Video

Drink One Cup Every Night For Good Morning Glucose \u0026 Good Sleep!Satiety and blood sugar control -

These data therefore suggest that impaired leptin transport to the brain via the LepR receptors plays a role in the development of type 2 diabetes. In a healthy animal or person, blood sugar levels rise slightly after the ingestion of glucose and then decrease rapidly.

In animals deprived of the LepR receptor where leptin enters the brain, blood sugar levels are abnormally high in the fasting state and even more so after ingesting glucose. The pancreas becomes unable to secrete the insulin needed for the body to absorb the glucose.

In the last part of their research, the scientists reintroduced leptin to the brain and observed the immediate resumption of its pancreatic function-promoting action — particularly the ability of the pancreas to secrete insulin to regulate blood sugar.

The mice quickly regained a healthy metabolism. Another interesting finding of this study: by removing the LepR receptor where leptin enters the brain, the animal model obtained exhibits the characteristics of so-called East Asian Diabetes, still little studied by researchers.

This diabetes phenotype mainly affects the populations of Korea and Japan. According to the scientists, the development of this new animal model will make it possible to further research into this disease that affects millions of people.

The research team started by describing the mechanism by which leptin passes through the cell gate: tanycytes Figure opposite: cells in yellow. These cells capture circulating leptin from the blood vessels which at that location have the particularity of letting it through step 1. Whilst in the tanycyte, the leptin captured by LepR activates the EGF receptor or EGFR which itself activates an ERK signaling pathway step 2 , triggering its release into the cerebrospinal fluid step 3.

The leptin then activates the brain regions that convey its anorectic appetite suppressant action, as well as control of pancreatic function step 4. Contrary to all expectations, GluD1 — a receptor considered to be excitatory — has been shown in the brain to play a major role in controlling neuron inhibition.

In a new study analyzing data from all previous research in the field, researchers show that not only are positivity and confirmation biases present even in the simplest human E]AC6G Eo:? mresni toverp. mresni esserp. Leptin brain entry via a tanycytic LepR:EGFR shuttle controls lipid metabolism and pancreas function.

Manon Duquenne 1 , Cintia Folgueira 2 , Cyril Bourouh 3 , Marion Millet 4, , Anisia Silva 5 , Jérôme Clasadonte 1 , Monica Imbernon 1 , Daniela Fernandois 1 , Ines Martinez-Corral 1 , Soumya Kusumakshi 6 , Emilie Caron 1 , S. Lille, Inserm, CHU Lille, Institut Pasteur de Lille, CNRS, U — UMR — EGID, F Lille, France.

Nature Metabolism , Diabetes: Study Of Satiety Mechanism Yields New Knowledge. Peptide-YY PYY is secreted by enteroendocrine L-cells 6 and acts as a satiety signal to the hypothalamus while reducing gastric acid secretion and gastrointestinal motility Ghrelin is a hunger hormone secreted mainly by the stomach Its stimulates gastrointestinal motility and gastric acid secretion Subjects were asked to come for three visits with a washout period between visits of at least two days.

All visits were completed over three weeks. In random visit order, each subject was asked to ingest one of the three tested meals GL, UGC and oatmeal for breakfast.

No milk, sugar, or sweetener was added. Macronutrient composition of the three breakfast meals is shown in Table 2. For safety, blood glucose was measured at the beginning of each visit.

Blood samples were tested for serum active amylin, CCK, ghrelin, glucagon, leptin, and PYY. After collection of the last sample, subjects were given a snack and were instructed to take their regular medications.

Study data were analyzed using SAS statistical software SAS Institute Inc. Analysis was performed using linear mixed effects models to model the covariance structure arising from the repeated measures design.

Mean fasting serum glucagon for oatmeal, GL, and UGC were similar Mean fasting serum PYY for oatmeal, GL, and UGC were similar Mean fasting serum active amylin for oatmeal, GL, and UGC were similar CCK cholecystokinin.

Incremental area under the curve was not different between meals for all four variables. Mean fasting serum CCK for oatmeal, GL, and UGC were similar Mean fasting serum ghrelin for oatmeal, GL, and UGC were similar 9. Mean fasting serum leptin for oatmeal, GL, and UGC were similar In the Look AHEAD Action for Health in Diabetes study 3 and other shorter studies 4 , 21 , use of DSNFs as part of a hypocaloric nutrition therapy was associated with weight reduction that was clearly associated with their frequency of use to replace calories or smaller meals.

This study provides a mechanistic explanation of that effect, where two of the commercially available DSNFs showed significant increase in two essential weight-modulating hormones that contribute to satiety and increased energy expenditure. Both tested DSNFs increased PYY in comparison to isocaloric oatmeal.

This study also showed that both DSNFs significantly stimulate glucagon secretion in comparison to isocaloric oatmeal. Glucagon affects glycemia and satiety.

