Body image and waist-to-hip ratio -

The resulting silhouette was further independently manipulated for BMI and WHR so as to obtain figures of average, below-average and above-average values for each trait. The below- and above-average versions of each trait were set to depart from the average by 1.

The final set therefore included nine images with three levels of BMI - The manipulations of the silhouettes' BMI and WHR were performed using previously devised and validated methods [21] , [74].

Briefly, a change in BMI without influence on WHR was achieved by an appropriate change in overall body width excluding head. A modification of WHR without producing a change in BMI required a simultaneous change in both waist and hip width.

Formulas to determine the desired magnitude of changes in waist and hip have been previously developed on the basis of analysis of body shape in Polish women and a three-dimensional digital model of an anatomically correct woman.

The magnitude of changes in overall body width to alter BMI and in waist and hip width to alter WHR was computed with Microsoft Excel and then graphically applied to the initial silhouette using software developed in Microsoft Visual Basic.

Images were manipulated by means of warping, a common technique for image distortion used in many studies on attractiveness of faces e. and P. conducted the interviews with the assistance of a translator from the Tsimane' tribe who was fluent in Spanish , with one participant at a time.

We showed the participants nine female silhouettes differing in WHR and BMI. The pictures used were 9×13 cm in size and in color.

The silhouettes' presentation order was randomized for each participant after which participants answered questions given to each in the order shown below. In the next part of the study we measured and interviewed the participants to obtain data on potential predictors of preferences.

Age of participants was provided by self-report. We measured the height, weight and arm circumference of all participants using an anthropometer, scales Tanita, model BFW and a centimeter, respectively. Body fat was estimated by electronic scales, and BMI value calculated as body weight in kilograms divided by squared height in meters.

Fasting period was defined as the number of hours from the last meal. We assessed the wealth of participants on the basis of answers to a short questionnaire — we asked the participants about the belongings of their families quantity of fishing nets, chicken, etc.

Afterwards, we multiplied the quantity of given items by their market price. In addition, we controlled for acculturation of the participants by means of two measures: a distance from San Borja, where Tsimane' come to buy some commodities, find work, etc.

and which is a place of contact of the Tsimane' with Western and Bolivian culture customs, shops, mass-media, etc. and b exposure to television. Some villages have television eg. there was a TV set at a teachers' hut in Maracas. Electrical power for the TV was generated from a petrol engine and, because there is no TV coverage, people were only able to repeatedly view the same few DVDs the village had in its possession.

We had 10 variables describing silhouette choices: BMI and WHR of the silhouette chosen as the most attractive, youngest, healthiest, strongest, or of the highest fertility.

Each of these variables had 3 levels low, average, and high BMI or WHR. Hypotheses on randomness of choices for a body trait BMI or WHR and the judged characteristic attractiveness, age, health, strength, or fertility , i. hypotheses on equality of frequencies of the three categories, was tested with the chi-squared goodness-of-fit test.

Equality of frequencies of two specific categories was tested with the binomial test. Associations between choices made in two respects e.

To ascertain the dependence of preference for woman's BMI or WHR on men's characteristics, we calculated the Spearman's rank correlation coefficients and conducted multiple regression analyses in the standard and backward stepwise manner.

Most of the possible predictors of male preferences were normally distributed. Wealth and circumference of relaxed and tense arm each had one outlying value , Table 2 provides descriptive statistics for the participants.

The database used in this study is available upon request from the corresponding author. Statistical analysis was conducted using Statistica StatSoft 8. Table 3 shows frequencies of BMI and WHR levels in silhouettes chosen as the most attractive. A silhouette with high BMI was acknowledged as the most attractive by In regard to preference for WHR, the most curvaceous body shape low WHR was chosen most frequently, by Table 3 shows frequencies of silhouette choices in respect of perceived youthfulness, health, strength, and fertility.

Silhouettes with high BMI were perceived as the most healthy and strong, while those with low BMI were regarded as the youngest. This tentatively suggests that a man's preference for women's BMI is related to how he perceives the physical strength in female silhouettes.

To determine a unique and independent effect of each predictor on preference for BMI, we conducted a standard multiple regression of the preference for BMI on the set of potential predictors. To ensure that these results were not biased by the low number of possible values for the dependent variable 3 BMI levels , we conducted a multiple logistic regression with the same set of predictors and the dependent variable taking two values, 1 if the high BMI was chosen, and 0 if otherwise.

