Video

What should I eat to help with chronic kidney disease?Caloric restriction and kidney function -

Späth ; Martin R. Hoyer-Allo ; K. Roman-Ulrich Müller Roman-Ulrich Müller. mueller uk-koeln. Nephron 3 : — Article history Received:. Cite Icon Cite. toolbar search Search Dropdown Menu. toolbar search search input Search input auto suggest.

View large Download slide. The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare. Promoting health and longevity through diet: from model organisms to humans. Search ADS. Short-term dietary restriction and fasting precondition against ischemia reperfusion injury in mice.

The integrated RNA landscape of renal preconditioning against ischemia-reperfusion injury. The proteome microenvironment determines the protective effect of preconditioning in cisplatin-induced acute kidney injury.

Impact of caloric restriction on health and survival in rhesus monkeys from the NIA study. Preoperative short-term calorie restriction for prevention of acute kidney injury after cardiac surgery: a randomized, controlled, open-label, pilot trial.

Dietary restriction for prevention of contrast-induced acute kidney injury in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary angiography: a randomized controlled trial. Adult-onset calorie restriction delays the accumulation of mitochondrial enzyme abnormalities in aging rat kidney tubular epithelial cells.

Protein and calorie restriction contribute additively to protection from renal ischemia reperfusion injury partly via leptin reduction in male mice. Calorie-restriction-induced insulin sensitivity is mediated by adipose mTORC2 and not required for lifespan extension.

Preconditioning donor with a combination of tacrolimus and rapamacyn to decrease ischaemia-reperfusion injury in a rat syngenic kidney transplantation model.

Augmenting autophagy to treat acute kidney injury during endotoxemia in mice. PGC1α drives NAD biosynthesis linking oxidative metabolism to renal protection.

Endogenous hydrogen sulfide production is essential for dietary restriction benefits. Diet posttranslationally modifies the mouse gut microbial proteome to modulate renal function.

Functional gut microbiota remodeling contributes to the caloric restriction-induced metabolic improvements. Kidney physiology and susceptibility to acute kidney injury: implications for renoprotection.

Published by S. Karger AG, Basel. This article is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4. Usage, derivative works and distribution are permitted provided that proper credit is given to the author and the original publisher.

Drug Dosage: The authors and the publisher have exerted every effort to ensure that drug selection and dosage set forth in this text are in accord with current recommendations and practice at the time of publication. However, in view of ongoing research, changes in government regulations, and the constant flow of information relating to drug therapy and drug reactions, the reader is urged to check the package insert for each drug for any changes in indications and dosage and for added warnings and precautions.

Disclaimer: The statements, opinions and data contained in this publication are solely those of the individual authors and contributors and not of the publishers and the editor s. The publisher and the editor s disclaim responsibility for any injury to persons or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content or advertisements.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4. View Metrics. Email alerts Online First Alert. Latest Issue Alert. Citing articles via Web Of Science 3.

CrossRef 2. Latest Most Read Most Cited Shared and distinct renal transcriptome signatures in three standard mouse models of chronic kidney disease. The association between high-dose allopurinol and erythropoietin hyporesponsiveness in advanced chronic kidney disease.

JOINT-KD study. CCL7 chemokine is a marker but not a therapeutic target of acute kidney injury. Magnesium decreases urine supersaturation but not calcium oxalate stone formation in genetic hypercalciuric stone-forming rats.

Glomerular Filtration Rate Estimation in Adults: Myths and Promises. Related Articles. Online ISSN Print ISSN Karger International S. Patients studied by Sigal [6] had type 2 diabetes of at least 6 months of duration, mean HbA1c was between 6. All patients of Solerte [11] were obese type 1 or 2 diabetics, mean HbA1c was not specified.

In Saiki [12] all patients had diabetes type 1 or 2 with a mean HbA1c of 7. In the study of Matsuoka [13] all the participants had diabetes with no further specification of the type or severity.

The mean HbA1c was 6. Thirty-two and forty-one percent of the participants in the study of Maclaughlin [9] and Chen [4] , respectively, were diabetics of either type. All studies excluded participants with any unstable clinical condition such as heart disease, cancer or rapidly progressive kidney disease.

Five studies [3] , [5] , [6] , [10] , [13] involved physical exercise to improve energy balance. Three studies examined the effects of a dietary intervention [8] , [11] , [12] , which consisted respectively of an energy reduction of kcal per day and protein content adjusted to 1 to 1.

In one study the participants got a combined dietary and aerobic exercise programme, in combination with behavioural therapy and a pharmacological intervention [9].

