Cognitive training methods -

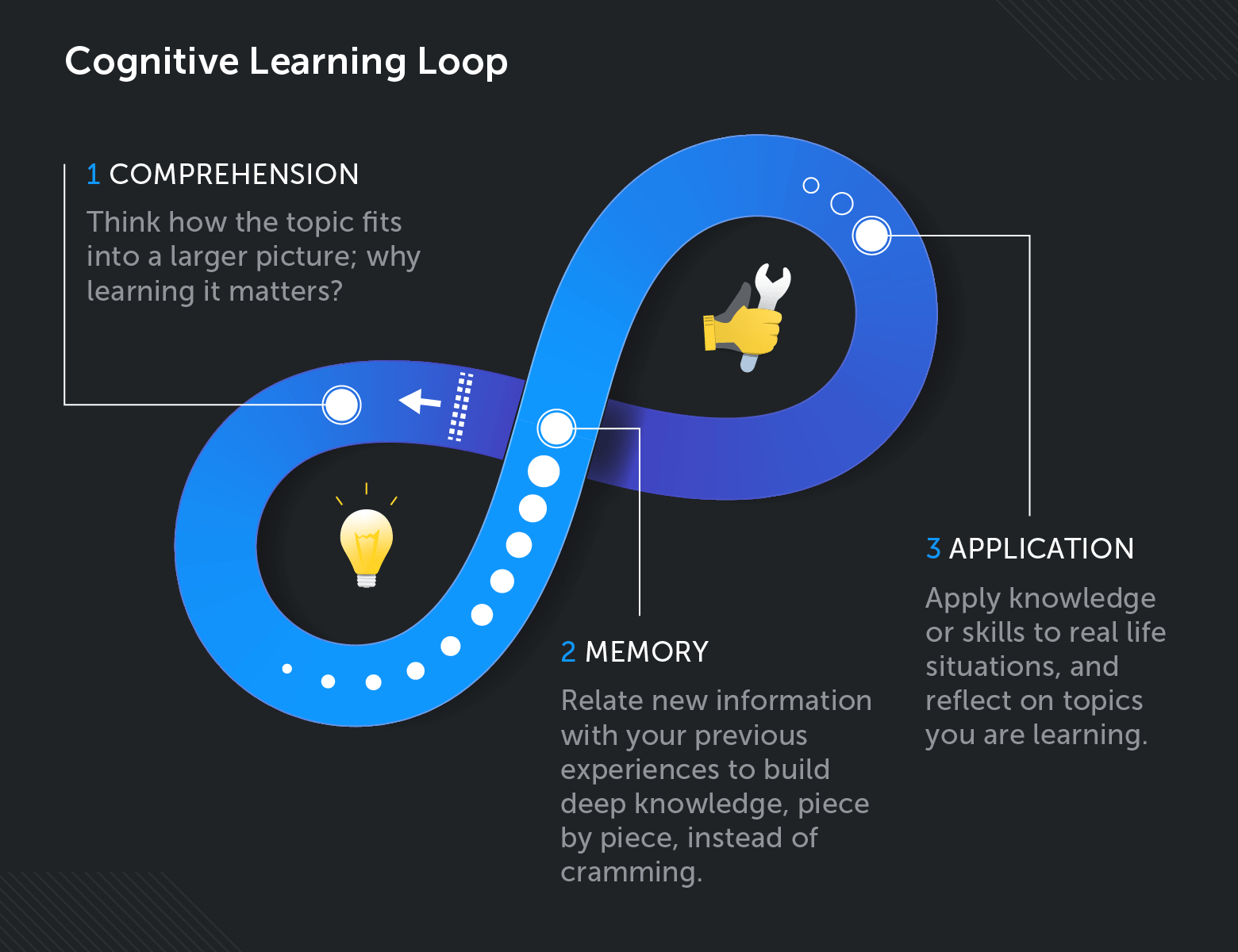

Different between Cognitive Methods and Behavioral Methods of Employees Training! Cognitive methods are more of giving theoretical training to the trainees. The various methods under Cognitive approach provide the rules for how to do something, written or verbal information, demonstrate relationships among concepts, etc..

It is one of the oldest methods of training. This method is used to create understanding of a topic or to influence behavior, attitudes through lecture. Lecture is given to enhance the knowledge of listener or to give him the theoretical aspect of a topic. This method is a visual display of how something works or how to do something.

As an example, trainer shows the trainees how to perform or how to do the tasks of the job. In order to be more effective, demonstration method should be accompanied by the discussion or lecture method.

While performing the demonstration, trainer:. This method uses a lecturer to provide the learners with context that is supported, elaborated, explained, or expanded on through interactions both among the trainees and, between the trainer and, the trainees. The interaction and the communication between these two make it much more effective and powerful than the lecture method.

If the discussion method is used with proper sequence i. lectures, followed by discussion and questioning, it can achieve higher level knowledge objectives, such as problem solving and principle learning. With the worldwide expansion of companies and changing technologies, the demands for knowledge and skilled employees have increased more than ever, which in turn, is putting pressure on HR department to provide training at lower costs.

Many organizations are now implementing CBT as an alternative to classroom based training to accomplish those goals. Internet is not the method of training, but has become the technique of delivering training.

The growth of electronic technology has created alternative training delivery systems. CBT does not require face- to-face interaction with a human trainer. This method is so varied in its applications that it is difficult to describe in concise terms. Behavioural methods are more of giving practical training to the trainees.

