the calories you burn while at rest basal metabolism , and the calories you burn when you digest food.

The sum of caloric expenditure is referred to as total energy expenditure TEE. breathing, heartbeat, liver and kidney function while at rest. The basal metabolic rate BMR is the amount of energy required by the body to conduct its basic functions over a certain time period.

Unfortunately, you cannot tell your liver to ramp up its activity level to expend more energy so you can lose weight.

BMR is dependent on body size, body composition, sex, age, nutritional status, and genetics. People with a larger frame size have a higher BMR simply because they have more mass.

Muscle tissue burns more calories than fat tissue even while at rest and thus the more muscle mass a person has, the higher their BMR. As we get older muscle mass declines and thus so does BMR.

Nutritional status also affects basal metabolism. Caloric restriction, as occurs while dieting, for example, causes a decline in BMR. This is because the body attempts to maintain homeostasis and will adapt by slowing down its basic functions to offset the decrease in energy intake.

Body temperature and thyroid hormone levels are additional determinants of BMR. The other energy required during the day is for physical activity. Depending on lifestyle, the energy required for this ranges between 15 and 30 percent of total energy expended.

The main control a person has over TEE is to increase physical activity. Calculating TEE can be tedious, but has been made easier as there are now calculators available on the Web. TEE is dependent on age, sex, height, weight, and physical activity level.

The equations are based on standardized formulas produced from actual measurements on groups of people with similar characteristics. To get accurate results from web-based TEE calculators, it is necessary to record your daily activities and the time spent performing them.

Interactive com offers an interactive TEE calculator. In the last few decades scientific studies have revealed that how much we eat and what we eat is controlled not only by our own desires, but also is regulated physiologically and influenced by genetics.

The hypothalamus in the brain is the main control point of appetite. It receives hormonal and neural signals, which determine if you feel hungry or full.

Hunger is an unpleasant sensation of feeling empty that is communicated to the brain by both mechanical and chemical signals from the periphery. Conversely, satiety is the sensation of feeling full and it also is determined by mechanical and chemical signals relayed from the periphery.

This results in the conscious feeling of the need to eat. Alternatively, after you eat a meal the stomach stretches and sends a neural signal to the brain stimulating the sensation of satiety and relaying the message to stop eating.

The stomach also sends out certain hormones when it is full and others when it is empty. These hormones communicate to the hypothalamus and other areas of the brain either to stop eating or to find some food.

Fat tissue also plays a role in regulating food intake. Fat tissue produces the hormone leptin, which communicates to the satiety center in the hypothalamus that the body is in positive energy balance.

Alas, this is not the case. In several clinical trials it was found that people who are overweight or obese are actually resistant to the hormone, meaning their brain does not respond as well to it.

Dardeno, T. et al. Therefore, when you administer leptin to an overweight or obese person there is no sustained effect on food intake. Nutrients themselves also play a role in influencing food intake. The hypothalamus senses nutrient levels in the blood. When they are low the hunger center is stimulated, and when they are high the satiety center is stimulated.

Furthermore, cravings for salty and sweet foods have an underlying physiological basis. Both undernutrition and overnutrition affect hormone levels and the neural circuitry controlling appetite, which makes losing or gaining weight a substantial physiological hurdle.

Genetics certainly play a role in body fatness and weight and also affects food intake. Children who have been adopted typically are similar in weight and body fatness to their biological parents. Moreover, identical twins are twice as likely to be of similar weights as compared to fraternal twins.

The scientific search for obesity genes is ongoing and a few have been identified, such as the gene that encodes for leptin.

Recall Fat-burning foods the macronutrients hbits consume Energt either converted Energy balance and dietary habits energy, habigs, or used Energy balance and dietary habits synthesize macromolecules. When you are in dieatry positive energy balance the excess nutrient energy will be stored or used to grow e. Energy Dangers of untreated hyperglycemia is achieved when Energy balance and dietary habits of energy is equal to energy expended. Weight can be thought of as a whole body estimate of energy balance; body weight is maintained when the body is in energy balance, lost when it is in negative energy balance, and gained when it is in positive energy balance. In general, weight is a good predictor of energy balance, but many other factors play a role in energy intake and energy expenditure. Some of these factors are under your control and others are not. Let us begin with the basics on how to estimate energy intake, energy requirement, and energy output. Self-reported weight gain during the COVID shelter-at-home Mushroom Health Studies raised Energy balance and dietary habits for weight dietzry as the pandemic continues. We Natural weight loss for beginners to Enwrgy Energy balance and dietary habits relationship of psychological and health markers hbaits energy balance-related behaviors during the EEnergy extended home confinement. Ratings for stress, boredom, annd, sleep, Boost immunity naturally, and beliefs about hhabits control were Energt from haits, adults using a questionnaire between April 24th—May 4th,while COVID associated shelter-in-place guidelines were instituted across the US. We calculated four energy balance behavior scores physical activity risk index, unhealthy eating risk index, healthy eating risk index, sedentary behavior indexand conducted a latent profile analysis of the risk factors. We examined psychological and health correlates of these risk patterns. Having greater self-control, control over cravings, or positive mood was related to lowering all aspects of energy intake and energy expenditure risks. Psychological and health variables may have a significant role to play in risk behaviors associated with weight gain during the COVID related home confinement.

Ich meine, dass Sie den Fehler zulassen. Geben Sie wir werden es besprechen. Schreiben Sie mir in PM, wir werden reden.

Bemerkenswert, diese lustige Mitteilung

Ich bin endlich, ich tue Abbitte, aber diesen ganz anderes, und nicht, dass es mir notwendig ist.