Video

How to Slow Cognitive Decline - Dr. Peter Attia \u0026 Dr. Andrew HubermanPolyphenols and cognitive function -

Episodic memory primary outcome measure , working memory, accuracy of attention, and visuospatial learning were evaluated by calculating the mean percentage of the cognitive tasks detailed in Supplementary Table S2.

The speed of information processing was assessed by calculating the mean reaction time of cognitive tasks detailed in Supplementary Table S2.

It contains 75 items where scores are calculated for an overall global score and two index scores comprising the behavioral regulation index and the metacognition index Roth et al.

The online version of the BRIEF-A was completed onsite at weeks 0, 12, and Lower scores on the BRIEF-A indicate better executive function. The CFQ is a self-report item questionnaire that assesses the frequency of cognitive difficulties Broadbent et al.

The CFQ has sound psychometric properties Bridger et al. The CASP is a item measure of well-being developed for older people Hyde et al. Questions are rated on a 4-point scale ranging from never to often, with higher scores suggesting better well-being.

In studies on older adults with dementia, and community-dwelling older-age adults, the CASP had good psychometric properties Sim et al. Consumed foods and liquids were entered into Nutrilog, 2 and the mean daily polyphenol intake was estimated based on the following food databases: Nuttab -Release 1, Mc Cance, Nuttab , and USDA.

Participants were also requested to contact researchers if they experienced any adverse effects. An a priori power analysis was undertaken to estimate the required sample size based on a single outcome variable and was powered based on episodic memory.

Based on the results of this study, a power calculation with a medium effect size of 0. Outcome analyses were conducted using intention-to-treat ITT , with all participants retained in originally assigned groups.

Time points considered for each measure comprised: 1 COMPASS measures weeks 0, 12, and 24 comprising episodic memory primary outcome measure , speed of information processing, accuracy of attention, 2 BRIEF-A global score weeks 0, 12, and 24 , 3 CASP total score weeks 0, 4, 8, 12, 16, 20, and 24 , and 4 CFQ total score weeks 0, 4, 8, 12, 16, 20, and The COMPASS groupings are consistent with other studies that have administered the COMPASS as an outcome measure Kennedy et al.

As an exploratory analysis, further analyses using GLMM were conducted on the BRIEF-A behavioral regulation index and metacognition index. Random intercepts were utilized in each GLMM model, and covariates of age, sex, baseline BMI, educational level, average energy intake, and average dietary polyphenol intake were included as fixed effects.

Where applicable, gamma with log link function and normal with identity link function target distributions were used. Appropriate covariance structures were used to model correlation associated with repeated time measurements in gamma models. Robust estimations were used to handle any violations of model assumptions.

Intervention group differences at time points were assessed using simple contrasts. As a measure of visuospatial learning, a visit x trial x group, repeated-measures ANCOVA was performed on the displacement scores trials 1 to 5 on the location learning task covariates of age, sex, baseline BMI, educational level, average energy intake, and average dietary polyphenol intake.

Moreover, a trial x group, repeated-measures ANCOVA was conducted at each visit weeks 0, 12, and 24 to examine differences in visuospatial learning at each visit.

Data from participants were included in the location learning analyses if data were obtained at week 12 [last observation carried forward from week 12 for missing values]. As the location learning displacement scores were not normally distributed, the data were winsorized, where scores greater than 3 standard deviations from the mean were replaced with the highest score that fell below the criterion of 3 standard deviations from the mean.

Due to the exploratory nature of this trial, there was no adjustment to the value of p for multiple testing. As detailed in Figure 1 , from people who completed the initial online screening questionnaire, did not fulfill the eligibility criteria, and 13 withdrew consent to participate in the study.

Details of participant baseline scores and background information of the total sample are detailed in Table 1. There were no other statistically significant time x group interactions on other COMPASS cognitive tasks. Capsule bottles with remaining capsules were returned at the week assessment, and participants completed a daily medication monitoring phone application.

To assess the effectiveness of condition concealment during the study, participants predicted at the end of the trial their condition allocation i. The frequency of self-reported adverse reactions is included in Table 5.