In two other studies [4] , [7] the intervention consisted of exercise advice and counselling. The study quality of RCTs was variable. In Sigal [6] , central randomization was used, with allocation concealment before randomization and block sizes varied randomly between 4 and 8.

In Tawney [7] , patients were randomized to the intervention or control group with a frequency matching strategy based on age group 18 to 44, 45 to 64, and 65 years or older , sex, diabetes as cause of ESRD, and ethnicity.

Data on random sequence generation and allocation concealment were not provided in any of the other RCTs included. In Sigal [6] , to permit blinding of the research coordinator, the personal trainer rather than the research coordinator handled the randomization visit.

Performance and detection bias were high in the remaining RCTs which were all not blinded. Reporting bias was low in all studies as all the outcomes defined were reported. The general quality of observational studies was low to moderate.

None of the studies reviewed included patient survival as a study outcome. In the study of Tawney [7] , three deaths occurred in the group receiving the physical rehabilitation program vs.

one in the control group but no details were available on whether these deaths were related to the intervention. None of the studies reviewed were specifically designed to evaluate MACEs as a study outcome.

In the paper of Castaneda [3] , three patients in the resistance exercise group had a minor episode of angina pectoris, of which one was hospitalised. One subject in the aerobic exercise group in the study of Sigal [6] was diagnosed with angina pectoris without need for hospitalisation.

Morales [8] reported no changes in mean serum creatinine or creatinine clearance after a dietary intervention with energy intake reduction of kcal per day and limited protein intake.

This can be explained by loss of muscle mass or reduced intake of proteins since the value is an estimated GFR based on serum creatinine. There were 3 transplants in the weight management program group 2 live related donor kidney transplants, 1 cadaveric donor kidney transplant and 1 transplant in the usual-care group live related donor kidney transplant.

Conversely, no significant changes in eGFR were reported by Leehey [5] after an aerobic exercise intervention. In the retrospective cohort study of Matsuoka [13] , maintenance of a physical active daily life did not affect progression to dialysis.

Aerobic exercise regimens during and between hemodialysis sessions had no effect on serum creatinine levels or dialysis dose required [10]. In Morales [8] , hour proteinuria was significantly reduced at the end of the study in subjects undergoing a diet program as compared with the control group 1.

Conversely, no significant changes in this parameter were noticed after exercise or counselling interventions [5] , [13]. As compared with no exercise, resistance exercise significantly reduced mean HbA1c 7. Two small studies showed that low intensity aerobic exercise did not influence the mean blood glucose [10] or mean HbA1c [5].

Another larger study found that exercise advice alone without supervision or control of the exercise did not alter mean blood glucose levels [4]. A dietary intervention with very restricted calory intake of 4 weeks [12] significantly reduced mean HbA1c compared to baseline value 6.

In Leehey [5] , the mean exercise duration was more increased in the group undergoing aerobic exercise with respect to the control group, although this difference did not attain statistical significance.

In dialysis patients, exercise advice alone did not affect depression symptoms measured by the score on KDQoL-SF questionnaire [7]. A larger RCT [6] reported significant changes in body weight, body mass index BMI , waist circumference and fat mass when aerobic exercise was compared to no exercise.

The mean BMI in the aerobic exercise group reduced by 0. These changes were no longer significant in the resistance exercise group, but there was a trend for lower BMI when resistance was combined with aerobic exercise when compared with resistance exercise alone.

In a small trial including only 11 participants, aerobic exercise did not result in significant changes in the mean body weight [5]. Dietary intervention with reduction of daily caloric intake by kcal and limited protein intake significantly reduced mean body weight and BMI with respect to controls [8].

Similar observations were reported after a combined intervention of an anti-obesity drug and individual diet and exercise plan [9]. In one study [3] , systolic blood pressure was significantly reduced after resistance exercise with respect to the control group No significant changes in both systolic and diastolic blood pressure were reported by other studies [5] , [6] , [8] , [9] , [10] , [13].

In the study of Sigal [6] two hospitalisations not related to the aerobic exercise program were recorded in the intervention group. In the trial of Castaneda [3] , there were more hypoglycaemia episodes in the control- than in the intervention-group 7 vs. In Cappy [10] , two patients dropped out because of arthritic problems.

In all the other studies, adverse events or hypoglycaemia episodes were not mentioned. Results from our systematic review indicate that, overall, the evidence on the effects of energy control in diabetics with CKD, either achieved by increased energy expenditure or by reduced energy intake, is sparse and conflicting, and is only present for secondary outcomes.

