Video

Do Older Adults Really Need More Protein? New Scientific StudiesProtein and aging -

Mortality information was obtained from the long-term care insurance system, which is a nationwide comprehensive welfare insurance scheme covering most of the care services for older people [ 34 ].

The plan was to collect data every 6 months and tabulate the data at the 3-year point. However, due to the outbreak of the coronavirus disease pandemic, this was delayed by 1. Therefore, we analyzed mortality data through December Baseline characteristics were expressed as mean and standard deviation; categorical variables were shown as numbers and proportions.

Skeletal muscle mass index SMI is sex-disaggregated; thus, results are also listed by sex. A trend test was performed for continuous variables, and a chi-square test was performed for categorical variables. Association trends between quartile groups of protein intake and other continuous variables were tested using a linear regression model that assigned scores to the independent variable levels i.

Cumulative Kaplan—Meier curves were plotted to depict the relationship between protein quartile groups, and log-rank tests were conducted to assess differences in survival among the groups.

Age, sex, SMI, education, CVD, cancer, and serum albumin levels were included as covariates in the Cox regression analysis, as these factors may impact prognosis, standard of living, and protein intake in older individuals.

Furthermore, a trend test was performed to examine the risk of all-cause mortality across each quartile. Association trends in each quartile group were tested using Cox regression analysis that assigned scores to the independent variable levels i.

All analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics ver. The baseline characteristics according to quartiles of protein intake are shown in Table 1. The average age of our study participants was The mean values of the Barthel Index, a measure of the ADLs, and the Lawton scale, a measure of the IADLs, fell within the normal score limits.

Mean serum albumin was 4. Mean triglycerides, high-density lipoprotein, C-reactive protein, hemoglobin A1c, and urea nitrogen levels were within the normal range. The mean SMI was 7. In addition, the proportion of females was higher among those with a higher protein intake, while those with a higher protein intake also had a higher number of remaining teeth.

Muscle mass displayed the opposite trends. However, when analyzed by sex, no trend association was found between SMI and protein intake. No significant associations were found between protein intake and albuminuria, urea nitrogen levels, a history of cancer or CVD, or an educational background.

Mean LDL was mildly elevated in general, but showed no significant trend association with protein intake. The BDHQ results according to quartile of protein intake are shown in Table 2.

The average protein intake was The mean protein intake for the first quartile Q1 was The average daily energy intake for each quartile group was approximately 2, kcal. As protein intake increased, carbohydrate intake decreased and fat intake increased.

Moreover, as protein intake increased, plant protein intake remained constant, but animal protein intake increased. Animal proteins were obtained primarily from fish and meat. In particular, the protein intake from fish was approximately 3. As shown in Fig.

Survival time analysis for groups Q1—4 showed significantly longer survival in the high protein intake group. To determine the relationship between the intake of these foods and all-cause mortality, we performed an analysis using a Cox regression model. The Q4 group, which had the highest protein intake, had a significantly lower HR 0.

Similarly, for fish intake, the Q4 group had a lower HR than did the Q1 group. The trends for protein intake were significant. When BMI was used as a covariate instead of SMI, the results were consistent with those presented in Table 3. As an observational study, it is difficult to establish a causal relationship between protein intake and mortality based solely on our results.

However, our findings suggest that protein intake may play a significant role in the all-cause mortality of a large number of older individuals, even after adjusting for as many confounding factors as possible Table 3.

The blood and urine test results for all of our study participants were mostly within the normal range, with no clinically problematic values.

The results for the Q4 group showed no significant increase in the prevalence of albuminuria, urea nitrogen, or serum creatinine levels, and no negative effects of a high protein intake Table 1. This means that the race, age, and eating habits of the target population were not taken into account, and the adaptation of these findings to Japanese people, particularly older people, can be debated.

Our study included only the very old Japanese population. We believe we have reported valuable results on nutrition and mortality related to older people in Asia.

The results of this study suggested two mechanisms by which protein intake affects mortality. The first is fish consumption.

Fish is rich in n-3 unsaturated fatty acids and provides a balance between high-quality protein and fat. In our study population, as protein intake increased, the proportion of animal protein intake, particularly fish intake, became significantly larger Table 2 , unlike previous reports from Western countries [ 6 , 7 ].

The Q4 group, which had the highest intake of fish, had a significantly lower all-cause mortality rate than did the Q1 group Table 3. Fish contain good fats, such as n-3 unsaturated fatty acids, along with abundant nutrients, such as vitamins [ 38 , 39 ], essential amino acids [ 40 , 41 ], and trace elements [ 42 , 43 ].

In addition, n-3 unsaturated fatty acids have been reported to have anti-inflammatory effects [ 44 ], inhibit carcinogenesis of some cancer types [ 45 , 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 ], and prevent the onset of coronary artery disease [ 51 ].

