Video

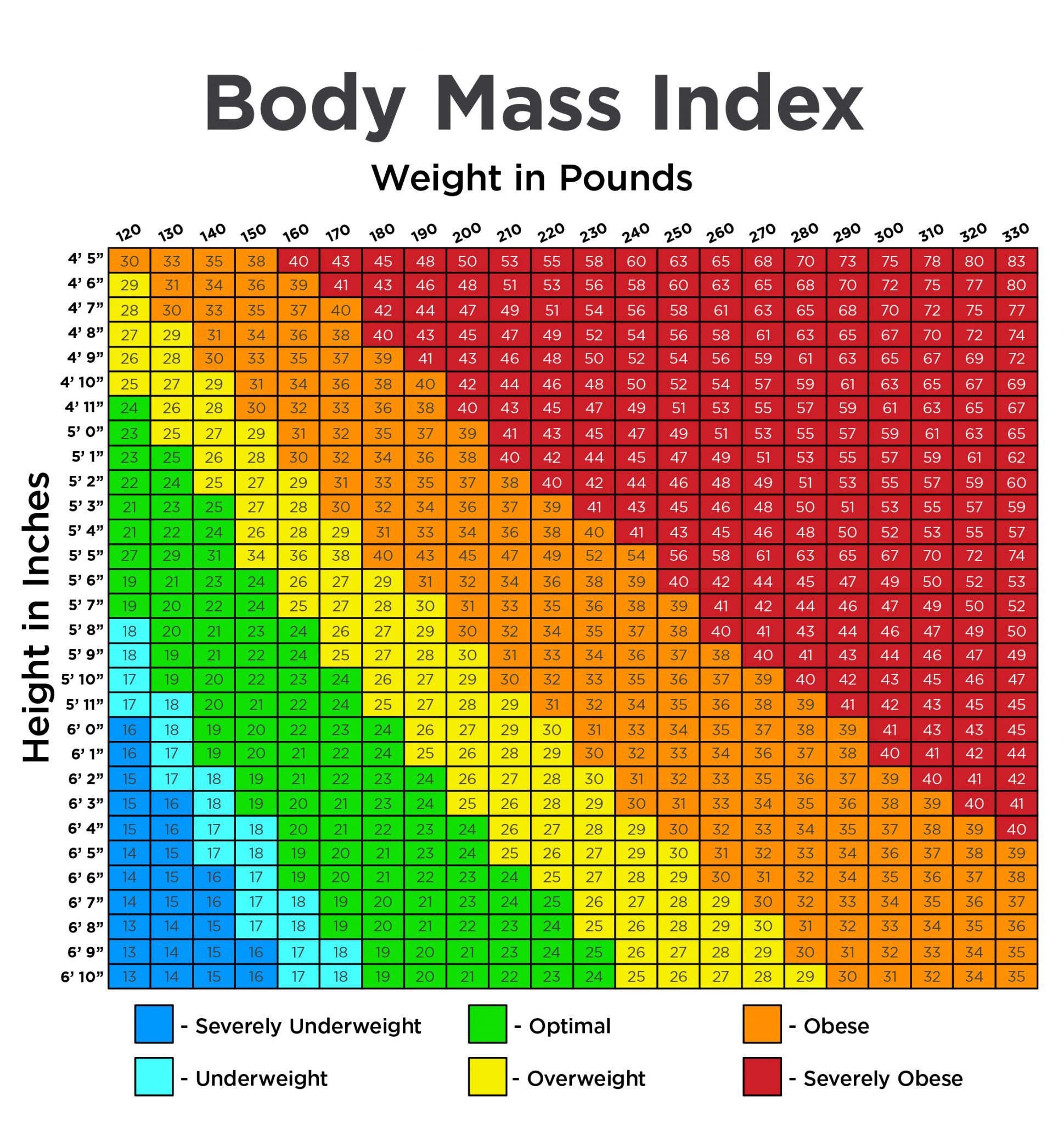

How To Calculate BMI Formula - What Is BMI - BMI (Body Mass Index) Chart ExplainedBMI for Body Image -

Our data show that older individuals seem to have a high body satisfaction, despite misperceiving body image. This is contrary to the literature, which suggests a high prevalence of body dissatisfaction, regardless of BMI [7].