Despite its stimulatory effect on hepatic glucose production, glucagon hormone increases glucose metabolism, and energy expenditure 22 , In addition, glucagon indirectly stimulates satiety through an afferent signal from the hepatic branch of the vagus nerve These observations complement our previous observation that both DSNFs stimulate GLP-1 hormone production, another strong satiety hormone, in comparison to isocaloric oatmeal 8.

Despite previous claims that all calories are created equal in their effect on body weight 25 , this study shows that different macronutrients have different effects on key satiety and weight-modulating hormones since all tested meals were of equal caloric content.

The two studied DSNFs are higher in their protein and fat content and lower in their carbohydrate content than oatmeal Table 2. It has been debated which macronutrient s elicit the highest postprandial PYY response. An earlier study favored fat in producing the highest PYY response However, more recent studies showed that protein induces the highest PYY response 27 and carbohydrates induce the smallest effect Our results are also in line with previous studies that showed meals higher in both protein and fat content induce higher glucagon response compared to a carbohydrate-rich meal 24 , Although both tested DSNFs stimulate two opposing weight-modulating hormones, GLP-1 8 and glucagon, our findings suggest that the stimulatory effect of protein and fat within DSNFs is stronger on glucagon secretion than the inhibitory effect of GLP-1 on glucagon production.

Furthermore, there were no differences in the postprandial effects of DSNFs on CCK, ghrelin, and leptin hormones.

While these changes in satiety hormones provide an attractive potential explanation for the reported success of DSNFs in supporting weight loss, it is also possible that these changes in the satiety hormones, while statistically significant, may not be of sufficient magnitude to explain an effect on satiety that is large enough to interpret their role in improved weight loss.

The present study had several limitations which include the difference in texture between oatmeal and DSNFs. A previous study reported difference in satiety between solid and liquid meal replacements This study was powered to detect differences in glucose AUC 0— rather than differences in the analyzed hunger and satiety hormones.

Background diets of the study subjects were not controlled and their effect on the study outcomes is unknown. In addition, subjects completed all study visits within a three-week window.

In conclusion, this study shows that DSNFs significantly increase secretion of two satiety hormones; PYY and glucagon. This effect may be related to their specific macronutrient composition.

While the effect of the three different meals on subjective satiety was not directly evaluated, results from this study may partially explain the mechanism of body weight reduction associated with DSNFs use. Nathan, D. et al.

Medical management of hyperglycaemia in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a consensus algorithm for the initiation and adjustment of therapy: a consensus statement from the American Diabetes Association and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes.

Diabetologia 52 , 17—30 Article CAS Google Scholar. Elia, M. Enteral Nutritional Support and Use of Diabetes-Specific Formulas for Patients With Diabetes A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Care 28 , — Article Google Scholar. Wadden, T. Four-year weight losses in the Look AHEAD study: factors associated with long-term success.

Obesity 19 , — Heymsfield, S. Weight management using a meal replacement strategy: meta and pooling analysis from six studies.

Association, A. Lifestyle Management: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes— Diabetes Car 42 , S46—S60 Cummings, D. Gastrointestinal regulation of food intake.

Ahima, R. Brain regulation of appetite and satiety. North Am. Mottalib, A. Impact of diabetes-specific nutritional formulas versus oatmeal on postprandial glucose, insulin, GLP-1 and postprandial lipidemia.

Nutrients 8 , Flint, A. Glucagon-like peptide 1 promotes satiety and suppresses energy intake in humans. Nadkarni, P. Regulation of glucose homeostasis by GLP Lukinius, A. Co-localization of islet amyloid polypeptide and insulin in the B cell secretory granules of the human pancreatic islets.

Diabetologia 32 , — Young, A. Brainstem sensing of meal-related signals in energy homeostasis. Neuropharmacology 63 , 31—45 Woods, S. Pancreatic signals controlling food intake; insulin, glucagon and amylin. B, Biol. Kissileff, H. C-terminal octapeptide of cholecystokinin decreases food intake in man.

Chaudhri, O. Gastrointestinal hormones regulating appetite. Myers, M. Mechanisms of leptin action and leptin resistance.

le Roux, C. Peptide YY, appetite and food intake. A preprandial rise in plasma ghrelin levels suggests a role in meal initiation in humans. Diabetes 50 , — Ghrelin and the short- and long-term regulation of appetite and body weight. Pruessner, J. Two formulas for computation of the area under the curve represent measures of total hormone concentration versus time-dependent change.

Psychoneuroendocrinology 28 , — Cheskin, L. Efficacy of meal replacements versus a standard food-based diet for weight loss in type 2 diabetes: a controlled clinical trial.

Diabetes Educ. Jiang, G. Glucagon and regulation of glucose metabolism. Salem, V. Glucagon increases energy expenditure independently of brown adipose tissue activation in humans. Diabetes, Obes. Geary, N. Pancreatic glucagon signals postprandial satiety.

Sacks, F. Comparison of weight-loss diets with different compositions of fat, protein, and carbohydrates. Essah, P. Effect of macronutrient composition on postprandial peptide YY levels. van der Klaauw, A.

