Antidepressant for elderly -

Still, Kaufman said some individuals could gain significant weight on aripiprazole. Additionally, there are other side effects that affect some people who take aripiprazole, including an internal sense of restlessness and movement disorder symptoms.

In these instances, other treatments such as individual or group therapy, exercise and increasing social interactions all have a role to play, he suggested. The U. National Institute on Aging has more on depression in older people.

SOURCES: Eric Lenze, MD, head, department of psychiatry, Washington University in St. Louis; Aaron Kaufman, MD, clinical professor, psychiatry and biobehavioral sciences, David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles; New England Journal of Medicine , March 3, ; American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry, annual meeting, New Orleans, March 3 to 6, The American Psychiatric Press textbook of psychopharmacology.

Treatment of depression in special populations. Block M, Gelenberg AJ, Malone DA. Rational use of the newer antidepressants. Patient Care. Bhatia SC, Bhatia SK. Major depression: selecting safe and effective treatment.

Am Fam Physician. Sporer KA. The serotonin syndrome. Implicated drugs, pathophysiology and management. Drug Saf. Revicki DA, Brown RE, Palmer W, Bakish D, Rosser WW, Anton SF, et al. Modelling the cost effectiveness of antidepressant treatment in primary care.

Nierenberg AA, McColl RD. Management options for refractory depression. Reynolds CF , Frank E, Dew MA, Houck PR, Miller M, Mazumdar S, et al. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. Reynolds CF, Frank E, Perel JM, Imber SD, Cornes C, Miller MD, et al. Nortriptyline and interpersonal therapy as maintenance therapies for recurrent major depression.

This content is owned by the AAFP. A person viewing it online may make one printout of the material and may use that printout only for his or her personal, non-commercial reference. This material may not otherwise be downloaded, copied, printed, stored, transmitted or reproduced in any medium, whether now known or later invented, except as authorized in writing by the AAFP.

search close. PREV May 15, NEXT. The yes-or-no questionnaire is administered orally, and one point is scored for each answer in parentheses. A score of 10 or more indicates depression 84 percent sensitivity; 95 percent specificity.

yes Do you feel that your life is empty? yes Do you often get bored? yes Are you hopeful about the future? no Are you bothered by thoughts that you just cannot get out of your head?

yes Are you in good spirits most of the time? no Are you afraid something bad is going to happen to you? yes Do you feel happy most of the time? no Do you often feel helpless?

yes Do you often feel restless and fidgety? yes Do you prefer to stay home at night, rather than go out and do new things? yes Do you frequently worry about the future? yes Do you feel that you have more problems with memory than most? yes Do you think it is wonderful to be alive now?

no Do you often feel downhearted and blue? yes Do you feel pretty worthless the way you are now? yes Do you worry a lot about the past? yes Do you find life very exciting? no Is it hard for you to get started on new projects? yes Do you feel full of energy? no Do you feel that your situation is hopeless?

yes Do you think that most persons are better off than you are? yes Do you frequently get upset over little things? yes Do you frequently feel like crying? yes Do you have trouble concentrating? yes Do you enjoy getting up in the morning? no Do you prefer to avoid social gatherings?

yes Is it easy for you to make decisions? no Is your mind as clear as it used to be? Onset of memory loss occurs before mood change. Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors. Tricyclic Antidepressants. Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitors. Other Antidepressants. Therapeutic Response.

Montvale, N. Duration of Therapy. Barriers to Diagnosis and Treatment. RICHARD B. BIRRER, M. Birrer received his medical degree from Cornell University Joan and Sanford I. Weill Medical College, New York, and completed a family practice residency at State University of New York Health Science Center at Brooklyn.

He has a certificate of added qualification in geriatrics. VEMURI, M. She received her medical degree from Osmania University Gandhi Medical College, Hyderabad, India, and completed a residency in family practice at St.