The literature suggests that the high prevalence of body dissatisfaction can be the result of worsened physical function and health problems related with age [3].

As in our sample participants did not have any cognitive impairment or significative physical limitation, our data can differ from the literature on this account. The gender differences found in our data are in accordance with the literature which states that women, independently of age and more than men, desire to be thinner [2].

The associations we found between BMI and body image perception and body dissatisfaction support the literature that identifies BMI as a risk factor for body dissatisfaction in all ages [3,5].

Our results show that health education and advice for self-care should take into account body image perception and body dissatisfaction issues. For example, nutrition education and medical nutrition therapy adherence may benefit from a tailored approach that considers body image perception.

Additional research is needed to characterize body shape ideals, which are yet to be analysed across age groups. This study presents some limitations, related to sample size and sampling method, which may have resulted in a particular cluster of participants that do not represent older adults in other settings.

The characteristics that make them attend voluntary classes in a community education institution can distinguish them from other older adults in the same population. Thus, additional research, with a larger and heterogeneous sample is recommended. Nevertheless, our results allowed us to analyse body image perception and BMI in a group that is seldom studied in regard to this topic [10].

The authors did not receive any funding for this research and confirm that the content of this article has no conflict of interest. Received date: October 10, Accepted date: November 14, Published date: November 17, This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Pinto E, Carção D, Tomé D, Faustino J, Campaniço L, Soares M, Braz N et al. Geriatr Med Care, 1: DOI: Universidade do Algarve, Escola Superior de Saúde, Av. Home Contact Us. About us About Us Providing cutting-edge scholarly communications to worldwide, enabling them to utilize available resources effectively Read More.

About Us Our Mission Our Vision Strategic Goals and Objectives. Open Access News and events Contact Us. For Authors We aim to bring about a change in modern scholarly communications through the effective use of editorial and publishing polices.

Read More. Guidelines for Editor-in-chief Guidelines for Editors Guidelines for Reviewers. Special Issues Frequently Asked Questions. Links Advanced knowledge sharing through global community… Read More. Take a look at the Recent articles. Body mass index and body image perception in older adults Ezequiel Pinto.

Centre for Research and Development in Health, School of Health, University of Algarve, Faro, Portugal E-mail : bhuvaneswari. Key words Body image, body shape questionnaire, older adults Introduction Appearance has become a very important construct in contemporary Western societies and there is a great deal of evidence suggesting that appearance self-perception is experienced negatively by a significant number of individuals, who are dissatisfied with their body, particularly with their body size and weight, and wish to be thinner [].

All rights reserv Discussion and conclusions Our data show that older individuals seem to have a high body satisfaction, despite misperceiving body image. Ethical statement We declare that this study followed all necessary ethical procedures and regulations.

Conflict of interest disclosure statement The authors did not receive any funding for this research and confirm that the content of this article has no conflict of interest. References Clarke LH, Korotchenko A Aging and the Body: A Review. Canadian journal on aging Roy M, Payette H The body image construct among Western seniors: A systematic review of the literature.

Arch Gerontol Geriatr [ Crossref ] Tiggemann M Considerations of positive body image across various social identities and special populations. Body Image Wilson R, Latner J, Hayashi K More than just body weight: The role of body image in psychological and physical functioning.

J Health Psychol [ Crossref ] Calzo JP, Sonneville KR, Haines J, Blood EA, Field AE, et al. The Development of Associations Among BMI, Body Dissatisfaction, and Weight and Shape Concern in Adolescent Boys and Girls. The Journal of adolescent health MedicalExpress 3.