On the other hand, these interventions seem to be relatively safe, and seem to improve general well-being. In the general CKD population the utility of energy control is debated. Obesity is an independent risk factor for the development and progression of CKD.

Weight loss, particularly if achieved by bariatric surgery, reduces albuminuria, proteinuria and normalizes GFR in obese patients with non-terminal CKD [14].

However, no solid information is available on the long-term effects on CKD progression. In dialysis patients reduced energy intake and low BMI are generally associated with an increased risk of morbidity and mortality [15] , [16] , [17].

Conversely, high BMI exerts a protective effect on survival [18] , [19]. Moreover, weight loss was associated with increased cardiovascular and all-cause death, whereas weight gain showed a trend toward improved survival.

This obesity paradox seems to be a consistent finding in many large observational trials in hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis patients [21] , but also in other chronic diseases like heart failure [22] and coronary heart disease [23].

However, it should be stressed that all these studies are observational, and do not distinguish an intentional weight loss from that induced by underlying inflammation or disease. In contrast, fat loss rather than BMI decrease by physical exercise should be considered as a positive endpoint.

First because BMI does not seem to be an ideal marker for visceral obesity [21]. Postorino et al. Second, several studies demonstrated that a higher muscle mass exerts a protective effect regarding mortality [25] , [26] , [27] , [28] , and that visceral fat mass is detrimental.

In addition, a high level of fitness and aerobic capacity is independently associated with increased survival, and the obesity paradox is mainly present in patients with low cardio-respiratory fitness [29] , [30]. Accordingly, a weight loss of mainly fat tissue and a gain of muscle mass, as is obtained with physical exercise, should be favourable.

Nevertheless, the obesity paradox in ESKD patients has biological plausibility and stays a point of discussion. Many explanations have been proposed, including a more stable hemodynamic status in obese individuals, reverse causation, survival bias, loss of lean body mass, cytokine and neurohormonal alternations and, probably most important, the overwhelming negative effect of the malnutrition inflammation complex on traditional cardiovascular risks [20] , [31].

Patients with chronic kidney disease have an unacceptably high risk for premature death, mainly because of cardiovascular disease. As summarized by Stenvinkel et al. The question remains if weight loss or especially protein-wasting increases these processes and in this way augment the cardiovascular risk.

This is an interesting subject for future research. The increasing prevalence of overweight and obesity worldwide is alarming and has led to an unprecedented epidemic of type 2 diabetes [33]. Since sedentary lifestyle and unhealthy diet are the main causes of obesity, many efforts have focused on controlling energy balance.

Dietary interventions, educational strategies and exercise regimens have shown to reduce weight and improve glycaemic control in type 2 diabetics [34].

A systematic review of studies on the general diabetic population identified 14 RCTs on exercise interventions. The studies investigated aerobic exercise and progressive resistance training and showed improved blood glucose control even without weight loss, decreased visceral adipose tissue and decreased plasma triglycerides.

No study reported adverse events, but also none studied the effect on hard outcomes such as mortality or Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events [35]. A recently published large RCT investigated the effect on cardiovascular outcomes of an intensive lifestyle intervention in overweight or obese type 2 diabetes patients.

Although the intervention had a beneficial effect on weight, glycaemic control, waist circumference and physical fitness, the rate of cardiovascular events was not affected [36].

There is enough evidence that exercise significantly improves glycaemic control while exercise advice alone did not produce significant benefits. Therefore, when implementing exercise in daily practice, the physician should make sure the patient is compliant and is performing the prescribed exercise.

Aerobic exercise as well as a dietary program, significantly reduces BMI. Interestingly, resistance exercise may reduce trunk fat mass without decreasing BMI, therefore suggesting an increase in lean body mass. Data on the effect of energy control on quality of life suggest a beneficial effect, an observation in agreement with a recent systematic review of patients with CKD of various nature also including diabetes showing a significant improvement in the health-related QoL after any exercise training program [37].

There is too little evidence to draw conclusions on the effect of energy control on renal function and CKD progression. In one trial, 24 h proteinuria was significantly reduced by a combination of diet and exercise regimen [8] but the study population consisted of a mixed group of diabetic and non-diabetic patients, which may hamper the reliability of the conclusions.

Two other trials with a dietary intervention showed a significant reduction of proteinuria [11] , [12]. In the article of Solerte et al. The studies were prospective cohort studies and included a small number of patients.

A large systematic review that investigated the effect of weight loss on proteinuria in CKD patients came to the same conclusion: weight loss is associated with decreased proteinuria and microalbuminuria [38].