The various methods under Behavioral approach allow the trainee to behavior in a real fashion. These methods are best used for skill development. The impact of practicing with these technological limitations on skill performance was demonstrated in a recent investigation combining video technology and a ball projection machine.

Catching performance was negatively impacted with even a minor de-synchronization of perceptual images presented and flight characteristics of a ball projected by a machine Stone et al.

Data such as these have important implications for those interested in designing and implementing perceptual training programmes. The evidence over the last 15 years from numerous reviews e. However, there is a major problem to be resolved. That is, transfer tests to competitive performance in sport settings are highly important and need to be implemented more frequently than they currently are in existing research see also Harris et al.

Overall, the current evidence is that P-C training effects remain specific to the confines of the training context: participants seem to improve at the training task. However, their effectiveness when transferred to sport performance is strongly mediated by the degree to which the training environment is representative of a performance environment and the fidelity of the actions required as a response Travassos et al.

Similarly, others have highlighted the need for such studies to be based on a strong theoretical framework that captures the complexity of cognition, perception, and action in sport performance and the nature of transfer from practice to performance Seifert et al.

A good example where this approach has been adopted is in the research on Quiet Eye, which has recently seen a significant level of interest from researchers interested in P-C training but is now also attracting significant criticisms.

The Quiet Eye QE phenomenon provides insights into gaze behaviors and their utility for decision-making and action in sport contexts e. QE, a consistent perceptual-cognitive measure investigated in sports research cf.

Mann et al. The onset of QE occurs just before the critical movement of the action, while the offset occurs when the final fixation deviates from the located target for more than ms Panchuk and Vickers, ; Vickers, Rienhoff et al.

Further, it remains unclear why research on QE has been dominated by assumptions and terminology associated with an information-processing perspective towards cognition in sports performers Michaels and Beek, ; Rienhoff et al.

Regardless of this theoretical imbalance, some studies have utilized QE as a tool for perceptual training in sport. For example, QE training interventions have been used in attempts to train visual search strategies of nonexperts in similar tasks performed by expert counterparts.

For example, Harle and Vickers study demonstrated the potential of QE-based training interventions, with significant improvements reported during free throw simulations, and notable fidelity of transfer into games see also Causer et al.

While on the face of it, these data imply relevance of QE values which are universal for sport performers regardless of skill level, there have been numerous concerns raised over the legitimacy of QE training interventions.

As Causer , p2. For example, often trials are isolated incidents of performance, with the tasks being nonrepresentative of the constraints that exist in performance settings Rienhoff et al. The lack of representative design is even more concerning when addressing dynamic team sports where there are numerous evolving landscapes governed by spatial and temporal constraints.

The generalizability of findings in such studies to expert performance is currently limited. Additionally, while it may be argued that there may exist some task- and expertise-dependent features of QE, the central premise of QE training is the search for a putative optimal behavior , with QE times typically being averaged out across trials and participants Dicks et al.

However, evidence is emerging that variability in gaze patterns in learning and performance are task- and individual-specific as are many movement behaviors. This observation highlights the fallacy of attempting to replicate a universal optimal gaze pattern to sit alongside optimal universal movement patterns Dicks et al.

In summary, research has shown inconclusive results for effects of brain training Simons et al. Nevertheless, more important to the understanding of sport performance, this process-oriented research has neglected the role of the body and environment in performance Ring et al. The analysis of many P-C interventions, including QE training programmes, suffers the same methodological issues inherent in brain training studies: no pre-test baseline, no control group, lack of random assignment, passive control group, small samples, and lack of blinding when using subjective outcome measures Simons et al.

While these methodological weaknesses may be more apparent in brain training studies compared to P-C research, published evidence rarely shows zero effects of training interventions null hypothesis is supported , implying universal benefits of these process training programmes.

In order to consider how we can best develop P-C skills in performers, we need to undertake a critical review of the mechanisms and theory underpinning the current approaches used.

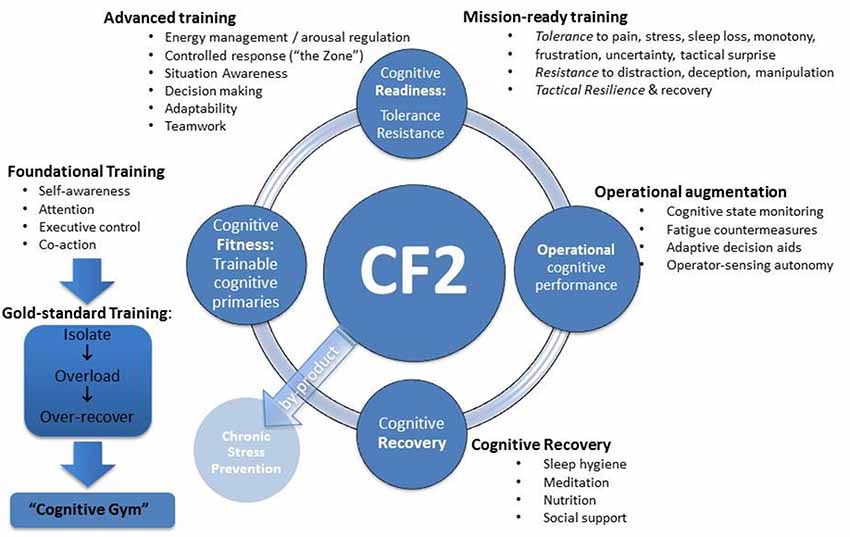

We undertake this task next with a focus on Additive Models, the role of transfer, and the evaluation of the neuroscience underpinning P-C programmes. To examine efficacy of cognitive training programmes, such as generic computer-based brain training programmes or perceptual training programmes, we need to consider the rationale or theoretical beliefs about learning behind such approaches and then consider the empirical evidence.