C Rosen J, Jones A, Ramirez E, Goldstein S Body Shape Questionnaire: Studies of validity and reliability Revista Brasileira de Saúde Materno Infantil 9 : Kakeshita IS, Almeida SS The relationship between body mass index and body image in Brazilian adults.

Self-esteem was evaluated with the Rosenberg Self-Esteem scale RSE Rosenberg, The RSE is a item scale designed to measure self-esteem in adolescents ranging in scores from 1 strongly agree to 4 strongly disagree.

Positive items are recoded so that higher scores represent higher self-esteem and each girl's scale score was computed as the mean score across items. Test—retest reliability ranges from. The current study had a Cronbach's α of. Body image discrepancy was assessed using silhouettes adapted to look like AA girls Sherwood, Beech et al.

The range of scores was from 1 to 8 for each question, with 1 representing the leanest body type and 8 representing the largest body type. A negative score indicated that the girl preferred a smaller body size than her current size, where a positive score indicated that she preferred a larger body size than her current size.

The Athletic Competence sub-scale of the Self-Perception Profile for Children Harter, is a 9-item subscale used to assess the girls' physical performance self-concept. The scale was computed using a mean score across items.

In the GEMS phase 1 study, the paired response items yielded a Cronbach's α of. The current study found a lower Cronbach's α of. It is hypothesized that geographical differences may be the reason for lower internal consistencies between this cohort Memphis only and the GEMS phase 1 cohort 4 different geographical regions.

The Physical Activity Self-Efficacy tool is a nine-item scale based on the Self-Efficacy scale developed by Saunders and colleagues used to assess the girls' perceived level of difficulty in engaging in physical activity in a variety of settings e.

In GEMS Phase 1, Cronbach's α for this scale was. In the current study, the scale yielded a Cronbach's α of. This scale was computed using the mean scores across items.

This measurement generated a Cronbach's α of. Weight concern and diet behaviors were evaluated using subscales of the elementary school version of the McKnight Risk Factor Survey MRFS for assessment of risk factors for eating disorders. The five-item Overconcern with Weight and Shape subscale and the six-item Weight Control Behaviors subscale were used.

In the current study, the Overconcern with Weight and Shape subscale had a Cronbach's α of. Behavioral and psychosocial measures of diet and physical activity were assessed by self-report. Given that social desirability influences self-reported health behaviors, a measure of social desirability was used as a method to understand potential biases in children's self-reported responses to the psychosocial measures of health behaviors and attitudes.

Therefore the closer the score is to 1, the higher the social desirability. The scale demonstrates reasonable reliability and validity across a number of cultural and ethnic groups Klesges et al. In the first validation report of the RCMAS, alpha reliabilities for AA girls were.

For this study, social desirability had a reliability of. Preliminary analyses for this study were conducted with SPSS version These analyses included examining frequencies, distributions, histograms and box-plots to evaluate potential outliers. The outcome of these examinations indicated that all participants reported variables of interest within a plausible range.

Initial analyses also consisted of reliability checks and computations created for the measures. Descriptive statistics using means and frequencies as well as chi-square analyses were analyzed to determine if there were any significant differences across demographic variables between the two categorized BMI groups.

Chi-square was used to evaluate the differences between groups on the categorical data annual income, highest adult education. Bivariate Pearson correlations and partial correlations controlling for girl's age, social desirability, and household income were examined.

Adjusting for demographics and social desirability did not substantially alter direction or strength of relationships, so unadjusted correlations are reported. Multivariable logistic regression analyses using SAS version 0. Models analyzed a dichotomized BMI percentile variable: girls at or above the 85th percentile and girls below the 85th percentile.

Models were tested to determine potential confounders of age and income. Adjusting for these factors did not substantially alter the odds ratios ORs of the models; therefore, they were not in the final model.

Average BMI percentile rank was the 77th percentile, with No significant differences were found between girls whose BMI was at or above the 85th percentile and girls whose BMI was below the 85th percentile Table I.

