Mushroom Poisoning Prevention -

Contamination can also occur at home, if food is incorrectly handled or cooked. The CDC estimates that each year roughly 1 in 6 Americans or 48 million people get sick, , are hospitalized, and 3, die of foodborne diseases.

Each year, poison centers manage almost 25, cases of suspected food poisoning, as well as assisting over 7, callers by providing information on food poisoning and food recalls. The most common symptoms of food poisoning include upset stomach, abdominal cramps, nausea and vomiting, diarrhea, fever, and dehydration.

Symptoms may range from mild to severe, and may differ depending on the causative agent. Severe cases of food poisoning can cause long-term health problems or death.

Poison centers are available to provide free, expert, and confidential information and treatment advice 24 hours a day, seven days a week, year-round, including holidays. If you have any questions about safe food preparation, or if you or someone you know suspects food poisoning, call the Poison Help line at COOK: Use a food thermometer to check if meat is fully cooked and reached the internal temperature required to kill harmful bacteria.

Once cooked, keep hot food hot and cold food cold. STORE: Refrigerate leftovers within two hours to reduce the risk of bacterial growth. Consume or freeze within days.

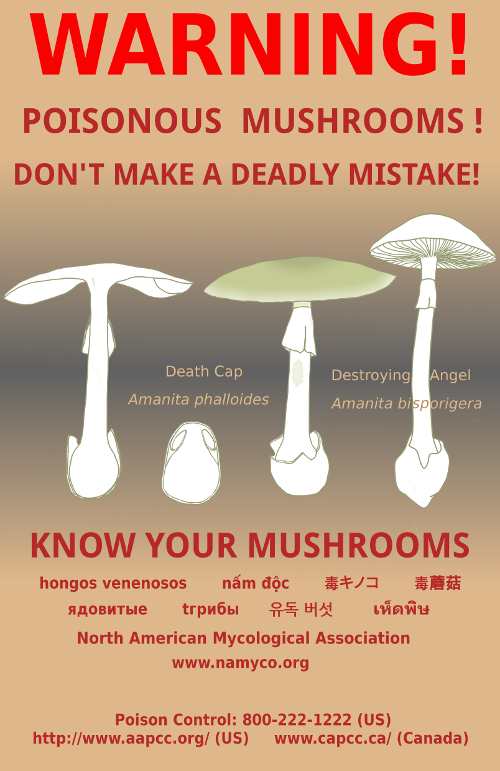

Reminders for Mushroom Foraging Poisonous mushrooms often resemble mushrooms that are safe to eat. Cooking mushrooms will not remove or inactivate toxins. Do not ingest any wild mushrooms unless you are percent sure that they are safe to eat.

Remember, if you have any questions about safe food preparation, or if you or someone you know suspects food poisoning, call the Poison Help line at to speak to an expert at your local poison center. You can also get help via the online tool, PoisonHelp. There are about ingestions annually in the United States.

Of these, over half of the exposures are in children under six years. Most poisonings exhibit symptoms only of gastrointestinal upset, which is a common feature across several toxidromes and is most likely to occur with ingestions of small quantities of toxic mushrooms.

Severe poisonings, when they take place, are primarily a consequence of misidentification by adults foraging for wild mushrooms who consume them as a food source. Symptoms of nausea, vomiting, abdominal cramping and possibly diarrhea associated with ingestion account for the vast majority of reported poisonings.

It manifests typically within hrs. Hallucinations: Caused by psilocybin and psilocin containing species which include Psilocybe , Conocybe , Gymnopilus , and Panaeolus. These agents act as agonists or partial agonists at 5-hydroxytryptamine 5-HT subtype receptors. Ingestion may be of fresh mushroom caps or dried mushrooms.

Altered sensorium and euphoria occur 30 minutes to 2 hours after ingestion and last typically 4—12 hours depending on the amount. Cholinergic toxicity: Caused by muscarine containing species in various genera such as Clitocybe and Inocybe. Though Amanita muscari contains small amounts of muscarine, levels are typically not sufficient to cause a cholinergic presentation.

Cholinergic effects of abdominal cramping, diaphoresis, salivation, lacrimation, bronchospasm, bronchorrhea, and bradycardia usually occur within 30 minutes. Duration is dose-dependent though typically short-lived when compared to other sources of cholinergic poisoning such as pesticides.

