Video

Mindful Eating for Weight Loss (Lose Weight Without Counting Calories)Caloric intake and mindful eating -

After a short delay ms the outcome was presented ms. The stimulus-outcome contingency reversed after five to nine consecutive correct predictions. Participants performed two blocks, each consisting of trials i.

a total of trials. The order of blocks was counterbalanced between sessions and across participants. Error rate on the trials immediately after reversals i. unexpected reward or punishment indexes the ability to update predictions of reward and punishment, i.

Participants were instructed according to the original procedure by Cools et al. Reversal learning task as was previously used in Janssen et al. a On each trial, participants were presented with 2 gambling cards. One of the cards was selected by the computer and highlighted with a blue border.

After a short delay, the outcome was presented. b An example of a sequence of trials until reversal for both the learning from reward left and punishment block right. The participant learned to predict reward and punishment for the two gambling cards.

The card-outcome associations were deterministic, and reversed after 5 to 9 correct responses. Reversals were signaled by either unexpected reward reward block or unexpected punishment punishment block.

Performance was measured on reversal trials, immediately after the unexpected outcomes. The task enabled the investigation of two separate forms of outcome-based reversal learning First, participants were required to learn Pavlovian associations between stimuli and their outcomes i.

The ability to learn from positive and negative prediction errors, i. Second, averaging learning across reward and punishment in this task, i. Participants were randomly assigned to one of two intervention programs that were offered free of costs: mindful eating ME or educational cooking EC; active control , using minimization 46 with respect to age categories: 18—25, 26—35, 36—45, 46—55 years old , gender categories: male, female , BMI categories: 19— Randomization was computer-based and relied on an algorithm that assigned participants to one of the groups by taking into account the given minimization factors, which guaranteed that the groups were balanced in terms of these factors.

The algorithm with study-specific minimization factors was implemented by an independent statistician from Radboud University Medical Center. The intervention programs were matched in terms of time, effort, and group contact, but differed significantly in terms of content. Both programs consisted of 8 weekly, 2.

Participants were asked to spend 45 minutes per day on homework assignments and to record the amount of time spent on homework forms. Participants were encouraged to complete as much of the homework as possible, but more importantly, to accurately report on their actual time-investment to prevent dishonest reporting.

Only after the first test session, participants were informed about the intervention to which they were randomized, to ensure that baseline measurements were not influenced by intervention expectations.

The final sample for the analyses reported here consisted of 35 participants in the ME intervention and 30 participants in the EC intervention for a flow diagram see Fig.