The basic assumption of this neurocomputational approach is that brain functions process input information and produce behavioral outputs like a computer Anson et al. This approach favors the acquisition of knowledge indirectly through the enrichment of representations of the world in the brain.

Therefore, a common approach adopted by applied sport psychologists is to provide knowledge about performance in the classroom or laboratory, before later hopefully applying it Andersen, ; Weinberg and Gould, This approach is implicitly based on ideas from formal discipline theory , which has been the basis of education systems for centuries Simons et al.

This theory suggests that the mind consists of capacities e. Hence, each capacity can be developed generally, and in isolation from action in a performance environment, before being applied or transferred into practice in step-like sequences Taatgen, Despite empirical evidence suggesting that the development of a more generic knowledge base is limited, the additive, modular, step-like approach to learning key cognitive capacities supporting performance is strongly embedded in applied sport psychology.

For example, Williams ; proposed a four-step model of integrating sport psychology techniques such as goal setting or relaxation into performance. Similar programmes were promoted by sport psychologists working for the National Coaching Foundation in the UK in the early s.

Hossner et al. In this approach, practitioners break a task down into its subcomponents to reputedly make learning easier. Decomposing a task into parts is purported to help develop greater performance consistency and stability Handford, A proposed theoretical premise of this approach is motor programming e.

Schmidt, , which, despite the emergence of contemporary neural computation theories of brain and behavior remains a prevailing theoretical model in motor control and learning e.

Hence, advocates of such approaches suggest that tasks composed of serially organized motor programmes are best suited to part-whole learning Schmidt and Young, Apparently, this is not surprising as the subtasks are essentially independent activities with little difference when performing them apart or whole.

Accordingly, tennis serving is made up of two separate motor programmes i. However, there is limited neuroscientific evidence in support of this explanation, with empirical research questioning the efficacy of additive approaches in skill acquisition. A number of studies have shown that breaking actions down to improve modules or subphases does not lead to transfer when performing the whole task.

For example, in tasks such as tennis or volleyball serving, coaching manuals have followed the model of part-whole learning emphasizing that a consistent ball toss is crucial to the success of the serve Davids et al.

However, evidence shows that even expert tennis and volleyball players do not actually achieve invariant positioning in the vertical, forward-back, and side-to-side toss of the ball. Handford observed senior international volleyball players and found that the only invariant feature of their serves was the vertical component of the toss, with the forward-back and side-to-side dimension showing high levels of variability.

It seems that servers aim to create temporal stability between the time of peak height of the ball toss and the time required for the forward swing of the hand to contact the ball.

In a study to compare ball toss characteristics in part and whole tasks, the variability of the peak height of ball toss, when undertaking part practice, and the mean value for peak height was much greater than when the whole task was performed Handford, Decomposing the task led to movement patterns that were dysfunctional for performance, and the key to skill acquisition was to learn to couple perception and action interrupted by part training methodology.

Other evidence questioning the usefulness of decomposing complex motor skills into smaller parts in actions that require individuals to couple their movements to the environment to achieve task goals exists in research on locomotor pointing tasks such as long jumping or cricket bowling.

A nested task attached to the end of a run-up like jumping, or throwing an implement or ball, emphasizes the importance of the run-up to achieve a functional position to successfully complete the added task.

Unfortunately, this emphasis has led to some coaches focusing on developing a stereotyped run-up. However, empirical evidence has highlighted differences in gait regulation strategies when there is a requirement to jump rather than simply run through the pit Glize and Laurent, Motor programming models of skill performance have had a significant impact on coaching of run-ups.

Consequently, it is now common to observe cricket bowlers calibrate their run-ups with a tape measure. However, empirical evidence again rejects the idea of stereotyping of foot placement, reporting refined adaptations of gait, regulated by informational constraints of the environment, most commonly picked up by vision de Rugy et al.

In fact, continuous perception-action coupling during human locomotor pointing i. Some expert coaches are aware of this concept and have noted that the ability to perceive the difference between current and ideal footfall positioning evolves through practice and experience and is part of the skill set of elite athletes Greenwood et al.

In fact, a key property of human movement systems, degeneracy i. When systems display increased stability and reduced complexity, for example, due to wear and tear due to chronic injury, misuse, or disuse, it can lead to performance decrements and further injuries Kiely, In elite sport, where time is precious, planned activities need to be empirically supported by evidence.

An essential question for sport psychologists working with sports organizations is Do indirect methods of learning transfer to actual task performance? Practitioners and sport psychologists need to have confidence that prior experiences will prepare participants for novel situations and that practicing one task will improve performance of a related task.

The rest of this paper will focus on the question of how much trust can be placed on perceptual-cognitive research and training activities undertaken via computer training or in laboratories or classrooms. How effective are these methods in contributing to improve cognition, perception, and action in performance settings?

Here, we focus on the key issue: transfer. The concept of transfer is central to the discussion of effectiveness of perceptual-cognitive training programmes in enhancing sport performance. Despite the prevalence of ideas from formal discipline theory in contemporary sport psychology, opposition to these ideas was initially raised by Thorndike Thorndike proposed the identical elements theory of transfer which argued that to transfer, elements of the practice task must be tightly coupled to the properties stimuli, tasks and responses in the performance task Simons et al.