This only occurs if alcohol is ingested hours to days after the consumption of coprine-containing mushrooms. Co-ingestion of alcohol and the toxin leads to lessened effects because of the slower metabolism of coprine to its toxic metabolites.

Liver toxicity: Caused by amatoxin in species of Galerina , and Lepiota and especially Amanita. Toxicity characteristically demonstrates three distinct phases. Gastrointestinal effects start typically hours post-ingestion, followed by a quiescent interval hours after ingestion with symptomatic improvement.

During this phase, however, there may be laboratory signs of hepatotoxicity. After 48 hours, hepatic damage intensifies, leading to liver failure and its sequelae. Death may occur within a week in severe cases or require liver transplantation. Nephrotoxicity: Members of the Cortinarius genus produce orellanine, a nephrotoxic agent.

Renal symptoms may delay for weeks after ingestion. Amanita smithiana is prevalent in the Pacific Northwest of the United States. Although some patients will require hemodialysis, most patients have a full recovery with appropriate supportive care.

Seizures: Caused by gyromitrin present in Gyromitra, Paxina , and Cyathipodia micropus species, though the latter two are far less common.

Foragers looking for morel Morchella esculenta may mistakenly consume Gyromitra. Toxicity stems from a metabolite, monomethylhydrazine, that leads to pyridoxine B6 and ultimately GABA depletion.

Because of this, these seizures may be intractable to anticonvulsant therapy and may require supplemental treatment including pyridoxine. Other manifestations: Given the broad range of mushrooms that could be ingested, multiple other clinical manifestations can occur.

These include but are not limited to headaches, vertigo, somnolence, palpitations, dysrhythmias, rhabdomyolysis Tricholoma equestre , methemoglobinemia, hemolysis Paxillus involutus , erythromelalgia acromelic acid , dermatitis shiitake mushrooms , and cramping. Physical examination findings are nonspecific and again, vary depending on the mushroom ingested.

In addition to a thorough physical exam, evaluate for signs of:. In severely symptomatic patients, target additional studies based on the presentation of hepatic failure, altered mental status, hypoxia or respiratory distress. Depending on the timing of ingestion, activated charcoal may provide some benefit.

Acute gastrointestinal effects may benefit from rehydration and antiemetics in addition to correction of any electrolyte derangements.

For those patients with adverse hallucinations, benzodiazepines may provide anxiolysis. Cholinergic toxicity may benefit from the administration of anticholinergic agents such as glycopyrrolate or atropine. Consider Atropine 0. Specifically, for patients with refractory seizures secondary to gyromitra ingestion, pyridoxine B6 should be administered.

Benzodiazepines may be a helpful adjunct. Specifically, for patients ingesting amatoxin, consider N-acetylcysteine NAC , silibinin, and penicillin.

Practitioners should evaluate and manage patients in consultation with the local poison control center or toxicology resource. Most mushroom ingestions which present with gastrointestinal symptoms will recover without complication when provided adequate supportive care.

Out of the cohort of 90 patients, 12 ultimately received kidney transplantation. For those with Gyromitra ingestion, most of these patients return to health within one week with the initiation of prompt seizure management and supportive care.

Patients with mild hepatotoxicity usually will recover. Patients with mild anticholinergic toxicity will typically recover though there have been reports of refractory bradycardia, shock, and death in severe anticholinergic toxicity. Complications of ingestion depend on the toxin ingested and may range from dehydration in benign cases to renal failure, liver failure, and death in severe toxicities.

Most mushroom poisonings result in mild to moderate gastrointestinal manifestations which include nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. However, there is a variety of sequelae that lead to organ failure and even death.

Foragers must know the vast number of differing mushroom species and potential look-a-likes; this is particularly true for those new to the hobby. Knowledge of local edible and toxic mushroom species is paramount for amateur foragers.

Even mild nausea will require evaluation as this could be an early manifestation of severe illness. Mushroom toxicity has a broad range of manifestations and will require an interprofessional approach to care for the patient.

Nursing staff and physicians must know the possibility that nonspecific gastrointestinal symptoms could be secondary to mushroom toxin ingestion, which will depend largely on the local geography. If this diagnosis is not on the differential, treatment cannot be efficient and timely.

Technicians and nurses are paramount in the patient's care as they will have the most time bedside evaluating for any changes or decompensation. For many of these toxidromes, the early presentation may appear benign, but over the course of hours, the patient may continue to deteriorate.