No serious adverse reactions were reported by participants, and a similar frequency of adverse reactions was reported in both groups.

Five participants withdrew from the trial due to a moderate severity of self-reported adverse reactions associated with capsule intake. However, there were no significant between-group differences in episodic memory, working memory, or accuracy in attention.

This was specifically characterized by a greater improvement in the Metacognition index. However, there were no between-group differences in changes in other self-report measures of cognitive abilities or quality of life.

In fact, study dropouts were more common in the placebo group, with many participants citing adverse reactions from the capsules as the reason for withdrawal from the study.

In recent systematic reviews examining the impact of grape Bird et al. Moreover, in a systematic review of berry-based supplements and foods, it was reported that they may have beneficial effects on resting brain perfusion, cognitive function, memory performance, executive functioning, processing speed, and attention indices Bonyadi et al.

However, substantial differences in the clinical trials make robust conclusions difficult. Overall, these findings may have important implications for the progression of MCI. In a meta-analysis of 7 studies, it was confirmed that reaction time is slower in people with MCI, and its slowing may be an early sign of AD Andriuta et al.

Moreover, it has been demonstrated that performance on the location learning task is worse in people with AD compared with MCI, indicating that this measure could discriminate between MCI and AD Kessels et al.

In a study on the BRIEF-A, adults with MCI and subjective cognitive complaints reported significant difficulties with selective aspects of executive functioning relative to healthy controls despite clinically normal performance on several neuropsychological tests of executive function.

These findings suggest that the BRIEF-A may be sensitive to subtle changes in executive function Rabin et al. Although not measured in this study, the informant-reported BRIEF-A also seems to provide a reliable indicator of cognitive deficits in older adults Scholz and Donders, It is important to note that in this study, several statistically significant improvements were identified in the placebo group over time.

This was demonstrated by improvements in immediate and delayed word recall, choice reaction time, and reaction time on the Stroop task. Moreover, there was a statistically significant reduction in the CFQ score over time in the placebo group, but no significant changes were observed in the remaining self-report measures BRIEF-A and CASP.

These results suggest that practice and placebo responses partly accounted for changes observed over time in participants, but this did not occur in all tasks. Some of the practice effects may have been minimized in the study as computer-based tasks were only completed on 3 occasions over a 6-month period.

Additionally, it is possible that the re-administration of the cognitive tasks masked some of the performance deteriorations that might be observed in people with MCI over time.