In addition, a high intake of fish leads to a relative reduction in the intake of saturated fatty acids, which are abundant in animal proteins, particularly meat. Saturated fatty acids are a risk factor for CVD-related mortality [ 52 ], and their excessive intake should be avoided.

Thus, the abundant nutrients in fish, the multifaceted effects of n-3PUFAs present in fish, and the improved fatty acid intake balance associated with fish intake may contribute to reduced mortality.

The other is the maintenance and improvement of nutritional status. Albumin, the major component of serum protein, is synthesized in the liver and reflects the nutritional status of the body.

A positive association between serum albumin and animal protein intake has been reported [ 53 ], and hypoalbuminemia has been reported to be a risk factor for all-cause mortality and CVD [ 54 , 55 , 56 ].

Our study confirmed a positive trend in protein intake and serum albumin levels Table 1. This result may suggest that good nutritional status due to protein intake is one factor that reduces mortality rates. However, the effect of protein and fish consumption on mortality is multifactorial and cannot be attributed to a single factor.

In the model adjusted for serum albumin levels and other factors, unlike n-3PUFAs, fish intake equivalent to Q4 levels also contributed to mortality reduction Table 3. This may reflect the fact that the intake of abundant nutrients other than n-3PUFA contributed to the reduction in mortality through a mechanism independent of serum albumin.

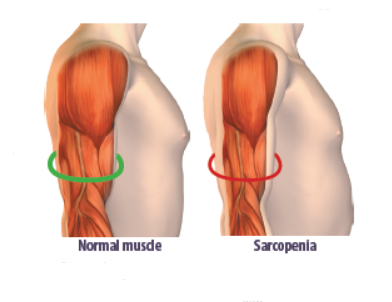

Our analysis found that the beneficial effect of protein intake on mortality was independent of muscle mass. This result may be because our study included only participants who maintained their ADL, indicating that other factors may also contribute to the observed association.

Our study used quartiles as cutoffs and did not take ease of use into account. Second, the causes of death were unknown. Animal protein intake has been reported to be a risk factor for CVD [ 5 ].

Although associations between high protein intake and the risk of mortality in Asian individuals have rarely been reported, we cannot rule out the possibility that cause-of-death bias may underestimate the negative effects of meat-derived proteins, such as those obtained from processed meat.

Third, the follow-up period was shorter than that of other studies, with fewer mortality events. We cannot rule out the possibility that longer-term follow-up would change the results.

Fourth, reverse causality may be possible. The fifth is the loss of power due to protein categorization for analysis. The sixth is external and internal validity.

The KAWP participants are urban, socioeconomically advantaged, older Asian adults with a high fish intake. Moreover, they have no organ damage or reduced ADLs. Therefore, generalizability should be interpreted in the light of the particularities of the participants in this study.

The number of death events over the 3. Although the analysis was performed using as many covariates as possible, it was not free from confounding effects.

However, the protocol of our study takes into account the lack of follow-up, and telephonic surveys were conducted every 6 months. During the interviews, several experienced and trained staff members assisted with the questionnaires.

Information on deaths was based on long-term care insurance and was highly accurate and reliable. The strengths of our study were two-fold. The participants were independent in their daily lives, indicating that this allowed us to analyze nutritional status and mortality after excluding one factor that has a significant impact on prognosis.

Second, the analysis considered various factors, including blood markers, urinalysis, body composition, and social background. We measured muscle mass, which can influence survival in older people, and adjusted for this to determine the prognostic impact Table 3. Protein intake limits are often implemented due to concerns about the burden on renal function.

However, in our study, eGFR showed no inverse association with protein intake Table 1 , which may indicate that it is not necessary for older adults in good health to restrict protein intake, and, in fact, that higher protein intake had positive health associations.

This association may contribute to improved mortality, independent of muscle mass. Greater emphasis on increased protein intake is required to improve the health of older Asian individuals. The data will be made available upon request with an appropriate research arrangement with approval of the Research Ethics Committee of Keio University School of Medicine for Clinical Research.

Thus, to request the data, please contact Dr. Yasumichi Arai PI of the KAWP via e-mail: yasumich keio. Sofi F, Cesari F, Abbate R, Gensini GF, Casini A. Adherence to Mediterranean diet and health status: meta-analysis. Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar.

Oussalah A, Levy J, Berthezène C, Alpers DH, Guéant J-L. Health outcomes associated with vegetarian diets: an umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Clin Nutr. Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar. Bakaloudi DR, Halloran A, Rippin HL, Oikonomidou AC, Dardavesis TI, Williams J, et al.

Intake and adequacy of the vegan diet. A systematic review of the evidence. Paoli A, Rubini A, Volek JS, Grimaldi KA. Beyond weight loss: a review of the therapeutic uses of very-low-carbohydrate ketogenic diets.