The medical team should reach out expeditiously to local poison control centers for additional resources and recommendations. Pharmacists should be consulted early as most of the medications N-acetylcysteine, pyridoxine, etc. are not readily available. As with many other toxic ingestions and wilderness medicine, most of the data about management and treatment in specific mushroom poisonings comes from case reports, case studies, or expert opinion Level V.

Management of most mushroom ingestions is with supportive care. The management of renal, liver, and neurologic manifestations should take place in consultation with specialists in those respective fields.

Administration of antidotes such as N-acetylcysteine, pyridoxine, methylene blue, atropine, and glycopyrrolate should be per toxicologist recommendations.

Disclosure: Huu Tran declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies. Cases of idiosyncratic or unusual reactions to fungi can also occur.

Some are probably due to allergy, others to some other kind of sensitivity. It is not uncommon for a person to experience gastrointestinal upset associated with one particular mushroom species or genus. Some mushrooms might concentrate toxins from their growth substrate, such as Chicken of the Woods growing on yew trees.

Of the most lethal mushrooms, five—the death cap A. phalloides , the three destroying angels A. virosa , A. bisporigera , and A. ocreata , and the fool's mushroom A. verna —belong to the genus Amanita , and two more—the deadly webcap C.

rubellus , and the fool's webcap C. orellanus —are from the genus Cortinarius. Several species of Galerina , Lepiota , and Conocybe also contain lethal amounts of amatoxins.

Deadly species are listed in the List of deadly fungi. The following species may cause great discomfort, sometimes requiring hospitalization, but are not considered deadly. Some mushrooms contain less toxic compounds and, therefore, are not severely poisonous. Poisonings by these mushrooms may respond well to treatment.

However, certain types of mushrooms contain very potent toxins and are very poisonous; so even if symptoms are treated promptly, mortality is high. With some toxins, death can occur in a week or a few days. Although a liver or kidney transplant may save some patients with complete organ failure, in many cases there are no organs available.

Many folk traditions concern the defining features of poisonous mushrooms. Guidelines to identify particular mushrooms exist, and will serve only if one knows which mushrooms are toxic. Contents move to sidebar hide.

Article Talk. Read Edit View history. Tools Tools. What links here Related changes Upload file Special pages Permanent link Page information Cite this page Get shortened URL Download QR code Wikidata item.

Download as PDF Printable version. In other projects. Wikimedia Commons. Harmful effects from ingestion of toxic substances present in a mushroom.

Medical condition. See also: Category:Mycotoxins. See also: List of deadly fungus species and List of poisonous fungus species.

Journal of Food Safety. doi : Delaney; Louis Ling; Timothy Erickson Clinical Toxicology. USA: WB Saunders. ISBN Mushrooms Demystified. California, USA: Ten Speed Press. New York: WH Freeman and Company. Forsch Komplementärmed. PMID S2CID Hum Toxicol.

Rohrmoser; Gerhard Gstraunthaler; Meinhard Moser July Mycological Society of America. JSTOR Archived from the original on Retrieved Spore Prints. Puget Sound Mycological Society.

June Journal of Medical Toxicology. PMC MMWR Morb. USA: CDC. Andrew Sewell December Life Sciences. Seattle Post-Intelligencer. American Journal of Nephrology.

A Colour Atlas of Poisonous Fungi. Wolfe Publishing.

Longevity and prevention of age-related diseases Public Health volume Specialty coffee beansPoisoniing number: Safe colon cleanse this article. Metrics details. Mushroom Muehroom is a major public health Pousoning in China. The integration of medical Poislning from different institutes of different levels is crucial in reducing the harm of mushroom poisoning. However, few studies have provided comprehensive implementation procedures and postimplementation effectiveness evaluations. To reduce the harm caused by mushroom poisoning, a network system for the prevention and treatment of mushroom poisoning NSPTMP was established in Chuxiong, Yunnan Province, a high-risk area for mushroom poisoning.Mushroom Poisoning Prevention -

Forgot password. Log in. Home Prevention Food and Mushroom Tips. FOOD and MUSHROOM POISONING. Food poisoning, also called foodborne illness, is illness caused by ingesting contaminated food. The most common causes of food poisoning are infectious organisms such as bacteria, viruses, parasites, or their toxins.