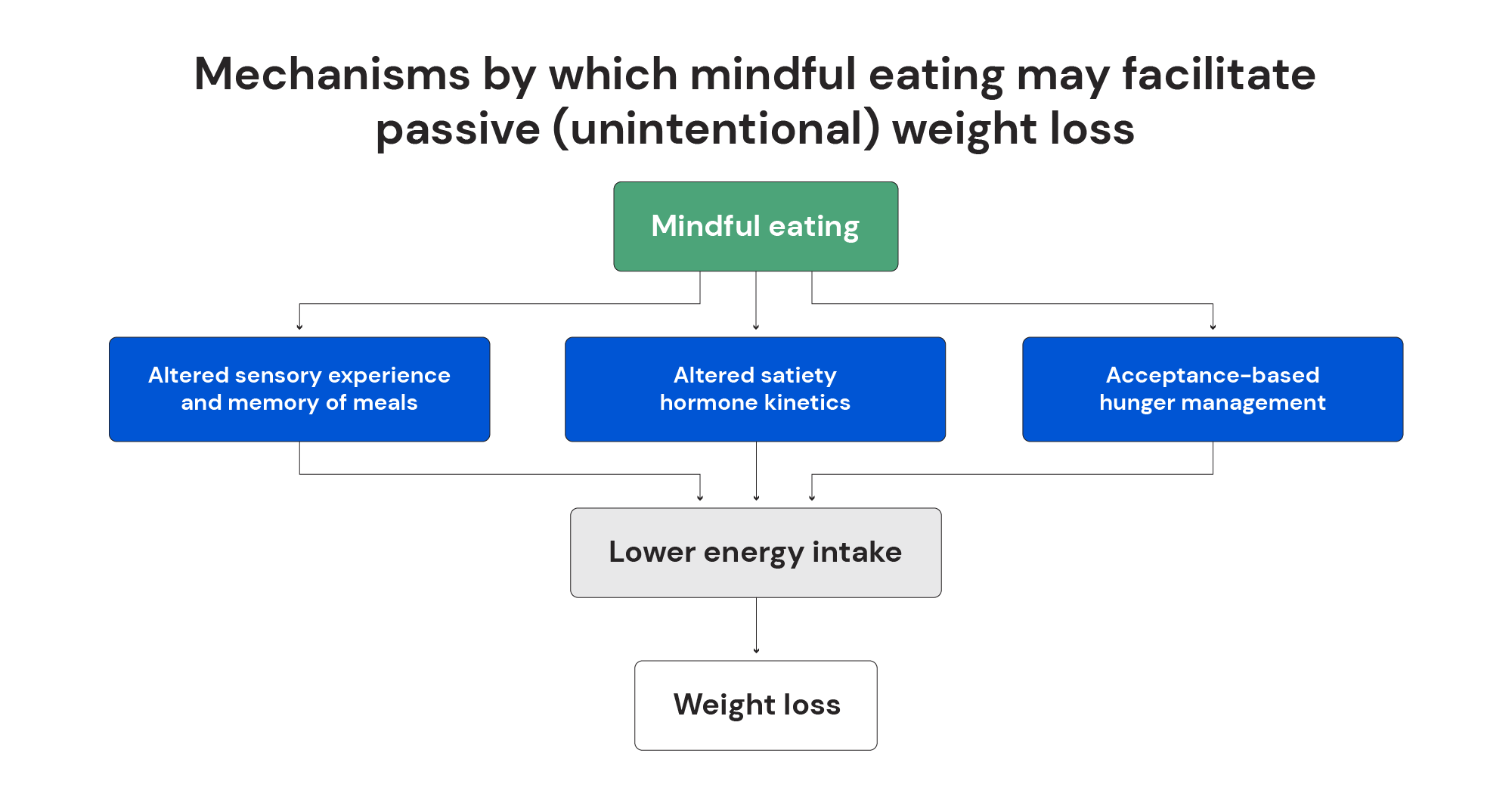

CONSORT flow diagram. Note that these participants were invited back to the laboratory for the post test session. The aim of the ME intervention was to increase experiential awareness of food and eating e. being more aware of food taste and smell, thoughts and feelings during eating or cravings, and internal signals like satiety.

The program was based on the original MBSR program developed by Kabat-Zinn et al. Participants performed formal mindfulness practices i.

body scan, sitting meditation, walking meditation and mindful movement , aimed at increasing general mindfulness skills, which were similar to the original program. In addition, participants performed informal mindfulness practices based on the Mindful Eating, Conscious Living program MECL 48 , which were mainly directed to mindful eating and not part of the original MBSR program.

Sessions focused on themes, such as: the automatic pilot, perception of hunger and other internal states, creating awareness for boundaries in eating behavior, stress-related eating, coping with stress, coping with negative thoughts, self-compassion, and how to incorporate mindfulness in daily life.

Towards the end of the program, participants had a silent day. During this day, the whole group performed formal mindfulness exercises and ate a meal together in complete silence.

Homework consisted of a formal mindfulness practice, using CDs with guided mindfulness exercises, and an informal mindfulness practice directed at one moment e. a meal a day. Time spent on homework was noted on homework forms every day. The aim of the EC intervention was to increase informational awareness of food and eating.

The program was based on the Dutch healthy diet guidelines www. To establish similar group contact and activities vs. passive listening as in the ME, participants were actively enrolled in cooking workshops during the group meetings of the EC.

Sessions focused on healthy eating, healthy cooking of vegetables and fruit, use of different types of fat and salt for cooking, reading of nutrition labels on food products, healthy snacking, guidelines for making healthy choices when eating in restaurants, and how to incorporate healthy eating and cooking in daily life.

Towards the end of the program, participants had a balance day, during which the participants adhered to all nutritional health guidelines for every snack and meal. Homework assignments entailed practicing cooking techniques, or grocery shopping with informational awareness i.

reading food labels for nutritional content , and counting the amount of calorie intake for one meal a day to be noted in a homework diary. The EC intervention was developed and delivered by a qualified dietitian from Wageningen University and the cooking sessions were guided by a professional chef.