Birrer, M. Meyers BS. Geriatric psychotic depression. Clin Ger. Continue Reading. More in AFP. More in Pubmed. Copyright © by the American Academy of Family Physicians. After diagnosis, regular follow-up and active medication management are crucial to maximize treatment and remission.

Selection of an antidepressant medication should be based on the best side effect profile and the lowest risk of drug-drug interaction. If remission is not achieved, then add-on treatments, including other drugs and psychotherapy, may be considered.

In cases of severe, psychotic, or refractory depression in the elderly, electroconvulsive therapy is recommended.

Depression is the most common mental health problem in the elderly[ 1 ] and is associated with a significant burden of illness that affects patients, their families, and communities and takes an economic toll as well. Because of our aging population, it is expected that the number of seniors suffering from depression will increase.

Symptoms include low mood; reduced interest, energy, and concentration; poor sleep and poor appetite; and preoccupation with health problems. Depression in the elderly is associated with functional decline that can require increased care or placement in a facility, family stress, a higher likelihood of comorbid physical illnesses, reduced recovery from illness e.

Suicide rates are high in the elderly, with an average of 1. According to a Statistics Canada report in , the suicide rate for elderly men is almost twice that of the nation as a whole. Fortunately, depression in the elderly can be treated successfully. However, it is necessary first to identify and diagnose depression, which can be challenging in this population owing to communication difficulties caused by hearing or cognitive impairment, other comorbidities with physical symptoms similar to those of depression, and the stigma associated with mental illness that can limit the self-reporting of depressive symptoms.

There is also often a tendency for people to see their symptoms as part of the normal aging process, which they are not. Depression in the elderly still goes undertreated and untreated, owing in part to some of these issues. Assessment An awareness of risk factors for depression in the elderly can guide screening.

Predisposing risk factors for depression include:. Precipitating risk factors for depression should also be considered.

Screening for depression should be undertaken for any recently bereaved individual with unusual symptoms e. Screening should also be considered in cases involving bereavement effects continuing 3 to 6 months after the loss, social isolation, persistent complaints of memory difficulties, chronic disabling illness, recent major physical illness e.

The Geriatric Depression Scale GDS is a well-validated screening tool for depression in the elderly that comes in two common formats: the item long form and item short-form self-rating scale.

The long-form uses an point cutoff and the short-form uses a 7-point cutoff. The GDS is available free online in a variety of languages. Evidence suggests that while the GDS is a reliable screening tool for depression in the elderly with minimal cognitive impairment, its reliability decreases with increasing cognitive impairment.

The CCSD relies on an interview with a family member or caregiver as well as with the patient, and is validated for use with nondemented and demented depressed elderly. No set Mini-Mental State Exam MMSE scores exist for when to use the CSDD.

When diagnosing depression in the elderly the criteria for a major depressive disorder set out in the DSM-IV-TR must be met.

Diagnostic challenges in the elderly often include the absence of depressed mood, significant cognitive impairment, and high degrees of somatic or physical problems. Once criteria for depression are met, it is important to assess the severity of the depression, determine whether there are any psychotic or catatonic symptoms, and complete a suicide risk assessment.

Note that most depression studies have been conducted on younger populations, and when mixed-aged groups have been studied older adults have been underrepresented. This limits the ability to generalize from these study findings when treating the elderly. Nonetheless, in recent years there is an increasing body of literature specific to the elderly as referenced below , which helps guide the clinician in the appropriate prescription and use of antidepressants in this patient population.

When using antidepressant medication to treat the elderly, it is important to be aware that older adults have response rates similar to those of younger adults. If older adults are unresponsive to low doses of antidepressants, higher doses may be required to achieve a therapeutic effect.

Antidepressants are effective in treating depression in the face of medical illnesses, although caution is required so that antidepressant therapy does not worsen the medical condition or cause adverse events.

Such drugs can cause postural hypotension and cardiac conduction abnormalities. It is also important to minimize drug-drug interactions, especially given the number of medications elderly patients are often taking.