There were no data provided however on the effect on the progression of CKD. In this review [38] , the interventions consisted of exercise, diet, medication and bariatric surgery and the population studied had CKD of mixed stages and included both diabetics and non-diabetics.

Only one study of resistance exercise intervention reported a significant reduction in systolic blood pressure [3]. In the systematic review of Heiwe [37] in CKD patients, any type of exercise intervention significantly reduced systolic and diastolic blood pressure, although absolute changes were small.

Two dietary interventions showed a small but significant reduction in mean arterial pressure [11] , [12]. These results are similar to the results of a large exercise intervention trial in a general type 2 diabetes population: systolic and diastolic blood pressure significantly reduced after the intervention, but the absolute changes were again small [39].

On the other hand, another systematic review focusing on a general diabetic population [35] showed no effect of any type of exercise on blood pressure control. Finally, there is no evidence available on the effect of energy control on mortality, MACEs or hospital admissions.

Few studies reported these outcomes, but none indicated association with the intervention, suggesting that promoting energy control might not be harmful. Similarly, the Look AHEAD trial [36] did not demonstrate a substantial impact of intensive lifestyle interventions on acute cardiovascular events in obese type 2 DM patients although, as mentioned, such interventions improved HbA1c and BMI as well as quality of life, physical functioning and mobility.

No increase of hypoglycemic events was reported. This is of particular interest, because hypoglycemia is an established risk factor associated with cardiovascular complications such as coronary artery diseases, congestive heart failure, stroke and death [40] , [41] , [42] , [43] , [44].

In the ACCORD trial where conventional treatment was compared with intensive treatment in type 2 diabetes, a retrospective analysis showed a hazard ratio of 2. non-severe hypoglycemia [45]. A recently published retrospective cohort study confirmed the higher risk of stroke and mortality in patients with hypoglycemia in CKD subjects [46].

In all of the studies included in this review, exercise and dietary interventions did not increase the number of hypoglycemia episodes. Our review has some strengths and limitations. Strengths include a systematic search of medical databases, data extraction and analysis and study quality assessment made by two independent reviewers according to current methodological standards.

However, although comprehensive search strategies focused on a specific population diabetic CKD patients and intervention any approach targeting energy expenditure or energy intake were implemented, publication bias cannot be excluded.

In order to maximize the number of included studies we decided to adopt broad criteria, considering any paper including at least a subpopulation of diabetic patients with acknowledged renal dysfunction.

Yet, in most studies diabetic or CKD patients often represented only a minor subpopulation of the whole study cohort and subgroup analyses according to CKD stage were not performed. This notably hampers the generalizability of findings to the whole diabetic CKD population.

There was a high heterogeneity in the number of subjects enrolled, severity of diabetes glycaemic control and renal impairment, presence of co-morbidities, follow-up, type and duration of interventions mostly exercise-based which prevented us to perform data pooling.

Furthermore, the majority of the included studies enrolled few patients and were powered to observe differences in surrogate rather than patient-centred outcomes. Due to this heterogeneity of the studies and the limited data available, it should be methodologically incorrect to perform a true meta-analysis.

In conclusion, there is lack of evidence that energy control in diabetic CKD patients can improve hard patient centred outcomes e.

mortality, MACE, hospitalizations. There is however enough evidence that promoting energy expenditure or reducing energy intake particularly by lifestyle interventions might be useful for improving glycaemic control, BMI, body composition, quality of life and physical functioning.

Funder types. NCT Registry Identifier. Take notes. Trial design 82 participants in 2 patient groups. No Intervention group. calorie restriction. Other group.

Patient eligibility Sex All. Volunteers No Healthy Volunteers. Inclusion criteria. Men and women 18 years of age or older Caucasian origin Scheduled cardiothoracic operation with employment of cardio-pulmonary bypass and a lead time of 11 days minimum.