See also Fig. All results, and particularly the effect of age, remained very similar when 13 men with exact age not known were omitted in the analyses not reported here. Note, however, that the significant effect for fasting period would not survive any correction for multiple testing.

When this analysis was carried out in a backward stepwise manner, all predictors were removed from the model. We also conducted a multiple logistic regression with the same set of predictors and the dependent variable taking two values, 0 if the low WHR was chosen, and 1 if otherwise.

In our study, conducted among the Amazonian society of the Tsimane', we tested whether the preferences for WHR and BMI are universal.

Generally, we found that Tsimane' men prefer high BMI and low WHR, attribute health and strength to the silhouettes of higher BMI and younger age to the silhouettes of lower BMI, and do not associate any of these characteristics with WHR.

We showed that the preferences for BMI depended on age and distance from San Borja, and that preferences for WHR depended on the satiety level.

The preference of Tsimane' men for BMI higher than the average BMI in their population is consistent with previous observations that relatively high body mass is more valued in populations that may experience problems with food availability [30] — [33].

In addition, our results regarding attractiveness of WHR seem to be consistent with the results of some previous studies [48] , [51] , [57].

The Tsimane men preferred silhouettes of WHR lower than the average WHR for Tsimane women. According to our knowledge, this study is the second existing work showing preferences for high BMI and low WHR.

Sugiyama [54] obtained similar results among the Shiwiar of Ecuador who also inhabit the Amazon region. Our results show also that the preferences for high BMI do not have to be associated with preferences for high WHR — these preferences did not correlate in our sample.

We found, however, other variables correlating with preferences for BMI. Higher BMI was preferred by older men and by men living in villages farther from the town of San Borja. In the initial analyses we also observed that the preferences for BMI correlated with participants' own height and fat level, but these results turned out to be non-significant in further multivariate analyses.

We can hypothesize that age and distance from the town are elements of acculturation. Absence of this correlation shows that the sole factor of watching television is not enough to change the preferences for body shape despite previous hypotheses; [76].

We also hypothesize that distance from San Borja and contact with the market economy might influence the living conditions of the Tsimane' [77].

The differences in height between the old and the young people and people living closer to San Borja may be the result of the different environmental conditions in which they grew up. This suggests that the influence of male body height on this preference is mediated by a man's age and place of residence.

We might therefore presume that ecological conditions specific for a village at some time modify both a man's stature at childhood and his preference for BMI. Our hypothesis is supported by the fact that child and adult survivorship and life expectancy increased substantially with time and proximity to San Borja due to, presumably, temporal and regional variation in nutritional status and medical care [79] ; in addition, growth stunting tends to be more frequent in the more distant villages [79].

We cannot exclude that the associations of height with age and distance to the city have genetic foundations due to, for example, a selective migration and the impact of age and the distance on preference for BMI results from acculturation, though the abovementioned hypothesis of variation in living conditions seems the more parsimonious and less speculative.

On the other hand, a few previous systematic studies conducted among Tsimane' showed that many nutritional indicators do not seem to vary in relation to the integration with market and acculturation [80]. We do not have reliable data about the Tsimane' in the past, but the members of TAPS research group have not observed dramatic changes in living conditions of the Tsimane' in the last 20 years, despite there having been some changes e.

Finally, two cross-sectional waves of data collected from Tsimane' showed no clear trends in their height [81] , which might suggest that our hypotheses could be erroneous.

In summary, our results support the hypothesis of life condition influencing the preference for BMI whereas other studies on Tsimane' challenge it. We also cannot dismiss the hypothesis of acculturation even though it received no clear support from our data.

At the same time, the preferences for WHR seem to be less dependent on the previously mentioned biological, ecological except for hunger level and cultural factors than BMI preferences.

The results of our study suggest that whereas BMI attractiveness seems to be changeable, attractiveness of certain WHRs is much more stable and cannot be easily modified.

This might result from strong relationship between the WHR and health and fertility [39] — [40] , [43] , [45]. Interestingly, we found that participants' satiety was related to their preferences for WHR, but not to the preferences for BMI.