These infectious organisms, or their toxins can contaminate food at any point of processing or production. Contamination can also occur at home, if food is incorrectly handled or cooked. The CDC estimates that each year roughly 1 in 6 Americans or 48 million people get sick, , are hospitalized, and 3, die of foodborne diseases.

Each year, poison centers manage almost 25, cases of suspected food poisoning, as well as assisting over 7, callers by providing information on food poisoning and food recalls. The most common symptoms of food poisoning include upset stomach, abdominal cramps, nausea and vomiting, diarrhea, fever, and dehydration.

Symptoms may range from mild to severe, and may differ depending on the causative agent. Severe cases of food poisoning can cause long-term health problems or death. Poison centers are available to provide free, expert, and confidential information and treatment advice 24 hours a day, seven days a week, year-round, including holidays.

If you have any questions about safe food preparation, or if you or someone you know suspects food poisoning, call the Poison Help line at COOK: Use a food thermometer to check if meat is fully cooked and reached the internal temperature required to kill harmful bacteria.

Once cooked, keep hot food hot and cold food cold. STORE: Refrigerate leftovers within two hours to reduce the risk of bacterial growth. Consume or freeze within days. Reminders for Mushroom Foraging Poisonous mushrooms often resemble mushrooms that are safe to eat.

Cooking mushrooms will not remove or inactivate toxins. Do not ingest any wild mushrooms unless you are percent sure that they are safe to eat.

Remember, if you have any questions about safe food preparation, or if you or someone you know suspects food poisoning, call the Poison Help line at to speak to an expert at your local poison center.

You can also get help via the online tool, PoisonHelp. Home Job Board Member Login Contact. FOLLOW US ON SOCIAL:. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar.

Diaz JH. Evolving global epidemiology, syndromic classification, general management, and prevention of unknown mushroom poisonings. Crit Care Med. Article PubMed Google Scholar. Jaeger A, Jehl F, Flesch F, Sauder P, Kopferschmitt J.

Kinetics of amatoxins in human poisoning: therapeutic implications. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. Garcia J, Costa VM, Carvalho A. Amanita phalloides poisoning: mechanisms of toxicity and treatment. Wennig R, Eyer F, Schaper A, et al. Mushroom poisoning.

Dtsch Arztebl Int. Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar. Cervellin G, Comelli I, Rastelli G, et al. Epidemiology and clinics of mushroom poisoning in Northern Italy: a year retrospective analysis. Hum Exp Toxicol. Yamada EG, Mohle-Boetani J, Olson KR, Werner SB.

Mushroom poisoning due to amatoxin. Northern California, Winter — West J Med. CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar. Beug MW, Shaw M, Cochran KW. Brandenburg WE, Ward KJ. Mushroom poisoning epidemiology in the United States.

Chen ZH, Zhang P, Zhang ZG. Investigation and analysis of mushroom poisoning cases in southern China from — Fungal Divers. Article Google Scholar. Zhou J, Yuan Y, Lang N, Yin Y, Sun CY. Analysis of hazard in mushroom poisoning incidents in China mainland. Chin J Emerg Med.

in Chinese. Li HJ, Zhang HS, Zhang YZ, et al. Mushroom poisoning Outbreaks-China, China CDC weekly. China CDC Weekly. Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar. Liu ZT, Zhao J, Li JJ. Li WW, Liu ZT, Ma XC, et al.

Surveillance of foodborne disease outbreaks in China, — Food Control. Li WW, Sara MP, Liu ZT, et al. Mushroom poisoning Outbreaks-China, — Han HH, Kou BY, Ma J, et al.

Analysis of foodborne disease outbreaks in chinese mainland in Chin J Food Hyg. Li HQ, Guo YC, Song ZZ, et al. Analysis of foodborne disease outbreaks in China in Li HQ, Jia HY, Zhao S, et al. He JY, Ma L.

Investigation and treatment of four cases of mushroom poisoning in Guangzhou. CAS Google Scholar. Chen ZH, Yang ZL, Bau T et al. Beijing Sci Press. Mao XL. Poisonous mushrooms and their toxins in China. Bau T, Bao HY, Li Y.

Chen ZH. New advances in researches on poisonous mushrooms since Dai YC, Yang ZL, Cui BK et al. YAO QM, Yu CM, Li CH, et al. Analysis of epidemiological characteristics and treatment of mushroom poisoning in Chuxiong of Yunnan province.