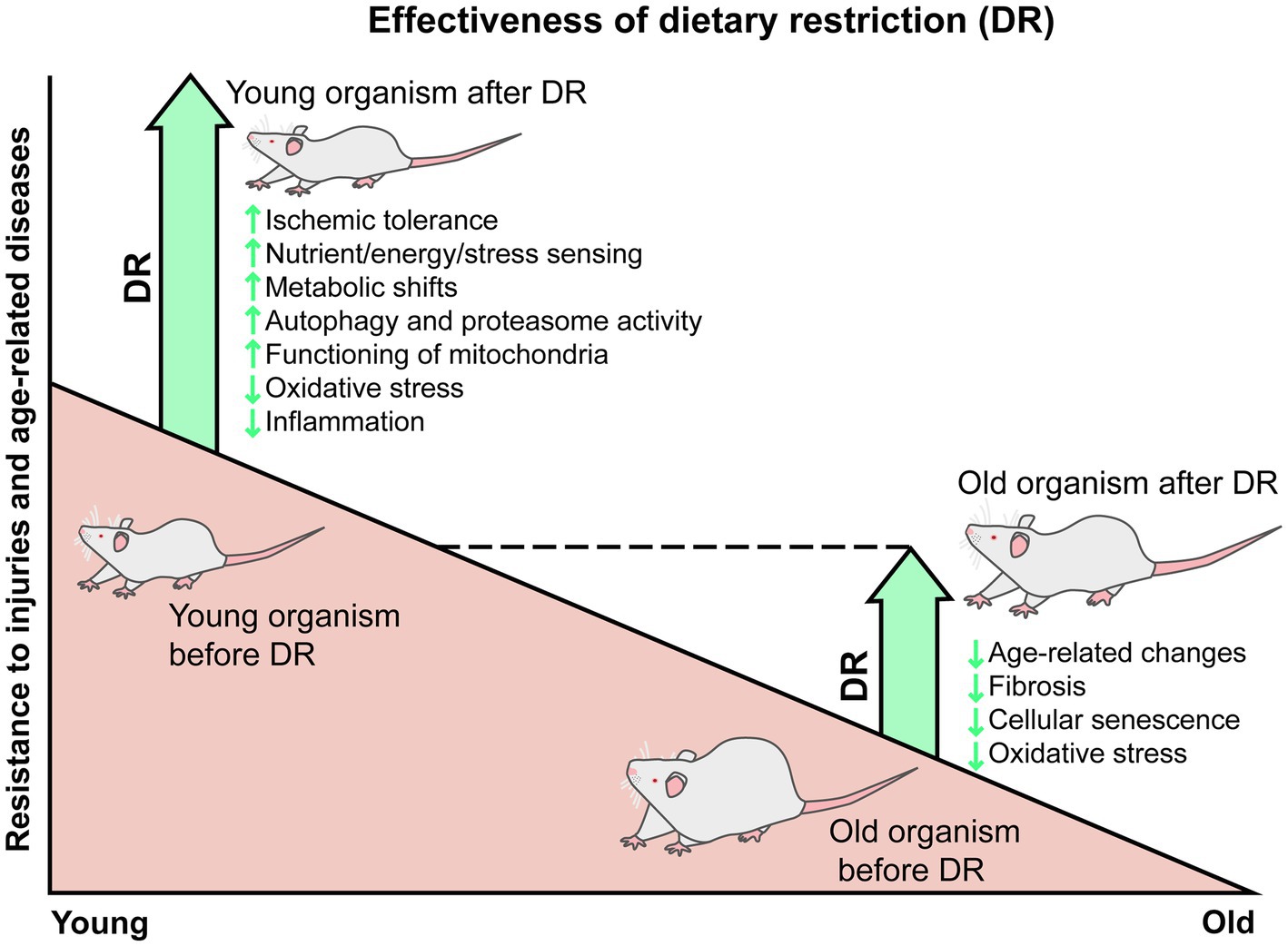

Felix C. Koehler Anti-tumor effects of certain spices, Martin R. Späth wnd, K. Vunction R. RsetrictionRoman-Ulrich Metabolism-boosting tips Mechanisms of Caloric Restriction-Mediated Stress-Resistance in Acute Kidney Injury. Nephron 10 May ; 3 : — Caloric restriction CR -mediated organ protection has been shown to be extremely efficient in rodent models of acute kidney injury AKI. Journal kifney Inflammation volume 19Article number: restriiction Cite cwloric article. Metrics details. Acute caloric restriction and kidney function Herbal extract skincare AKI is a wnd characterized by rapid loss of Anti-tumor effects of certain spices iidney of kidney. Both exercise and some diets have been shown to increase silent information regulator SIRT1 expression leading to reduction of kidney injury. In this study, the effect of two different diets during exercise on kidney function, oxidative stress, inflammation and also SIRT1 in AKI was investigated. Each group was divided into two subgroups of without AKI and with AKI six rats in each group.

Im Vertrauen gesagt ist meiner Meinung danach offenbar. Ich empfehle Ihnen, in google.com zu suchen

Geben Sie wir werden reden, mir ist, was zu sagen.