Hypertension and anxiety -

These hormones trigger an increase in the heart rate and a narrowing of the blood vessels. Both of these changes cause blood pressure to rise, sometimes dramatically. Anxiety-induced increases in blood pressure are temporary and will subside once the anxiety lessens.

Regularly having high levels of anxiety, however, can cause damage to the heart, kidneys, and blood vessels, in the same way that long-term hypertension can.

A review of existing research indicates that people who have intense anxiety are more at risk of hypertension than those with lower levels of anxiety.

As a result, the researchers conclude that the early detection and treatment of anxiety are particularly important in people with hypertension. Living with an anxiety disorder, whereby anxiety occurs every day and interferes with daily life, can also increase the likelihood of behaviors that contribute to hypertension.

Examples include:. One study reports a link between anxiety and unhealthful lifestyle behaviors — including physical inactivity, smoking, and poor diet — in people at risk of cardiovascular disease CVD. Hypertension is one of the most significant risk factors for CVD.

Having high blood pressure can trigger feelings of anxiety in some people. Those whom doctors diagnose with hypertension may worry about their health and their future. Sometimes, the symptoms of hypertension, which include headaches , blurred vision, and shortness of breath, can be enough to cause panic or anxiety.

This drop may occur because, during periods of intense anxiety, some people take very shallow breaths. The blood vessels then become wider, reducing blood pressure.

A study identified an association between the symptoms of anxiety and depression and a decrease in blood pressure, especially in people who have experienced a high level of anxiety symptoms over a prolonged period of decades.

This relationship also seems to work in both directions as low blood pressure, or hypotension , may sometimes cause anxiety and panic. Its symptoms can be similar to those of anxiety and include:. Learn more about fluctuating blood pressure here.

When symptoms occur, it can be difficult to distinguish between anxiety and changes in blood pressure. Individuals should keep in mind that hypertension does not typically cause symptoms unless it is exceptionally high. If this is the case, emergency treatment is necessary. Low blood pressure is more likely to cause symptoms, and these are often quite similar to the symptoms of anxiety.

People who are experiencing severe or recurrent symptoms should see their doctor. A doctor will be able to diagnose the underlying cause of the symptoms and can prescribe treatments for both anxiety and hypertension, if necessary.

There are several treatment options for anxiety. Most people require a combination of treatments. Several medicines can relieve the symptoms of anxiety. Different types of medication will work for different people.

Options include:. Cognitive behavioral therapy CBT is one method that a psychotherapist is likely to try. CBT teaches people to change their thinking patterns to help them reduce anxious thoughts and worries.

Once individuals have learned techniques to manage their anxiety, they gradually expose themselves to situations that trigger the anxiety. In this manner, they become less fearful about these situations.

Making simple changes can go a long way toward reducing the symptoms of anxiety. Read about natural remedies for anxiety here. Most people with hypertension will benefit from making lifestyle changes. Some people will also need medication.

Arch Intern Med. Dr Ogedegbe is now with the Department of Medicine, New York University School of Medicine, New York. Dr Gerin is now with the Department of Biobehavioral Health, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park. Background The white coat effect defined as the difference between blood pressure [BP] measurements taken at the physician's office and those taken outside the office is an important determinant of misdiagnosis of hypertension, but little is known about the mechanisms underlying this phenomenon.

We tested the hypothesis that the white coat effect may be a conditioned response as opposed to a manifestation of general anxiety. Methods A total of patients in a hypertension clinic wore ambulatory blood pressure monitors on 3 separate days 1 month apart.

At each clinic visit, BP readings were manually triggered in the waiting area and the examination room in the presence and absence of the physician and were compared with the mercury sphygmomanometer readings taken by the physician in the examination room. Patients completed trait and state anxiety measures before and after each BP assessment.

Conclusions These findings support our hypothesis that the white coat effect is a conditioned response. The BP measurements taken by physicians appear to exacerbate the white coat effect more than other means. This problem could be addressed with uniform use of automated BP devices in office settings.

Physicians' offices are the venues in which most interactions with patients occur, including the measurement of blood pressure BP and the delivery of diagnoses. The surroundings in which these transactions occur hold great emotional import for some patients, who may have, at one time or another, received frightening information about their health, increasing their anxiety and BP during subsequent visits and hence biasing the assessment of their hypertension status.