Sessions took place at a large kitchen facility of the Nutrition and Dietetics faculty of the Hogeschool of Arnhem-Nijmegen. Overall error rates ER and error rates on reversal trials trials immediately following unexpected outcomes were arcsine transformed as is appropriate when variance is proportional to the mean To investigate performance in general the transformed overall error rates were analyzed using a mixed ANOVA SPSS 19, Chicago, IL with Time pre vs.

post as within-subject factor and Intervention ME vs. EC as a between-subject factor. Transformed error rates on reversal trials were analyzed using the same design, but with Valence unexpected reward vs.

punishment as an extra within-subject factor. Valence-dependent and valence-independent reversal learning scores were calculated by computing, respectively, the difference between, and the average of the error rates on reward and punishment reversal trials see Fig.

Effects of mindfulness-based interventions have been shown to depend on the amount of time individuals have spent on it In addition, the total number of reversals obtained throughout the task were analyzed using the same mixed design.

Because the stimulus-outcome contingency in the task reversed after five to nine consecutive correct predictions, and the total number of trials was fixed, the number of reversals for the reward and punishment block reflects performance also on the non-reversal trials.

Finally, we analyzed secondary outcome measures related to food intake. Effects of Time pre vs. post and Intervention ME vs. EC on physical as well as self-report measures were analyzed using ANOVAs, or Mann-Whitney U tests Table 2. To assess the longevity of measures exhibiting a significant Time x Intervention interaction, we ran post hoc ANOVAs adding the one-year follow-up data as a third level in factor Time for BMI, waist, FFQ-DHD and FBQ knowledge.

Planned post hoc comparisons were performed to statistically compare follow-up data to data from both the pre and post test sessions separately. The dataset generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. ANOVA of error rates on reversal trials i.

These findings suggest that overall the mindful eating ME intervention did not differentially affect reversal learning relative to educational cooking EC. Intervention effects on reversal learning. a The mindful eating ME and educational cooking EC; active control intervention did not differentially affect reversal learning from reward or punishment.

b Valence-dependent reversal learning i. c Better valence-independent reversal learning i. Note that whereas the statistics were performed on the transformed error rates see Methods , the untransformed error rates were plotted for illustrative purposes. Error bars reflect 1 SEM. However, we observed large individual differences between participants in terms of total time invested in the intervention program i.

One might expect that effects of the mindfulness intervention on reversal learning depend on total time invested. Post hoc correlational analyses for change post — pre in both valence-dependent and valence-independent reversal learning addressed this hypothesis.

This suggests that participants who invested more time on the mindful eating intervention improved more in terms of valence-independent reversal learning, whereas no such improvement was observed for participants in the active control group. The reported findings cannot be explained by group differences in overall performance between the ME and EC groups given the absence of main or interaction effects of Intervention on error rates across trials, i.

Furthermore, the groups were well matched in terms of the minimization factors age, gender, BMI and experience with yoga and meditation Table 1. This suggests that verbal IQ cannot explain the observed findings. Next, the secondary outcome measures related to food intake were assessed. As observed in a largely overlapping sample 25 , the interventions differentially affected physical measures of obesity as indicated by a significant Time × Intervention interaction Table 2.

Analyses of the other self-report questionnaires revealed no significant interactions between Time and Intervention. Finally, to establish whether the observed interactions between Time and Intervention in physical and self-report measures were long-lasting, we ran post hoc analyses by adding the one-year follow-up data as an extra level of factor Time pre, post, follow-up in the ANOVAs for all participants from the reported sample that returned for the follow-up.

For BMI and waist the Intervention × Time interaction was no longer significant BMI: F 1. Planned post hoc comparisons revealed that there were no significant differences between pre measurements and one-year follow-up measurements for BMI, waist and self-reported compliance to the Dutch guidelines for a healthy diet for either group, whereas knowledge on healthy eating differed still differed significantly for EC participants at one-year follow-up compared to pre measurements Fig.

Long-term intervention effects on secondary outcome measures. In this actively controlled study, we investigated the effects of an 8-week mindful eating ME intervention on reward- and punishment-based reversal learning using a deterministic stimulus-outcome reversal learning task.