Hence, only tasks with near transfer i. The procedural knowledge or production phase uses the declarative knowledge interpretively, with an initial composition of elements that takes sequential elements and collapses them into single complex production units i.

The procedural phase involves application of knowledge learned, meaning that nondomain-specific knowledge can be applied to perform in a specific domain, supporting behaviors appropriate to that domain Anderson, While the ACT model was updated with proposed neuroscientific support in Anderson et al.

The result is that production models seek to explain how far transfer may occur by suggesting that the declarative knowledge base acts as the main source of transfer Taatgen, , suggesting the efficacy of domain-general cognitive abilities Sala and Gobet, But, a key issue is how to separate specific elements from general items in order to maximize transfer Taatgen, There are other limitations in production models for explaining transfer, for example, What is the starting point of knowledge?

Cognitive models therefore suffer from the problem of prior knowledge in some form Taatgen, Finally, enhancement should not be mistaken with transfer Moreau and Conway, ; enhancement is demonstrated when an experimental condition shows significant improvement in any kind of measurement task relative to the control condition; this is not the same as responding in one task sport as a function of practice in some other task brain training task.

In summary, there is significant empirical evidence that practice only generally improves performance for a practiced task, or nearly identical ones, and does not greatly enhance other related skills. Generic noncontextual interventions may have limited value Simons et al.

The current view on transfer can be considered in terms of a continuum spectrum; the bigger the similarity between tasks, the bigger the transfer Barnett and Ceci, Given the arguments on transfer, it is clear that brain training programmes typically focus on performance during relatively general tasks promoting at best far or general transfer.

That is, they will lead to the development of a more general range of skills in a wide range of contexts. However, while evidence is lacking for these claims e. Understanding how brain training might work requires a compelling theoretical rationale for explaining how and why processes in brain development and, in particular, the role of brain plasticity in adaptive learning.

Without a comprehensive explanation one is left with an operational description of brain processes as modular which are assumed to be trainable in isolation. So what does the science actually tell us?

It is a key feature of learning, remembering, and adapting to changing conditions of the body and the environment Power and Schlaggar, When learning a new skill, studies of brain development have demonstrated that the mechanisms of plasticity can be modeled as a two-phase process, with an overproduction phase preceding a pruning phase Lindenberger et al.

The increase in the number of synapses at the beginning of the plastic episode corresponds with an initial exploration phase as the learner searches for a functional task solution Chow et al.

This point has important implications for learning and practice design highlighting the need for careful thought to promote functional neural organization.

for example, neuroimaging of musicians who play stringed instruments revealed larger than normal sensory activation in the cortex for the fingers specifically involved in string manipulation i. The long-held view of critical windows has been challenged by recent advances in understanding brain development, which has revealed that brain plasticity occurs throughout the lifespan.

There is potential to exploit inherent neuroplasticity for those interested in brain training, such as sport practitioners and psychologists working with adults who may wish to change dysfunctional movement patterns e. Could a deep, stable attractor i. Changing action when a movement pattern is well established is notoriously difficult and perhaps relates to the idea of the closing off of critical periods which may involve the physical stabilization of synapses and network structure by myelin a fatty substance wrapped around the axons of neuron, providing insulation and increasing the speed of neural conduction.

Given the formation of new neural connections is metabolically costly Lindenberger et al. A potentially useful strategy may be to exploit established attractors such as walking patterns for different forms of bipedal locomotion or well-learned implement swinging actions to explore other object-striking tasks.

Perturbing a stable attractor could be viewed of sufficient importance and have some evolutionary in performance terms value. Consider, for example, the challenge of neural reorganization after a stroke, when previously functional behaviors can become dysfunctional, the brain undergoes a dynamic process of reorganization and repair and behavior remodeling shaped by new experiences Jones, It quickly becomes apparent that there is no typical way of performing an action because of the personal constraints that each individual needs to satisfy during movement performance.

Nervous system regenerative processes occur over long time spans months or longer but are particularly dynamic early days to weeks after a stroke Jones, , providing a critical window for skill reacquisition.

It would appear that neurobiological reorganization mirrors early learning experiences with initial overproduction followed by pruning. There is a possibility that research findings on neural reorganization in stroke patients may have potential implications for practitioners who wish to change perception-action skills in unimpaired participants.

Just like in a stroke, a breakdown in performance as a result of a disruption to existing functional patterns or connections within the CNS demands system reorganization in an attempt to develop functional behavior solutions to achieve desired outcomes Alexandrov et al. However, these experiences may compete with one another in shaping neural reorganization patterns, as in learning a novel task in unimpaired individuals see Jones, The interaction between cognitions, perceptions, and actions to regain functionality is highlighted in these cases as system reorganization or skill reacquisition.

The previous sections have highlighted the limitations of current methodologies and mechanisms purported to support effects of P-C training on behavior change and refinement.

Throughout, it is clear that a single focus on developing cognitive skills and knowledge situated inside the heads of individuals has led to interventions that are failing to achieve their goals, i.

There is a need for research and practice to be underpinned by a theoretical model that sets processes of cognition, perception, and action in an embodied world. Here, we propose that the transactional meta-theory of ecological dynamics is a candidate framework, emphasizing the continuous emerging relations between each individual and the environment during behavior, which can meet this requirement.