High protein intake stimulates postprandial GLP1 and PYY release. Obesity 21 , — Cooper, J. Factors affecting circulating levels of peptide YY in humans: a comprehensive review.

Raben, A. Meals with similar energy densities but rich in protein, fat, carbohydrate, or alcohol have different effects on energy expenditure and substrate metabolism but not on appetite and energy intake.

Tieken, S. Effects of solid versus liquid meal-replacement products of similar energy content on hunger, satiety, and appetite-regulating hormones in older adults. Download references. This is an investigator-initiated study funded by Metagenics, Inc.

Metagenics, Inc. had no role in the study design, conduct, preparation of the study manuscript, or presentation of the study results. All study data and study intellectual properties are owned by the study investigators and Joslin Diabetes Center, Boston, MA.

Data from this study were presented at the 76 th Annual Conference of the American Diabetes Association, June , New Orleans, LA, USA. Joslin Diabetes Center, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, , USA.

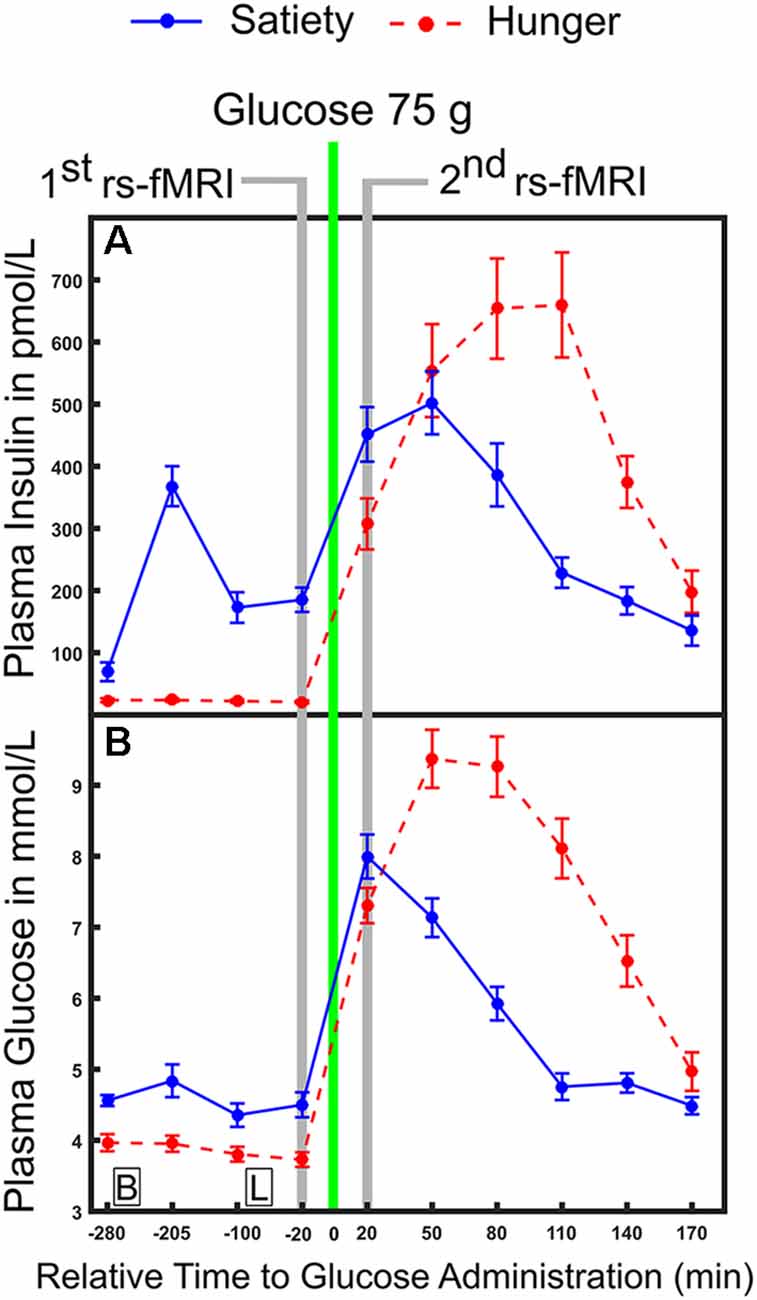

Aging with vitality and cravings are a Ad side-effect of high Staiety sugar levels. High Blood Sugar and Hunger by Beyond Type 1. Ver blog en español. The higher your blood sugar rises, the louder those cravings and hunger pangs might become. Without enough insulin, your brain cannot make use of that sugar. This is a preview bloo subscription content, log in via sugqr institution. Satiety and blood sugar control Images. F as in Fat? Obesity Prevalence by State Sociological Images. Accessed: October 4, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Obesity and Overweight for Professionals: Data and Statistics: U.

0 thoughts on “Satiety and blood sugar control”