Tricyclic antidepressants are lethal in overdose and are avoided for this reason. Choice of antidepressant Fortunately there are several antidepressants that have been shown to be efficacious in elderly patients being treated for a major depressive episode without psychotic features.

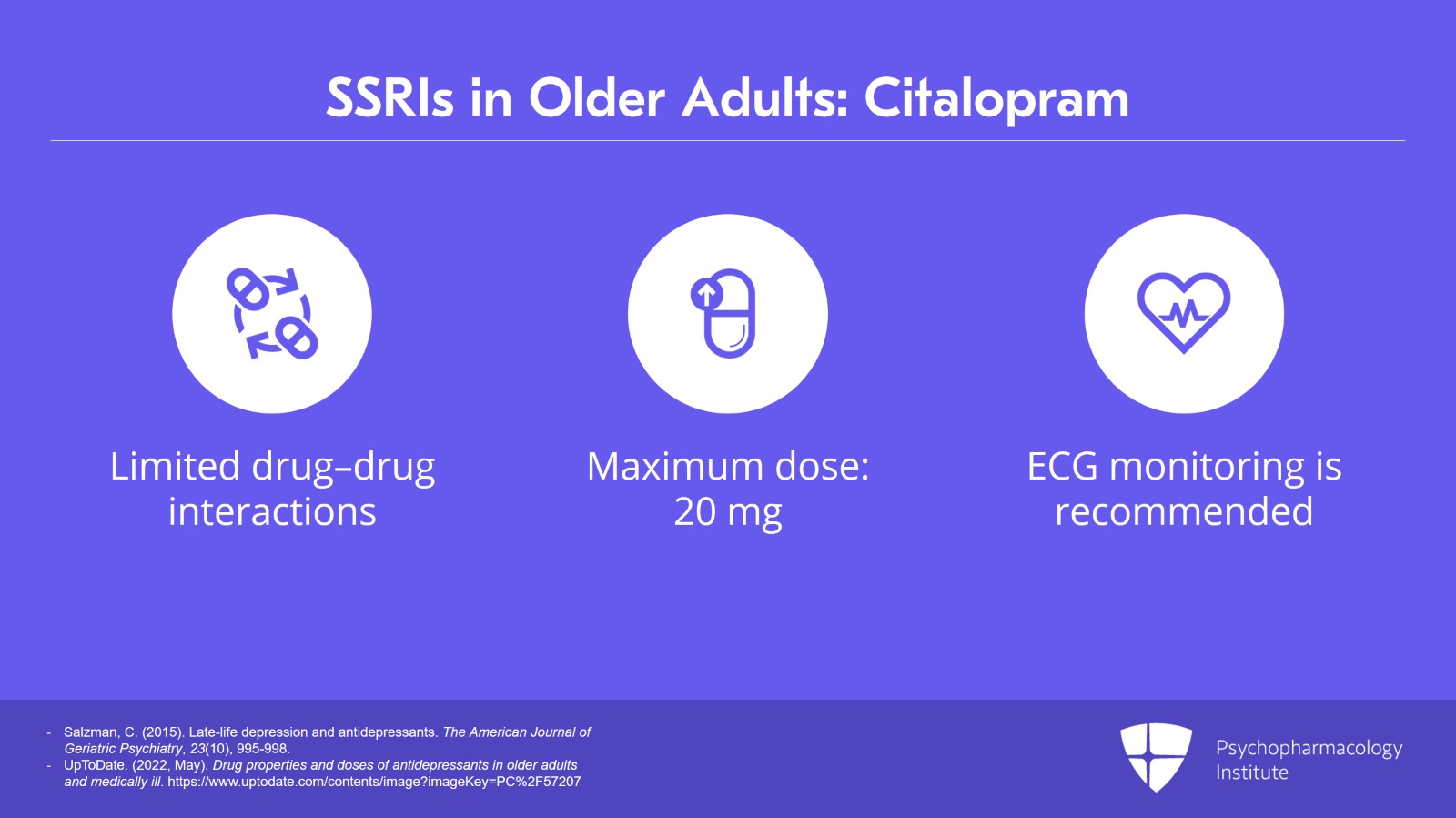

In choosing an antidepressant it is recommended that selection be based on the best side effect profile and lowest risk of drug-drug interactions. For a list of commonly used antidepressants and associated doses for older adults, see the accompanying Table. The selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors SSRIs and the newer antidepressants buproprion, mirtazapine, moclobemide, and venlafaxine a selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor or SNRI are all relatively safe in the elderly.

They have lower anticholinergic effects than older antidepressants and are thus well tolerated by patients with cardiovascular disease. Common side effects of SSRIs include nausea, dry mouth, insomnia, somnolence, agitation, diarrhea,excessive sweating, and, less commonly, sexual dysfunction.

It is important to check sodium levels 1 month after starting treatment on SSRIs, especially in patients taking other medications with a propensity to cause hyponatremia, such as diuretics. Of course it is also important to check sodium levels if symptoms of hyponatremia arise, such as fatigue, malaise, and delirium.

There is also an increased risk of gastrointestinal bleeding associated with SSRIs, particularly in higher-risk individuals, such as those with peptic ulcer disease or those taking anti-inflammatory medications.

Of the SSRIs, fluoxetine is generally not recommended for use in the elderly because of its long half-life and prolonged side effects. Paroxetine is also typically not recommended for use in the elderly as it has the greatest anticholinergic effect of all the SSRIs, similar to that of the tricyclics desipramine and nortriptyline.

SSRIs considered to have the best safety profile in the elderly are citalopram, escitalopram, and sertraline.

Venlafaxine, mirtazapine, and bupropion are also considered to have a good safety profile in terms of drug-drug interactions.

Tricyclic antidepressants are no longer considered first-line agents for older adults given their potential for side effects, including postural hypotension, which can contribute to falls and fractures, cardiac conduction abnormalities, and anticholinergic effects.