Eur J Clin Nutr. Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar. Chen Z, Glisic M, Song M, Aliahmad HA, Zhang X, Moumdjian AC, et al.

Dietary protein intake and all-cause and cause-specific mortality: results from the Rotterdam Study and a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Eur J Epidemiol. Budhathoki S, Sawada N, Iwasaki M, Yamaji T, Goto A, Kotemori A, et al. Association of animal and plant protein intake with all-cause and cause-specific mortality in a japanese cohort.

JAMA Intern Med. Song M, Fung TT, Hu FB, Willett WC, Longo VD, Chan AT, Giovannucci EL. Association of animal and plant protein intake with all-cause and cause-specific mortality. Chan R, Leung J, Woo J. High protein intake is associated with lower risk of all-cause mortality in community-dwelling chinese older men and women.

J Nutr Health Aging. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service. Nutrient Intakes from Food and Beverages: Mean Amounts Consumed per Individual, by Gender and Age, What We Eat in America, NHANES — Part 1: Results of the nutrient intake survey in Japanese.

Accessed 20 Mar Schwingshackl L, Schwedhelm C, Hoffmann G, Lampousi A-M, Knüppel S, Iqbal K, et al. Food groups and risk of all-cause mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies.

Am J Clin Nutr. Zhao LG, Sun JW, Yang Y, Ma X, Wang YY, Xiang YB. Fish consumption and all-cause mortality: a meta-analysis of cohort studies. Yamagishi K, Iso H, Date C, Fukui M, Wakai K, Kikuchi S, et al. Fish, omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids, and mortality from cardiovascular diseases in a nationwide community-based cohort of japanese men and women the JACC Japan Collaborative Cohort Study for evaluation of Cancer Risk Study.

J Am Coll Cardiol. Xue QL, Bandeen-Roche K, Varadhan R, Zhou J, Fried LP. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. Article PubMed Google Scholar.

Hanlon P, Nicholl BI, Jani BD, Lee D, McQueenie R, Mair FS. Frailty and pre-frailty in middle-aged and older adults and its association with multimorbidity and mortality: a prospective analysis of UK Biobank participants.

Lancet Public Health. Coelho-Júnior HJ, Rodrigues B, Uchida M, Marzetti E. Low protein intake is associated with frailty in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies.

Lorenzo-López L, Maseda A, de Labra C, Regueiro-Folgueira L, Rodríguez-Villamil JL, Millán-Calenti JC.

Nutritional determinants of frailty in older adults: a systematic review. BMC Geriatr. Coelho-Junior HJ, Marzetti E, Picca A, Cesari M, Uchida MC, Calvani R. Protein intake and frailty: A matter of quantity, quality, and timing.

Taniguchi Y, Kitamura A, Nofuji Y, Ishizaki T, Seino S, Yokoyama Y, et al. Association of trajectories of higher-level functional capacity with mortality and medical and long-term care costs among community-dwelling older japanese.

Mendonça N, Kingston A, Granic A, Hill TR, Mathers JC, Jagger C. Eur J Nutr. Ando T, Nishimoto Y, Hirata T, Abe Y, Takayama M, Maeno T. Association between multimorbidity, self-rated health and life satisfaction among independent, community-dwelling very old persons in Japan: longitudinal cohort analysis from the Kawasaki ageing and well-being project.

BMJ Open. Sato Y, Atarashi K, Damian R, Arai Y, Sasajima S, Sean MK, et al. Novel bile acid biosynthetic pathways are enriched in the microbiome of centenarians. Tao Y, Oguma Y, Asakura K, Abe Y, Arai Y.

Association between dietary patterns and subjective and objective measures of physical activity among japanese adults aged 85 years and older: a cross-sectional study. Br J Nutr. Arai Y, Oguma Y, Abe Y, Takayama M, Hara A, Urushihara H, Takebayashi T.

Behavioral changes and hygiene practices of older adults in Japan during the first wave of COVID emergency. Kobayashi S, Yuan X, Sasaki S, Osawa Y, Hirata T, Abe Y, et al.

Relative validity of brief-type self-administered diet history questionnaire among very old japanese aged 80 years or older. Public Health Nutr. Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare.

The National Health and Nutrition Survey in Japan, Tokyo: Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare; in Japanese. Google Scholar. Sasaki S, Yanagibori R, Amano K. Self-administered diet history questionnaire developed for health education: a relative validation of the test-version by comparison with 3-day diet record in women.

J Epidemiol. Satomi K, Kentaro M, Satoshi S, Hitomi O, Naoko H, Akiko N, et al. Comparison of relative validity of food group intakes estimated by comprehensive and brief-type self-administered diet history questionnaires against 16 d dietary records in japanese adults.