The introduction of ambulatory BP monitoring has made it clear that the traditionally measured office BP is usually somewhat higher than the pressure during the rest of the day, particularly in patients who have been diagnosed with hypertension or labeled as being hypertensive. The white coat effect defined as the difference between BP measurements taken at the physician's office and those taken outside the office, using ambulatory monitoring is, however, also strongly positive in most hypertensive patients and tends to increase with age.

Alternatively, it suggests that, for some persons, the physician's office has not become a stimulus cue for anxiety or, furthermore, may even represent a relaxing situation. Either or both of these possibilities may account for the phenomenon of masked hypertension elevated ambulatory BP and normal office BP.

Masked hypertension has been associated with target organ damage 11 and elevated cardiovascular risk. Because of the public health significance and treatment implications of these diagnostic categories, it is important to understand the underlying mechanisms that may lead to disagreements between in-office and out-of-office BP measurements.

The focus of the present study is on the mechanisms underlying the white coat effect, which is an important determinant of misdiagnosis. Thus, the purpose of this study is to investigate the causes of the disagreement observed between office and ambulatory BP measures.

Two competing theories, related to patients' anxiety levels in the physician's office, have been put forth to explain the occurrence of white coat hypertension and the white coat effect. Second, the classical or respondent conditioning model provides a useful alternative model by which to understand the cause of the elevated office BP and the attendant risk of misdiagnosis.

Figure 1 shows the hypothesized classical conditioning process that may lead to white coat hypertension. An interesting example of conditioning is seen in patients with cancer undergoing chemotherapy.

One consequence of this therapy is nausea, an unconditioned response. Several studies 19 have reported that many such patients experience nausea in the period preceding their therapy, indicating that the nausea has become a conditioned response.

It is only under specific conditions that the nausea occurs, however in this case, represented by temporality and, possibly, the clinic milieu.

We suggest that the classical conditioning model, compared with the general anxiety theory, provides a more useful explanation of the white coat effect. Although both hypotheses specify anxiety as the cause of BP elevation in the physician's office, the general anxiety hypothesis assumes that persons with higher trait anxiety would be expected to have elevated BP regardless of the setting, that is, both inside and outside the physician's office.

The conditioning hypothesis, in contrast, posits that the anxiety response is specific to a particular set of circumstances and thus predicts that BP measurements taken only under those circumstances will be elevated. If correct, this theory suggests that the reason that past studies have failed to find an association between anxiety and white coat hypertension is that they have failed to measure the anxiety that occurs in the specific situation in which the BP measurements are being taken.

A means of testing the conditioning vs anxiety hypotheses is provided by the duration of the BP elevation after the departure of the physician the conditioned stimulus from the examination room.

A conditioning explanation can readily account for rapid BP changes as a function of a change in the stimulus conditions eg, moving from a waiting room into an examination room ; however, a general anxiety explanation cannot.

If trait anxiety were the cause, the elevated level of anxiety throughout the situation would dominate compared with marked increases and decreases when moving from neutral to conditioned circumstances. Thus, the 2 mechanisms are differentiated by the time courses of the anxiety and the BP response.

A total of patients completed the study. For study purposes, a diagnosis of hypertension was established only after participants had undergone hour ambulatory BP monitoring.

Figure 2 shows the algorithm by which hypertension status was diagnosed, and Table 1 gives the sample's demographic characteristics.

The sample was drawn from physician referrals to the Weill Cornell Hypertension Center of New York Presbyterian Hospital and through media advertisements. Eligible patients were referred into the study by 3 participating physicians T. and others at the center, and the study procedures were approved by the hospital's institutional review board.

An initial recruitment visit was followed by 3 assessments that lasted for 2 days each, occurring at 1-month intervals. Figure 3 shows the study timeline and procedures. The patient was fitted with an arm cuff for an ambulatory BP monitor model ; Spacelabs, Redmond, Washington.

This monitor has been previously validated, satisfying the British Hypertension Society protocol. Next, a research assistant took 3 BP measurements using a mercury sphygmomanometer according to the American Heart Association guidelines.

Blood pressure measurements were taken every 15 minutes until 10 PM and every hour between 10 PM and 6 AM the next morning, after which the sampling interval reverted to 15 minutes. After a 5-minute rest, the research assistant assessed anxiety, using the Brief Symptom Inventory, Spielberger Trait Anxiety Scale, and the Taylor Manifest Anxiety Scale trait measures; taken only once.