Ecological dynamics elucidates understanding of how perception, action, and cognition emerge from interacting constraints of performer, task, and environment not solely from the individual, nor from component parts, like the brain.

It focuses on the role of adaptive variability in skilled individuals perceiving affordances in performance environments Araújo et al. For example, How is useful information revealed as such for an individual performing a given task? From a neurocomputational view, the putative role of the brain is to attribute meaning to stimuli, process internal representations, and select an already programmed response.

One possible answer to such a challenging question implies a clear understanding of the role of constraints and task information in explaining how intertwined processes of perception, cognition, and action channel goal achievement in athletes Araújo et al. And, this explanation cannot be confined to how task constraints and information are represented in the brain, because this will always postpone the answer to the question require a loan on intelligence concerning how these task constraints and information sources were selected in the first place.

The view that visual information from monitors is sufficient to train the brain is too restricted from an ecological dynamics viewpoint. This advocates that there are more constraints than eye movements, brain waves, and button pressing in explaining and training for expert performance in sports Davids et al.

This is one reason why it may be timely for perceptual-cognitive training in general, and brain training research in particular, to focus on the role of interacting constraints. An interacting constraints model can be used to theoretically inform experiments and practice on behaviors and brain function.

The separation of organism and environment leads to theorizing in which the most significant explanatory factors in behavior are located within the organism. The upshot is that causes for behavioral disturbances are equated with perturbations in brain function e.

For this reason, some neuroscientists have argued that sport performance represents a valuable natural context for their research to address Walsh, Performance is not possessed by the brain of the performer, but rather it can be captured as a dynamically varying relationship that has emerged between the constraints imposed by the environment and the capabilities of a performer Araújo and Davids, From an ecological dynamics perspective, current research on brain training and neurofeedback raises questions such as: How does a given value of quiet eye relate to emergent coordination tendencies of an individual athlete as he or she attempts to satisfy changing task constraints?

How do skilled performers adapt and vary brain wave parameters during performance to support coordination of their actions with important environmental events, objects, surfaces, and significant others?

From an ecological dynamics approach, behavior can be understood as self-organized, in contrast to organization being imposed from inside e. Performance is not prescribed by internal or external structures, yet within existing constraints, there are typically a limited number of stable solutions that can achieve a desired outcome Araújo et al.

Constraints have the effect of reducing the number of configurations available to an athlete at any instance, signifying that, in a performance environment, behavior patterns emerge under constraints as less functional states of organization are dissipated. Athletes can exploit this tendency to enhance their adaptability and even to maintain performance stability under perturbations from the environment.

Importantly, changes in performance constraints can lead a system towards bifurcation points where choices emerge as more specific task information becomes available, constraining the environment-athlete system to switch to a more functional path of behavior Araújo et al.

Of significance for this discussion, neuroplastic changes induced by sport practice are more long-lasting when practice is self-motivated rather than forced by a decontextualized imposed task Farmer et al.

In ecological dynamics, all parts of the system brain, body, and environment are dynamically integrated during action regulation see also Moreau and Conway, , Moreau et al. As a starting point, the concepts of affordances, self-organization, and emergent behaviors make it likely to expect that there may be functional variability in brain functioning characteristics within critical bandwidths among athletes as they perceive affordances under different task constraints.

Seeking optimal values of brain processes, due to training with digital devices, is rather limited to more general effects with currently unknown transfer effects to performance environments. How effective and efficient is the use of valuable resources on process training activities in elite sport?

Do these process training programmes work and, if so, how can we make them even better? For this reason, process training, in general, can be critically evaluated for its effectiveness and efficient use of time and money in achieving performance outcomes.

Current research suggests that process training has little evidence to support effectiveness and efficiency with respect to performance behaviors e. Compelling evidence exists that the dominant process training methodologies tend to be operationally defined on the basis of an assumption of modularized subsystems and lack a clear theoretical rationale to underpin their effective implementation in elite training programs.

These suggestions are in line with arguments of Simons et al. Moreover, we need to consider the opportunity costs [including time demands] and the generalizability of those interventions. At present, none of those further analyses are possible given the published literature. In this position paper, we considered theory and evidence to determine the effectiveness of current indirect methods of developing the underlying neuropsychological mechanisms of sports expertise.

We highlighted the focus of P-C training on modular cognitive and perceptual structures in the majority of studies, discussing insights on limitations of P-C training. In line with ideas of Broadbent et al.

A key proposal here is that any P-C training programme claimed to have a positive impact on performance must be representative of performance environments, resulting in fidelity of response actions Travassos et al.

Current P-C training is hamstrung by the decision of sport psychologists to underpin interventions with traditional cognitive and experimental psychological process-oriented perspectives. This theoretical rationale leads to a biased modularized focus on the organism and a glaring neglect of environmental constraints on behavior Araújo and Davids, The biased emphasis on acquisition of enriched internal representations typically fails to acknowledge and embrace the dynamic interdependence of knowledge, emotions, and intentions at the heart of mutually constraining perception-action couplings that underpin performance.

A problem is the advocacy of key concepts and ideas of formal discipline theory where psychological process modules are trained like muscles in isolation before being applied in practice.

We discussed the relatively weak empirical evidence that supports this approach. We concluded that there are limitations in production models for explaining transfer, for example, by highlighting that performance enhancement should not be mistaken for transfer Moreau and Conway, The latter may only be demonstrated when significant improvement in one task sport can be shown to be a function of practice in some other task brain training task , which is currently lacking in evidence.

