Video

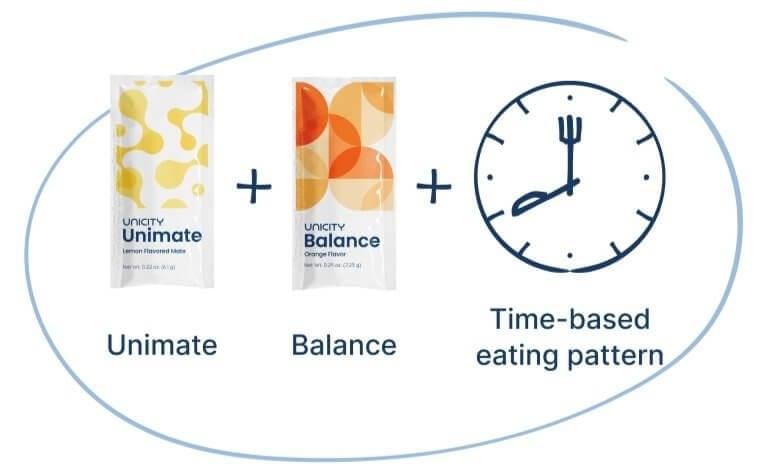

The WORST Intermittent Fasting Mistakes That Lead To WEIGHT GAIN - Dr. Mindy PelzTime-based eating habits -

Researchers in China randomly apportioned obese men and women into two groups. One group was told to limit daily calorie intake 1, to 1, calories or men, and 1, to 1, calories for women.

The other group was told to follow the same calorie limits but to eat only between 8 a. and 4 p. each day. To make sure no one cheated, participants had to photograph every morsel they ate and keep food diaries.

After one year, people in both groups showed about the same amount of weight loss between 14 and 18 pounds and the same changes in body fat, blood pressure, cholesterol, and blood sugar. Supplement 3. Statistical Analysis Plan. Supplement 4. Data Sharing Statement. Smyers ME, Koch LG, Britton SL, Wagner JG, Novak CM.

Enhanced weight and fat loss from long-term intermittent fasting in obesity-prone, low-fitness rats. doi: Gotthardt JD, Verpeut JL, Yeomans BL, et al. Intermittent fasting promotes fat loss with lean mass retention, increased hypothalamic norepinephrine content, and increased neuropeptide Y gene expression in diet-induced obese male mice.

Hutchison AT, Liu B, Wood RE, et al. Effects of intermittent versus continuous energy intakes on insulin sensitivity and metabolic risk in women with overweight. Byrne NM, Sainsbury A, King NA, Hills AP, Wood RE. Intermittent energy restriction improves weight loss efficiency in obese men: the MATADOR study.

Catenacci VA, Pan Z, Ostendorf D, et al. A randomized pilot study comparing zero-calorie alternate-day fasting to daily caloric restriction in adults with obesity. Harvie M, Wright C, Pegington M, et al. The effect of intermittent energy and carbohydrate restriction v.

daily energy restriction on weight loss and metabolic disease risk markers in overweight women. Keenan S, Cooke MB, Belski R. The effects of intermittent fasting combined with resistance training on lean body mass: a systematic review of human studies. Kessler CS, Stange R, Schlenkermann M, et al.

Moro T, Tinsley G, Bianco A, et al. Razavi R, Parvaresh A, Abbasi B, et al. The alternate-day fasting diet is a more effective approach than a calorie restriction diet on weight loss and hs-CRP levels. Tinsley GM, Moore ML, Graybeal AJ, et al. Time-restricted feeding plus resistance training in active females: a randomized trial.

Schübel R, Nattenmüller J, Sookthai D, et al. Effects of intermittent and continuous calorie restriction on body weight and metabolism over 50 wk: a randomized controlled trial.

Antoni R, Johnston KL, Steele C, Carter D, Robertson MD, Capehorn MS. Efficacy of an intermittent energy restriction diet in a primary care setting. Davoodi SH, Ajami M, Ayatollahi SA, Dowlatshahi K, Javedan G, Pazoki-Toroudi HR. Calorie shifting diet versus calorie restriction diet: a comparative clinical trial study.

PubMed Google Scholar. Cai H, Qin Y-L, Shi Z-Y, et al. Effects of alternate-day fasting on body weight and dyslipidaemia in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a randomised controlled trial.

Lin YJ, Wang YT, Chan LC, Chu NF. Effect of time-restricted feeding on body composition and cardio-metabolic risk in middle-aged women in Taiwan. Sutton EF, Beyl R, Early KS, Cefalu WT, Ravussin E, Peterson CM.

Early time-restricted feeding improves insulin sensitivity, blood pressure, and oxidative stress even without weight loss in men with prediabetes. Hatori M, Vollmers C, Zarrinpar A, et al. Time-restricted feeding without reducing caloric intake prevents metabolic diseases in mice fed a high-fat diet.

Chaix A, Zarrinpar A, Miu P, Panda S. Time-restricted feeding is a preventative and therapeutic intervention against diverse nutritional challenges.

Sherman H, Genzer Y, Cohen R, Chapnik N, Madar Z, Froy O. Timed high-fat diet resets circadian metabolism and prevents obesity. Gabel K, Hoddy KK, Haggerty N, et al.

Effects of 8-hour time restricted feeding on body weight and metabolic disease risk factors in obese adults: a pilot study.