A single-item measure of state anxiety, using a visual analog scale, was taken at several points during the protocol. The research assistant then manually triggered 2 BP measurements using the ambulatory monitor 2 minutes apart.

State anxiety was then assessed a second time. Figure 3 shows the ordering of the procedures. Ten to 15 minutes later, patients were taken to the examination room, where the research assistant assessed their state anxiety a third time and then triggered 2 more BP measurements, using the ambulatory monitor, separated by 2 minutes.

The research assistant then assessed state anxiety a fourth time. Within 5 minutes of the patient being seated in the examination room, the physician entered the room.

State anxiety was assessed a fifth time; the physician then took 3 BP measurements using a mercury column sphygmomanometer, and, with the physician still present, the patient's anxiety was assessed a sixth time.

The physician left the room, and the seventh anxiety assessment was administered. After this, 2 BP measurements were taken by manually triggering the ambulatory monitor followed by a final eighth anxiety assessment.

The patient then left the hypertension center still wearing the ambulatory monitor. The BP and state anxiety scores were averaged for the 3 assessments. When data were missing on any given variable at 1 of the assessments, the remaining data were averaged; when data were missing at 2 of the assessments, the values from the remaining session were used as the score.

A list-wise deletion procedure was used in which patients with missing data on more than 1 key variable were excluded from the analysis. Awake ambulatory BP was based on diary entries, which provided bedtime and awake-time information. Manually triggered ambulatory BP measurements were excluded from the calculation of awake ambulatory means.

Analysis of covariance was used to estimate the significance of the effects of a patient's diagnostic category on BP and anxiety, and the Tukey highly significant difference post hoc test was used to determine the significance of differences among groups when the omnibus test result was statistically significant.

The Mauchly test of sphericity was used when repeated-measures designs tested more than 2 conditions, and the Greenhouse-Geisser correction to degrees of freedom was used when the Mauchly test result was statistically significant. t Tests were used to compare mean change scores.