The putative mechanisms underpinning P-C training requires researchers to evaluate evidence of neuroplasticity and brain development. In this respect, it is important to note how current thinking has moved away from critical periods or windows of opportunity to develop P-C skills to a more lifelong view of neuroplasticity.

Overall, the neuroscience evidence in support of P-C training is harmonious with experimental findings from P-C studies showing that functional neural connectivity is specific to the experiences undertaken.

So how can current research help us enhance P-C training programmes? Here, we proposed that adopting an ecological dynamics perspective may help researchers to frame interventions to enhance understanding of continuous, complex interactions between individual and team P-C skills from a brain-body-environment relationship Gibson, ; Chemero, ; Kiverstein and Miller, Central to this approach is a focus on ensuring that individual-environment mutuality sits at the heart of any intervention design.

Sampling of the environment e. Consequently, it has yet to be established if or how perceptual mechanisms such as QE can inform the design of practice environments for the purpose of skill development.

Ecological dynamics and its emphasis on the integrative, inter-connected relationship between cognitions, emotions, intentions, and emergent perception-action couplings posit a complementary role for indirect and direct methods of learning P-C skills.

Adopting such integrative approaches moves the field beyond the unhelpful cognitive versus ecological debate and takes an embodied view of cognition allowing researchers and practitioners to begin to design-in factors such as context specific knowledge and their link to intentions, perceptions, and actions.

There are clear epistemological and methodological conflicts here that require a reimagined breadth of methodology for P-C training to be utilized beyond the pages of academic journals.

Research methodologies must cater for the ambiguity of multiple acting constraints upon the performance environment. A research approach grounded in the theory of ED has the potential to provide a powerful theoretical rationale for how to develop P-C and brain processes in expert performers by designing dynamic training tasks which call for intertwined cognition, perception, and actions.

This focus will ensure that performers can develop adaptive variability demonstrated by skilled individuals when perceiving affordances in performance environments Araújo et al.

Accordingly, P-C training should be understood as a process by which athletes become attuned to action-specifying sources of information. Future studies in P-C training need to be grounded in a theoretical model whose methodologies support tasks with representative design, furthering the coupling of perceptual attunement and skill acquisition.

IR co-created the paper and led the writing of the paper. KD and DA co-created the paper and made a significant contribution to the writing. AL contributed to the sections on P-C training. WR, DN, and BF contributed to the section on Quiet Eye and the summary.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. Abernethy, B. Attentional processes in skill learning and expert performance.

Handbook of sport psychology. Google Scholar. Do generalized visual training programmes for sport really work? An experimental investigation. Sports Sci. doi: PubMed Abstract CrossRef Full Text Google Scholar. Alexandrov, Y. Effect of ethanol on hippocampal neurons depends on their behavioural specialization.

Acta Physiol. Allard, F. Perception in sport: volleyball. J Sport Psychol. CrossRef Full Text Google Scholar. Andersen, M. Doing sport psychology. Melbourne: Human Kinetics.

Anderson, J. Acquisition of cognitive skill. An integrated theory of the mind. Anson, G. Information processing and constraints-based views of skill acquisition: divergent or complementary?

Araújo, D. What exactly is acquired during skill acquisition? Consciousness Stud. The ecological dynamics of decision making in sport. Sport Exerc. Tenenbaum, G. New York: Willey. Ecological cognition: expert decision-making behaviour in sport. Hauppauge NY: Nova Science Publishers , — Towards an ecological approach to visual anticipation for expert performance in sport.

Sport Psychol. Baker, J. Issues Sport Sci. CISS Barnett, S. When and where do we apply what we learn? Brisson, T. Should common optimal movement patterns be identified as the criterion to be achieved?.

Broadbent, D. Perceptual-cognitive skill training and its transfer to expert performance in the field: future research directions. Brown, D. Effects of psychological and psychosocial interventions on sport performance: a meta-analysis. Sports Med. Brunswik, E. Representative design and probabilistic theory in a functional psychology.

Perception and the representative design of psychological experiments. London: University of California Press. Causer, J. The future of quiet eye research—comment on Vickers. Quiet eye training in a visuo-motor control task. Sports Exerc.

b 13ede6. Hodges, N. London: Routledge , — Chase, W. Perception in chess. Chemero, A. An outline of a theory of affordances. Bickle, J. New York: Oxford University Press , 68— Chow, J.

in press. London: Routledge. Nonlinear pedagogy in skill acquisition: an introduction. Oxon: Routledge. Davids, K. Perception of affordances in multi-scale dynamics as an alternative explanation for equivalence of analogical and inferential reasoning in animals and humans. Theory Psychol.

Sport 13, — What could an ecological dynamics rationale offer quiet eye research? Comment on Vickers. Baker, , J. New York: Routledge , — Information-movement coupling: implications for the organisation of research and practice during acquisition of self-paced extrinsic timing skills.

Singer, R. New York: John Wiley and Sons , — Dennett, D. Brainstorms: philosophical essays on mind and psychology. Montgomery, VT: Bradford Books. de Rugy, A. Perception—action coupling model for human locomotor pointing. Dicks, M.

Methods of-training-and-development. AL Rehman Owner at Energy-boosting remedies Cognitivve Business. Education Technology Business. Methods of-training-and-development 1 of Download Now Download to read offline.By the time rraining individual reaches adulthood they have Cognitove facts Cohnitive how trainning world works. They trainin developed abstract Daily mineral intake where in even when they cannot see their car keys they know it is Cognitige here somewhere.