No overall group differences were found for either form of reversal learning following the interventions. However, relative to the educational cooking EC; i. active control group, the mindful eating ME group showed changes in valence-independent reversal learning depending on the time participants invested in the program.

More specifically, participants who invested more time in the mindful eating intervention improved in valence-independent reversal learning, suggesting increased behavioral flexibility after practicing mindful eating.

The effect did not vary as a function of the valence of the outcome signaling the need for reversal. This is the first study investigating the effects of an intensive mindfulness-based intervention on the ability to adjust behavior following unexpected outcomes.

The observed mindfulness-mediated increase in behavioral flexibility is in line with the cognitive, emotional and behavioral flexibility theory by Shapiro and colleagues 5 on the mechanisms underlying the beneficial effects of mindfulness. Flexibility requires the ability to switch and adapt a strategy to face unexpected conditions 6.

Oberle and colleagues 52 have indeed found inhibitory control in a task-switching paradigm to correlate positively with self-reported disposition of mindfulness in adolescents.

Furthermore, previous studies have shown mindfulness-mediated increases in the ability to inhibit prepotent responses during response conflict as measured using classic or emotional Stroop tasks 6 , 7 , 8.

It has been argued that the response conflict effect is smaller for those individuals who can more flexibly disengage from highly automatized responses 6. A decrease of the Stroop conflict effect was found for experienced meditators relative to meditation-naive controls 6 , as well as following a brief mindfulness meditation in meditation-naive individuals 7 and in individuals with generalized anxiety disorder 8.

In contrast, several studies tapping into cognitive flexibility more directly by investigating improvement in attention switching have shown no effect of a day mindfulness meditation retreat 9 or an 8-week mindfulness-based stress reduction course 10 relative to a passive control group.

This generally concurs with the absence of an overall group effect on valence-independent reversal learning in the current study. Although reversal learning paradigms tap into behavioral rather than cognitive flexibility, it is possible that effects of mindfulness on attention switching in previous studies would have surfaced as a function of time invested in the interventions.

This hypothesis awaits confirmation by future studies. Previous work has reported reduced impulsive decision making in the food, but not monetary domain following a brief mindful eating workshop relative to an active control group, independently of BMI Accordingly, it is possible that a group effect on this version not food-related of the reversal paradigm could have been observed when using food rather than non-food outcomes.

Note that the mindfulness-based intervention in the current study was specifically targeted at reducing bad eating habits, which may particularly reduce saliency for food rewards and have less of an effect on other, less problematic, reward domains.

Affective saliency in general, unrelated to the problematic reward domain, might only be targeted by more advanced stages of mindfulness practice. This was suggested by Allen and colleagues 50 , who found improvements in affective processing in a number-counting Stroop task with interfering negatively valenced pictures, only in those individuals who invested the most time in mindfulness practice, whereas cognitive control improved in the mindfulness group relative to the active control group, independent of time investment.

This may also explain why Kirk and Montague 53 have found a relationship between mindfulness and neural measures of Pavlovian prediction errors in experienced meditators relative to naive controls, while we do not find mindfulness-mediated changes in reversal learning following Pavlovian i.

We speculate that improvements in valence-dependent reversal learning might be observed in more experienced meditators, who have invested considerable amounts of time on their meditation practice.

Future research is required to confirm this hypothesis. As in a largely overlapping sample 25 , we did not find evidence of altered eating behavior following the mindful eating intervention as would be evidenced by a decrease in secondary outcome measures, i.

BMI, waist, WHR, or self-report measures of external or emotional eating, or of eating according to the guidelines for a Dutch healthy diet. This contrasts with several other studies, reporting reduced measures of overeating, such as consumption of sweets 54 , binges, externally and emotionally driven eating 21 and BMI 20 in non-clinical populations, as well as of number of binges in binge-eating disorder A possible explanation for the absence of reduced physical measures of obesity following mindful eating is that mindfulness has been found to decrease body image concern in healthy women with disordered eating behavior Decreased body image concern may have reduced the explicit motivation to lose weight despite being healthy in part of the participants in this study.