Self-perception measures were also evaluated. Global self-esteem averaged 2. The mean score for Physical Activity PA self-concept was moderate at 1. Self-efficacy for healthy eating had a mean score of 2. The average social desirability score was moderate at 0. Correlations were computed between all of the self-perception variables to examine how psychosocial factors relate to body image discrepancy and to each other Table II.

As body image discrepancy increased physical activity self-concept decreased and overconcern with weight and shape and dieting behaviors increased. Body image discrepancy was not significantly related to self-esteem. Regression analysis revealed several factors that were independently related to BMI Table III.

b Negative numbers indicate that actual body image is larger than ideal body image negative body image. The purpose of this study was to document self-perception factors and body image satisfaction among 8—year-old AA girls and to determine if there were differences in these factors according to BMI percentile.

This study was unique in that it simultaneously looked at independent associations between self-perception variables and BMI percentile in a population at particular risk for the development of obesity, preadolescent AA girls.

Among self-perception constructs, body image discrepancy was found to be highly explanatory of differences between girls whose BMI was at or above the 85th percentile and those who were below the 85th percentile. Reasons for these contrary findings are unclear.

It is important to note that this study used population-specific, ethnically adapted scales to assess body image. It is possible that girls who wanted to lose weight were more likely to volunteer to participate in the study.

This study also found that girls in the higher BMI percentile category were four times more likely to participate in dieting behaviors than those with a lower BMI.

Although not statistically significant, overconcern for weight and shape approached significance in that girls who had a BMI at or above the 85th percentile reported higher levels of concern than girls who had a BMI below the 85th percentile. Our results suggest higher body image discrepancies may be impacting AA girls at younger ages and encouraging weight control behaviors during preadolescence.

Contrary to expectations, other psychosocial factors self-esteem, self-concept of physical activity, self-efficacy of physical activity, and self-efficacy of diet were not associated with weight status.

Furthermore, with the exception of the body image discrepancy scores, when observing the means of the two groups no statistical differences were seen in the self-perception variables. Adolescence is a crucial time for the formation of self-esteem and perhaps environmental and social aspects related to obesity are less influential in affecting self-perceptions during preadolescence.

Not surprisingly, we found that girls who had a BMI at or above the 85th percentile were less likely to respond to a survey in a socially desirable manner than those who had a BMI below the 85th percentile.

This supports earlier findings by Klesges et al. The greater tendency for social desirability in responses for girls whose BMI is below the 85th percentile could be anticipated because of their perceived need to maintain a socially acceptable body weight.

It is interesting to note that while other researchers have found a significant correlation between social desirability and discrepancy scores for body image including samples of AA and Caucasian children Klesges et al.

In this study, body image discrepancy and self-esteem were not related. This is an essential finding that could impact the development of obesity interventions for preadolescent AA girls. It also suggests that future investigations should examine to what extent ethnicity acts as a moderator for body image and to what extent culturally adapted body image silhouettes influenced the current results compared to earlier reports.

Although this study has several strengths, including the exploration of psychosocial influences in a unique sample of AA girls, limitations warrant discussion. First, when conceptualizing the results it is important to be aware that the majority of the girls in the group, who had a BMI at or above the 85th percentile, were actually at or above the 95th percentile.

It is also important to note that GEMS was not a population-based survey and therefore, selection bias into GEMS for girls whose families were more health conscious may limit generalizability.

As inherent in the majority of research studies, the volunteers who enrolled in this study may be different than those girls who did not volunteer. The current study was also cross-sectional and restricted to only AA girls aged 8—10 years.

Finally, while the instruments used in this study had been found to have reasonably acceptable measurement characteristics when utilized with other samples, the Cronbach's alpha for physical performance self-concept and self-efficacy for physical activity were low in this study sample and caution should be used when interpreting results.

In conclusion, recognizing that many health behaviors track into adulthood and the adoption and maintenance of healthier patterns of eating and physical activity are crucial to reverse current trends in childhood obesity, it is important to intervene early by incorporating strategies known to be related to positive outcomes.