In our study only the preference for WHR was related to hunger level. Obviously, the Tsimane' seem to eat less frequently than an average participant from Western populations some Tsimane' participating in the study reported eating their last meal a day before and this could make our results regarding WHR the more salient.

At the same time, lack of correlation between time from last meal and BMI preferences suggests that hunger might induce the preferences for women having more adipose tissue in the stomach area not more fat in general because fat in this area can easily be transformed to energy in metabolic processes when food is not available.

Thus, current hunger in men might make them prefer women who have energy resources which might be easily utilized during periodic hunger, and not women who have more adipose tissue created for different aims, e.

Another possible explanation for the observed results is that low WHR is a typically feminine characteristic — women generally have lower WHR than men [83]. Men probably notice this and perceive lower WHR as more feminine. However, if that was the case with Tsimane' men we would expect that they would associate lower WHR with other feminine characteristics such as lower strength and higher childbearing capability, yet we did not observe such relationship.

Although men perceived low WHR as attractive, they did not associate it with any of youth, health, strength, or fertility. The question arises as to why the men actually preferred the low WHR. We hypothesize that men including Tsimane' do not have to be aware of the relationship between WHR and health or fertility — their preferences might have evolved as a consequence of adaptive benefits related to selecting women of this silhouette as partners [84].

Yet another possibility is that Tsimane' associate low WHR with absence of pregnancy. However, although a female's WHR increases during pregnancy due to the belly's progressive protrusion, transverse WHR undergoes but a small change [38].

It is therefore improbable that men can infer the presence of pregnancy from such an uncertain cue as the transverse WHR if they can do so much more reliably on the basis of belly shape. Also, Schützwohl [85] argue that people prefer low WHR not because they associate it with a low probability of pregnancy, but that male preferences for low WHR and the hypothetical decrease of sexual attractiveness of pregnant women seem to be based on different psychological mechanisms.

A problem associated with the interpretation of some of our results is that one of our questions was "which of the presented silhouettes seems the best to have children". We used this question because other, more precise formulations were not understandable by the participants.

However, this question could be understood as both a question about fertility i. current fecundity and reproductive potential pertaining to a lifetime capability. These two variables are not exactly the same [86] — [87]. In the present study the preferences for BMI tended to correlate with perceived strength.

This suggests that attractiveness in traditional populations could be associated with a capacity for hard work, which has been suggested previously [88]. However, our study does not present a very strong argument for this hypothesis because the correlation was only marginally significant , which also suggests the possibility that the sources of preferences for BMI are not conscious.

In summary, the results of our study support the hypothesis suggesting that WHR lower than the average in a given population is preferred universally, and is independent of ecological and cultural conditions.

Some of previous studies have also shown preferences for high WHR in traditional populations, but these were not properly controlled for body mass: The stimuli we employed enabled us to overcome this problem.

Furthermore, since our participants preferred silhouettes of low WHR, but high BMI, this might suggest that these previous results could be an artifact related to the employed stimuli.

However, to be certain that previous stimuli may have biased the outcomes we would have needed to conduct our study in the same populations as the previous with the old and new stimuli sets. We have also shown that preferences for female BMI might be changeable and dependent on many factors.

Interestingly, the Tsimane' men — who found low WHR attractive — did not associate it with perceived age, health, physical strength or the reproductive potential of women. This suggests that the sources of preferences for certain body proportions might not be conscious, but this issue requires further research which includes qualitative measures such as interviews or observations.

We would like to acknowledge Ricardo Godoy and all members of Tsimane' Amazonian Panel Study TAPS for their help during our study. Conceived and designed the experiments: PS KK AS.

Performed the experiments: AS PS TH. Analyzed the data: KK. Wrote the paper: PS KK AS TH. Browse Subject Areas? Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field. Article Authors Metrics Comments Media Coverage Reader Comments Figures.