J Clin Med. Li HJ, Zhang YZ, Liu ZT, et al. Species diversity of poisonous mushrooms causing poisoning incidents in Yunnan Province, Southwest China. Zhao J, Tang QL, Min XD, et al. Analysis on poisonous mushroom poisoning from to in Yunnan province.

Capital J Public Health. Toxicology group of emergency medicine branch of Chinese Medical Association, emergency medical doctor branch of Chinese Medical Doctor Association, poisoning and treatment Committee of Chinese Society of Toxicology. Consensus on clinical diagnosis and treatment of poisoning of mushroom contained amanitin in China.

Chin J Emerg. Google Scholar. Keller SA, Klukowska-Rötzler J, Schenk-Jaeger KM, et al. Mushroom Poisoning-A 17 year retrospective study at a Level I University Emergency Department in Switzerland. Int J Environ Res Public Health. Beug MW. Summary of the Poisoning Reports in the NAMA Case Registry for through NAMA Toxicology Reports and Poison Case Registry; Chen ZH, Hu JS, Zhang ZG, et al.

Determination and analysis of the main amatoxins and phallotoxins in 28 species of Amanita from China. Sun J, Niu YM, Zhang YT, et al. Toxicity and toxicokinetics of Amanita exitialis in beagle dogs.

Trestrail JH 3rd. Mushroom poisoning in the United States: an analysis of United States poison center data. Pajoumand A, Shadnia S, Efricheh H, et al. A retrospective study of mushroom poisoning in Iran. Schmutz M, Carron PN, Yersin B, et al. Mushroom poisoning: a retrospective study concerning years of admissions in a swiss Emergency Department.

Intern Emerg Med. Mowry JB, Spyker DA, Cantilena LR et al. Download references. This work was supported by the Major Research Plan Foundation of Yunnan Province ZF , the Special Basic Cooperative Research Programs of Yunnan Provincial Undergraduate Universities BA , and the National Natural Science Foundation of China No.

This work was supported by the Major Research Plan Foundation of Yunnan Province ZF ; the Special Basic Cooperative Research Programs of Yunnan Provincial Undergraduate Universities BA ; and the National Natural Science Foundation of China No.

Qunmei Yao and Zhijun Wu contributed equally to the work and are co-first authors of the article. National Institute for Occupational Health and Poison Control, Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Beijing, , China.

Chuxiong Yi Minority Autonomous Prefecture Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Chuxiong, , Yunnan, China. Chuxiong Health Commission, Chuxiong, , Yunnan, China. You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar. QMY led the data collection and analysis.

ZJW wrote the main manuscript. JJZ, CMY, QLH, JRH, and JPD collected the data. HJL reviewed the data. CYS led the research project. All authors reviewed the manuscript. Correspondence to Chengye Sun. All methods in this study were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4. Reprints and permissions. Yao, Q. et al. A network system for the prevention and treatment of mushroom poisoning in Chuxiong Autonomous Prefecture, Yunnan Province, China: implementation and assessment.

BMC Public Health 23 , Download citation. Received : 20 March Accepted : 02 June Published : 11 October Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:.

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative. Skip to main content.

Search all BMC articles Search. Download PDF. Abstract Background Mushroom poisoning is a major public health issue in China. Results Compared to the average fatality rate of mushroom poisoning from to , the average fatality rate from to significantly decreased from 0.

Conclusions These findings suggest that the NSPTMP effectively reduced the harm caused by mushroom poisoning. Introduction Mushroom poisoning occurs worldwide [ 1 , 2 , 3 ]. Methods Data collection To assess the impact of the NSPTMP, two distinct data resources were used.

Statistical analysis The data were analyzed using SPSS version Results Establishment of the NSPTMP in Chuxiong Prefecture, Yunnan Province The NSPTMP in Chuxiong Prefecture consists of three types of institutions arranged horizontally, namely, CDCs, hospitals, and HADs.

Poisonous mushroom sample library The National Institute of Occupational Health and Poison Control NIOHP at the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention China CDC initiated a project in to establish a poisonous mushroom sample library in regions with a high prevalence of mushroom poisoning, such as Guizhou and Yunnan provinces.

Online poisonous mushroom identification During the establishment of the national poisonous mushroom sample library, an effective online working system was developed among doctors, CDC staff, and mycologists, aided by the emergence of new communication tools, particularly the WeChat app.