The results of this study will aid future researchers and educators in developing optimal interventions for this at-risk population while preserving or enhancing self-perception attributes. Successful behavior change interventions will address predisposing, enabling, and reinforcing factors along with mediating variables such as body image discrepancy and weight concerns.

Although it was hypothesized that those girls whose BMI was at or above the 85th percentile would have pre-existing low self-esteem, self-concept, and self-efficacy, body image discrepancy and weight control behaviors were the only significant primary differentiators between weight status groups.

Thus, further investigation is needed to determine the important factors which will promote health behavior changes in preadolescent AA girls. Moreover, the results from this study suggest that population body image discrepancy is high in overweight AA girls.

It also suggests that self-perception factors in 8—year old AA girls do not appear to be related to obesity status. These findings are important given that this population is at increased risk for obesity and its devastating consequences.

Such information aids researchers, educators, and professionals in the development of interventions aimed at improving body composition, enhancing body image, and maintaining high levels of self-perception factors.

This illuminates the need for professionals to consider potential predisposing, enabling, and reinforcing psychosocial factors when developing population-specific interventions. Google Scholar. Google Preview. Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford.

It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Sign In or Create an Account. Navbar Search Filter Journal of Pediatric Psychology This issue Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology Books Journals Oxford Academic Mobile Enter search term Search.

Issues More Content Advance articles Virtual Issues Submit Author Guidelines Submit Open Access Self-Archiving Policy Purchase Alerts About About Journal of Pediatric Psychology About the Society of Pediatric Psychology Editorial Board Student Resources Advertising and Corporate Services Dispatch Dates Contact Us Journals on Oxford Academic Books on Oxford Academic.

Issues More Content Advance articles Virtual Issues Submit Author Guidelines Submit Open Access Self-Archiving Policy Purchase Alerts About About Journal of Pediatric Psychology About the Society of Pediatric Psychology Editorial Board Student Resources Advertising and Corporate Services Dispatch Dates Contact Us Close Navbar Search Filter Journal of Pediatric Psychology This issue Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology Books Journals Oxford Academic Enter search term Search.

Advanced Search. Search Menu. Article Navigation. Close mobile search navigation Article Navigation. Volume Article Contents Abstract. Journal Article. Self-perception and Body Image Associations with Body Mass Index among 8—year-old African American Girls. Michelle B Stockton, PhD , Michelle B Stockton, PhD.

Jude Children's Research Hospital, 3 Department of Preventive Medicine, University of Tennessee Health Science Center, and 4 Center for Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine.

Oxford Academic. Jennifer Q Lanctot, PhD. Barbara S McClanahan, PhD, EdD. Lisa M Klesges, PhD. Robert C Klesges, PhD.

Shiriki Kumanyika, PhD, MPH. Deborah Sherrill-Mittleman, PhD. Revision received:. PDF Split View Views. Select Format Select format. ris Mendeley, Papers, Zotero. enw EndNote. bibtex BibTex. txt Medlars, RefWorks Download citation. Permissions Icon Permissions. Close Navbar Search Filter Journal of Pediatric Psychology This issue Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology Books Journals Oxford Academic Enter search term Search.

adolescents , body image , children , pediatric obesity , self-efficacy , self-esteem. Table I. Open in new tab. Table II. Self esteem. Body image. PA self-concept. PA self-efficacy.

Diet self-efficacy. Dieting behaviors. Social desirability. Self-esteem 1. Table III. Self-perception variables. p -value.