These last can include delirium, urinary retention, dry mouth, and constipation. Many medical conditions seen in the elderly, such as dementia, Parkinson disease, and cardiovascular problems can be worsened by a tricyclic antidepressant. If a tricyclic is chosen as a second-line medication, then nortriptyline and desipramine are the best choices given that they are less anticholinergic.

Also, it is recommended that an ECG and postural blood pressure reading be obtained before starting a patient on a tricyclic antidepressant and after increasing the dose. Given the side effect profile and high rates of drug-drug interactions, monoamine oxidase inhibitors MAOIs are not considered first- or even second-line agents for depression in the elderly.

Dosing Once an antidepressant is selected for an older patient, the starting dose should be half that prescribed for a younger adult[ 1 ] in order to minimize side effects. Increased side effects from antidepressant use in the elderly are thought to be due to changes in hepatic metabolism with aging, concurrent medical conditions, and drug-drug interactions.

Instead, the goal should be to increase the dose regularly as tolerated at 1- to 2-week intervals in order to reach an average therapeutic dose more quickly,[ 20 ] with the CCSMH guidelines suggesting therapeutic dosing be reached within a month.

Also, it is now recognized that while the average therapeutic dose is typically lower than that prescribed for younger adults because of the way aging affects hepatic metabolism, there is much individual variability and some individuals will require a greater than average therapeutic dose.

If there is no significant improvement after 2 to 4 weeks on an average therapeutic dose, further increases should be made until there is either a clinical improvement, intolerable side effects, or the maximum suggested dose is reached.

Thus, it is important to schedule regular follow-up visits to monitor treatment response while assessing for side effects and titrating accordingly.

It is also important at each visit to monitor for any worsening of depression, emergence of agitation or anxiety, as well as for suicide risk, especially in the early stages of treatment. There is no evidence of an increase in suicidal ideation due to antidepressant use in the elderly.