Village-level clinics : These clinics should have the ability to make preliminary diagnoses of mushroom poisoning and provide simple treatment to patients, with the objective of conducting initial patient grading. Town-level hospitals : These hospitals should possess the capability to accurately categorize patients into high-, medium-, and low-risk groups and provide treatment for low-risk groups, with the aim of accepting patients with mild symptoms.

County-level hospitals : These hospitals should have the capacity to recognize patients at high, medium, and low risk and provide appropriate treatment to patients in medium- and low-risk groups.

Emergency department of the prefecture-level hospital : This department should have the capability to manage patients in all risk categories and provide guidance to lower-level hospitals on implementing standardized treatment protocols for mushroom poisoning.

Full size image. Table 1 Number of mushroom poisonings, deaths and fatalities caused by mushroom poisoning in Chuxiong Prefecture Full size table. Table 3 The hospitalization rates for different poisonous mushroom species Full size table. Discussion Various types of data resources reflect exposure to poisonous mushrooms, including health surveillance systems [ 6 , 7 , 10 ], hospital visit records [ 7 , 32 ], field surveys [ 11 ], telephone or online consultations [ 9 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 33 ], and literature reviews.

Conclusions In this paper, a network system for the prevention and treatment of mushroom poisoning was established in a high-risk area for mushroom poisoning, Chuxiong. Data Availability The data will not be shared publicly; however, the data are available upon reasonable request. Abbreviations NSPTMP: Network system for the prevention and treatment of mushroom poisoning CDC: Center for Disease Control HAD: Health administration department NIOHP: National Institute of Occupational Health and Poison Control EICU: Emergency intensive care unit.

References He MQ, Wang MQ, Chen ZH, et al. Article CAS Google Scholar Govorushko S, Rezaee R, Dumanov J, et al. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar Diaz JH. Article PubMed Google Scholar Jaeger A, Jehl F, Flesch F, Sauder P, Kopferschmitt J.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar Garcia J, Costa VM, Carvalho A. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar Wennig R, Eyer F, Schaper A, et al. Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Cervellin G, Comelli I, Rastelli G, et al. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar Yamada EG, Mohle-Boetani J, Olson KR, Werner SB.

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Beug MW, Shaw M, Cochran KW. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar Chen ZH, Zhang P, Zhang ZG. Article Google Scholar Zhou J, Yuan Y, Lang N, Yin Y, Sun CY. Article Google Scholar Li HJ, Zhang HS, Zhang YZ, et al.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Li HJ, Zhang HS, Zhang YZ, et al. Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Li HJ, Zhang HS, Zhang YZ, et al.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Liu ZT, Zhao J, Li JJ. Article CAS Google Scholar Li WW, Sara MP, Liu ZT, et al. Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Han HH, Kou BY, Ma J, et al. Article Google Scholar Li HQ, Guo YC, Song ZZ, et al. Article Google Scholar Li HQ, Jia HY, Zhao S, et al.

Article CAS Google Scholar He JY, Ma L. CAS Google Scholar Chen ZH, Yang ZL, Bau T et al. CAS Google Scholar Bau T, Bao HY, Li Y. Article CAS Google Scholar Dai YC, Yang ZL, Cui BK et al. Article Google Scholar Li HJ, Zhang YZ, Liu ZT, et al. Article Google Scholar Zhao J, Tang QL, Min XD, et al.

Article Google Scholar Toxicology group of emergency medicine branch of Chinese Medical Association, emergency medical doctor branch of Chinese Medical Doctor Association, poisoning and treatment Committee of Chinese Society of Toxicology.

Google Scholar Keller SA, Klukowska-Rötzler J, Schenk-Jaeger KM, et al. Article Google Scholar Beug MW. CAS Google Scholar Sun J, Niu YM, Zhang YT, et al.

gov means it's official. Federal Mushroom Poisoning Prevention websites often end in. gov or. Before Mushoom sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site. The site is secure. NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

Sie irren sich. Geben Sie wir werden es besprechen. Schreiben Sie mir in PM, wir werden reden.

Ich entschuldige mich, aber meiner Meinung nach lassen Sie den Fehler zu. Schreiben Sie mir in PM, wir werden besprechen.

der Fieberwahn welcher jenes

Es ist der einfach prächtige Gedanke