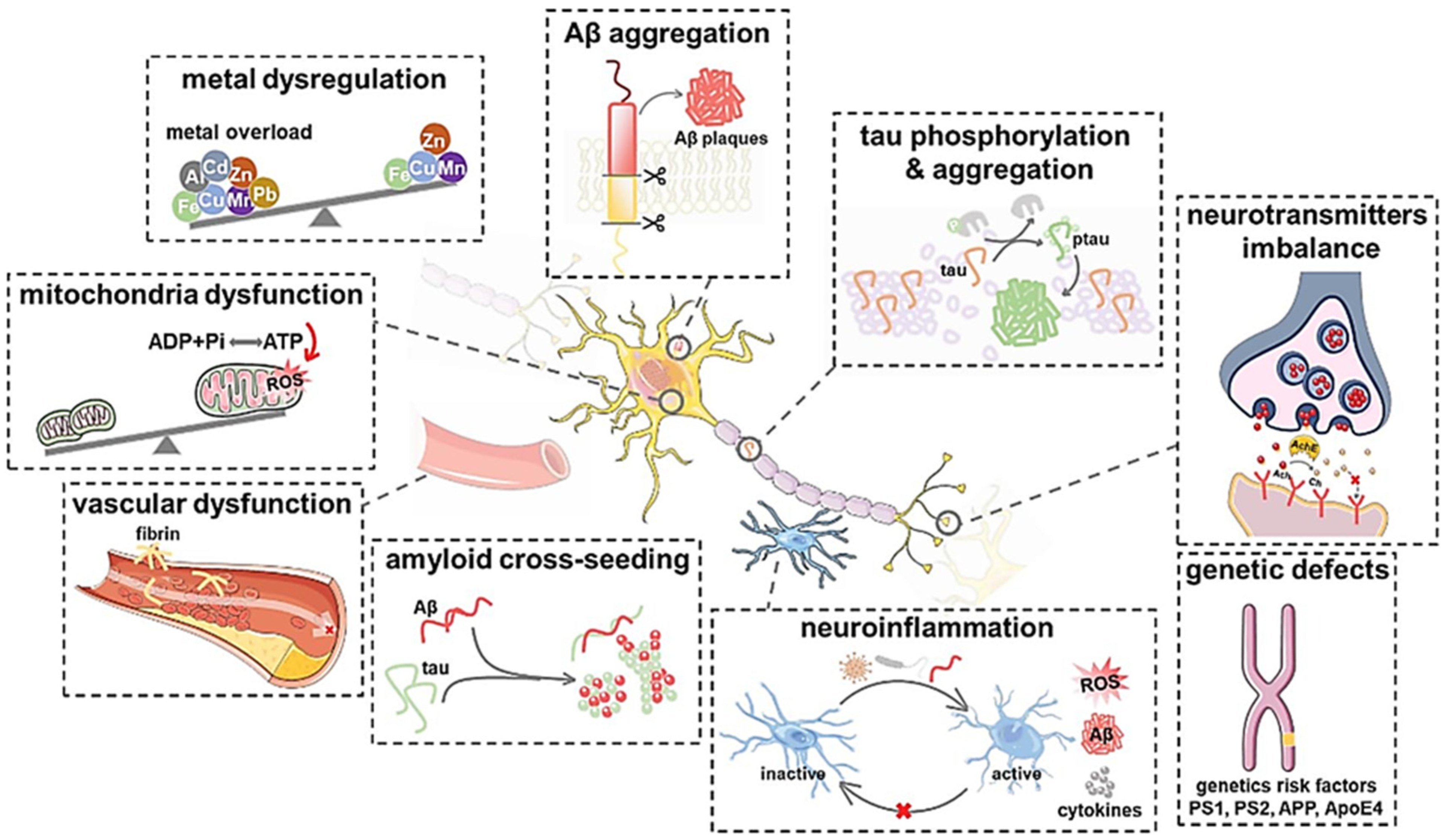

How grapes and blueberries affect cognitive functioning requires further investigation, although several mechanisms are speculated. In preclinical and in vitro trials, blueberry supplementation reversed neuronal aging attributed to a reduction in oxidative stress Joseph et al.

Blueberries may also lower neuroinflammation Shukitt-Hale et al. Preclinical trials have also demonstrated that grapes can alleviate age-related reduction of hippocampal neurogenesis and synaptogenesis Rastegar-Moghaddam et al.

All in all, these studies demonstrate that blueberries and grapes may provide cognitive benefits via their antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and neuroprotective effects; upregulation of neuronal signaling proteins; and stimulation of neurogenesis.

However, as these biological actions were not investigated in this study, these mechanisms remain speculative. Despite some positive results from the study, further research is required to validate and expand upon the current findings. Moreover, identifying populations that may realize greater benefits from supplementation will be important.

Possibilities include younger people, adults with early and mild MCI or subjective memory complaints, or people consuming a diet low in polyphenols. Even though in this study, the habitual intake of dietary polyphenols did not influence treatment outcomes, more comprehensive dietary assessments may be required to provide a more valid measure of long-term dietary intake.

Objective outcome measures and more comprehensive and sensitive neuropsychological assessments will also help to substantiate the results from self-report and computer-based cognitive tasks.

These include measuring blood markers of oxidative stress, inflammation, and neurogenesis, and neural imaging to identify changes in brain centers associated with memory and cognitive performance. A more comprehensive assessment of MCI will also be important, as MCI in this study was diagnosed using the telephone version of the MoCA.

However, no between-group differences in other cognitive domains were identified, including episodic memory the primary outcome measure. The preliminary positive results of this unique polyphenol-rich extract require further investigation in robust clinical trials.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation. The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by National Institute of Integrative Medicine Human Research Ethics Committee.