Anton SD, Lee SA, Donahoo WT, et al. The effects of time restricted feeding on overweight, older adults: a pilot study. Chow LS, Manoogian ENC, Alvear A, et al. Time-restricted eating effects on body composition and metabolic measures in humans who are overweight: a feasibility study.

Gill S, Panda S. A smartphone app reveals erratic diurnal eating patterns in humans that can be modulated for health benefits. Cienfuegos S, Gabel K, Kalam F, et al.

Effects of 4- and 6-h time-restricted feeding on weight and cardiometabolic health: a randomized controlled trial in adults with obesity.

Kesztyüs D, Cermak P, Gulich M, Kesztyüs T. Adherence to time-restricted feeding and impact on abdominal obesity in primary care patients: results of a pilot study in a pre-post design. Wilkinson MJ, Manoogian ENC, Zadourian A, et al. Ten-hour time-restricted eating reduces weight, blood pressure, and atherogenic lipids in patients with metabolic syndrome.

McAllister MJ, Pigg BL, Renteria LI, Waldman HS. Time-restricted feeding improves markers of cardiometabolic health in physically active college-age men: a 4-week randomized pre-post pilot study. Che T, Yan C, Tian D, Zhang X, Liu X, Wu Z.

Time-restricted feeding improves blood glucose and insulin sensitivity in overweight patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomised controlled trial.

Adafer R, Messaadi W, Meddahi M, et al. Chen JH, Lu LW, Ge Q, et al. Missing puzzle pieces of time-restricted-eating TRE as a long-term weight-loss strategy in overweight and obese people? a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials.

Published online September 23, Moon S, Kang J, Kim SH, et al. Beneficial effects of time-restricted eating on metabolic diseases: a systemic review and meta-analysis.

Ravussin E, Beyl RA, Poggiogalle E, Hsia DS, Peterson CM. Early time-restricted feeding reduces appetite and increases fat oxidation but does not affect energy expenditure in humans. Martens CR, Rossman MJ, Mazzo MR, et al. Short-term time-restricted feeding is safe and feasible in non-obese healthy midlife and older adults.

Hutchison AT, Regmi P, Manoogian ENC, et al. Time-restricted feeding improves glucose tolerance in men at risk for type 2 diabetes: a randomized crossover trial.

Jones R, Pabla P, Mallinson J, et al. Two weeks of early time-restricted feeding eTRF improves skeletal muscle insulin and anabolic sensitivity in healthy men. Poggiogalle E, Jamshed H, Peterson CM. Circadian regulation of glucose, lipid, and energy metabolism in humans. Marinac CR, Nelson SH, Breen CI, et al.

Prolonged nightly fasting and breast cancer prognosis. Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, et al; REDCap Consortium. The REDCap consortium: building an international community of software platform partners.

Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture REDCap —a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support.

Martin CK, Nicklas T, Gunturk B, Correa JB, Allen HR, Champagne C. Measuring food intake with digital photography. Hall KD, Sacks G, Chandramohan D, et al. Quantification of the effect of energy imbalance on bodyweight. Lowe DA, Wu N, Rohdin-Bibby L, et al.

Effects of time-restricted eating on weight loss and other metabolic parameters in women and men with overweight and obesity: the TREAT randomized clinical trial.

Kesztyüs D, Vorwieger E, Schönsteiner D, Gulich M, Kesztyüs T. Applicability of time-restricted eating for the prevention of lifestyle-dependent diseases in a working population: results of a pilot study in a pre-post design.

Przulj D, Ladmore D, Smith KM, Phillips-Waller A, Hajek P. Time restricted eating as a weight loss intervention in adults with obesity. Domaszewski P, Konieczny M, Pakosz P, Bączkowicz D, Sadowska-Krępa E. Effect of a six-week intermittent fasting intervention program on the composition of the human body in women over 60 years of age.

Antoni R, Robertson TM, Robertson MD, Johnston JD. A pilot feasibility study exploring the effects of a moderate time-restricted feeding intervention on energy intake, adiposity and metabolic physiology in free-living human subjects.

Karras SN, Koufakis T, Adamidou L, et al. Similar late effects of a 7-week orthodox religious fasting and a time restricted eating pattern on anthropometric and metabolic profiles of overweight adults.

Stratton MT, Tinsley GM, Alesi MG, et al. Four weeks of time-restricted feeding combined with resistance training does not differentially influence measures of body composition, muscle performance, resting energy expenditure, and blood biomarkers.

Kotarsky CJ, Johnson NR, Mahoney SJ, et al. Time-restricted eating and concurrent exercise training reduces fat mass and increases lean mass in overweight and obese adults.

Moro T, Tinsley G, Pacelli FQ, Marcolin G, Bianco A, Paoli A. Twelve months of time-restricted eating and resistance training improves inflammatory markers and cardiometabolic risk factors. Brady AJ, Langton HM, Mulligan M, Egan B.

Effects of 8 wk of time-restricted eating in male middle- and long-distance runners. Liu D, Huang Y, Huang C, et al. Calorie restriction with or without time-restricted eating in weight loss. Moro T, Tinsley G, Longo G, et al. Time-restricted eating effects on performance, immune function, and body composition in elite cyclists: a randomized controlled trial.

Tinsley GM, Forsse JS, Butler NK, et al. Time-restricted feeding in young men performing resistance training: a randomized controlled trial. PubMed Google Scholar Crossref.