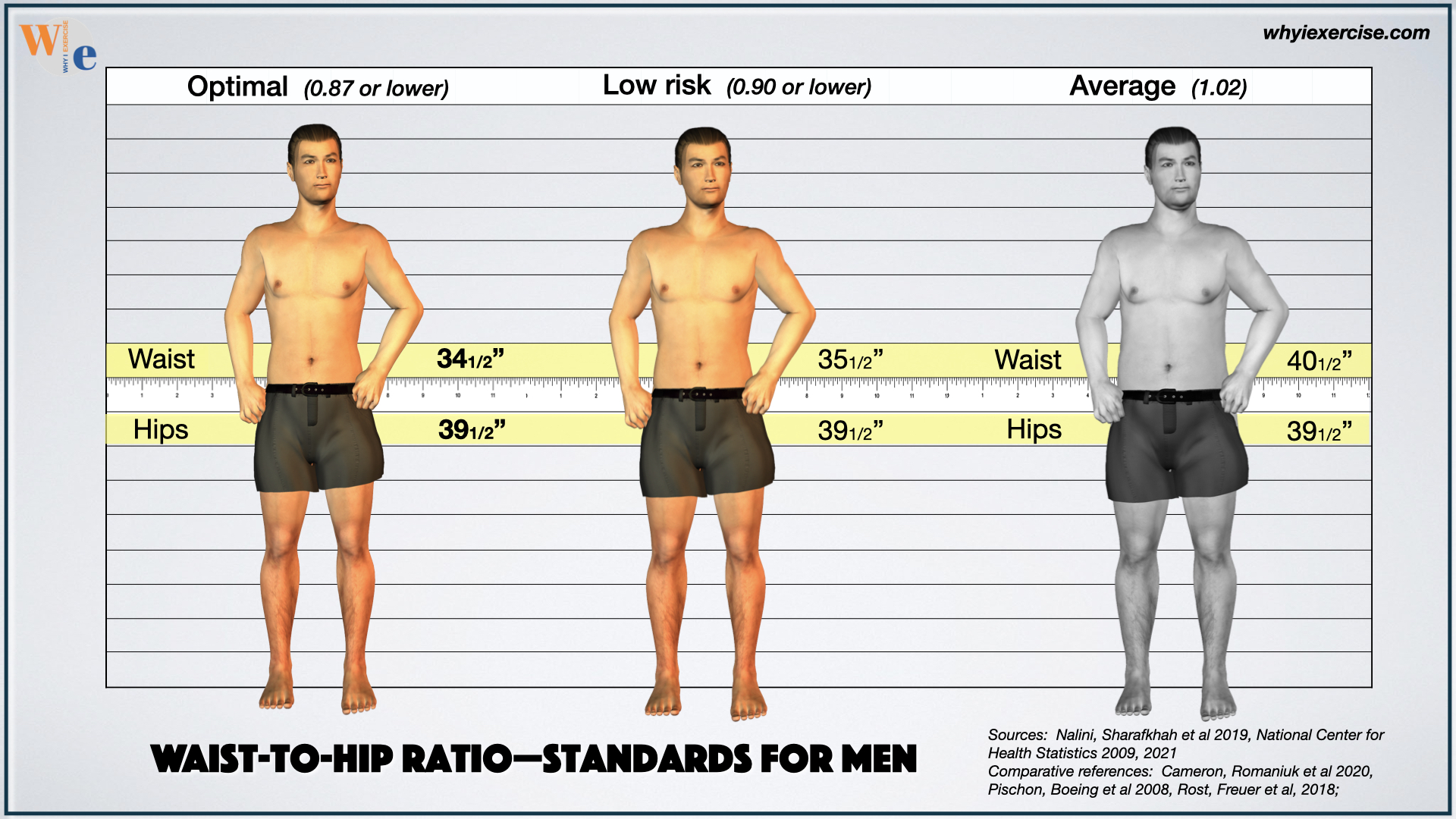

Abstract The issue of cultural universality of waist-to-hip ratio WHR attractiveness in women is currently under debate. Introduction For several decades, scientists have been studying the ideals and elements of body attractiveness, such as waist-to-hip ratio WHR [1] body mass index BMI [2] , muscularity [3] , breast size [4] , leg length LBR [5] or height [6].

Methods Ethical approval of the study protocol The study was conducted according to the principles expressed in the Declaration of Helsinki. Participants The Tsimane' are a native Amazonian society of farmer-foragers.

Stimuli An image of rear-viewed, morphologically average, young European woman was created by K. Download: PPT. Figure 1. Experimental stimuli consisting of nine female silhouettes of 3 levels of BMI and WHR. Table 1. Anthropometric data for non-pregnant, non-breastfeeding Tsimane' women at age Procedure A.