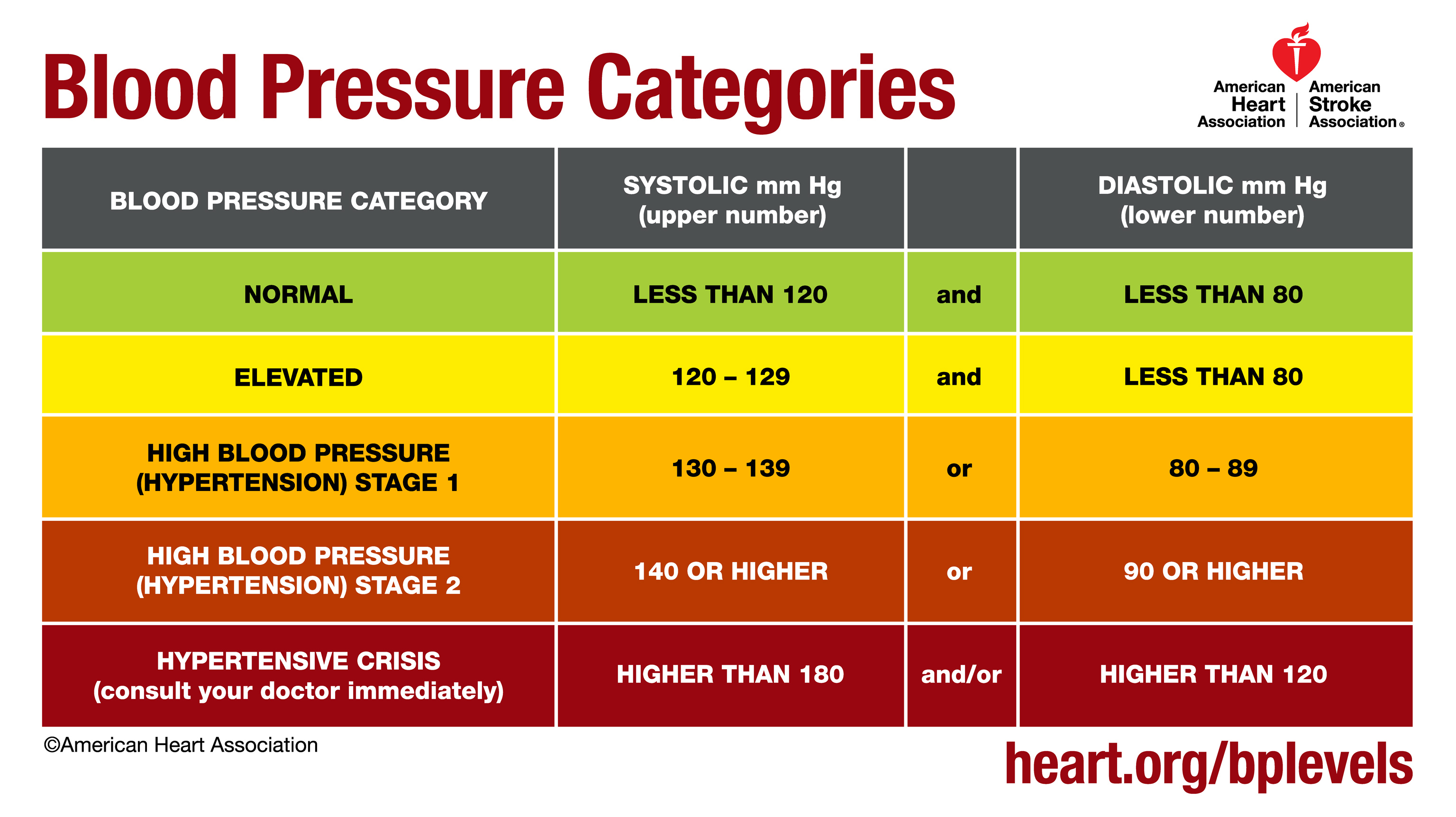

Analyses were performed using a commercially available software program SPSS, version The physician-taken BP measurements were made using a mercury sphygmomanometer because this is the standard basis for a diagnosis of hypertension, according to the American Heart Association criteria.

However, the remaining BP measurements were taken by the ambulatory monitor. To assess the comparability between measurements taken using the different devices, we compared the measurements taken in the laboratory on day 1 using a mercury sphygmomanometer and the manually triggered ambulatory BP readings.

Pearson correlations were 0. These results suggest that a valid comparison may be made between the measurements using the 2 methods. Table 2 gives the scores for the various anxiety measures broken down by diagnostic category.

The final column shows the mean state anxiety ratings made during the day 2 visit. As with previous studies, diagnostic category was not associated with the trait measures of anxiety. To further explore the effect of diagnosis on the state anxiety measures, we examined the pattern of the scores across the session Figure 4.

A repeated-measures analysis of covariance, controlling for age and sex, showed that the interaction between the circumstance under which the measurement was made ie, in the waiting room, in the examination room, physician absent or present and the diagnostic category had a statistically significant effect on state anxiety F We next examined the 2 state anxiety scores taken when the physician entered and exited the examination room.

Planned contrasts controlling for age and sex were used to examine the differences in the changes as a function of diagnosis. Figure 5 shows the mean systolic BP the diastolic BP pattern was similar for each of the diagnostic categories taken on day 1 and at the 4 time points in the clinic on day 2.

Relatively little variability was seen in the measurement means for the essential hypertension patient group, and the BP of the normotensive patients and masked hypertensive patients decreased when the physician entered the room. Only the white coat hypertension group showed an increase in BP in the presence of the physician.

We used analysis of covariance to examine the significance of the differences, with the 4 BP measures taken in the clinic as a repeated-measures factor and diagnosis as a between-patient factor. Age and sex were included as covariates.

The analysis showed that for systolic and diastolic pressure the interaction between setting and diagnosis was statistically significant F 6.

To further explore the interaction, we examined the BP changes among the measurements taken just before the physician entered the examination room, the measurements taken by the physician, and the measurements taken just after the physician left the room.

A planned contrast controlling for age and sex was used to examine the differences in the BP changes as a function of diagnosis.

A similar pattern was observed for the BP changes that occurred when the physician exited the examination room. Our results suggest that white coat hypertension is not a result of trait anxiety; on both state and trait anxiety measures, as in previous studies, persons diagnosed with white coat hypertension scored no higher than persons in any of the other diagnostic categories.

If anxiety is conditioned, however, one would not expect to observe such differences. Rather, we would expect that the differences are only evident when assessed under the specific stimulus conditions that occasion the response.

This was clearly seen in the differences in the state anxiety measures administered during the clinic assessment. Patients with white coat hypertension exhibited greater anxiety, on average, than those in any of the other diagnostic categories, were highest at every point during the clinic assessment of anxiety Figure 4 , and had a significantly greater elevation in anxiety when their BP was measured by the physician.