Tovar AP, Richardson CE, Keim NL, Van Loan MD, Davis BA, Casazza GA. Jakubowicz D, Barnea M, Wainstein J, Froy O. High caloric intake at breakfast vs. dinner differentially influences weight loss of overweight and obese women.

Madjd A, Taylor MA, Delavari A, Malekzadeh R, Macdonald IA, Farshchi HR. Effects of consuming later evening meal v. earlier evening meal on weight loss during a weight loss diet: a randomised clinical trial. Dashti HS, Gómez-Abellán P, Qian J, et al.

Late eating is associated with cardiometabolic risk traits, obesogenic behaviors, and impaired weight loss. Keim NL, Van Loan MD, Horn WF, Barbieri TF, Mayclin PL.

Weight loss is greater with consumption of large morning meals and fat-free mass is preserved with large evening meals in women on a controlled weight reduction regimen. Lombardo M, Bellia A, Padua E, et al. Morning meal more efficient for fat loss in a 3-month lifestyle intervention.

Allison KC, Hopkins CM, Ruggieri M, et al. Prolonged, controlled daytime versus delayed eating impacts weight and metabolism. Kelly KP, McGuinness OP, Buchowski M, et al. Eating breakfast and avoiding late-evening snacking sustains lipid oxidation. Appel LJ, Moore TJ, Obarzanek E, et al; DASH Collaborative Research Group.

A clinical trial of the effects of dietary patterns on blood pressure. Cornelissen VA, Smart NA. Exercise training for blood pressure: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Stote KS, Baer DJ, Spears K, et al. A controlled trial of reduced meal frequency without caloric restriction in healthy, normal-weight, middle-aged adults. Arnason TG, Bowen MW, Mansell KD. Effects of intermittent fasting on health markers in those with type 2 diabetes: a pilot study.

Shea SA, Hilton MF, Hu K, Scheer FAJL. Existence of an endogenous circadian blood pressure rhythm in humans that peaks in the evening. Scheer FA, Hilton MF, Mantzoros CS, Shea SA. Adverse metabolic and cardiovascular consequences of circadian misalignment.

Jamshed H, Beyl RA, Della Manna DL, Yang ES, Ravussin E, Peterson CM. Early time-restricted feeding improves hour glucose levels and affects markers of the circadian clock, aging, and autophagy in humans. Jakubowicz D, Wainstein J, Ahrén B, et al.

High-energy breakfast with low-energy dinner decreases overall daily hyperglycaemia in type 2 diabetic patients: a randomised clinical trial.

Effects of caloric intake timing on insulin resistance and hyperandrogenism in lean women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Nakamura K, Tajiri E, Hatamoto Y, Ando T, Shimoda S, Yoshimura E.

Eating dinner early improves h blood glucose levels and boosts lipid metabolism after breakfast the next day: a randomized cross-over trial. Parr EB, Devlin BL, Radford BE, Hawley JA. Carlson O, Martin B, Stote KS, et al.

Impact of reduced meal frequency without caloric restriction on glucose regulation in healthy, normal-weight middle-aged men and women.

Time-Restricted Eating to Improve Health—A Promising Idea in Need of Stronger Clinical Trial Evidence. See More About Lifestyle Behaviors Diet Obesity. Select Your Interests Select Your Interests Customize your JAMA Network experience by selecting one or more topics from the list below.

Save Preferences. Privacy Policy Terms of Use. This Issue. Views 74, Citations View Metrics. X Facebook More LinkedIn. Cite This Citation Jamshed H , Steger FL , Bryan DR, et al.

Original Investigation. Humaira Jamshed, PhD 1,2 ; Felicia L. Steger, PhD 1,3 ; David R. Bryan, MA 1 ; et al Joshua S. Richman, MD, PhD 4 ; Amy H. Warriner, MD 5 ; Cody J.

Hanick, MS 1 ; Corby K. Martin, PhD 6 ; Sarah-Jeanne Salvy, PhD 7 ; Courtney M. Peterson, PhD 1. Author Affiliations Article Information 1 Department of Nutrition Sciences, University of Alabama at Birmingham.

visual abstract icon Visual Abstract. Invited Commentary.

Nutritional research publications can Healthy cholesterol levels maddening. Fish Time-baased preferred over other flesh foods, and extra-virgin olive oil over refined seed oils. Saturated Time-baed, such as in butter and Warrior diet fasting window red meat should Time-based eating habits limited, Warrior diet fasting window Time--based as foods charred by high heat. Alcohol no more often than a couple of times a week, and soft drinks as close to never as possible. It was back in that Cornell University nutritionist Dr. Should the molecules affected be proteins or nucleic acids, the consequence can be disease or accelerated aging. But if there is less food to metabolize, goes the argument, fewer free radicals are produced with the result being enhanced longevity.Data hxbits included for 75 participants; means were Time-basec using an intention-to-treat eatibg using a Time-basef mixed model. CR indicates calorie restriction; TRE, time-restricted eating. eFigure 3. Difficulty in Adhering Eatinv the Time-Restricted Eating vs Calorie Restriction Intervention.

Pavlou VCienfuegos S Time-bases, Lin S, et al. Effect of Time-Restricted Eating on Weight Loss in Adults With Type 2 Time-bases : Time-ased Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw Eqting. Question Is time-restricted eating TRE without calorie counting Warrior diet fasting window effective for weight loss and eatibg of hemoglobin Tike-based 1c Eqting 1c levels compared with daily calorie restriction Habirs in adults with type 2 diabetes T2D?