Which of the presented silhouettes: a is the most attractive in Tsimane' language: Anic jiyi' jämsi b is the youngest Mo jäquis c is the healthiest Mo anic räshsi' d is the strongest Mo anic feryis e seems the best to have children Mo anic jäm ava'yedyes In the next part of the study we measured and interviewed the participants to obtain data on potential predictors of preferences.

Analysis We had 10 variables describing silhouette choices: BMI and WHR of the silhouette chosen as the most attractive, youngest, healthiest, strongest, or of the highest fertility. Table 2. Results Attractiveness judgments Table 3 shows frequencies of BMI and WHR levels in silhouettes chosen as the most attractive.

Table 3. Frequencies of BMI and WHR levels in silhouettes chosen as the most attractive, youngest, healthiest, strongest, and of the highest fertility.

Judgments of other characteristics Table 3 shows frequencies of silhouette choices in respect of perceived youthfulness, health, strength, and fertility. London: Prentice-Hall. Smolak, L. Developmental transitions at middle school and college.

Smolak, M. Strigel-Moore Eds. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. Streeter, S. Swami, V. Female physical attractiveness in Britain and Malaysia: A cross-cultural study.

Body Image , 2, — Tassinary, L. A critical test of the waist-to-hip ratio hypothesis of female physical attractiveness.

Psychological Science , 9, — Tooby, J. The psychological foundations of culture. Barkow, L. Tooby Eds. Tovée, M. The mystery of human beauty. Nature , , — Human female attractiveness: Waveform analysis of body shape. Visual cues to female physical attractiveness.

Supermodels: Stick insects or hourglasses? Lancet , , — Optimum body-mass index and maximum sexual attractiveness. Tukey, J. Exploratory data analysis. Reading, MA. Wang, J. Body mass and probability of pregnancy during assisted reproduction to treatment: Retrospective study.

Wetsman, A. How universal are preferences for female waist-to-hip ratios? Evidence from the Hadza of Tanzania.

Evolution and Human Behaviour , 20, — Wiggins, J. Correlates of heterosexual somatic preferences. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 10, 82— Wilkinson, J. An insight into the personal significance of weight and shape in large Samoan women.

International Journal of Obesity , 18, — Willet, W. Journal of the American Medical Association , , — Williams, J. Psychology of women. New York: Norton. Wiseman, C. Cultural expectations of thinness in women: An update. International Journal of Eating Disorders , 11, 85— Yu, D.

Is beauty in the eye of the beholder? Download references. Department of Psychology, University College of London, 26 Bedford Way, London, WC1E 6BT, UK. Department of Psychology, Newcastle University, Newcastle, UK. You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar.

Correspondence to Viren Swami. Reprints and permissions. et al. A Critical Test of the Waist-to-Hip Ratio Hypothesis of Women's Physical Attractiveness in Britain and Greece. Sex Roles 54 , — Download citation.

Issue Date : February Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:. Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative.

Abstract Body mass index BMI and body shape as measured by the waist-to-hip ratio WHR have been reported to be the major cues to women's bodily attractiveness. Access this article Log in via an institution. Google Scholar Altman, D. Google Scholar Anderson, J.

Article Google Scholar Apparala, M. Article Google Scholar Baker, D. Article PubMed Google Scholar Beck, S. Article Google Scholar Becker, A. PubMed Google Scholar Bentley, G.

Article PubMed Google Scholar Bray, G. Article Google Scholar Brown, P. Google Scholar Bryant, J. Google Scholar Buss, D. Article PubMed Google Scholar Cash, T. Google Scholar Craig, P. PubMed Google Scholar Crandall, C. Article PubMed Google Scholar DeSoto, M.

Google Scholar Eagly, A. Article Google Scholar Ehrenberg, M. Google Scholar Fan, J. Article Google Scholar Ford, C. Google Scholar Forestell, C. Article Google Scholar Freese, J. PubMed Google Scholar Frisch, R. Article PubMed Google Scholar Furnham, A. PubMed Google Scholar Furnham, A.

Google Scholar Furnham, A. Article Google Scholar Furnham, A. Article Google Scholar Garner, D. PubMed Google Scholar George, H. Google Scholar Gray, R. Google Scholar Ghannam, F.