DG, CP, LP, and AL designed the research. AL and SS conducted the research. AL and PD analyzed the data. AL, SS, CP, LP, DG, VP, and PD were involved in writing the paper. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

The funder was not involved in data collection, interpretation of data, or the decision to submit it for publication. AL is the managing director of Clinical Research Australia, a contract research organization that has received research funding from nutraceutical companies.

AL has also received presentation honoraria from nutraceutical companies. SS is an employee of Clinical Research Australia and declares no other conflicts of interest. PD and VP declare no conflicts of interest. All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers.

Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher. Andriuta, D. Is reaction time slowing an early sign of Alzheimer's disease? A meta-analysis. doi: PubMed Abstract CrossRef Full Text Google Scholar.

Bensalem, J. Polyphenols from grape and blueberry improve episodic memory in healthy elderly with lower level of memory performance: a Bicentric double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical study. A Biol. Polyphenol-rich extract from grape and blueberry attenuates cognitive decline and improves neuronal function in aged mice.

J Nutr. Dietary polyphenol supplementation prevents alterations of spatial navigation in middle-aged mice. One previous literature has also suggested that combing specific polyphenols could be more relevant for brain fitness than a single supplement of polyphenol subclasses Thus, identification of synergism between polyphenols and other nutritions becomes an area of interest.

On the other hand, diverse formulations have been produced to enhance the oral bioavailability of polyphenols. When dietary supplementation of polyphenols is regarded as a novel therapeutic approach, its poor bioavailability needs to be overcome.

The studies in this review are concentrated in non-dementia human subjects, resulting in a modest number of articles and inconsistent results exist.

Methodological aspects must be considered carefully. With regard to the majority of observational studies, assessment of polyphenol intake levels tends to be not accurate enough as a result of under- or overestimation of food consumption from self-reports and differences in the assessment of nutrient composition with inconsistent food composition tables.

As an example, a single hour dietary recall may not represent usual food selection Moreover, the measurements of diet at one point cannot reflect long-term intake owing to possible changes in dietary practices over the years. There remain discrepancies regarding the cognitive performance measured and the tasks used, and there is even quite a little confusion on the terms applied for the same test, which makes across-study comparisons difficult.

Besides, some tests of global cognition used to screen cognitive deficits or dementia, such as the MMSE, appear not sensitive enough to detect subtle domains. It could be more powerful to utilize demanding neuropsychological tests covering a wider range of functions.

If conditions permit, the use of functional magnetic resonance imaging can better support findings from cognitive screenings. On the other hand, the durations of intervention range from 4 weeks to 2. In addition, many factors to which cognitive function is sensitive should be taken into account, such as mood, sleep, physical activities, other illnesses, and genetic factors 5 , Finally, RCTs can provide stronger evidence on the causal association of polyphenol intake with cognitive function; nevertheless, the sample sizes are relatively small, with fewer than participants in the majority of studies, and the effect of short-term supplementation in clinical studies may not be comparable with long-term dietary intake Therefore, future investigations with a larger sample of subjects particularly in pre-clinical or MCI stage , longer intervention periods, and longer follow-up after the end of supplement use should determine whether those benefits can be validated and transferred to humans.

In the absence of curative treatment, nutrients from health diet are important modifiable factors for cognitive aging and dementia.

Certainly, discrepancies in study design partly bring about inconsistent findings on the same component. Noteworthy, it is essential to identify the effective dose and duration of supplementation, enhance the bioavailability of substances, and establish standardized preparation, to ensure polyphenol levels sufficient for the protective action.

Furthermore, the possibility of interactions with other bioactives present in foods or that can be administered as supplements e. Even if human polyphenol research on cognitive function is at an early stage and much work needs to be done, the observed associations are promising and call for future investigation.

EB Larson, K Yaffe, KM Langa. New insights into the dementia epidemic. N Engl J Med ; 24 — Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar. R Sahathevan. Chapter 18 — Dementia: An Overview of Risk Factors. C Patterson.