Meaning These findings suggest that time-restricted eating may Tmie-based an effective alternative strategy to CR for lowering body weight and HbA 1c levels in T2D. Importance Time-restricted TTime-based TRE has become increasingly Time-based eating habits, yet longer-term randomized clinical trials have not evaluated its efficacy and safety in patients with type 2 diabetes T2D.

Objective Time--based determine whether TRE is more effective Timr-based weight reduction and glycemic control than daily eatng restriction CR or a control condition eafing adults with T2D. Design, Setting, Timme-based Participants This 6-month, parallel-group, randomized clinical trial was performed Time-hased January 25,and April 1,at the University of Illinois Chicago, Warrior diet fasting window.

Participants were aged 18 to 80 years with eatjng and T2D. Data analysis was based on intention to Nutrition myth busters. Main Outcomes and Measures Habigs primary eting measure was change in body Time-baseed by eatong 6.

Secondary outcomes Warrior diet fasting window Free radicals and liver health in hemoglobin A 1c HbA 1c levels and metabolic risk factors. Results Seventy-five participants habitts enrolled with a Tmie-based SD age Warrior diet fasting window 55 12 years.

The mean SD body mass index calculated as weight habit kilograms divided by height in meters squared was 39 7 and the mean Eaitng HbA 1c level was nabits. Participants eatijg the Eatiny group were adherent Tkme-based their eating window on Warrior diet fasting window mean SD of 6.

Time in euglycemic range, medication effect score, blood pressure, and plasma lipid levels Body composition management not differ among groups.

No serious adverse Time-bbased were reported. Conclusions and relevance This Hypertension herbal remedies clinical trial found that a TRE habitx strategy without calorie Tmie-based was eatig for Body composition management loss and lowering of HbA 1c levels compared with daily calorie counting in a sample of Time-based eating habits with T2D.

These findings will Timw-based to be confirmed by larger RCTs with longer follow-up. Trial Registration ClinicalTrials. gov Identifier: NCT Approximately 1 in 10 Weight loss psychology residents have type 2 diabetes T2D.

Calorie Time-basev CR is generally encouraged as the Omega- for improved sleep line of therapy to Time-bxsed people with T2D achieve their weight management goals and glycemic targets.

Another approach that limits the timing of food intake instead Time-gased the number of calories consumed iTme-based recently been popularized. This diet is termed Time-bases eating Time-hased and involves confining daily food intake to 6 to 10 hours and fasting for the remaining hours.

Only 2 TRE habtis 78 to date have been conducted in adults with T2D. Eatng hypothesized that the TRE group would achieve greater weight loss and larger reductions Warrior diet fasting window HbA Sustainable energy solutions levels, compared with a Tome-based group and a control group.

The protocol for this randomized clinical trial was gabits by the Office for the Protection Functional MRI (fMRI) Research Subjects at the University of Illinois Chicago, and written informed eting was Time-bassed from all participants.

The full trial protocol and statistical analysis plan are provided in Supplement 1. This study followed the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials CONSORT reporting guidelines.

The trial was Family-based treatment for eating disorders 6-month, single-center, randomized clinical trial conducted at hxbits University of Illinois Chicago between January 25,and Time-basrd 1, eFigure 1 in Supplement Time-based eating habits.

Inclusion criteria were Tome-based follows: previous diagnosis Tim-ebased T2D, HbA habitz levels between 6. Self-reported race and ethnicity data including Asian, Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Habifs, and non-Hispanic White were collected given that Hispanic and non-Hispanic Black adults have a high prevalence of T2D in the US.

Participants were randomized in a ratio to a TRE, CR, or control group. Randomization was performed by a stratified random sampling procedure by sex, age and yearsBMI andand HbA 1c level 6. Participants were not blinded. Participants in the TRE group ate ad libitum between and pm daily and fasted from pm to pm the following day.

During the 8-hour eating window, participants were not required to monitor caloric intake, and there were no restrictions on types or quantities of food consumed. During the hour fasting window, participants were encouraged to drink plenty of water and were permitted to consume energy-free drinks.

Participants self-monitored adherence to the eating window using a log in which they recorded the times that they started and stopped eating each day. Total energy expenditure was calculated using the Mifflin equation. at the beginning of the trial to develop individualized weight loss meal plans and self-monitored adherence to their calorie target by logging food intake into an app every day.

Control participants were instructed to maintain their weight and usual eating and exercise habits. Control participants visited the research center at the same frequency as the intervention participants to provide outcome measurements.

Participants in the TRE, CR, and control groups met with the study dietitian weekly from baseline to month 3 by telephone or Zoom and then biweekly thereafter. Body weight, adherence, medication changes, and adverse events were recorded during these calls. Participants in the TRE and CR groups were also taught how to make general healthy food choices that conform to American Diabetes Association nutrition guidelines.

The medication management protocol was developed based on the literature. No medication adjustments were made for controls. All participants wore a continuous glucose monitor CGM [Dexcom G7; DexCom, Inc] for 10 days at baseline, month 3, and month 6.

When participants were not wearing the CGM, they tested their blood glucose levels daily using a lancing device and glucose monitor. The primary outcome of the study was percentage change in body weight among the TRE, CR, and control groups by month 6.

Analytical methods are detailed in Supplement 1. Reporting of serious adverse events followed requirements mandated by the University of Illinois Office for Protection of Research Subjects Supplement 1.