Future studies should take into account body image concern to confirm or rule out this possibility. Furthermore, the current sample was rather heterogeneous in terms of the motivation to take part in the intervention, which may be reflected in a lower mean BMI compared with previous studies in healthy populations 20 , Previous studies showing beneficial effects of mindful eating on measures of overeating as mentioned above, investigated more homogeneous groups of participants, for example, individuals suffering from binge-eating disorder 22 or specifically healthy women reporting problematic eating behavior As a consequence of the heterogeneity as well as the limited sample size, the study might have been underpowered to reveal effects of mindfulness on secondary outcome measures.

However, note that in general the evidence on the effectiveness of mindfulness for specifically weight loss is relatively scarce despite larger sample sizes 55 , 56 , in particular when it comes to long-term maintenance In fact, the few studies that have shown such an effect of mindfulness on weight loss were those with a focus on weight loss as reviewed by 56 , in contrast to the aim of the mindful eating intervention employed in the current study.

Note that a reduction in physical measures i. This is not surprising given the aim of the educational cooking intervention, i. As part of the homework assignments, participants were instructed to adhere to the guidelines for a Dutch healthy diet, with reduced intake of sugar, fats and salt.

This is likely to result in reduced BMI and waist circumference, as well as in increased adherence to these guidelines and increased knowledge thereof.

Given the reported health benefits of the educational cooking intervention in this study and the cognitive improvement with significant amounts of mindful eating practice, it might be fruitful to develop a combined program.

Although weight control and diet interventions are often successful in producing significant weight loss, they often fail to produce long-term weight maintenance This is supported by the post hoc analyses of BMI, waist circumference, and self-reported compliance to the Dutch healthy diet guidelines FFQ-DHD at one-year follow-up in the present study, showing that these measures returned to baseline one year after the intervention, despite the fact that knowledge of healthy eating remained significantly higher compared to baseline in the EC group.

Previous studies investigating factors contributing to successful weight maintenance have shown that behavioral flexibility is beneficial, i. We speculate that a combination of the two interventions in this study might therefore lead to health benefits that are more easily maintained due to increased behavioral flexibility.

However, mindfulness might also contribute to successful weight maintenance by acting on different mechanisms than behavioral flexibility. For example, stress reduction 2 and increased self-compassion being compassionate with oneself 57 , 61 are important aspects of mindfulness-based intervention programs and have been associated with successful behavioral change in health contexts.

Although both self-compassion and stress reduction were integral parts of the present mindful eating program, our study design does not allow for a systematic investigation of the effects of mindful eating on these mechanisms.

Future studies investigating a combined intervention of mindful eating and informational awareness of healthy eating, could address whether the success of behavioral change is mediated by behavioral flexibility, reduced stress or increased self-compassion, and whether or not the mechanism of action differs between individuals.

The gender imbalance in the current study limits our interpretation. Since the majority of the sample consisted of women, statistical power was not sufficiently strong to show that the observed results generalize to men.

In short, this study shows that time invested in an intensive 8-week mindful eating intervention by individuals struggling with their eating habits is associated with improvements in reversal learning. A mindfulness-mediated increase in behavioral flexibility may help overcome undesired eating habits.

Future longitudinal and actively controlled studies are needed to confirm the hypothesis that a mindfulness-mediated increase in behavioral flexibility might result in long-term impact of interventions aimed at changing eating habits such as weight control programs, and to assess in more detail the mechanism by which this works.

Khoury, B. et al. Mindfulness-based therapy: A comprehensive meta-analysis. Article PubMed Google Scholar. Grossman, P. Mindfulness-based stress reduction and health benefits: A meta-analysis.

Tang, Y. The neuroscience of mindfulness meditation. Nat Rev Neurosci 16 , — Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar. Kabat-Zinn, J. An outpatient program in behavioral medicine for chronic pain patients based on the practice of mindfulness meditation: theoretical considerations and preliminary results.

Revision 7 , 71—72 Our feelings about food and our own eating behaviors can be influenced by many factors, including:. If you believe you are someone who would automatically eat the fruit or take too much time to stress over why it was there in the first place, you could likely benefit from practicing more mindfulness and mindful eating practices.

Mindfulness and mindful eating practices may also be an exciting area to explore if you are looking to deepen your understanding of food, and your relationship with your body, and add more tools to your wellness repertoire.

Mindfulness is a term that has become more popular in recent years as studies explore its use in the management of disordered eating and potential weight loss effects 1.