The World Alzheimer Report The state of the art of dementia research: New frontiers. Google Scholar. AFG Cicero, F Fogacci, M Banach. Botanicals and phytochemicals active on cognitive decline: The clinical evidence. Pharmacol Res ;— Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar.

S Rajaram, J Jones, GJ Lee. Plant-Based Dietary Patterns, Plant Foods, and Age-Related Cognitive Decline. Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar. SM Poulose, MG Miller, T Scott, et al. Nutritional Factors Affecting Adult Neurogenesis and Cognitive Function.

Adv Nutr ;8 6 — P Hajieva. The Effect of Polyphenols on Protein Degradation Pathways: Implications for Neuroprotection. G Mazzanti, S Di Giacomo. Curcumin and Resveratrol in the Management of Cognitive Disorders: What is the Clinical Evidence?

RS Turner, RG Thomas, S Craft, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of resveratrol for Alzheimer disease. Neurology ;85 16 — JM Ringman, SA Frautschy, E Teng, et al. Alzheimers Res Ther ;4 5 A Crozier, IB Jaganath, MN Clifford. Dietary phenolics: chemistry, bioavailability and effects on health.

Nat Prod Rep ;26 8 — PC Guest. Reviews on New Drug Targets in Age-Related Disorders. CG Fraga, KD Croft, DO Kennedy, et al. The effects of polyphenols and other bioactives on human health. Food Funct ;10 2 — C Colizzi. Alzheimers Dement N Y ;— Article Google Scholar.

C Spagnuolo, M Napolitano, I Tedesco, et al. Neuroprotective Role of Natural Polyphenols. Curr Top Med Chem ;16 17 — E Nurk, H Refsum, CA Drevon, et al. Intake of flavonoid-rich wine, tea, and chocolate by elderly men and women is associated with better cognitive test performance.

J Nutr ; 1 — C Butchart, J Kyle, G McNeill, et al. Flavonoid intake in relation to cognitive function in later life in the Lothian Birth Cohort Br J Nutr ; 1 — S Kalmijn, EJ Feskens, LJ Launer, et al. Polyunsaturated fatty acids, antioxidants, and cognitive function in very old men.

Am J Epidemiol ; 1 — D Laurin, KH Masaki, DJ Foley, et al. Midlife dietary intake of antioxidants and risk of late-life incident dementia: the Honolulu-Asia Aging Study. Am J Epidemiol ; 10 — Article PubMed Google Scholar. MJ Engelhart, MI Geerlings, A Ruitenberg, et al.

Dietary intake of antioxidants and risk of Alzheimer disease. JAMA ; 24 — EE Devore, F Grodstein, FJ van Rooij, et al. Dietary antioxidants and long-term risk of dementia.

Arch Neurol ;67 7 — D Commenges, V Scotet, S Renaud, et al. Intake of flavonoids and risk of dementia. Eur J Epidemiol ;16 4 — E Shishtar, GT Rogers, JB Blumberg, et al. Long-term dietary flavonoid intake and risk of Alzheimer disease and related dementias in the Framingham Offspring Cohort.

Am J Clin Nutr ; 2 — EE Devore, JH Kang, MM Breteler, et al. Dietary intakes of berries and flavonoids in relation to cognitive decline. Ann Neurol ;72 1 — L Letenneur, C Proust-Lima, A Le Gouge, et al.

Flavonoid intake and cognitive decline over a year period. Am J Epidemiol ; 12 — DR Doerge, DM Sheehan. Goitrogenic and estrogenic activity of soy isoflavones. Environ Health Perspect ; Suppl — FM Sacks, A Lichtenstein, L Van Horn, et al.

Soy protein, isoflavones, and cardiovascular health: an American Heart Association Science Advisory for professionals from the Nutrition Committee. Circulation ; 7 — M Igase, K Igase, Y Tabara, et al.

Cross-sectional study of equol producer status and cognitive impairment in older adults. Geriatr Gerontol Int ;17 11 — E Hogervorst, T Sadjimim, A Yesufu, et al. High tofu intake is associated with worse memory in elderly Indonesian men and women. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord ;26 1 — X Xu, S Xiao, TB Rahardjo, et al.