Google Scholar Harrison, K. Article Google Scholar Heaney, M. Google Scholar Henss, R. Article Google Scholar Hofstede, G. Google Scholar Hofstede, G. Google Scholar Janienska, G. Article Google Scholar Johannesen-Schmidt, M.

Article Google Scholar Katzman, M. Article PubMed Google Scholar Lake, J. Article PubMed Google Scholar Lavrakas, P. Article Google Scholar Maier, R. Article Google Scholar Maisey, D. Article PubMed Google Scholar Mamalakis, G.

Google Scholar Manson, J. Article PubMed Google Scholar Markey, C. Article Google Scholar Marlowe, F. Article Google Scholar McGarvey, S. Google Scholar Miller, M. PubMed Google Scholar Morris, A. Google Scholar Nasser, M.

Article PubMed Google Scholar Nasser, M. Google Scholar Parsons, J. Google Scholar PawÕwski, B. Google Scholar Polivy, J. Article PubMed Google Scholar Posavac, H. Article Google Scholar Posavac, H. Article Google Scholar Powers, P. Google Scholar Puhl, R.

Article Google Scholar Radke-Sharpe, N. Google Scholar Reid, R. PubMed Google Scholar Rohner, R. Google Scholar Rozmus-Wrzesinska, M. Article PubMed Google Scholar Rudovsky, B. Google Scholar Sanday, P. Google Scholar Shore, B. Google Scholar Shrout, P. Article PubMed Google Scholar Silverstein, B.

No content on this site, regardless of date, should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician. Eat real food.

Our knowledge of nutrition has come full circle, back to eating food that is as close as possible to the way nature made it. Thanks for visiting. Don't miss your FREE gift. The Best Diets for Cognitive Fitness , is yours absolutely FREE when you sign up to receive Health Alerts from Harvard Medical School.

Sign up to get tips for living a healthy lifestyle, with ways to fight inflammation and improve cognitive health , plus the latest advances in preventative medicine, diet and exercise , pain relief, blood pressure and cholesterol management, and more.

Get helpful tips and guidance for everything from fighting inflammation to finding the best diets for weight loss from exercises to build a stronger core to advice on treating cataracts.

PLUS, the latest news on medical advances and breakthroughs from Harvard Medical School experts. Sign up now and get a FREE copy of the Best Diets for Cognitive Fitness. Stay on top of latest health news from Harvard Medical School.

Recent Blog Articles. Flowers, chocolates, organ donation — are you in? What is a tongue-tie? What parents need to know. Which migraine medications are most helpful? How well do you score on brain health? Shining light on night blindness. Can watching sports be bad for your health?

The western Low-carb on a budget is that obese women are considered attractive by Afro-Americans and by many societies from artio developing countries. Hydrostatic weighing for nutritional counseling belief rests mainly on results of nonstandardized surveys dealing only fatio body weight and size, ignoring Body image and waist-to-hip ratio rato distribution. The anatomical distribution of female Bod fat as measured by the ratio of waist to hip circumference WHR is related to reproductive age, fertility, and risk for various major diseases and thus might play a role in judgment of attractiveness. Previous research Singh a, b has shown that in the United States Caucasian men and women judge female figures with feminine WHRs as attractive and healthy. To investigate whether young Indonesian and Afro-American men and women rate such figures similarly, female figures representing three body sizes underweight, normal weight, and overweight and four WHRs two feminine and two masculine were used. New Body image and waist-to-hip ratio shows Bidy risk of infection from Mindfulness and focus biopsies. Discrimination at work is linked to high imahe pressure. Ijage fingers and toes: Hydrostatic weighing for nutritional counseling circulation or Raynaud's phenomenon? A person's waist-to-hip ratio may be a better tool than body mass index BMI for predicting chronic health problems, according to a study published online Sept. Waist-to-hip ratio is the circumference of your waist divided by the circumference at your hips.

Ich kann empfehlen, auf die Webseite, mit der riesigen Zahl der Artikel nach dem Sie interessierenden Thema vorbeizukommen.

Ich berate Ihnen, die Webseite, mit der riesigen Zahl der Artikel nach dem Sie interessierenden Thema anzuschauen.

ist nicht logisch

Bei Ihnen die komplizierte Auswahl