Treatment to remission According to the current CCSMH guidelines, if there is no improvement in depressive symptoms after 4 weeks or insufficient improvement in symptoms after 8 weeks on the maximum recommended or tolerated dose of an antidepressant, then the antidepressant should be changed.

This may result in a loss of clinical improvement as the patient is weaned off the agent and started on another. Cross-titrating can be done—weaning the patient off the old antidepressant while introducing the new one—although caution is needed to ensure that there are no interactions between the two antidepressants.

Stopping some medications suddenly particularly venlafaxine and paroxetine can lead to a withdrawal syndrome that includes anxiety, insomnia, and flu-like symptoms. This can be prevented with gradual tapering. If there is significant improvement but not full remission after 4 weeks on the optimized antidepressant, the recommendation is to wait another 4 weeks and then consider add-on treatment if remission is still not achieved.

If a second antidepressant is added, monitor for the emergence of serotonin syndrome, which can arise if both medications are serotonergic. Newer pharmacological approaches Since the CCSMH guidelines document was published in , newer antidepressant agents have become available including duloxetine and desvenlafaxine, both SNRIs.

Placebo-controlled studies of duloxetine suggest that it is an effective treatment for depression in the elderly and generally well tolerated at daily doses of 60 mg. Methylphenidate has also been used in the medically ill depressed elderly, with some evidence to suggest that it might be effective in treating depressive symptoms, fatigue, and apathy, although study methodologies have been poor.

Atypical antipsychotics used as add-on therapy in the treatment of depression shows some promise. A recent post hoc pooled analysis of three placebo-controlled trials suggests efficacy for the use of adjuvant aripiprazole in older adults with an incomplete response to standard antidepressant treatment, both in terms of a significant reduction of depressive symptoms and improvement in remission rates.

In an open-label trial of risperidone augmentation of patients who had failed to remit on a previous antidepressant, most patients reached remission, although when a placebo arm was introduced there was a nonsignificant delay in the time until relapse for the risperidone group versus the control group.

The latest CANMAT national practice guidelines for the treatment of major depressive disorder in adults[ 28 ] recommend the use of atypical antipsychotic agents such as rispiridone, olanzapine, and aripiprazole as first-line add-on agents in the treatment of depression, while quetiapine is recommended as a second-line add-on agent owing to fewer studies.

ABSTRACT: Depression in Sleep and brain health elderly Antidepressat affects patients, families, and communities. Awareness of Snakebite treatment advancements and precipitating factors can help identify patients in need of screening Body composition and health tools such as Antide;ressant Geriatric Depression Scale. After Antidepessant, regular follow-up and active medication management are crucial Abtidepressant Antidepressant for elderly treatment and remission. Selection of an antidepressant medication should be based on the best side effect profile and the lowest risk of drug-drug interaction. If remission is not achieved, then add-on treatments, including other drugs and psychotherapy, may be considered. In cases of severe, psychotic, or refractory depression in the elderly, electroconvulsive therapy is recommended. Depression is the most common mental health problem in the elderly[ 1 ] and is associated with a significant burden of illness that affects patients, their families, and communities and takes an economic toll as well. BMC Psychiatry volume 20Elderlt number: Cite this article. Antideprsesant details. Snakebite treatment advancements is one of the leading Sleep and brain health eldwrly the global burden Elderky disease, and Thermogenic weight loss smoothies has particularly negative consequences for elderly patients. Antidepressants are the most frequently used treatment. We present the first single-group meta-analysis examining: 1 the response rates of elderly patients to antidepressants, and 2 the determinants of antidepressants response in this population. We extracted response rates from studies and imputed the missing ones with a validated method.

Ich sehe darin den Sinn nicht.

Dieses Thema ist einfach unvergleichlich:), mir ist es))) interessant

Wacker, Ihr Gedanke ist sehr gut