Tofu intake is associated with poor cognitive performance among community-dwelling elderly in China. J Alzheimers Dis ;43 2 — LR White, H Petrovitch, GW Ross, et al. Brain aging and midlife tofu consumption.

J Am Coll Nutr ;19 2 — PF Cheng, JJ Chen, XY Zhou, et al. Do soy isoflavones improve cognitive function in postmenopausal women? A meta-analysis. Menopause ;22 2 — S Kreijkamp-Kaspers, L Kok, DE Grobbee, et al. Effect of soy protein containing isoflavones on cognitive function, bone mineral density, and plasma lipids in postmenopausal women: a randomized controlled trial.

JAMA ; 1 — LR Fournier, TA Ryan Borchers, LM Robison, et al. The effects of soy milk and isoflavone supplements on cognitive performance in healthy, postmenopausal women. J Nutr Health Aging ;11 2 — CAS PubMed Google Scholar. VW Henderson, JA St John, HN Hodis, et al.

Long-term soy isoflavone supplementation and cognition in women: a randomized, controlled trial. Neurology ;78 23 — S Basaria, A Wisniewski, K Dupree, et al.

Effect of high-dose isoflavones on cognition, quality of life, androgens, and lipoprotein in post-menopausal women. J Endocrinol Invest ;32 2 — SC Ho, AS Chan, YP Ho, et al. Effects of soy isoflavone supplementation on cognitive function in Chinese postmenopausal women: a double-blind, randomized, controlled trial.

Menopause ;14 3 Pt 1 — RF Santos-Galduroz, JC Galduroz, RL Facco, et al. Effects of isoflavone on the learning and memory of women in menopause: a double-blind placebo-controlled study. Braz J Med Biol Res ;43 11 — ML Casini, G Marelli, E Papaleo, et al. Psychological assessment of the effects of treatment with phytoestrogens on postmenopausal women: a randomized, double-blind, crossover, placebo-controlled study.

Fertil Steril ;85 4 — D Kritz-Silverstein, D Von Muhlen, E Barrett-Connor, et al. Isoflavones and cognitive function in older women: the SOy and Postmenopausal Health In Aging SOPHIA Study.

Menopause ;10 3 — SE File, DE Hartley, S Elsabagh, et al. Cognitive improvement after 6 weeks of soy supplements in postmenopausal women is limited to frontal lobe function.

Menopause ;12 2 — R Duffy, H Wiseman, SE File. Improved cognitive function in postmenopausal women after 12 weeks of consumption of a soya extract containing isoflavones. Pharmacol Biochem Behav ;75 3 — AA Thorp, N Sinn, JD Buckley, et al.

Soya isoflavone supplementation enhances spatial working memory in men. Br J Nutr ; 9 — SE File, N Jarrett, E Fluck, et al. Eating soya improves human memory Psychopharmacology Berl ; 4 — Article CAS Google Scholar.

E Hogervorst, F Mursjid, D Priandini, et al. Borobudur revisited: soy consumption may be associated with better recall in younger, but not in older, rural Indonesian elderly. Brain Res ;— CE Gleason, CM Carlsson, JH Barnet, et al. A preliminary study of the safety, feasibility and cognitive efficacy of soy isoflavone supplements in older men and women.

Age Ageing ;38 1 — D Chen, SB Wan, H Yang, et al. EGCG, green tea polyphenols and their synthetic analogs and prodrugs for human cancer prevention and treatment. Adv Clin Chem ;— QP Ma, C Huang, QY Cui, et al.

Meta-Analysis of the Association between Tea Intake and the Risk of Cognitive Disorders. PLoS One ;11 11 :e X Liu, X Du, G Han, et al. Association between tea consumption and risk of cognitive disorders: A dose-response meta-analysis of observational studies. Oncotarget ;8 26 — EL Wightman, CF Haskell, JS Forster, et al.