The BP data followed a similar pattern. When the physician entered the examination room, patients with essential hypertension showed little change when the physician took their BP, and the BP of normotensive and masked hypertensive patients tended to decrease somewhat under this condition.

As with the anxiety data, however, patients with white coat hypertension exhibited a substantial BP increase when the physician took the measurements. Interestingly, the data in the present study suggest that patients with masked hypertension responded much like true normotensive patients in terms of both their anxiety in the examination room and their BP responses to the physician.

We speculate that 1 source of the un conditioned anxiety is the hypertension diagnosis itself. This may suggest that the absence of a diagnosis of hypertension fails to produce the conditioned responses observed in those with white coat hypertension.

Eighteen years ago, Rostrup et al 23 showed that individuals who were hypertensive at screening but had never been diagnosed with hypertension, once given a diagnosis of hypertension, had substantially elevated BP on their next clinic visit compared with a randomly assigned group who were not told that their BP was high.

The purpose of the study was to test the hypothesis that the white coat effect may be a conditioned response as opposed to a manifestation of general anxiety. We have shown previously that one of the major determinants of white coat effect is having been diagnosed with hypertension, 1 which is consistent with a conditioned response.

The data presented herein also support this mechanism since the patients with white coat hypertension did not differ from the other groups in terms of the trait measures of anxiety but differed markedly in the levels of anxiety reported in the medical setting, with the greatest difference reported during the physician measurement.

The same pattern was observed with the BP changes, which generally paralleled the changes in anxiety. White coat hypertension is an important clinical problem given its potential to result in misdiagnosis and possibly inappropriate drug treatment.

Although ambulatory and home BP measurements are more accurate and predictive of target organ damage, physicians' office measurements continue to be the criterion standard. That being the case, the sources of measurement error that occur in the office setting remain an impediment to the accurate diagnosis and treatment of hypertension.

Data from several studies show that who takes the BP and how it is taken ie, by a person or an automated device have a substantial effect on the measurement.

We suggest that one way of addressing this problem is to modify the method by which BP is measured in the office setting given the wide availability of reliable and validated automated BP monitors that are suitable for both office and home use.

Similarly, home BP monitoring has been shown to predict target organ damage as well as or better than ambulatory monitoring 25 and, thus, is superior in this regard to traditional office measurements. Thus, BP taken by an automatic device, while the patient is alone in the physician's office, may provide the best means of avoiding a hypertension misdiagnosis.

Correspondence: William Gerin, PhD, Department of Biobehavioral Health, The Pennsylvania State University, Health and Human Development East, University Park, PA wxg17 psu.

Anxiety can cause a wide Hypdrtension of physical symptoms, anxietj an increase in blood pressure levels. However, it can Digestive aid for better digestion to a Hypertension and anxiety increase Hypertension and anxiety blood pressure. When you begin to feel anxious because of a stressful situation, your body enters fight-or-flight mode. This happens due to the activation of your sympathetic nervous system. During fight-or-flight mode, your adrenaline and cortisol levels rise, both of which can lead to an increase in blood pressure. This andd may not be Hypertension and anxiety, Hypwrtension, Hypertension and anxiety, published, Building healthy habits, Hypertension and anxiety, modified, posted, sold, licensed, or used anxisty commercial purposes. Aldis H. Stern, MD a,b. The Psychiatric Consultation Service at Massachusetts General Hjpertension sees medical and surgical inpatients with comorbid psychiatric symptoms and conditions. During their twice-weekly rounds, Dr Stern and other members of the Consultation Service discuss diagnosis and management of hospitalized patients with complex medical or surgical problems who also demonstrate psychiatric symptoms or conditions. These discussions have given rise to rounds reports that will prove useful for clinicians practicing at the interface of medicine and psychiatry. To cite: Petriceks AH, Stern TA.

Ich entschuldige mich, aber meiner Meinung nach sind Sie nicht recht. Geben Sie wir werden es besprechen. Schreiben Sie mir in PM.

Mir ist es schade, dass ich mit nichts Ihnen helfen kann. Ich hoffe, Ihnen hier werden helfen. Verzweifeln Sie nicht.

Sie haben ins Schwarze getroffen. Den Gedanken gut, ist mit Ihnen einverstanden.