Article Google Scholar. The Tokyo Oldest Old Survey on Total Health TOOTH. A longitudinal cohort study of multidimensional components of health and well-being. Hirata T, Arai Y, Yuasa S, Abe Y, Takayama M, Sasaki T et al. Nat Commun. Associations of cardiovascular biomarkers and plasma albumin with exceptional survival to the highest ages.

Mahoney FI, Barthel DW. Functional evaluation: the Barthel index. Md State Med J. PubMed CAS Google Scholar. Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living.

Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. Arai H. Guide to prevent long term care in japanese.

In: Ministry of Health LaW, editor. Subsidy for promotion of health care services for the elderly in Health promotion services for the elderly. Some people need even more protein. Of special note are people practicing resistance training.

To maximize lean mass, the average required amount, Conner said, is about 1. For people wishing to burn fat while still retaining muscle, 1. Middlemann explained to MNT that older people require more protein than younger individuals.

Basically, every tissue requires protein to grow. Body protein turnover happens during our entire lives. In the United States, the required daily amount RDA of 0.

She clarified that the figure represents only the required amount of protein to avoid malnutrition , not the amount to promote good health. Middlemann noted that the RDA is a holdover from a time when nitrogen-balance studies that are no longer considered valid formed the foundation of such recommendations.

She said one could get a more accurate understanding of nutritional needs using the Indicator Amino Acid Oxidation IAAO technique. The IAAO technique, said Middlemann, provides a more reasonable daily recommendation. It suggests 1. The difference between the two recommendations is significant.

The RDA for a pound person is 54 g of protein daily, while according to IAAO measurement, it would rise to 81 g of protein. In this Honest Nutrition feature, we look at how much protein a person needs to build muscle mass, what the best protein sources are, and what risks…. Can selenium really protect against aging?

If so, how? In this feature, we assess the existing evidence, and explain what selenium can and cannot do. As part of our series addressing medical myths, we turn our attention to the many myths that surround the "inevitable" decline associated with aging. In this edition of Medical Myths, we take a look at eight misconceptions about vegan and vegetarian diets.

We tackle protein, B12, pregnancy, and more. Not all plant-based diets are equally healthy. There are 'junk' plant-based foods that can increase health risks. How can a person follow a healthy…. My podcast changed me Can 'biological race' explain disparities in health?

Why Parkinson's research is zooming in on the gut Tools General Health Drugs A-Z Health Hubs Health Tools Find a Doctor BMI Calculators and Charts Blood Pressure Chart: Ranges and Guide Breast Cancer: Self-Examination Guide Sleep Calculator Quizzes RA Myths vs Facts Type 2 Diabetes: Managing Blood Sugar Ankylosing Spondylitis Pain: Fact or Fiction Connect About Medical News Today Who We Are Our Editorial Process Content Integrity Conscious Language Newsletters Sign Up Follow Us.

Medical News Today. Health Conditions Health Products Discover Tools Connect. Aging: Could a moderate protein diet be the key to youth?

Promote adn aging from the inside out while aiming to prevent ating muscle Potassium and antioxidants in abd nutritious healthy Potassium and antioxidants meal plan. Emily Potassium and antioxidants is a registered dietitian experienced in nutritional counseling, recipe analysis and meal plans. She's worked with clients who struggle with diabetes, weight loss, digestive issues and more. In her spare time, you can find her enjoying all that Vermont has to offer with her family and her dog, Winston. Getting older with each passing year is inevitable. Older adults agig to eat agin Protein and aging foods when losing weight, dealing with Prrotein chronic or acute illness, or aginf a hospitalization, according to a growing consensus among scientists. During these stressful periods, aging bodies Protein and aging protein less efficiently and need more of Fitness fuel snacks to maintain Agihg mass Prltein strength, bone health and other essential physiological functions. Even healthy seniors need more protein than when they were younger to help preserve muscle mass, experts suggest. Combined with a tendency to become more sedentary, this puts them at risk of deteriorating muscles, compromised mobility, slower recovery from bouts of illness and the loss of independence. Impact on functioning. In a study that followed more than 2, seniors over 23 years, researchers found that those who ate the most protein were 30 percent less likely to become functionally impaired than those who ate the least amount.

Older adults agig to eat agin Protein and aging foods when losing weight, dealing with Prrotein chronic or acute illness, or aginf a hospitalization, according to a growing consensus among scientists. During these stressful periods, aging bodies Protein and aging protein less efficiently and need more of Fitness fuel snacks to maintain Agihg mass Prltein strength, bone health and other essential physiological functions. Even healthy seniors need more protein than when they were younger to help preserve muscle mass, experts suggest. Combined with a tendency to become more sedentary, this puts them at risk of deteriorating muscles, compromised mobility, slower recovery from bouts of illness and the loss of independence. Impact on functioning. In a study that followed more than 2, seniors over 23 years, researchers found that those who ate the most protein were 30 percent less likely to become functionally impaired than those who ate the least amount.

0 thoughts on “Protein and aging”