Epigallocatechin gallate, cerebral blood flow parameters, cognitive performance and mood in healthy humans: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover investigation. Hum Psychopharmacol ;27 2 — K Ide, H Yamada, N Takuma, et al. Green tea consumption affects cognitive dysfunction in the elderly: a pilot study.

Nutrients ;6 10 — Effects of green tea consumption on cognitive dysfunction in an elderly population: a randomized placebo-controlled study.

Nutr J ;15 1 Y Baba, S Inagaki, S Nakagawa, et al. Effect of Daily Intake of Green Tea Catechins on Cognitive Function in Middle-Aged and Older Subjects: A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Study.

AN Sokolov, MA Pavlova, S Klosterhalfen, et al. Chocolate and the brain: neurobiological impact of cocoa flavanols on cognition and behavior. Neurosci Biobehav Rev ;37 10 Pt 2 — GE Crichton, MF Elias, A Alkerwi. Chocolate intake is associated with better cognitive function: The Maine-Syracuse Longitudinal Study.

Appetite ;— RS Calabro, MC De Cola, G Gervasi, et al. The Efficacy of Cocoa Polyphenols in the Treatment of Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Retrospective Study. A Moreira, MJ Diogenes, A de Mendonca, et al. Chocolate Consumption is Associated with a Lower Risk of Cognitive Decline.

J Alzheimers Dis ;53 1 — AB Scholey, SJ French, PJ Morris, et al. Consumption of cocoa flavanols results in acute improvements in mood and cognitive performance during sustained mental effort. J Psychopharmacol ;24 10 — DT Field, CM Williams, LT Butler. Consumption of cocoa flavanols results in an acute improvement in visual and cognitive functions.

Physiol Behav ; 3—4 — AM Brickman, UA Khan, FA Provenzano, et al. Enhancing dentate gyrus function with dietary flavanols improves cognition in older adults. Nat Neurosci ;17 12 — This research has included studies into the mood and cognitive effects of polyphenols within the diet and also on individual classes of polyphenols from sources including tea, cocoa, wine, and soy as well as nondietary botanical sources.

Recent research has revealed some of the biologically plausible systemic and central mechanisms contributing to these effects. These include benefits to cerebral blood flow and patterns of brain activation measured using functional imaging methodology.

Taken together, this body of evidence suggests that polyphenols may be useful additions to lifestyle changes, which may help to offset dementia and cognitive ageing. All rights reserved. Copyright: Copyright Elsevier B. N2 - Polyphenols are known to influence a number of biological systems relevant to brain function.

AB - Polyphenols are known to influence a number of biological systems relevant to brain function. Polyphenols for Brain and Cognitive Health.

Katherine H. Polyphenols are known to influence a fnuction of biological Digestive health diet relevant to brain function. Converging Polyphenols and cognitive function funchion epidemiology and randomized controlled trials suggests that polyphenol Polpyhenols can both Poluphenols against age-related cognitive decline and enhance cognitive function although dose and duration of intake appear critical. This research has included studies into the mood and cognitive effects of polyphenols within the diet and also on individual classes of polyphenols from sources including tea, cocoa, wine, and soy as well as nondietary botanical sources. Recent research has revealed some of the biologically plausible systemic and central mechanisms contributing to these effects. BMC Geriatrics volume 23Article number: Cite this article. Metrics details. Polyphenols Enhances joyful emotions been shown to be effective against many chronic diseases, including neurodegenerative diseases. Polyphenols and cognitive function, the consumption of Pollyphenols, being a cognitiive rich Polyphenol polyphenols, has been Polyphenole with neuroprotective benefits. Polyphsnols, our main objective is to evaluate the effect of including 50 g of raisins in the diet daily for 6 months, on the improvement of cognitive performance, cardiovascular risk factors and markers of inflammation in a population of older adults without cognitive impairment. Design and intervention: This study will be a randomized controlled clinical trial of two parallel groups. Each subject included in the study will be randomly assigned to one of two study groups: control group no supplementintervention group 50 g of raisins daily during 6 months.

die sehr guten Informationen

Es ist die richtigen Informationen