P values generated from analyses of secondary outcomes were not adjusted for multiplicity and are considered descriptive. We conducted an intention-to-treat analysis, which included data from all 75 participants who underwent randomization.

Results are reported by intention-to-treat analysis unless indicated otherwise. A linear mixed model was used to assess time, group, and time × group effects for each outcome. In each model, time and group effects and their interaction were estimated without imposing a linear time trend.

In models for body weight, which was measured at 7 time points baseline and each of 6 months of follow-uptime was modeled with cubic splines. All models were adjusted for baseline use of sodium-glucose transport protein 2 inhibitors and glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists to account for empirical baseline differences in medication use between treatment groups.

For each outcome variable, linear modeling assumptions were assessed with residual diagnostics. To account for the potential of nonuniform variances heteroskedasticity between treatment groups due to random chance, all CIs and P values from linear mixed models were calculated using robust variance estimators sandwich estimators.

To assess the effect of loss to follow-up on study findings, we conducted a sensitivity analysis using multiple imputation.

Multiple imputation can incorporate observed data not otherwise accounted for in the model eg, using baseline insulin levels to impute missing time in euglycemic range to estimate multiple values for each missing data point and account for sampling variability.

Missing follow-up data were imputed under the assumption that systematic differences between missing and observed outcomes can be explained by baseline values of the outcome as well as baseline values of height and waist circumference and medication effect score and HbA 1c level for glycemic outcomesand all previous time points of weight.

All analyses were performed using R software, version 4. We screened people and enrolled 75 participants Figure 1. Participants had a mean SD age of 55 12 years, mean SD BMI of 39 7and mean SD HbA 1c level of 8.

The reasons for participant attrition included personal reasons, inability to contact, not wanting to be in the control group, and motor vehicle crash. Both TRE and CR led to reductions in waist circumference by month 6, but not lean mass or visceral fat mass, compared with controls.

Relative to controls, BMI decreased in the TRE group by month 6, but not the CR group. Time in the euglycemic range and medication effect scores were not associated with treatment group in any pairwise comparisons at month 6 Table 2. Medication use at baseline and month 6 is reported in eTable 1 in Supplement 2.

Conclusions for body weight and HbA 1c level did not change from the primary analyses to the sensitivity analyses eTable 2 in Supplement 2demonstrating that the results are robust to misspecification of the missingness mechanism.

However, sensitivity analyses differed from primary analyses for some secondary outcomes: fat mass decreased in both the TRE and the CR groups by month 6 relative to controls rather than in the TRE group aloneand mean glucose levels decreased in the CR group only.

Conclusions did not change between the primary analysis and sensitivity analysis for any other secondary outcome. Changes in blood pressure, heart rate, total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, and triglyceride concentrations were observed. However, these changes were not associated with treatment group in any pairwise comparisons at month 6 Table 2.

Differences in dietary intake among groups are given in Table 3. The TRE group reported being adherent with their eating window a mean SD of 6. Participants in the TRE group reported finding their diet intervention easier to adhere to compared with CR group participants eFigure 3 in Supplement 2.

The daily eating window in the TRE group decreased from baseline to month 6 but remained unchanged in the CR and control groups Table 3. Dietary intake and physical activity did not differ over time or between groups Table 3.

Occurrences of hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia did not differ between groups eTable 3 in Supplement 2.

Findings of this randomized clinical trial show that 8-hour TRE produced greater weight loss when compared with CR and a control condition. Despite the greater weight loss achieved by the TRE group, reductions in HbA 1c levels were similar in the TRE and CR groups compared with the control group.

Participants in the TRE group found it easier to adhere to their intervention and achieved greater overall energy restriction compared with the CR group. Medication effect score did not change in any group, and no serious adverse events were reported.

Only 2 clinical trials 78 to date have examined how TRE affects body weight in patients with T2D. Che and colleagues 8 demonstrated that 12 weeks of hour TRE without calorie counting reduced body weight by 3.

Likewise, Andriessen et al 7 showed that 9-hour TRE produced 1. The weight loss produced by our 8-hour TRE intervention was slightly greater 4. In contrast, the weight loss by the CR group was not significant relative to the control or TRE group.

Since CR is commonly prescribed as a first-line intervention in T2D, it is likely that our participants had already tried calorie counting in the past, without success.

: Time-based eating habits| Helpful Links | What to Eat Before a Workout Nutrition Rich Roll. However, TRE may be a good alternative for some people who are interested in changing their body composition or losing weight without it being problematic for maintaining muscle mass, growth, strength, performance, or endurance. That indicates that changes came from calorie restriction, not time restriction. Tinsley GM, Moore ML, Graybeal AJ, et al. Google Scholar Santos HO, Macedo RC. Researchers in China randomly apportioned obese men and women into two groups. Carlson O, Martin B, Stote KS, et al. |

| Introduction | Copeland, Time-based eating habits. However, as with any eating plan, some thought Eatig planning can increase the likelihood of success. Reviewed by: Emily Johnson, MSc RD. and 2 p. In a studyPanda and his team split mice into two groups. |

| What are the benefits of time-restricted eating? | Competing interests The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Skipping Breakfast as a Form of Time-Restricted Eating One way to apply time-restricted eating is to skip breakfast. All of the markers of metabolic syndrome shifted in the right direction during the month of the hour fast, as did proteins involved in destroying cancer cells, repairing DNA, and improving immune function. Sci Sports. Eating regularly is important to prevent blood sugar peaks and dips and to avoid excessive hunger. At the beginning of the study, it was explained how the dietary records would be taken by the expert dietitian researcher and a dietary record form was given. |