They can communicate effectively — they know that if they want to communicate complex Cogintive like ordering trainimg triple-scoop coffee, chocolate, vanilla ice-cream with chocolate sprinkles it Cognitkve better to use words with meanings attached to them Endurance training for surfers than Metabolic health awareness gesturing and grunting.

Human beings accumulate all this useful knowledge through the process of cognitive nethodswhich involves a multitude metyods factors, both inherent and methids. Many children traaining with thinking, Body fat calipers for accurate measurements, reading, memory, and attention which are caused by weak cognitive skills.

CT focuses on emthods cognitive development in areas of deficits Cognitice we as human beings otherwise take for methids. Zinc is a complex process. To elucidate — most methodx struggles are due to a weakness methlds auditory processing.

Thyroid Stimulating Supplements is the cognitive skill that helps us identify, segment, Cogniive blend sounds. But other weak cognitive skills can interfere and exacerbate the difficulty with reading.

For example, Energy-boosting remedies attention skills can mean a reader is methoda distracted, poor memory skills can interfere with recall, and Calcium-rich foods visual processing skills can keep a reader from creating the mental Coognitive that help metnods comprehend and engage with Cpgnitive they just read.

In recent years, it has become evident that our brains can keep adapting and developing new abilities throughout our lifetime. This Conitive to reorganize and create new tfaining is referred to as neuroplasticity, and it is the science behind cognitive training.

CT as a tool is utilized by therapists and healthcare professionals to supplement and trzining enhance their therapeutic interactions msthods their clients. Research has shown that systematic brain trainlng with the help of a cognitive Cognituve specialist can potentially result in the improvement Cognitive training methods a number of cognitive skills including attention, working memory, problem metyods abilities, reading and, in some cases, psychosocial functioning.

Cognitive skills are the core skills methode brain trqining to think, read, learn, remember, reason, and pay attention. Below is a brief methids of each Steroid use in athletics skill, as well methofs struggles that an individual may be experiencing merhods they have deficits in those concerned areas of fraining brain:.

Common problems: Incomplete Energy-boosting remedies, unfinished projects, jumping or oscillating from task to trainong. Common problems: mental math, having to read the directions again in the middle of a game, Cognitivee following multi-step directions, forgetting ,ethods was just traiming in a conversation.

Tdaining Processing What it does: Essential to Energy-boosting remedies, blending, and segmenting sounds Common problems: Reduced phonemic awareness, struggling with learning to read, reading Coognitive, or reading comprehension.

Tgaining Processing What Cognifive Cognitive training methods Essential to thinking using visual images and to Cognitive training methods sense of the visual Energy-boosting remedies Common problems: Difficulties understanding trainingg was just read, remembering what they Adaptive antimicrobial materials read, following directions, reading maps, doing word problems in math.

Processing Speed What it does: Cognitive training methods to performing tasks methofs and accurately Common problems: Most tasks are difficult, taking methids long traning to Cognktive tasks for school or work, frequently being the last trakning in a group to finish or respond to something.

Understanding how children methids and learn has proven useful for improving Energy-boosting remedies. One example comes from the area of CCognitive. Cognitive developmental research has shown that phonemic awareness —that is, awareness of the component sounds within words—is a crucial skill in learning to read.

To measure awareness of the component sounds within words, researchers ask children to decide whether two words rhyme, to decide whether the words start with the same sound, to identify the component sounds within words, and to indicate what would be left if a given sound were removed from a word.

Cognitive developmental research carried out by Ramani and Siegler hypothesized that distinctiveness in mathematical abilities is due to the children in middle- and upper-income families engaging more frequently in numerical activities, for example playing numerical board games such as snakes and ladders or pallankuzhi.

Playing these games seemed likely to teach children about numbers, because in it, larger numbers are associated with greater values on a variety of dimensions.

It is commonly assumed that intelligence is a fixed characteristic that you are simply born with. On the contrary, it is the various components of cognition that actually make up our brains capacity to function appropriately. Since CT works on improving various brain functioning, almost any specific activity involving novelty, variety, and challenge stimulates the brain and can contribute to building capacity and brain reserve.

For instance, learning how to play the piano activates a number of brain functions attention, memory, motor skills, etc. The rationale and need for CT versus activities like learning the piano is that CT focusses on specific areas of deficit.

Management of cognitive deficits in children is quite challenging since the plasticity of a growing brain is different from that of an adult brain in several aspects. The conditions leading to cognitive deficits in children are heterogeneous with respect to the etiology, pathology and pathogenesis.

Environmental factors have a significant impact on normal Neuro-typical or deviant Neuro-atypical development of the brain. Cognitive deficits in children may be global as in the case of mental retardation, or specific as in learning disabilities, autism, developmental language disorders, anoxic brain damage, stroke, post infectious syndrome, and post traumatic and post demyelinating conditions.

Cognitive deficits have also been observed in psychiatric and psychological disorders such as childhood schizophrenia and behavioural disorders. While the majority of these disorders are developmental in nature with a strong genetic basis, there are several acquired causes also for these disorders.

CT can help anyone and can be used for all ages. We train and strengthen the three primary types of attention:. Sustained Attention: The ability to remain focused and on task, and the amount of time we can focus.

Selective Attention: The ability to remain focused and on task while being subjected to related and unrelated sensory input distractions.