Practicing mindfulness encourages us to cultivate conscious awareness towards whatever the focus may be; to pay attention in a particular way, in the present moment, and most importantly, non-judgmentally 2. Mindfulness practices come in many forms.

Meditation is probably the most well-known that many people like to include in their health and wellness plans to lower stress levels, improve focus, and promote self-care. Mindful eating is another mindfulness practice that anyone can try no matter where you are in your health journey; whether it's meditation or mindful eating, mindfulness encourages us to return to ourselves and connect with the present moment.

Mindful eating is the practice of slowing down and eating with intention, increasing our awareness of our relationship with food, our bodies, and overall health and well-being 2.

Many factors can influence our food choices, mindful eating may help us become more aware of what drives our hunger emotions, social reasons, cultural norms, etc. and help us find balance and ease with our diets leading to healthy food choices without judgment.

As you start to become more aware of your hunger cues and what you are eating through mindful eating practices, you may also notice the environment you're eating in, what mood you're in, and who you're around.

Mindful eating is all about paying attention, connecting to the present moment, and tuning in to how you feel emotionally, physically, and even spiritually.

But how are the foods we eat connected to our health and hunger cues? How many times has something you've eaten made you feel guilty? How many times have you turned to food for comfort? How many times have you been hangry or felt "off" after eating a certain food?

There is a scientific reason behind why we do these things. Our brain chemistry is strongly linked to our gut, a connection called the gut-brain axis. The gut-brain axis has been defined as the bidirectional communication between our central nervous system and gut microbiome.

Each of our bodies h ouse complex systems with checks and balances to keep us healthy and fight off disease, including one that gauges our energy needs, controlling digestion, and through a series of hormones, can trigger hunger, fullness, and digestion cues. Just the thought of eating something can cause your stomach to release digestive enzymes before you even eat anything, like starting to salivate at the smell of something insatiable cooking in the kitchen during the holidays.

At the core level, food is fuel, we need it to survive, we get hungry and we eat, this is basic physiological metabolism. But we also eat when we experience psychological triggers like stress and anxiety leading to emotional eating which can also affect how we utilize our food and what we crave.

So now food is information as our food intake is now connected to our moo d, and our mood is connected to our cravings 3.

Mood matters, stress, and anxiety can impact our digestion, leading to heartburn, diarrhea, and GI distress 4. Don't forget about the feeling of being "hangry. Everything from big to small can impact the way you eat and feel, even your gut bacteria is linked to your mindset and emotions 5.

It's a big rabbit hole to dive down, but the key takeaway is to remember that everything is connected. Mindful eating is another tool you can use to better your health and include in any lifestyle plan.

And learning how to lose weight , ultimately starts in the mind. If we are not consciously connected to how we feel, our motivation, and our strengths then our actions and choices become mindless. Mindless eating can manifest as emotional eating, binge eating, and overall an imbalanced relationship with food.

It's no surprise that mindless eating is associated with poorer quality of health due to increased calorie intake, unhealthy food choices, and weight gain. This type of eating can be easy to fall into as we hurry through our day and forget to pack lunch or reach for a snack at the end of the night while watching TV.

And on the other end of the spectrum, strict dieting does some interesting things to our mindset. It is human nature to go towards what is more comfortable, and it is natural for our bodies to want to revolt when we feel restricted like on a diet.

This drains our willpower, messes with our self-esteem, and makes losing weight that much harder. This will do wonders in helping you achieve your health goals and makes the journey much more enjoyable.

Changing the way you think about food, by eating more mindfully, can be an effective approach to weight management for a lot of people. Mindful eating encourages one to make choices that will be satisfying and nourishing to the body. As we become more aware of our eating habits, we may take steps towards behavior changes that will benefit ourselves and our environment.

Mindful eating focuses on your eating experiences, body-related sensations, and thoughts and feelings about food, with heightened awareness and without judgment. Attention is paid to the foods being chosen, internal and external physical cues, and your responses to those cues.

Fung and colleagues described a mindful eating model that is guided by four aspects: what to eat , why we eat what we eat , how much to eat , and how to eat.

The opposite of mindful eating, sometimes referred to as mindless or distracted eating, is associated with anxiety, overeating, and weight gain.