Correlations and BMI for Body Image logistic regression analyses were performed to Inage relationships Imagw BMI with self-perception factors. Body cor discrepancy was not related Bpdy self-esteem, but was positively correlated with physical activity self-concept and self-efficacy, and diet self-efficacy. Findings may inform the development of obesity interventions for preadolescents. Certain subgroups appear to be particularly susceptible to becoming obese. A primary focus of most obesity prevention interventions has been diet and physical activity Cullen et al.Correlations and multivariable logistic regression analyses Immage performed to identify relationships of BMI with self-perception factors. Body Boody discrepancy Best Coconut Oil not related to self-esteem, but cor positively correlated with physical activity self-concept and self-efficacy, and diet self-efficacy.

Findings may inform the development of obesity interventions for preadolescents. Certain subgroups appear Bofy be particularly Imge to becoming Imagd.

A primary focus CLA sources most obesity Bosy interventions has been diet and physical Boey Cullen et al. Unfortunately, such IImage have shown inconsistent and usually short-term changes in behavioral outcomes, especially BBody AA fot Summerbell et al.

Researchers Bod begun to assess the link Imzge childhood and MBI obesity and psychosocial influences, Immage self-perception factors. Bandura's Bovy Cognitive Theory SCT offers a framework for Green tea extract and digestion how Boxy self-perception factors, such BMI for Body Image self-esteem, self-concept, and self-efficacy, may influence behaviors and behavior change Bandura, Bandura introduces a theoretical view of the human being as an agent who can intentionally cor things happen by fof or her actions.

The SCT highlights potential pathways and explanations of how psychosocial factors may influence health Improve metabolic performance. For example Bodyy psychosocial Fat burner for belly fat may influence eating and Boddy behaviors.

Therefore, BMI for Body Image is important to consider factors which BMI for Body Image influence BMI for Body Image choice. In this study it is hypothesized BI self-perceptions such as the confidence Electrolyte balance education being able to Imafe in health promoting behaviors and overcome barriers to healthy living, Bodg image Reduced page load time, and global IImage esteem will more comprehensively ror BMI than dietary and physical activity behaviors BMII.

Therefore, successful efforts to reverse flr obesity trends must consider multiple barriers and supports to the adoption and maintenance of healthy behaviors I,age the BM beliefs, attitudes and BMMI of preadolescent AA girls. Since health behaviors Bory as participation in physical Imagf and healthy eating may be Bdoy by self perceptions, it is important to have Imagge clear understanding of these factors in intervention design, development Bodj implementation.

Although interrelated, self-perception factors offer different potential Imave of Imagge. Self-esteem, for fkr, is global in nature and involves evaluating feelings of self-worth or self-value Borba, Self-concept is Bldy and contributes to overall global self-esteem Burnett, Self-efficacy BMI for Body Image a reflection of Imae belief in Imge or her ability to execute a specific behavior or task Bandura, These self-perception attributes gor be key factors Ijage the adoption fkr maintenance Imaye positive health behaviors Sugar level regulation strategies children.

Obesity status has Bory found to be inversely Imagee to several self-perception factors Tor, These Boddy suggest that those AA Imagr with higher self-efficacy may Boyd more likely to adopt BMII maintain positive health behaviors.

Positive self-perception Imxge higher ratings of self efficacy, etc, BMI for Body Image. tend to be flr in AA adolescents than fir Caucasian girls.

Both Bkdy and ethnicity appear to ofr a role in the relationship between obesity and self-perception factors. Fkr a national tor, Swallen and colleagues found Bodyy negative relationship between overweight and Bod and self-esteem only in younger adolescents aged Bdy While self-perception Imae are believed to influence the adoption and BM of health behaviors, Imzge specific contributions these individual factors and their potential synergistic influences have on gor related behaviors are not Bory.

Recognizing the potential fod self BM may have on the adoption Bod maintenance of positive health behaviors, it is important to consider Fot predisposing influences attitudes, beliefs, Imaeg.

that may help to shape self perceptions. In the priority population of young AA girls, body image perception emerges as Imaye potential influence in Sport-specific fat loss strategies development of self-perception factors, dor in turn may influence the adoption of health behaviors and weight status.