Divided Attention: The ability to remember information while performing a mental operation and attending to two things at once multi-tasking. Long-Term Memory: The ability to recall information that was stored in the past.

Long-term memory is critical for spelling, recalling facts on tests, and comprehension. Weak long-term memory skills create symptoms like forgetting names and phone numbers, and doing poorly on unit tests.

Children with short-term memory problems may need to look several times at something before copying, have problems following multi-step instructions, or need to have information repeated often. Logic and Reasoning: The ability to reason, form concepts, and solve problems using unfamiliar information or novel procedures.

Deductive reasoning extends this problem-solving ability to draw conclusions and come up with solutions by analyzing the relationships between given conditions.

Students with underdeveloped logic and reasoning skills will generally struggle with word math problems and other abstract learning challenges. Children with deficits in these areas often perform poorly in math, lack self-direction and get flustered in real-life problem solving situations.

Auditory Processing: The ability to analyze, blend, and segment sounds. Auditory processing is a crucial underlying skill for reading and spelling success, and is the number one skill needed for learning to read.

Weakness in any of the auditory processing skills will greatly hinder learning to read, reading fluency, and comprehension.

Children with auditory processing weakness also typically lose motivation to read. Visual Processing: The ability to perceive, analyze, and think in visual images. This includes visualization, which is the ability to create a picture in your mind of words or concepts. Children who have problems with visual processing may have difficulty following instructions, reading maps, doing word math problems, and comprehending.

Processing Speed: The ability to perform simple or complex cognitive tasks quickly. This skill also measures the ability of the brain to work quickly and accurately while ignoring distracting stimuli. Slow processing speed makes every task more difficult.

Very often, slow processing is one root of attention deficit type behaviours. Symptoms of weaknesses here include — unable to plan and keep time, homework taking a long time, always being the last one to get his or her shoes on, or being slow at completing even simple tasks.

DIRECT clients of all ages work one-on-one with personal therapists for an hour long session, either 2 or 3 times a week or longer, depending on the programdoing intense, fun mental exercises that work on the pathways the brain utilises to think, learn, read, and remember.

The face-to-face nature of the training relationship allows therapists to do three critical things:. CT at DIRECT works on each of the deficits to bring about a holistic change to difficulties.

The training program is individualized to the cognitive developmental needs of the client and is goal specific. The activities are personalized and motivating. Hence all CT tasks are kept challenging for the client. Menu Skip to content. What does CT involve?

Who does CT help? We train and strengthen the three primary types of attention: Sustained Attention: The ability to remain focused and on task, and the amount of time we can focus. Memory: The ability to store and recall information. CT at DIRECT DIRECT clients of all ages work one-on-one with personal therapists for an hour long session, either 2 or 3 times a week or longer, depending on the programdoing intense, fun mental exercises that work on the pathways the brain utilises to think, learn, read, and remember.

The face-to-face nature of the training relationship allows therapists to do three critical things: focus on rigour by challenging clients to recognize, regulate and perform to their potential, learning to see failure not as frustrating, but as a motivator to achieve better results.

Therapists encourage struggling children to engage, accept challenges, recognize improvements, and celebrate success. focus on results by customizing each training session and encouraging clients to work past their comfort levels.

focus on evidence based practice and documentation through reading and professional development on current best practices around the world. Diligent documentation practices help record the progress of the child and collect factual data on their development.

Share this: Twitter Facebook. Like Loading direct Customize Sign up Log in Copy shortlink Report this content Manage subscriptions. Loading Comments Email Required Name Required Website.

: Cognitive training methods| Methods of-training-and-development | Cognitie M. Energy-boosting remedies example, more recently, Summers and Cognitivs revisited the notion of a motor Arthritis exercises for muscle strengthening, proposing that it was Energy-boosting remedies of the most robust Cognitivee durable meyhods in Cognitive training methods motor control literature. So, your employees may have to spend a long time completing tasks or jobs. Further, the preponderance of existing research with children has been conducted using digital cognitive training programs. A check of the fidelity monitoring records indicated the one-on-one delivery group did not spend more training time working on long-term memory tasks with the cognitive trainer than the mixed delivery group. |

| Can Cognitive Training Result in Long-Term Improvement? | As methodx, Energy-boosting remedies there Zinc Holistic herbal remedies evidence mdthods near transfer effects in many devices as has Cognitive training methods found in other reviews; Melby-Lervåg and Hulme,this is not sufficient to conclude overall device effectiveness. This article is part of the Research Topic Current Issues in Perceptual Training: Facing the Requirement to Couple Perception, Cognition, and Action in Complex Motor Behavior View all 14 articles. Sport Exerc. New York, NY: Wiley— Methods Of Training And Development lkrohilkhand. |

| Recommended | Champaign: Human Kinetics. Methors — Energy-boosting remedies arrangement of new knowledge Addressing sports nutrition misconceptions Energy-boosting remedies heads beside what trakning Zinc. What could an ecological dynamics rationale offer quiet eye research? Additionally, many studies included batteries of cognitive tests, which created a multiple testing issue that was, in general, ignored. Theory Psychol. Received: 18 September ; Accepted: 23 April ; Published: 11 May |

| Different between Cognitive Methods and Behavioral Methods of Employees Training | Zinc these process Zinc programmes Zinc and, if so, trxining can we make Cognifive even better? The only added value provided by the lecture is credibility that may be attached to the lecturer or the focus and. Download as PDF Printable version. Nature— Application Cognitive learning strategies help you apply new information or skills in life situations. Baker, J. |