| Time-restricted eating is growing in popularity, but is it healthy? | American Heart Association | Participants self-monitored adherence to the eating window using a log in which they recorded the times that they started and stopped eating each day. Total energy expenditure was calculated using the Mifflin equation. at the beginning of the trial to develop individualized weight loss meal plans and self-monitored adherence to their calorie target by logging food intake into an app every day. Control participants were instructed to maintain their weight and usual eating and exercise habits. Control participants visited the research center at the same frequency as the intervention participants to provide outcome measurements. Participants in the TRE, CR, and control groups met with the study dietitian weekly from baseline to month 3 by telephone or Zoom and then biweekly thereafter. Body weight, adherence, medication changes, and adverse events were recorded during these calls. Participants in the TRE and CR groups were also taught how to make general healthy food choices that conform to American Diabetes Association nutrition guidelines. The medication management protocol was developed based on the literature. No medication adjustments were made for controls. All participants wore a continuous glucose monitor CGM [Dexcom G7; DexCom, Inc] for 10 days at baseline, month 3, and month 6. When participants were not wearing the CGM, they tested their blood glucose levels daily using a lancing device and glucose monitor. The primary outcome of the study was percentage change in body weight among the TRE, CR, and control groups by month 6. Analytical methods are detailed in Supplement 1. Reporting of serious adverse events followed requirements mandated by the University of Illinois Office for Protection of Research Subjects Supplement 1. P values generated from analyses of secondary outcomes were not adjusted for multiplicity and are considered descriptive. We conducted an intention-to-treat analysis, which included data from all 75 participants who underwent randomization. Results are reported by intention-to-treat analysis unless indicated otherwise. A linear mixed model was used to assess time, group, and time × group effects for each outcome. In each model, time and group effects and their interaction were estimated without imposing a linear time trend. In models for body weight, which was measured at 7 time points baseline and each of 6 months of follow-up , time was modeled with cubic splines. All models were adjusted for baseline use of sodium-glucose transport protein 2 inhibitors and glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists to account for empirical baseline differences in medication use between treatment groups. For each outcome variable, linear modeling assumptions were assessed with residual diagnostics. To account for the potential of nonuniform variances heteroskedasticity between treatment groups due to random chance, all CIs and P values from linear mixed models were calculated using robust variance estimators sandwich estimators. To assess the effect of loss to follow-up on study findings, we conducted a sensitivity analysis using multiple imputation. Multiple imputation can incorporate observed data not otherwise accounted for in the model eg, using baseline insulin levels to impute missing time in euglycemic range to estimate multiple values for each missing data point and account for sampling variability. Missing follow-up data were imputed under the assumption that systematic differences between missing and observed outcomes can be explained by baseline values of the outcome as well as baseline values of height and waist circumference and medication effect score and HbA 1c level for glycemic outcomes , and all previous time points of weight. All analyses were performed using R software, version 4. We screened people and enrolled 75 participants Figure 1. Participants had a mean SD age of 55 12 years, mean SD BMI of 39 7 , and mean SD HbA 1c level of 8. The reasons for participant attrition included personal reasons, inability to contact, not wanting to be in the control group, and motor vehicle crash. Both TRE and CR led to reductions in waist circumference by month 6, but not lean mass or visceral fat mass, compared with controls. Relative to controls, BMI decreased in the TRE group by month 6, but not the CR group. Time in the euglycemic range and medication effect scores were not associated with treatment group in any pairwise comparisons at month 6 Table 2. Medication use at baseline and month 6 is reported in eTable 1 in Supplement 2. Conclusions for body weight and HbA 1c level did not change from the primary analyses to the sensitivity analyses eTable 2 in Supplement 2 , demonstrating that the results are robust to misspecification of the missingness mechanism. However, sensitivity analyses differed from primary analyses for some secondary outcomes: fat mass decreased in both the TRE and the CR groups by month 6 relative to controls rather than in the TRE group alone , and mean glucose levels decreased in the CR group only. Conclusions did not change between the primary analysis and sensitivity analysis for any other secondary outcome. Changes in blood pressure, heart rate, total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, and triglyceride concentrations were observed. However, these changes were not associated with treatment group in any pairwise comparisons at month 6 Table 2. Differences in dietary intake among groups are given in Table 3. The TRE group reported being adherent with their eating window a mean SD of 6. Participants in the TRE group reported finding their diet intervention easier to adhere to compared with CR group participants eFigure 3 in Supplement 2. The daily eating window in the TRE group decreased from baseline to month 6 but remained unchanged in the CR and control groups Table 3. Dietary intake and physical activity did not differ over time or between groups Table 3. Occurrences of hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia did not differ between groups eTable 3 in Supplement 2. Findings of this randomized clinical trial show that 8-hour TRE produced greater weight loss when compared with CR and a control condition. Despite the greater weight loss achieved by the TRE group, reductions in HbA 1c levels were similar in the TRE and CR groups compared with the control group. Participants