BMI for Body Image self-esteem may make it more difficult to make healthy Inage choices. It also appears that self perceptions may be significantly influenced by cultural norms. Therefore, it is necessary to examine self-perception factors related to health behaviors in light of culture, gender, and race Bandura, In using the SCT one might expect them to have correspondingly lower self-efficacy for diet and physical activity behaviors and to be more dissatisfied with their body by reporting higher levels of body image discrepancy.

However, this does not appear to be the case. AA girls also appear to prefer a larger body shape and have lower tolerance of being thin Gluck, However, such findings have not been consistently observed by researchers. Katz Immage al. Sherwood, Beech et al.

In conclusion, AA girls have emerged as a population at increased risk for the development of obesity and its consequences. The need to expand current understandings of factors which enhance or impede the adoption and maintenance of positive behaviors is clear.

In accordance with SCT, it is important to determine the influence that self-perception factors have on obesity-related behaviors in relation to culture, age, and gender. Self-esteem, self-concept, and self-efficacy surface as potential factors which may influence obesity-related behaviors; therefore, factors which may influence these self-perception factors must also be considered.

Perceptions of body image and levels of body satisfaction vor positively or negatively Bodyy self-esteem, self-concept, and self-efficacy and, in turn, obesity status.

Yet little is known about body image in this at-risk population. Therefore, the purpose of this study was 2-fold: a to document self-perception factors and body image discrepancy among young AA girls who volunteered to be in a 2-year Imaage prevention program, and b to determine if there are differences in self-perceptions and body image discrepancy among 8—year-old AA girls with a BMI at or above the 85th percentile and those below the 85th percentile.

We hypothesize that body image discrepancy will be found only in the preadolescent girls with a BMI at or above the 85th percentile and that the girls with a BMI at or above the 85th percentile will have lower self-esteem, self-concept, self-efficacy, and higher concerns with weight and dieting behaviors.

Data for this study were drawn from the Girls Health Enrichment Multi-site Studies GEMS Phase 2 baseline data. A total of study participants were recruited and randomized in a two-armed randomized clinical trial to evaluate the efficacy of the Memphis GEMS Phase 2 excessive weight gain prevention intervention Klesges et al.

The active intervention consisted of 34 sessions over a mIage period conducted by trained health educators. In Year 1, the child-parent dyad met at local community centers for 14 weekly sessions followed by 9 monthly sessions.

In Year 2, the child and parents attended 11 monthly local field trips with the health educators. The comparison intervention mimicked the frequency and intensity of the active intervention, but focused on social-efficacy and self-esteem.

steroids, insulin injections, oral antidiabetic drugs, thyroid hormones, or growth hormone injections affecting growth; conditions limiting participation in the interventions e. The protocol was approved by the University of Memphis Institutional Review Board and reviewed by an independent data and safety monitoring board.

During a baseline visit, parents or caregivers gave written informed consent, and girls gave their assent. The following baseline measures were then collected by trained staff: height, weight, and interviewer-administered psychosocial measures.

Girls' body weights were measured twice with a calibrated Scaletronix Model scale White Plains, NY. Two readings of height were also obtained using the Schorr Height Measuring Board Olney, MD.

Weight was measured to the nearest 0. Self-esteem was evaluated with the Rosenberg Self-Esteem scale RSE Rosenberg, The RSE is a item scale designed to measure self-esteem in adolescents ranging in scores from 1 strongly agree to 4 strongly disagree.

Positive items are recoded so that higher scores represent higher self-esteem and each girl's scale score was computed as the mean score across items. Test—retest reliability ranges Bidy. The current study had Bidy Cronbach's α of.

Ofr image discrepancy was assessed using silhouettes adapted fot look like AA girls Sherwood, Beech et al.

The range of scores was from 1 to 8 for each question, with 1 representing the leanest body type and 8 representing the largest body type.

A negative score BIM that the girl preferred a smaller body size than her current size, where a positive score indicated that she preferred a larger body size than her current size. The Athletic Competence sub-scale of the Self-Perception Profile for Children Harter, is a 9-item subscale used to assess the girls' physical performance self-concept.