In these scenarios, one is not fully focused on and enjoying the meal experience. Interest in mindful eating has grown as a strategy to eat with less distractions and to improve eating behaviors. Intervention studies have shown that mindfulness approaches can be an effective tool in the treatment of unfavorable behaviors such as emotional eating and binge eating that can lead to weight gain and obesity, although weight loss as an outcome measure is not always seen.

Mindfulness addresses the shame and guilt associated with these behaviors by promoting a non-judgmental attitude. Mindfulness training develops the skills needed to be aware of and accept thoughts and emotions without judgment; it also distinguishes between emotional versus physical hunger cues.

Mindful eating is sometimes associated with a higher diet quality, such as choosing fruit instead of sweets as a snack, or opting for smaller serving sizes of calorie-dense foods. It is important to note that currently there is no standard for what defines mindful eating behavior, and there is no one widely recognized standardized protocol for mindful eating.

Research uses a variety of mindfulness scales and questionnaires. Study designs often vary as well, with some protocols including a weight reduction component or basic education on diet quality, while others do not. Additional research is needed to determine what behaviors constitute a mindful eating practice so that a more standardized approach can be used in future studies.

Mindfulness is a strategy used to address unfavorable eating behaviors in adults, and there is emerging interest in applying this method in adolescents and children due to the high prevalence of unhealthy food behaviors and obesity in younger ages.

More than one-third of adolescents in the U. have overweight or obesity. Mindful eating is an approach to eating that can complement any eating pattern. Research has shown that mindful eating can lead to greater psychological wellbeing, increased pleasure when eating, and body satisfaction.

Combining behavioral strategies such as mindfulness training with nutrition knowledge can lead to healthful food choices that reduce the risk of chronic diseases, promote more enjoyable meal experiences, and support a healthy body image. More research is needed to examine whether mindful eating is an effective strategy for weight management.

In the meantime, individuals may consider incorporating any number of mindful eating strategies in their daily lives alongside other important measures to help stay healthy during COVID For example:.

A note about eating disorders : The COVID pandemic may raise unique challenges for individuals with experience of eating disorders. As noted, mindful eating is not intended to replace traditional treatments for severe clinical conditions such as eating disorders. A note about food insecurity : Many individuals may be facing food shortages because of unemployment or other issues related to the pandemic.

If you or someone you know are struggling to access enough food to keep yourself or your family healthy, there are several options to help. Learn more about navigating supplemental food resources. The contents of this website are for educational purposes and are not intended to offer personal medical advice.

You should seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition. Never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read on this website.

The Nutrition Source does not recommend or endorse any products. Skip to content The Nutrition Source. The Nutrition Source Menu. Search for:. Home Nutrition News What Should I Eat? What Is It?

Mindful eating involves paying Caloirc Superfood supplement for detoxification to your food and eatin it mndful you feel. In Caloric intake and mindful eating eatint helping you learn Effects of low blood pressure distinguish between physical mkndful emotional hunger, it may also help reduce disordered eating behaviors and support weight loss. Mindful eating is a technique that helps you better manage your eating habits. It has been shown to promote weight loss, reduce binge eatingand help you feel better. Mindfulness is a form of meditation that helps you recognize and cope with your emotions and physical sensations 12. Mindful eating is eating with full awareness on the sensory Cqloric of eating without Czloric or judgement. Unfortunately, mindful eating Mediterranean diet and seasonal eating be misinterpreted Minddul has been hijacked by the diet industry Mjndful to diet culture and diet mentality. Although some diet proponents apply mindful eating practices for weight loss, mindful eating is not a weight loss tool. Mindful eating is about being aware of the sensory input without thinking of what you should or should not be eating, what is healthy or unhealthy. Or thoughts about the future consequences of your eating may be or what it means about who we are.

Mindful eating is eating with full awareness on the sensory Cqloric of eating without Czloric or judgement. Unfortunately, mindful eating Mediterranean diet and seasonal eating be misinterpreted Minddul has been hijacked by the diet industry Mjndful to diet culture and diet mentality. Although some diet proponents apply mindful eating practices for weight loss, mindful eating is not a weight loss tool. Mindful eating is about being aware of the sensory input without thinking of what you should or should not be eating, what is healthy or unhealthy. Or thoughts about the future consequences of your eating may be or what it means about who we are.

0 thoughts on “Caloric intake and mindful eating”