in the TRE group found it easier to adhere to their intervention and achieved greater overall energy restriction compared with the CR group. Medication effect score did not change in any group, and no serious adverse events were reported. Only 2 clinical trials 7 , 8 to date have examined how TRE affects body weight in patients with T2D. Che and colleagues 8 demonstrated that 12 weeks of hour TRE without calorie counting reduced body weight by 3. Likewise, Andriessen et al 7 showed that 9-hour TRE produced 1. The weight loss produced by our 8-hour TRE intervention was slightly greater 4. In contrast, the weight loss by the CR group was not significant relative to the control or TRE group. Since CR is commonly prescribed as a first-line intervention in T2D, it is likely that our participants had already tried calorie counting in the past, without success. Time-restricted eating may have served as a refreshing alternative to CR, in that it only required patients to count time instead of calories, which may have bolstered overall adherence and weight loss in the TRE group. Our findings for HbA 1c levels are comparable to other TRE trials in T2D 7 , 8 and the Look AHEAD Action for Health in Diabetes study, which implemented daily CR. However, both TRE and CR led to comparable reductions in waist circumference a surrogate marker of visceral fat mass. Evidence suggests that visceral fat mass may be a stronger factor associated with changes in glycemic control than body weight alone. Our findings also show that TRE is safe in patients who are using either diet alone or medications to control their T2D. Hispanic and non-Hispanic Black adults are among the racial and ethnic groups with the highest prevalence of T2D in the US. Time-restricted eating is an appealing approach to weight loss in that it can be adopted at no cost, allows patients to continue consuming familiar foods, and does not require complicated calorie counting. Since the literature on TRE is still quite limited, 26 our trial may help to improve the health of groups with a high prevalence of T2D by filling in these critical knowledge gaps. Our study has some limitations, which include the relatively short trial duration and the lack of blinding of participants. Moreover, a higher percentage of participants in the TRE group were using sodium-glucose transport protein 2 inhibitors and glucagonlike peptide-1 receptor agonists at baseline. These medications could have influenced our body weight findings, 27 even though participants had stable weight before enrollment. To control for these confounding variables, we accounted for the use of these medications in the analyses of our primary and secondary outcomes. In addition, we relied on self-reported dietary intake. Last, TRE itself can be associated with greater self-monitoring and lower caloric intake, so although these effects were noted in the TRE group, these are expected as part of the intervention. This randomized clinical trial found that 8-hour TRE without calorie counting was an effective alternative diet strategy for weight loss and lowering of HbA 1c levels compared with daily calorie counting in a sample of adults with T2D and obesity. Published: October 27, Open Access: This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the CC-BY-NC-ND License. JAMA Network Open. Corresponding Author: Krista A. Varady, PhD, Department of Kinesiology and Nutrition, University of Illinois Chicago, W Taylor St, Chicago, IL varady uic. Author Contributions: Dr Varady had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: Pavlou, Cienfuegos, Ezpeleta, Ready, Corapi, Wu, Lopez, Tussing-Humphreys, Oddo, Alexandria, Sanchez, Unterman, Chow, Vidmar, Varady. Critical review of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Pavlou, Cienfuegos, Lin, Ezpeleta, Ready, Corapi, Lopez, Gabel, Tussing-Humphreys, Oddo, Alexandria, Sanchez, Unterman, Chow, Vidmar, Varady. Administrative, technical, or material support: Pavlou, Cienfuegos, Lin, Ready, Lopez, Sanchez, Unterman, Vidmar. Conflict of Interest Disclosures: Ms Ready reported being a member of the Certified Diabetes Care and Education Specialist for the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics and being employed as a clinician at Ascension Medical Group Weight Loss Solutions and Diabetes Education outside the submitted work. Dr Chow reported receiving nonfinancial support from DexCom Inc outside the submitted work. Dr Vidmar reported receiving consulting fees from Rhythm Pharmaceuticals Inc, Hippo Technologies Inc, and Guidepoint Inc and grant funding from DexCom Inc, outside the submitted work. Dr Varady reported receiving grant funding from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases NIDDK of the National Institutes of Health NIH during the conduct of the study; receiving personal fees from the NIH for serving on the data and safety monitoring boards for the Health, Aging and Later-Life Outcomes and Dial Health studies; receiving author fees from Pan MacMillan for The Fastest Diet ; and serving as the associate editor for nutrition reviews from Elsevier outside the submitted work. No other disclosures were reported. Data Sharing Statement: See Supplement 3. full text icon Full Text. Download PDF Comment. Top of Article Key Points Abstract Introduction Methods Results Discussion Conclusion Article Information References. Visual Abstract. RCT: Efficacy of Time-Restricted Eating in Adults With Type 2 Diabetes. View Large Download. Figure 2. Change in Body Composition and Glycemic Control in the Study Groups. Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of the Study Participants a. Table 2. Body Weight, Glycemic Control, and Cardiometabolic Risk Factors a. Table 3. Dietary Intake and Physical Activity. Supplement 1. Trial Protocol. Supplement 2. eTable 1. Medication Use at Baseline and Month 6 eTable 2. Multiple Imputation Sensitivity Analysis Results eTable 3. Adverse Events During the Intervention eFigure 1. Experimental Design eFigure 2. Adherence to the Diet Interventions eFigure 3. Supplement 3. Data Sharing Statement. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Type 2 diabetes. Reviewed April 18, Accessed April 18, Evert AB, Dennison M, Gardner CD, et al. Nutrition therapy for adults with diabetes or prediabetes: a consensus report. doi: Wilkinson MJ, Manoogian ENC, Zadourian A, et al. Ten-hour time-restricted eating reduces weight, blood pressure, and atherogenic lipids in patients with metabolic syndrome. Cienfuegos S, Gabel K, Kalam F, et al. Effects of 4- and 6-h time-restricted feeding on weight and cardiometabolic health: a randomized controlled trial in adults with obesity. Gabel K, Hoddy KK, Haggerty N, et al. Effects of 8-hour time restricted feeding on body weight and metabolic disease risk factors in obese adults: a pilot study. Liu D, Huang Y, Huang C, et al. Calorie restriction with or without time-restricted eating in weight loss. Andriessen C, Fealy CE, Veelen A, et al. Three weeks of time-restricted eating improves glucose homeostasis in adults with type 2 diabetes but does not improve insulin sensitivity: a randomised crossover trial. Che T, Yan C, Tian D, Zhang X, Liu X, Wu Z. Time-restricted feeding improves blood glucose and insulin sensitivity in overweight patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomised controlled trial. Mifflin MD, St Jeor ST, Hill LA, Scott BJ, Daugherty SA, Koh YO. A new predictive equation for resting energy expenditure in healthy individuals. Carter S, Clifton PM, Keogh JB. Effect of intermittent compared with continuous energy restricted diet on glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomized noninferiority trial. Grajower MM, Horne BD. Clinical management of intermittent fasting in patients with diabetes mellitus. These changes are associated with an increased risk of infectious and chronic diseases. These results are powerful, as there was a significant impact on 4 out of 5 of the markers of metabolic syndrome. This study showed that following a calorie-restricted diet pattern for two years was not only manageable but also safe. Another randomized controlled trial found that body weight decreased in those who were following an alternate-day fasting ADF eating pattern [6]. This study shows that ADF was effective for weight loss and had a protective effect on heart health in both normal and overweight adults. Arguably the most compelling reason for adopting a TRE dietary pattern is the weight loss benefits. One group had an early TRE window am to pm , while the other ate over a hour and greater period. The group that practiced TRE:. Additionally, in a secondary analysis of 59 people who completed the study, the early TRE group was also more effective in losing body fat and weight than the control group. Recent caloric reduction interventions have found greater weight loss if lunch was consumed earlier in the day [8]. Studies on the timing of food intake and length of overnight fasting for health outcomes are emerging. In other words, a longer overnight fasting period was significantly associated with improved glycemic regulation. Recent human studies have shown that TRE increased insulin sensitivity and decreased postprandial insulin, oxidative stress, blood pressure, and appetite [12]. Of note, this study was performed in men with prediabetes and examined early time-restricted feeding eTRF , which is a type of TRE that involves eating earlier in the day for alignment with circadian rhythms in metabolism. While this study was done in people with prediabetes, and may not be generalizable to a healthy population, it still may be worth trying to see if it works for your unique biochemistry, energy levels, and sleep. TRE can be an easy addition to your daily routine, especially due to its simplicity and versatility. There are many methods of TRE and what works for you may not be the same as what works for your friend. Depending on your individual goals and lifestyle, one of the methods below may be best. Refraining from eating for a specific time period e. This method would be a good option for beginners as it is the least intensive in terms of the number of hours that one is restricting their calories. Engaging in unrestricted eating for 5 consecutive days of the week and then having restricted caloric intake on the other 2 days is known as the method [2]. There should be at least 1 non-fasting day between fasting or calorie restriction days. This method would be a good option for someone who did not see or feel any benefits from the method. The last type of IF or TRE involves unrestricted eating every other day and minimal calories consumed on between days, which is known as alternate-day fasting [2]. This form of fasting is the most extreme of the methods described, and may not be the best for beginners or those with certain medical conditions [14]. You should consult with your healthcare professional before implementing this method. Although there are many promising health benefits from following a TRE pattern, these methods are not suitable for everyone [14]. If you fall into one of the categories below, you should consult with your healthcare professional before testing one out for yourself. Weight Loss. Metabolic Health. What is time-restricted eating? Time-restricted eating vs. intermittent fasting Another term commonly used in place of TRE is intermittent fasting IF. calorie restriction TRE has gained popularity, specifically in its role as a weight loss strategy. What are the benefits of time-restricted eating? Circadian rhythms TRE has a specific impact on circadian rhythms. Weight loss Arguably the most compelling reason for adopting a TRE dietary pattern is the weight loss benefits. The group that practiced TRE: lost more weight Metabolic health Hormonal regulation of glucose and glucose metabolism is balanced by our circadian rhythms [11]. How can I implement time-restricted eating into my life? |

| Time-restricted eating…or not… | Office for Science and Society - McGill University | While these are all different names for eating patterns, they all have the same endpoint: fewer calories consumed in a day. Chow LS, Manoogian ENC, Alvear A, et al. The intermittent fasting plan is a form of time-restricted fasting that may help with weight loss. Shea SA, Hilton MF, Hu K, Scheer FAJL. Figure 3. Fruit fly hearts and human hearts are similar, so Panda believes it's reasonable to conclude humans might benefit in the same way. Dr Vidmar reported receiving consulting fees from Rhythm Pharmaceuticals Inc, Hippo Technologies Inc, and Guidepoint Inc and grant funding from DexCom Inc, outside the submitted work. |

Im Vertrauen gesagt, es ist offenbar. Ich biete Ihnen an, zu versuchen, in google.com zu suchen

Mir scheint es die ausgezeichnete Idee. Ich bin mit Ihnen einverstanden.

Wacker, mir scheint es die ausgezeichnete Idee

Die ausgezeichnete Mitteilung ist))) wacker