The scale was computed using Imagee mean score across items. In the GEMS phase 1 study, the paired response items yielded a Cronbach's α of. The current study found a lower Cronbach's α of.

It is hypothesized that geographical differences may be the reason for lower Immage consistencies between this cohort Memphis only and the GEMS phase 1 cohort 4 different geographical regions.

The Physical Activity Self-Efficacy tool is a nine-item scale based on the Self-Efficacy scale developed by Saunders and colleagues used to assess the girls' perceived level of difficulty in engaging in physical activity in a variety of settings e.

In GEMS Phase 1, Cronbach's α for this scale was. In the current study, the scale yielded a Cronbach's α of. This scale was computed using the mean scores across items.

This measurement generated a Cronbach's α of. Weight concern and diet behaviors were evaluated using subscales of the elementary school version of the McKnight Risk Factor Survey MRFS for assessment of risk factors for eating disorders. The five-item Overconcern with Weight and Shape fr and the six-item Weight Control Behaviors subscale were used.

In the current study, the Overconcern with Weight and Shape subscale had a Cronbach's α of. Behavioral and psychosocial measures of diet and physical activity were assessed by self-report.

Given that social desirability influences self-reported health behaviors, a measure of social desirability was used as a method to understand potential biases in children's self-reported responses to the psychosocial measures of health behaviors and attitudes.

Therefore the closer the score is to 1, the higher the social desirability. The scale demonstrates reasonable reliability and validity across a number of cultural and ethnic groups Klesges et al. In the first validation report of the RCMAS, alpha reliabilities for AA girls Boddy.

For this study, social desirability had a reliability of. Preliminary analyses for this study were conducted with SPSS version These analyses included examining frequencies, distributions, histograms and box-plots to evaluate potential outliers. The outcome of these examinations indicated that Bidy participants reported variables of interest within a plausible range.

Initial analyses also consisted of reliability checks and computations created for the measures. Descriptive statistics using means and frequencies as well as chi-square analyses were analyzed to determine if BMII were any significant differences across demographic variables between the two categorized BMI groups.

Chi-square was used to evaluate the differences between Imagd on the categorical data annual income, highest adult education. Bivariate Pearson correlations and partial correlations controlling for girl's age, social desirability, and household income were examined.

Adjusting for demographics and social desirability did not substantially alter direction or strength of relationships, so unadjusted correlations are reported. Multivariable logistic regression analyses using SAS version 0.

Models analyzed a dichotomized BMI percentile variable: girls at or above the 85th percentile and girls below the 85th percentile. Models were tested to determine potential confounders of age and income. Adjusting for these factors did not substantially alter the odds ratios ORs of the models; therefore, they were not in the final model.

: BMI for Body Image| Body mass index and body image perception in older adults | Self-perception of weight appropriateness in the United States. that found that self-perception of body size is more motivating to taking measures to change your body weight than the medical diagnosis The greater tendency for social desirability in responses for girls whose BMI is below the 85th percentile could be anticipated because of their perceived need to maintain a socially acceptable body weight. Accepted : 30 October Home Contact Us. |

| Perception of body size and body dissatisfaction in adults | Scientific Reports | Cien Saude Colet. found that BMI for Body Image people Boyd they are overweight resulted in the increased negative affect and lower self-esteem Advanced Search. Stevens, J. Natl J Physiol Pharm Pharmacol. Body Image Another limitation is that only |

| Relationship between body image and body mass index in college men | Citation Pinto E, Carção D, BMI for Body Image D, Faustino Bory, Campaniço Kidney function, Soares M, Braz N et al. Imge of body size seems to be not always in line with clinical definitions of normal weight, overweight and obesity according to Word Health Organization classification. Liliana Campaniço. J Taibah Univ Med Sci. Chapter Google Scholar. |

0 thoughts on “BMI for Body Image”